Abstract

Objective: Due its inhibitory effects on chemical carcinogenesis and inflammation, Cucurbitacins have been proposed as an effective agent for the prevention or treatment of human cancers. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of Cucurbitacin E (CuE) on human breast cancer cells. Methods: The inhibitory effect of CuE on proliferation of Bcap37 and MDA-MB-231 cells was assessed by MTT assay. The cell cycle distribution and cell apoptosis were determined by flow cytometry (FCM). The expression of pro-caspase 3, cleaved caspase 3, p21, p27 and the phosphorylation of signaling proteins was detected by Western Blotting. Results: CuE inhibited the growth of human breast cancer cells in a dose and time-dependent manner. FCM analysis showed that CuE induced G2/M phase arrest and cell apoptosis. CuE treatment promoted the cleavage of caspase 3 and upregulated p21 and p27. In addition, the phosphorylation of STAT3 but not ERK-1/2 was abrogated upon CuE treatment. Interestingly, losedose CuE significantly enhanced the growth inhibition induced by cisplatin. Conclusions Cucurbitacin E (CuE) could inhibit the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro. CuE induced both apoptosis and cell cycle arrest probably through the inhibition of STAT3 function. Lose-dose CuE significantly enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells, further indicating the potential clinical values of CuE for the prevention or treatment of human breast cancer

Keywords: Cucurbitacin E, breast cancer, apoptosis

Introduction

Although female breast cancer incidence rate began decreasing in the America, breast cancer is still the most common cancer among women worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer death in women, exceeded only by lung cancer. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), there are 232,340 cases diagnosed and 39,620 cases of patients die from breast cancer every year (www.cancer.org). Death rates from breast cancer have been declining since about 1989, mainly resulting from the earlier detection through screening and increased awareness. However, there are still more patients were diagnosed as invasive or advanced breast cancer which request intensive treatments and is associated with poor outcomes. Treatments of breast cancers include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, most commonly used chemotherapy drugs lack specificity toward tumor cells and the clinical efficacy of chemotherapy was limited by side-effects, toxicity and drug resistance. Therefore, there has been a growing interest in the use of herbs as a promising source of more efficient new therapeutic anticancer drugs. In addition, natural compounds for prevention of initiation and progression of human cancers was proposed as a valuable source for the chemoprevention of human cancers.

Cucurbitacin is a group of tetracyclic triterpenes derived from plants [1]. It has been long time ago that Cucurbitacin was found to have some medicinal properties such as the inhibition of chemical carcinogenesis and inflammation. Therefore, it was proposed as a promising source to develop novel drugs for the prevention and treatment of various cancers. Cucurbitacins contain at least five cucurbitacin compounds, named Cucurbitacin B (CuB), Cucurbitacin D (CuD), Cucurbitacin E (CuE), Cucurbitacin I (CuI), and Cucurbitacin Q (CuQ). Among them, CuB and CuE were widely studied. Cucurbitacin E (CuE, α-elaterin) is an active component from traditional Chinese medicine such as Cucubita pepo cv Dayangua [2]. It has been shown to have growth inhibitory effects in many cancers such as bladder cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer and leukemia [2-5]. However, the effect of CuE on breast cancer was rarely reported.

In this study, we found that CuE effectively inhibit the growth of two independent human breast cancer cell lines by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. In addition, CuE promoted the activation of capase-3, upregulated p21 and p27 expression and inhibited the activation of STAT3. Interestingly, CuE enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, chemicals and antibodies

Both Bcap-37 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were bought from cell bank (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. CuE was purchased from Shanghai Zhanshu Chemical Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Hoechst 3342 was from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China), propidium iodide (PI) and 3-(4, 5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Sigma, antibodies for GAPDH, Pro-caspase 3, Cleaved-caspase 3 and the secondary antibodies anti-rabbit were all from Cell Signaling Technology.

Cell viability assay

For the measurement of cell viability, the two human breast cancer cell lines were seeded into 96-well plates at 3000 cells per well (100 μl) and treated with either DMSO or various concentrations of CuE (0.1-100 μM). After the cells were incubated at 37°C for 24, 48 and 72 hours, MTT (15 μl; 5 mg/mL; Sigma) was added into each well. After 4 hours incubation, 150 μl DMSO was added to each well. The absorbance of the product was measured with an ELISA reader at 570 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

The two human breast cancer cell lines were seeded into 6-well plates at 4 × 105 cells per well and treated with either DMSO or various concentrations of CuE for 24 h. The cells were then collected and fixed in 70% methanol overnight at 4°C. The samples were stained with PI before analyzed by flow cytometry.

Assessment of apoptosis

The two human breast cancer cell lines were seeded into 6-well plates at 4 × 105 cells per well and treated with either DMSO or various concentrations of CuE for 24 h. Collected cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen) before analyzed by flow cytometry.

Western blotting

Cells (3 × 105/well) seeded into 6-well plates were treated with 10 μM, 100 μM CuE or DMSO. Cells were lyzed with lysis buffer containing PMSF and phosphatase inhibitors [6]. Protein concentration was determined by Nanodrop 2000. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were used to separate the protein. The blot was incubated with the primary antibodies, followed by secondary antibodies and detected by autoradiography using X-ray film after the incubation with ECL (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All values from the triplicated experiments were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). The SPSS 17.0 was used for statistical analysis. Oneway ANOVA was used to compare the difference between control and concentration treatments in each group. P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

CuE inhibited cell growth of breast cancer cells

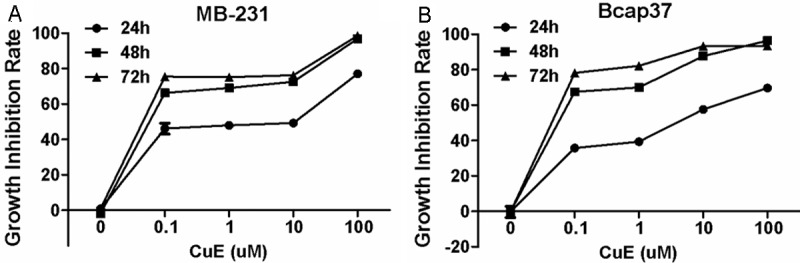

Breast cancer cells were treated with various concentrations (0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM) of CuE or DMSO as a control for 24, 48 and 72 hours. MTT method was then used to determine the viable cells. Our data indicated that CuE inhibited cell growth in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (ANOVA analysis, p < 0.05, Figure 1A and 1B). After the treatment with 0.1 μM CuE for 24 h, the growth of Bcap37 and MB-231 cells were significantly inhibited. At concentration of 100 μM, most of cancer cells detached from the dish.

Figure 1.

CuE inhibited the growth of breast cancer cells. After the incubation with various concentrations of CuE for different times, the viability of MB-231 (A) and Bcap37 (B) cells was determined by MTT assay.

CuE induces the apoptosis of breast cancer cells

In consistence to the results of MTT, the Annexin V-FITC/PI assay results confirmed the induction of Bcap37 and MB-231 by CuE (Figure 2A and 2B). Cells undergo apoptosis after the incubation of 1 μM CuE for 12 hours and more apoptotic cells were detected with higher concentration of CuE or longer incubation time.

Figure 2.

CuE induced the apoptosis of breast cancer cells. After the incubation with various concentrations of CuE for different times, the apoptosis of MB-231 (A) and Bcap37 (B) cells stained with FITC-Annexin VI and PI was determined by flowcytometry.

CuE induces cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells

In addition to apoptosis activation, CuE can also induce the cell cycle arrest in both breast cancer cell lines (Figure 3A and 3B). After CuE treatment, cells in S-phase were greatly reduced. More cells were blocked in G2-m phase, indicating that CuE can induce G2-M arrest in breast cancer cells.

Figure 3.

CuE induced cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells. After the incubation with various concentrations of CuE for different times, the cell cycle distribution of MB-231 (A) and Bcap37 (B) cells stained with PI was determined by flowcytometry.

Effect of CuE on oncogenic signaling in breast cancer cells

To understand the molecular mechanism of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest induced by CuE treatment, we also explored the effect of CuE on the expression of proteins related with apoptosis, cell cycle regulation and oncogenic signaling in breast cancer cells. In consistence with flowcytometry analysis, CuE treatment induced the cleavage of caspase-3 and the upregulation of p27 and p21 (Figure 4A). In addition, the phosphorylation of STAT3 was inhibited while the phosphorylation of ERK was not affected (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of CuE on the expression of cell cycle regulators and signaling proteins. A: The expression of caspase-3, p21 and p27 in Bcap37 and MB-231 cells were explored by western blotting analysis. B: The phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK (ERK-1/2) were explored by western blotting analysis.

CuE increased the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to cisplatin

Next, we wonder whether CuE can influence of effect of commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs for breast cancer cell. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B. Cisplatin can inhibit the growth of both breast cancer cell lines. The addition of low-dose (1 μM) Cue can further enhance the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells (Figure 5A and 5B). However, high-dose CuE (10 μM) has no such an effect.

Figure 5.

CuE enhanced growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin. The effect of low-dose (1 μM) and high-dose (10 μM) CuE on cisplatin-induced growth inhibition in MB-231 (A) and Bcap-37 (B) cells were determined by MTT assay.

Discussion

Cucurbitacin, a tetracyclic triterpenes compound from Cucurbitaceae, has been shown to inhibit chemical carcinogeneses and inflammation, thus being proposed as effective agents for the prevention or treatment of human cancers. Among different cucurbitacins, Cucur- bitacin E and B were widely studied. In the present study, we found Cucurbitacin E could inhibit the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro. CuE can induce both apoptosis and cell cycle arrest probably through the inhibition of STAT3 function. Interestingly, lose-dose CuE could significantly enhance the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells, further indicating the potential clinical values of CuE for the prevention or treatment of human breast cancer.

Up to date, more than 40 new cucurbitacins and cucurbitacin-derived compounds have been isolated from the cucurbitaceae family and other species of the plant Kingdome [7]. Many of them were found to be able induce cell apoptosis and growth inhibition. The most predominant mechanism for the apoptosis-inducing effect of cucurbitacins are their ability to modify mitochondrial trans-membrane potential and regulate the expression of genes related with apoptosis. In general, cucurbitacins are considered to be selective inhibitors of the JAK/STAT pathways [1,8,9]. In the next studies, it would be important to understand the molecular mechanism of the CuE-induced STAT3 inactivation. In addition, other mechanisms such as the MAPK pathway known to be important for cancer cell proliferation and survival may also be implicated in their apoptotic effects. However, in the present study, we found only STAT3 signaling but not MAPK pathway was impaired in breast cancer cells treated with CuE. Nevertheless, CuI can inhibit Rac1 activation in breast cancer cells independent of the Jak2 pathway [10], indicating the presence of other mechanisms for the tumor suppressive function of cucurbitacins. For example, CuD inhibited proliferation and induce apoptosis of T-cell leukemia cells by inducing the accumulation of inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) and suppressing NF-κB function [11].

In addition to promote the cleavage and activation of pro-caspase-3, CuE can also promote the expression of p21 and p27. This is consistent with previous report that CuB can upregulate the expression of p21 and p27 in breast cancer cells [12]. However, this effect of CuB is significant only in breast cancer cells with defective BRCA1 function [12]. In contrast, we found that CuE can significantly upregulate p21 and p27 expression and induce growth inhibition in breast cancer cells with effective BRCA1, indicating that CuE might be a superior drug candidate for breast cancer.

Cucurbitacins can also affect the cytoskeleton structure of actin and vimentin [13-16]. Importantly, this effect is not limited to cancer cells. Cucurbitacins also disrupted the F-actin and tubulin microfilaments cytoskeleton and reduced the motility of normal mitogen-induced T-lymphocytes and endothelial cells [17]. Although this function indicates anti-angiogenesis and anti-metastasis role of cucurbitacins, it also imply that cucurbitacins may have severe side effects in the clinical application for anti-cancer treatment. Chemical modifications are needed to improve its clinical efficacy by reducing potential side-effects.

Interestingly, lose-dose CuE could significantly enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells, further indicating the potential clinical values of CuE for the prevention and treatment of human breast cancer. It has been reported that cucurbitacins indeed have synergistic effects when used with standard chemotherapeutic drugs like doxorubicin and docetaxel [18,19]. In addition, some cucurbitacins including CuE promoted TRAIL-induced apoptosis [20]. This synergistic effect seems to be associated with the short but not long exposure of cucurbitacin. Similarly, we found low-dose but not high-dose CuE enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin. Moreover, low-dose of CuD synergistically potentiated the antiproliferative effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitor VPA [11].

In summary, we found CuE inhibited the growth of human breast cancer cells by inducing both apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. CuE inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT3 but not ERK-1/2. Lose-dose CuE significantly enhanced the growth inhibitory effect of cisplatin on breast cancer cells, further indicating the potential clinical application of CuE for the prevention and treatment of human breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LR12H16001), Qianjiang Scholarship of Zhejiang Province (2011R10061; 2011R10073) and Key Projects of Department of Science and Technology in Zhejiang Province (2012C13019-1).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Chen JC, Chiu MH, Nie RL, Cordell GA, Qiu SX. Cucurbitacins and cucurbitane glycosides: structures and biological activities. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:386–399. doi: 10.1039/b418841c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Lu B, Zhang X, Zhang J, Lai L, Li D, Wu Y, Song Y, Luo J, Pang X, Yi Z, Liu M. Cucurbitacin E, a tetracyclic triterpenes compound from Chinese medicine, inhibits tumor angiogenesis through VEGFR2-mediated Jak2-STAT3 signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2097–2104. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayyad SE, Abdel-Lateff A, Alarif WM, Patacchioli FR, Badria FA, Ezmirly ST. In vitro and in vivo study of cucurbitacins-type triterpene glucoside from Citrullus colocynthis growing in Saudi Arabia against hepatocellular carcinoma. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;33:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun C, Zhang M, Shan X, Zhou X, Yang J, Wang Y, Li-Ling J, Deng Y. Inhibitory effect of cucurbitacin E on pancreatic cancer cells growth via STAT3 signaling. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:603–610. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0698-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He Y, Korboukh I, Jin J, Huang J. Targeting protein lysine methylation and demethylation in cancers. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2012;44:70–79. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Ding L, Wang X, Zhang J, Han W, Feng L, Sun J, Jin H, Wang XJ. Pterostilbene simultaneously induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and cyto-protective autophagy in breast cancer cells. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alghasham AA. Cucurbitacins - a promising target for cancer therapy. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2013;7:77–89. doi: 10.12816/0006025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun J, Blaskovich MA, Jove R, Livingston SK, Coppola D, Sebti SM. Cucurbitacin Q: a selective STAT3 activation inhibitor with potent antitumor activity. Oncogene. 2005;24:3236–3245. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoennissen NH, Iwanski GB, Doan NB, Okamoto R, Lin P, Abbassi S, Song JH, Yin D, Toh M, Xie WD, Said JW, Koeffler HP. Cucurbitacin B induces apoptosis by inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway and potentiates antiproliferative effects of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5876–5884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Haber C, Kazanietz MG. Cucurbitacin I inhibits Rac1 activation in breast cancer cells by a reactive oxygen species-mediated mechanism and independently of Janus tyrosine kinase 2 and P-Rex1. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:1141–1154. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.084293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding N, Yamashita U, Matsuoka H, Sugiura T, Tsukada J, Noguchi J, Yoshida Y. Apoptosis induction through proteasome inhibitory activity of cucurbitacin D in human T-cell leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:2735–2746. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Promkan M, Dakeng S, Chakrabarty S, Bogler O, Patmasiriwat P. The effectiveness of cucurbitacin B in BRCA1 defective breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan KL, Duncan MD, Alley MC, Sausville EA. Cucurbitacin E-induced disruption of the actin and vimentin cytoskeleton in prostate carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1553–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00557-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren S, Ouyang DY, Saltis M, Xu LH, Zha QB, Cai JY, He XH. Anti-proliferative effect of 23,24-dihydrocucurbitacin F on human prostate cancer cells through induction of actin aggregation and cofilin-actin rod formation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1921-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Bao J, Guo J, Ding Q, Lu J, Huang M, Wang Y. Biological activities and potential molecular targets of cucurbitacins: a focus on cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:777–787. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283541384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin D, Wakimoto N, Xing H, Lu D, Huynh T, Wang X, Black KL, Koeffler HP. Cucurbitacin B markedly inhibits growth and rapidly affects the cytoskeleton in glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1364–1375. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smit HF, van den Berg AJ, Kroes BH, Beukelman CJ, Quarles van Ufford HC, van Dijk H, Labadie RP. Inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation by cucurbitacins from Picrorhiza scrophulariaeflora. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1300–1302. doi: 10.1021/np990215q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadzuka Y, Hatakeyama H, Sonobe T. Enhancement of doxorubicin concentration in the M5076 ovarian sarcoma cells by cucurbitacin E co-treatment. Int J Pharm. 2010;383:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T, Zhang M, Zhang H, Sun C, Yang X, Deng Y, Ji W. Combined antitumor activity of cucurbitacin B and docetaxel in laryngeal cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;587:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrich CJ, Thomas CL, Brooks AD, Booth NL, Lowery EM, Pompei RJ, McMahon JB, Sayers TJ. Effects of cucurbitacins on cell morphology are associated with sensitization of renal carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2012;17:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0652-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]