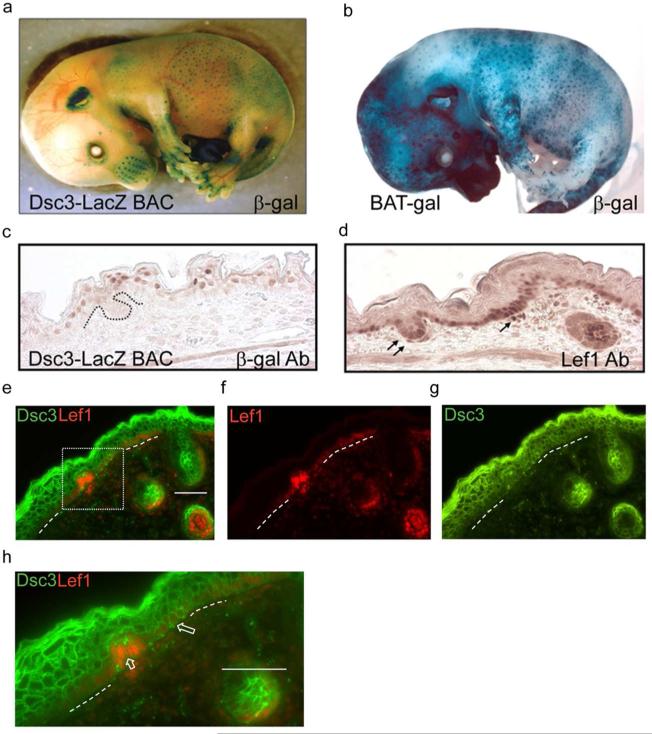

Figure 4. Wnt activity and Dsc3 expression during mouse appendage development.

(a). Whole mount in-situ staining for beta-galactosidase (β-gal) activity of a transgenic mouse (Dsc3-LacZ BAC, E15.5) expressing β-gal under the control of the Dsc3 promoter. Note that whisker pads, hair follicles and mammary glands (not shown) are strongly stained. (b) Whole mount β-gal staining of a BAT-gal transgenic mouse (Maretto et al., 2003) at E15.5. Note the similar staining patterns of the transgenic mice shown in a. and b. (c.) Immunohistochemistry staining of a skin section from a Dsc3-LacZ BAC mouse at E15.5 with (c) β-gal antibodies and (d) Lef-1 antibodies. The LacZ transgene contains a nuclear localization signal. Note that β-gal and Lef-1 expression appears to be mutually exclusive. Arrows point to Lef-1 expressing cells in a placode and a dermal papilla of a forming hair follicle. (e-g) Immunofluorescence staining of a developing hair follicle in wild type mouse skin at E16.5 with antibodies against Lef-1 and DSC3. The area demarcated by the dotted box is shown at higher magnification in panel (h). (h) The large arrow points to DSC3 positive keratinocytes in the basal cell layer. The short arrow points to DSC3-negative and Lef-1-positive cells in a forming hair placode. Dotted lines in (e-h), basement membrane area._Bar, 50μm