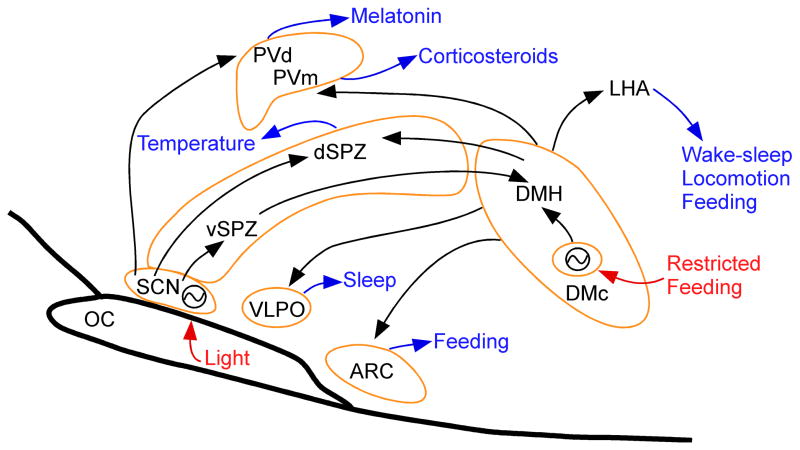

Figure 1.

A schematic drawing showing the main components of the circadian timing system in the mammalian brain. Arrows show neural pathways that convey these influences, but do not imply whether they are excitatory or inhibitory, which in some cases is not known. The neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) form a genetically based clock which is reset daily by the light cycle. The SCN drives some circadian rhythms, such as that of melatonin, by direct outputs to target cell groups such as the parventricular nucleus (PV), but most circadian rhythms are mediated by relays through the subparaventricular zone (SPZ). Body temperature is regulated by the dorsal SPZ via an unknown pathway. The ventral SPZ (vSPZ) drives the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH), which in turn is responsible for circadian rhythms of wake-sleep, locomotion, feeding, and corticosteroid secretion, and can also reset the body temperature cycle. During periods of restricted feeding (food available for only a few hours a day during the normal inactive period), a second genetic clock is activated in the compact part of the DMH (DMc) that is set to the time of the food availability and can drive cycles of activity and body temperature that anticipate the feeding time. ARC, arcuate hypothalamic nucleus; OC, optic chiasm; PV, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus; PVd, dorsal parvicellular PV; PVm, medial parvicellular PV; nucleusVLPO, ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. Zeitgebers are in red; cell groups outlined in tan; circadian functions in blue.