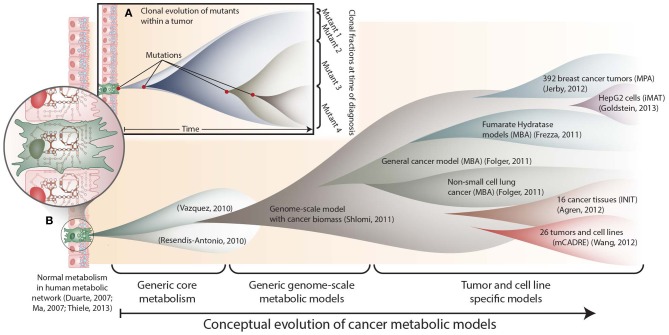

Figure 1.

The conceptual evolution of constraint-based models of cancer metabolism. (A) Clonal evolution commonly occurs in a developing tumor as new mutations are acquired that confer increased growth capabilities to new mutants. At the time of diagnosis, a tumor often consists of a mixed population of cancerous cells. (B) Similarly, the scope and specificity of cancer metabolic models have rapidly evolved over the past few years. Genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions have provided a valuable resource, since they contain thousands of known human metabolic reactions (Duarte et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2007; Thiele et al., 2013). This knowledge enabled the first two cancer-specific metabolic models, which focused on core metabolic pathways(Resendis-Antonio et al., 2010; Vazquez et al., 2010). In 2011, the first genome scale model of general cancer metabolism was used to provide insights into the Warburg effect(Shlomi et al., 2011). Shortly thereafter, transcriptomic data from the NCI-60 cell lines were used to build a general genome-scale model of cancer metabolism, which was used to assess metabolic drug targets(Folger et al., 2011). Now, numerous additional models have been built using data from specific cell lines and tumors. These models have elucidated pathways that differ between tumors(Agren et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012), identified pathways that are differentially regulated with changes in estrogen receptor or p53 expression(Jerby et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2013), and predicted potential anti-cancer drug targets(Folger et al., 2011; Frezza et al., 2011b).