Abstract

A 7-year-old girl presented with an asymptomatic right supraclavicular swelling. Radiographs were interpreted as showing a non-union of her clavicle. No treatment was given at this time. However, she represented 12 years later with right upper limb pain and altered sensation. Examination revealed a positive Allen's test on the right. Repeat radiographs demonstrated a pseudarthrosis of the clavicle, associated with a secondary complication of thoracic outlet syndrome with vascular and neurological complications present. Non-operative management failed to relieve her symptoms. Operative intervention successfully treated her symptoms.

Background

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle (CPC) is a rare congenital condition. It has an undefined aetiology but it is distinct from craniocleidodysostosis (CCD), obstetric fractures and neurofibromatosis. Accompanying thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is rare and can be associated with significant vascular and neurological complications. This case report places an emphasis on the indications for surgery and the complications that can be associated with non-operative management of a clavicular pseudarthrosis.

Case presentation

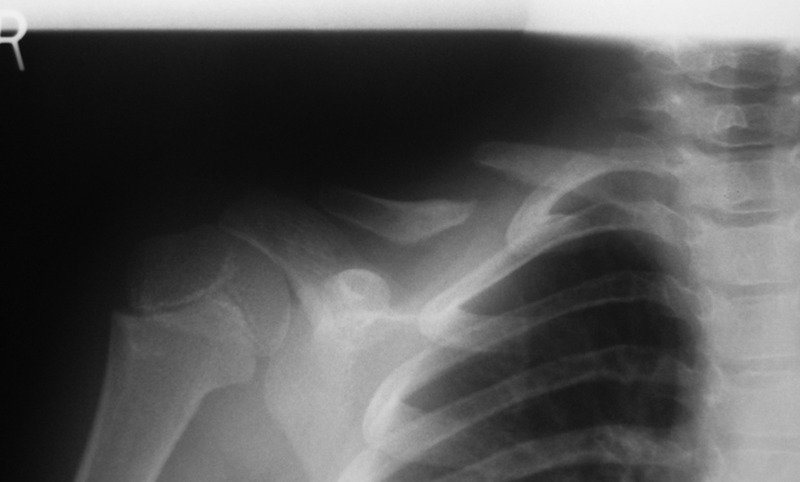

A 7-year-old Caucasian girl presented after her parents noticed a right supraclavicular swelling. The patient was asymptomatic of the swelling. There was no history of trauma and no definitive timeline as to when the lump was first noticed. The patient had an unaffected identical twin sister and she was born by elective caesarean section with no birth trauma reported. Her medical history consisted of a previous febrile convulsion, astigmatism and an episode of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. On examination, there was normal function of the right shoulder with no restriction of power or movement. A radiograph (figure 1) at this time was reported as showing a ‘hypertrophic non-union of the clavicle of which the lateral component formed the bony lump in the right supraclavicular fossa’. At this stage, she was asymptomatic so a decision was made not to treat and no further follow-up was arranged.

Figure 1.

Radiograph demonstrating a right clavicular pseudarthrosis, age 7.

The patient re-presented 12 years later at the age of 19 with pain and neurovascular symptoms affecting the right upper limb. The pain led to a restricted range of movement of the right shoulder with associated shooting pains radiating down the right arm. The patient experienced tingling and numbness of the right hand on elevation above shoulder level. Also, the right hand was objectively cooler compared with the left. The patient was unable to carry out her job adequately as a healthcare assistant. On examination, there was a prominent tender swelling over the mid-clavicular region (figure 2) with drooping of the right shoulder; however, the scapula level and spinal alignment were within the normal limits. No scoliosis was present. There was no tenderness over the shoulder joint or scapula. Allen's test was positive with reproduction of the patient's symptoms, namely, tingling and numbness of the right upper limb, alongside a reduced radial pulse volume. Neurological examination of the right upper limb suggested altered sensation in the C5, C6 dermatomes. There was reduced power in the right arm as compared with the left on shoulder abduction, elbow flexion and forearm supination. The patient was able to abduct the right arm but was unable to fully resist the examiner confirming four out of five abduction power. Abduction power was normal in the left arm. Muscle asymmetry of the upper limbs was observed with less muscle bulk on the right side. Normal tone and reflexes of the upper limbs was present. No other external congenital abnormalities were noted. No cervical ribs were present.

Figure 2.

Photographic anterior view of the right supraclavicular swelling, age 19.

Investigations

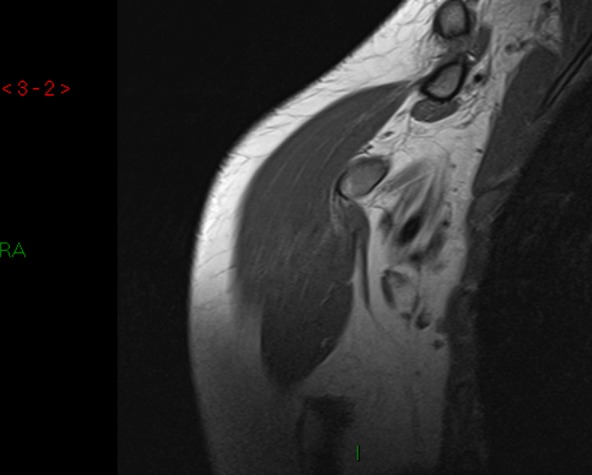

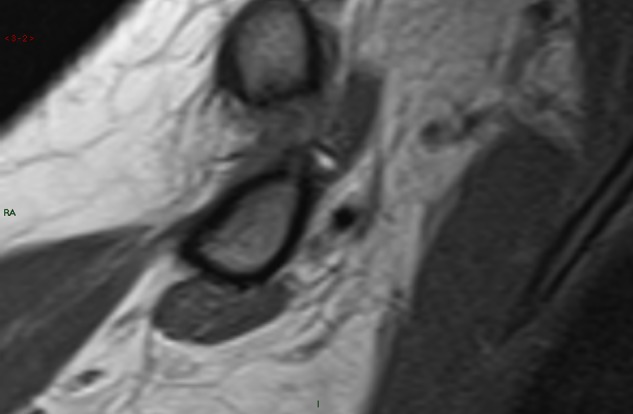

Follow-up radiographs were interpreted as showing a right clavicular pseudarthrosis (figure 3). A cervical spine radiograph was normal. MRI of the cervical spine and right shoulder confirmed the presence of a right clavicular pseudarthrosis with a fibrous connection of approximately 1 cm joining the ends of the pseudarthrosis. It confirmed a normal cervical spine and shoulder joint with intact rotator cuff muscles and long head of the biceps brachii. The MRI showed displacement of the suprascapular nerve and vessels posterior to the pseudarthrosis (figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Radiograph demonstrating a right clavicular pseudarthrosis, age 19.

Figure 4.

MRI demonstrating a right clavicular pseudarthrosis.

Figure 5.

Magnified view of MRI demonstrating a right clavicular pseudarthrosis.

Treatment

Conservative and operative management options were discussed with the patient. Conservative treatment was started. However, the patient was non-compliant and was discharged from physiotherapy within 2 months. Subsequently when she was reviewed in the clinic several months later, she was found to have no symptomatic improvement. Unfortunately, upon review, she was found to have increasing pain on movement and further occupational difficulties. It was decided that operative management would be most appropriate at this stage given the patient's neurovascular symptoms posed by TOS.

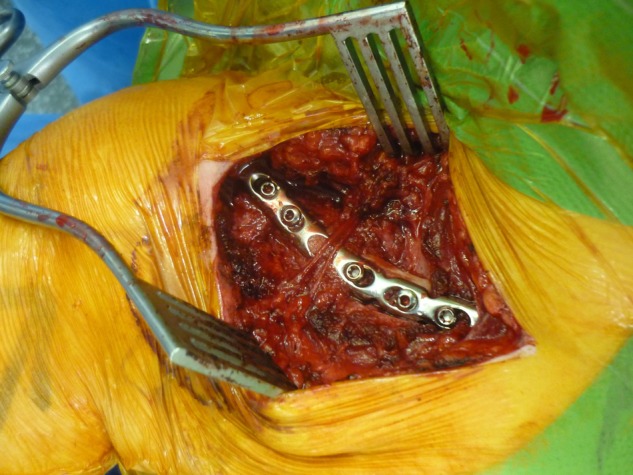

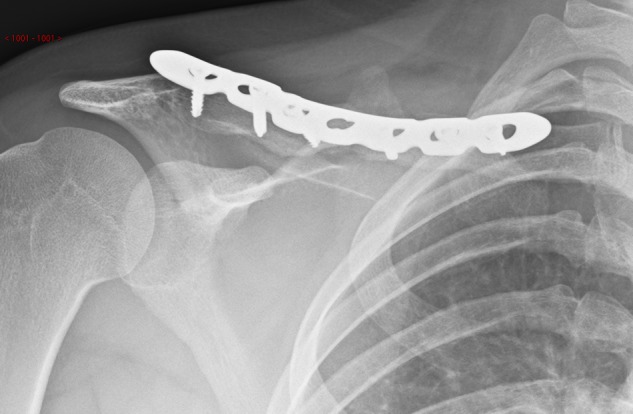

Surgery was carried out 12 years after the first presentation. The procedure (figures 6–8) consisted of the resection of the pseudarthrosis. A tricortical bone graft was taken from the right iliac crest and the defect site was grafted. A 7-hole clavicular locking plate was used to stabilise the osteotomy (figure 9).

Figure 6.

Following sharp and blunt dissection, demonstration of the location of the right-sided clavicular pseudarthrosis and identification of the supraclavicular nerve.

Figure 7.

Postresection of pseudarthrosis with iliac bone graft in situ.

Figure 8.

Right clavicle is stabilised with a 7-hole clavicular locking plate.

Figure 9.

Intraoperative radiograph demonstrating the 7-hole clavicular locking plate.

Outcome and follow-up

Follow-up was conducted at 2, 4 and 10 weeks postoperatively with radiographs taken on each occasion (figure 10). The patient's symptoms fully resolved postoperatively with complete functional recovery to match the contralateral limb with pain-free movements. Allen's, Roos, Adson and Wright's tests were all negative at follow-up. No vascular or neurological deformities were found on examination.

Figure 10.

Postoperative radiograph at 10 weeks.

Discussion

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle

Pseudarthrosis means ‘false joint’.1 The first case of CPC was documented in 1910.2 CPC is described as a clinical condition that is distinct from CCD, obstetric fractures and neurofibromatosis.2 3 There is a strong association of CPC with cervical ribs with its presence in around 15% of cases4; however, our case showed no evidence of a cervical rib. It is largely documented as being a right-sided condition3–15 with left-sided cases usually associated with dextrocardia.10 16 It is more commonly documented in women.13 17 18 However, one case series reported that men and women are equally affected.14

Gibson et al8 reported the first cases of bilateral pseudarthrosis. In these cases there was a strong familial predisposition, suggesting that genetics may play a role in the development of CPC. Several modes of inheritance have been suggested, from autosomal dominant8 to autosomal recessive.5 11 However, our case seems to dispute a purely genetic causal relationship, in that only one sister out of identical twins was affected with no other immediate family member having CPC. An autosomal dominant pattern would require one parent to always be affected and this is not supported by the literature.

It has also been suggested that CPC is due to abnormal intrauterine development. In utero, the positioning of the fetus in the left occiput anterior position may force pressure of the right shoulder against the pubic bones.13 However, no evidence has linked proven cases of CPC to in utero fetal positioning. Moreover, it has been suggested that environmental factors may play a strong role in CPC.

Embryologically, there has been discrepancy over whether the clavicles develop from one or two ossification centres. Historically, Gibson proposed that one ossification centre was normal and that if two were present in CPC then this would be an added abnormality.8 Conversely, more modern research points to the presence of two ossification sites, due to the finding of a growth plate on the sternal and acromial ends of the disjointed clavicle. Therefore, suggesting that CPC is due to abnormal fusion from two ossification sites in utero.19

It is agreed that CPC is atraumatic.3–6 8 9 13–16 18 20–22 The literature largely suggests that birth-associated clavicular fractures heal rapidly with no residual deformity8 suggesting that CPC is a distinct entity.

Thoracic outlet syndrome

TOS in itself is rare, however, it is particularly rare in the context of CPC and even more so in adolescents.

TOS demonstrates a wide spectrum of symptoms related to the degree and site of compression. It can affect the vascular structures of the subclavian artery and vein, alongside the peripheral and sympathetic nerves in the area. Any combination of these neurovascular structures can be affected by TOS. In the presented case, arterial TOS is described, with an element of neurogenic TOS due to nerve compression related to C5 and C6 dermatomes of the brachial plexus. The relationship of the subclavian artery and the CPC can account for the complication of TOS, in that the artery lies directly inferior to the medial end of the lateral component of the clavicle.10 Neurogenic TOS comprises 95% of the cases of TOS,23 making our case of arterial TOS in relation to CPC particularly unusual.

TOS in an adult with CPC has been described in the literature before. The patient had been asymptomatic of her CPC throughout childhood but a traumatic injury to the shoulder sparked the symptoms of TOS. Resection of the pseudarthrosis and the midportion of her clavicle relieved her symptoms.24 Our case shows originality in that the progression of TOS symptoms was unrelated to a traumatic event but simply due to the anatomical progression of the CPC. So although the majority of CPC cases remain asymptomatic throughout life, we have shown that some of the cohort will develop complicated issues surrounding the CPC that may require operative intervention.15 22 24

Complications of TOS can be divided into vascular and neurological outcomes. Symptoms and physical findings, include:

Arterial:

Venous:

Thrombotic or non-thrombotic obstruction

Oedema

Dusky discolouration

Cyanosis

Mild paraesthesia

Headaches23

Neurological:

Brachial plexus compression

Paraesthesia

Weakness26

Conservative vs. operative management

Indications for surgery include:

Symptomatic patients, for example, pain

Prevention of neurovascular damage, for example, TOS

Functional impairment

Cosmetic appearance

Some authors suggest that conservative management is adequate as patients on the whole do not have disturbed function on the affected side and that operative complications outweigh the potential benefits.7 27 They argue that it is a benign condition that should be treated as such. However, we have found that functional impairment can be disabling for those affected by CPC and following failed conservative treatment operative intervention may improve the functional outcome. It has been suggested that surgery provides the best results when carried out between the ages of 2–4 years. These children appear to show the best consolidation postoperatively. For children over 8 years of age, bone grafting becomes an essential component of any operative management. Prior to this age bone grafting is optional.18 Surgery prior to reaching 2 years of age has been performed but there is a fear of bone splintering,8 hence it has been suggested that surgery should be carried out no earlier than children of preschool age. Surgery in childhood helps to ensure ‘symmetrical growth of the shoulder girdle’.2,8 Some case reports have suggested that surgical treatment with an external fixator produces a better cosmesis postoperatively with minimal scarring and avoidance of a second surgical procedure to remove implants.6 However, there are multiple options available surgically for the treatment of CPC.

Surgical options include excision of the pseudarthrosis plus:

Internal fixation (plates and screws,29 screws alone29), Kirschner wires,8 12 14 15 intramedullary Steinmann pins4

External fixation

Complications of surgery include:

Infection

Implant failure

Delayed or non-union requiring reoperation

Splintering of the bone if the operation is performed at an early age8

Brachial plexus injury4

Vascular injury

Shoulder girdle asymmetry14

However, what results can be expected in adults who present with CPC? There are few case reports in the literature documenting CPC in late adolescence and adulthood. One such report documents the successful conservative management of a 45-year-old man who works as an Ear, Nose and Throat Surgeon who was left with a mild cosmetic swelling in the right midclavicular region and no functional impairment.27 This shows that conservative management may be appropriate in some patients if there are no concerning features and the cosmetic burden can be accepted. However, our case demonstrates that unaffected children can become symptomatic adults in relation to their CPC.

Conclusion

The historic acceptance that CPC is a benign condition should be altered in light of the development of TOS related to the condition. We add to the literature that pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is congenital, atraumatic, commonly on the right side and more frequently found in women. We dispute a purely genetic causation. We propose that the risk of TOS should be taken into consideration when posed with the dilemma of conservative vs operative management. Operative management can restore anatomical normality and may prevent the development of this complication.

Learning points.

Women may be more commonly affected.

Right-sided lesions are more common.

Atraumatic, congenital lesion.

No evidence added for a genetic component.

It is not always simply a cosmetic deformity.

Operative management should be considered in childhood.

Operative management is indicated with associated thoracic outlet syndrome.

Missed or delayed diagnosis is a concern.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the case report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Al-Hadidy A, Haroun A, Al-Ryalat N, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis associated with venous malformation. Skeletal Radiol 2007;2013:S15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzwilliams DCL. Hereditary cranio-cleido-dysostosis. Lancet 1910;2013:1466–75 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alldred AJ. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1963;2013:312–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toledo LC, MacEwen GD. Severe complication of surgical treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979;2013:64–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behringer BR, Wilson FC. Congenital pseuarthrosis of the clavicle. Am J Dis Child 1972;2013:511–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beslikas TA, Dadoukis DJ, Gigis IP, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2007;2013:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cataldo F. A 7-month old child with a clavicular swelling since birth. Eur J Pediatr 1999;2013:1001–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson DA, Carroll N. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;2013:629–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grogan DP, Love SM, Guidera KJ, et al. Operative treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. J Pediatr Orthop 1991;2013:176–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd-Roberts GC, Apley AG, Owen R. Reflections upon the aetiology of congenital pseudarthrosis of clavicle with a note on cranio-cleido dysostosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1975;2013:24–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manashil G, Lauffer S. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a report of three cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1979;2013:678–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molto FJL, Lluch DJB, Garrido IM. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a proposal for early surgical treatment. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;2013:689–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen R. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970; 2013:644–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persiani P, Molayem I, Villani C, et al. Surgical treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a report on 17 cases. Acta Orthop Belg 2008;2013:161–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sales de Gauzy J, Baunin C, Puget C, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle and thoracic outlet syndrome in adolescence. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;2013:299–301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakkers RJ, Tjin a Ton E, Bos CF. Left-sided congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicula. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;2013:45–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Currarino G, Herring J. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. Pediatr Radiol 2009;2013:1343–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figueiredo MJPSS, Braga SR, Akkari M, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: updating article. Rev Bras Ortop 2012;2013:21–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Brouchet A, Sales de Gauzy J, Accadbled F, et al. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a histopathological study in five patients. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;2013:399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price BD, Price CT. Familial congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: case report and literature review. Iowa Orthop J 1996;2013:153–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinlan WR, Brady PG, Regan BF. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. Acta Orthop Scand 1980;2013:489–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young MC, Richards RR, Hudson AR. Thoracic outlet syndrome with pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: treatment by brachial plexus decompression. Can J Surg 1988;2013:131–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders RJ, Hammond SL, Rao NM. Thoracic outlet syndrome a review. Neurologist 2008;2013:365–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bargar WL, Marcus RE, Ittleman FP. Late thoracic outlet syndrome secondary to pseudarthrosis of the clavicle. J Trauma 1984;2013:857–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roos DB. Thoracic outlet syndrome is underdiagnosed. Muscle Nerve 1999;2013:126–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murovic JA, Kim DH, Kim SH, et al. Thoracic outlet syndrome: part I. A review of the recent literature. Neurosurg Q 2007;2013:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalom A, Khermosh O, Wientroub S. The natural history of congenital pseuadarthrosis of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994;2013:846–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnall SB, King JD, Marrero G. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle: a review of the literature and surgical results of six cases. J Pediatr Orthop 1988;2013:316–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandran P, George H, James LA. Congenital clavicular pseudarthrosis: a comparison of the two treatment methods. J Child Orthop 2011;2013:1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]