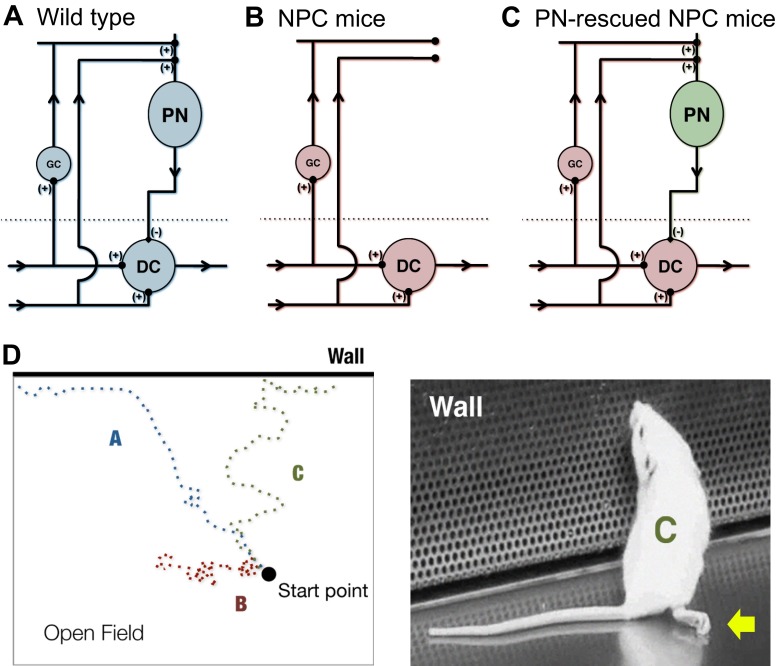

Fig. 3.

Genetic dissection of disease neural circuits and resulting behavioral modifications. The effects of restoring neuronal circuitry in NPC disease can be observed in a mouse model in which controlled neuron survival of discrete neuronal networks can be implemented. (A–C) Simplified circuit diagrams of the cerebellum for (A) wild-type mice, (B) NPC disease mice and (C) Purkinje neuron (PN)-rescued NPC disease mice. Compared with wild-type mice, in NPC disease mice, connectivity of PNs with granule neurons (GC) and deep cerebellar nuclei (DC) is lost, whereas PN connectivity in the cerebellar cortex is restored in PN-rescued mice (Lopez et al., 2011; Lopez et al., 2012a). (D) Even with continuous progression of severe phenotypes that affect ambulation, such as dystonia and hind limb paralysis (illustrated by arrow in right-hand mouse image), some beneficial improvements in mice activity can be observed with PN rescue (Lopez et al., 2011). Depicted here is a cartoon example of an open field test showing three tracks of mouse movement that correspond to the cerebellar conditions in panels A–C. The tracks show the difference in behavior between mice of advanced disease stages. A mouse corresponding to track B remains largely unresponsive to its environment and immobile. In comparison, a mouse corresponding to track C exhibits severe movement defects but is able to escape the open field and investigate its surroundings, similar to the wild-type mouse represented by track A.