Background: ATF6α recruits Mediator to activate endoplasmic reticulum stress response genes.

Results: Mediator subunit MED25 contains an ATF6α binding site.

Conclusion: The ATF6α-MED25 interaction contributes to Mediator recruitment to genes.

Significance: Learning how DNA binding transcription activators recruit coactivators to genes is important for understanding gene regulatory mechanisms.

Keywords: Coactivator Transcription, Coregulator Transcription, Gene Regulation, RNA Polymerase II, Transcription Factors

Abstract

Transcription factor ATF6α functions as a master regulator of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response genes. In response to ER stress, ATF6α translocates from its site of latency in the ER membrane to the nucleus, where it activates RNA polymerase II transcription of ER stress response genes upon binding sequence-specifically to ER stress response enhancer elements (ERSEs) in their promoter-regulatory regions. In a recent study, we demonstrated that ATF6α activates transcription of ER stress response genes by a mechanism involving recruitment to ERSEs of the multisubunit Mediator and several histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes, including Spt-Ada-Gcn5 (SAGA) and Ada-Two-A-containing (ATAC) (Sela, D., Chen, L., Martin-Brown, S., Washburn, M.P., Florens, L., Conaway, J.W., and Conaway, R.C. (2012) J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23035–23045). In this study, we extend our investigation of the mechanism by which ATF6α supports recruitment of Mediator to ER stress response genes. We present findings arguing that Mediator subunit MED25 plays a critical role in this process and identify a MED25 domain that serves as a docking site on Mediator for the ATF6α transcription activation domain.

Introduction

Response of human cells to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)3 stress involves activation of signaling pathways that are critical for cell survival and are implicated in diseases including diabetes, atherosclerosis, and neurodegeneration (1–3). A key player in the ER stress response is the basic leucine zipper transcription factor ATF6α. In unstressed cells, ATF6α is present in a latent form as a type II transmembrane protein in the ER. In response to ER stress, ATF6α is transported to the Golgi apparatus, processed by the S1P and S2P proteases (4–8), and then transported into the nucleus, where it binds sequence-specifically to ER stress response enhancer elements (ERSEs) in ER stress response genes and activates their transcription (4–9). Based on the observation that ectopic expression of the proteolytically processed form of ATF6α in unstressed cells is sufficient to activate transcription of most ER stress response genes, ATF6α is considered a master regulator of the ER stress response transcription program (4, 9–11).

In a recent study exploring the mechanism by which ATF6α activates RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcription of ER stress response genes (12), we obtained evidence that it functions at least in part by promoting recruitment to ERSEs of the multisubunit Mediator and several histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes, including SAGA and ATAC. Further dissection of the mechanism by which ATF6α recruits these Pol II coactivators to ER stress response genes revealed that the Mediator and HAT complexes bind to nonidentical but overlapping regions of the ATF6α transcription activation domain (AD). Furthermore, we discovered that the VP16 AD potently competes with ATF6α for binding to the Mediator, raising the possibility that the ATF6α and VP16 ADs might bind to the same or overlapping surfaces on Mediator. In light of previous studies demonstrating that the VP16 AD binds to the Mediator through its MED25 subunit (13–18), we initiated experiments to test the possibility that the ATF6α AD might also target Mediator through MED25. Below we present our findings, which identify MED25 as a docking site for transcription factor ATF6α on the multisubunit human Mediator complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Anti-MED18 (A300–777A), anti-MED1 (A300–793A), anti-MED14 (A301–044A), anti-MED15 (A302–422A), and anti-GST (A190–123A) antibodies were purchased from Bethyl. Anti-MED23 (550429) antibody was obtained from BD Pharmingen. Anti-MED25 (ARP50698 P050) antibody was from Aviva Systems Biology. Anti-FLAG (F3165) and anti-His (H1029) antibodies were from Sigma. Anti-ADA2b (ab57953) antibody was from Abcam. Anti-MED6 (sc-9433) and anti-CDK8 (sc1521) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. IRDye700DX®-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (610–730-002), IRDye® 800-conjugated affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit IgG (611-732-127), IRDye® 800-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (605-732-002), and IRDye® 800-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgG (603-132-126) were from Rockland Immunochemicals. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were as follows: goat anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare, NA9340), goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, A4416), goat anti-chicken IgY (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., A30–206P). Glutathione donor beads (6765300) and nickel chelate acceptor beads (AL108C) for AlphaLISA® assays were from PerkinElmer. siRNA anti-MED25 (J-014689-11), siRNA smart pool anti-MED6 (L-019963-00-0005), and non-target siRNA (D-001810-10) were from Dharmacon. Thyroid hormone T3 (T7650) was from Sigma.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

GST-ATF6α-AD (ATF6α amino acids 1–150) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described (12). The MED25-VBD (MED25 amino acids 394–543) was cloned into pET21a with a C-terminal 6-histidine tag and transformed into BL-21 DE3 cells. Protein expression and purification were conducted as described (12) with the following modifications. Cells were harvested at 6000 × g and resuspended in 20 ml of 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.9, 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1:1000 protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and 20 mm β-mercaptoethanol. After lysis with a French Press, the cell suspension was brought to 0.1% Triton X-100 and 20 mm imidazole and clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 100,000 × g at 4 °C. 6-Histidine-MED25-VBD was purified from cell lysates using Nickel-NTA beads (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated in binding buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.9, 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1:1000 protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), 20 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 mm imidazole). Beads were washed four times with 10 ml of binding buffer and once with 10 ml of 40 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 100 mm NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1:1000 protease inhibitor mixture, 20 mm β-mercaptoethanol. Bound proteins were eluted with four bed volumes of the same buffer containing 300 mm imidazole. Purified protein was exchanged into buffer containing 40 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT (GB buffer) using a Zeba™ Desalting Column (Thermo Scientific).

Preparation of Mediator Complexes Containing Full-length MED25 or MED25-VWA

DNA fragments encoding full-length MED25 or MED25-VWA (MED25 amino acids 1–230) were amplified by PCR and introduced into the XhoI and Not1 restriction sites of a modified version of pcDNA5 (Invitrogen) that encodes an in-frame N-terminal FLAG tag (DYKDDDDK) just upstream of the XhoI site. To generate stable cell lines, HEK293-FRT cells were transfected with this plasmid together with pOG44, which encodes Flp recombinase, and hygromycin resistant clones stably expressing FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA were selected. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described (19) from 12 liters of cells grown in roller bottles. Mediator was purified as described (20) from 5 ml of nuclear extract using 100 μl of anti-FLAG M2-agarose beads. Assembly of FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA into Mediator was confirmed using MudPIT mass spectrometry (21) or Western blotting.

Affinity Chromatography

Glutathione affinity chromatography was performed as follows. 25 pmol of GST-ATF6α-AD was mixed with 25, 50, or 150 pmol of purified 6-histidine-MED25-VBD in GB buffer (40 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100, 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT) containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA in a total volume of 80 μl. After a 30- min incubation at 30 °C, binding reactions were combined with 20 μl of glutathione-Sepharose™ 4B equilibrated in GB buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C on a Nutator mixer (BD Diagnostics). The beads were then washed two times with 100 μl of GB buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA and once with GB buffer and eluted with 2 bed volumes of 20 mm glutathione in GB buffer. Alternatively, 25 pmol of GST-ATF6α- AD and 50 pmol of 6-histidine-MED25-VBD were mixed in 80 μl of GB buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA and 20 mm imidazole. The samples were incubated as above and then added to 20 μl of nickel-NTA AgaroseTM equilibrated in GB buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA and 20 mm imidazole. Beads were incubated and washed as described above and eluted with 2 bed volumes of GB buffer containing 300 mm imidazole.

Mass Spectrometry

Proteins were identified using a modification of the MudPIT procedure as described (21). Tandem mass (MS/MS) spectra were interpreted using SEQUEST (22) against a database of 29,147 non-redundant human proteins (downloaded from NCBI on August 16, 2011) supplemented with 160 usual contaminants. To estimate false positive discovery rates, each nonredundant sequence was randomized (keeping amino acid composition and length the same), and the resulting “shuffled” sequences were added to the “normal” database and searched at the same time. Peptide/spectrum matches were sorted and selected using DTASelect (23, 26) with the following criteria set. Spectra/peptide matches were only retained if they had a DeltaCn of at least 0.08 and a minimum XCorr of 1.8 for singly charged, 2.0 for doubly charged, and 3.0 for triply charged spectra. In addition, peptides had to be fully tryptic and at least 7 amino acids long. Combining all runs, proteins had to be detected by at least two such peptides or one peptide with two independent spectra. Peptide hits from multiple runs were compared using CONTRAST (23). To estimate relative protein levels, distributed normalized spectral abundance factors (dNSAFs) were calculated for each nonredundant protein or protein group as described (24). Accession numbers, sequence coverage, and numbers of spectra and unique peptides for each Mediator subunit identified are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Mediator Recruitment to Immobilized DNA Templates

Mediator-depleted Hela-S3 nuclear extracts were prepared as described (25) and dialyzed against 40 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, and 100 mm NaCl. Immobilized DNA binding assays were performed essentially as described (12). Briefly, saturating amounts of GAL4-DNA binding domain or GAL4 fusion proteins were incubated in binding buffer containing 20 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 80 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 1 mm DTT with 400 fmol of a biotinylated DNA fragment containing 5 GAL4 DNA binding sites upstream of the adenovirus major late promoter and immobilized on Dynabeads M-280 (Invitrogen) streptavidin magnetic beads. Unbound proteins were removed by washing twice with 100 μl of binding buffer. Equivalent amounts of Mediator purified through FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA were mixed with 37 μl of Mediator-depleted nuclear extract containing 150 μg/ml poly dI-dC and added to bead-bound DNA. The final buffer conditions in binding reactions were equivalent to binding buffer plus 0.05 mg/ml FLAG peptide, 60 mm KCl, 0.7 mm MgCl2, 0.04 mm Nonidet P-40, and 20 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9. After a 20-min incubation at room temperature, unbound proteins were removed by washing twice with binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and analyzed by Western blotting.

AlphaLISA Assays

1 μm purified 6-histidine-MED25-VBD, with or without 0.2 μm GST-ATF6 AD (1–150) in assay buffer (40 mm Hepes-NaOH pH 7.9, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5 mg/ml casein, 1 mm DTT, and 0.1% Antifoam A (Sigma), in a total volume of 8 μl, was added to individual wells of a non-binding, opaque 384 well assay plate (Corning 3574). The plate was covered with adhesive sealing foil, shaken for 5 min at 4000 rpm at room temperature on a plate shaker and incubated for an additional 10 min without shaking. Then, 2 μl of assay buffer alone or containing a competitor peptide in assay buffer was added to each well before the plates were resealed with adhesive foil and shaken for 5 min at 4000 rpm at room temperature. Following a 25-min incubation without shaking, 2.5 μl of AlphaLisa Nickel Chelate Acceptor beads (125 ng/ml), and 2.5 μl of AlphaScreen Glutathione Donor Beads (62.5 ng/ml) in assay buffer were added to each well, plates were resealed, shaken at 4000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature, and incubated an additional 85 min. AlphaLisa fluorescent signal was read using an EnVision multimodal plate reader (Perkin Elmer) using the AlphaScreen Label setting. The 32 amino acid competitor peptides consisted of 4 tandem repeats of the sequence DFDLDLLP (wild type) or DADADLLP (mutant).

siRNA-mediated Depletion of MED25 and MED6

Five 15 cm dishes of Hela-S3 cells stably expressing FLAG-MED19 (26, 27), were transfected with 10 nm siRNA for 72 h. For each plate, 33 μl of RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was mixed with 10 μl of 20 μm siRNA in 3.3 ml MEM and incubated for 20 min. The mixture was then added to a 15-cm plate containing 15 ml of DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1× Glutamax (Invitrogen). 2 ml of a cell suspension containing 5 × 106/ml cells in the same medium were added to each plate. After 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1× Glutamax. After 60 h, cells from one plate were harvested by TrypLE and replated on a 6-well plate at 5 × 105 cells/well. After 72 h, ER stress was induced in 3 of the 6 wells by addition of 500 nm thapsigargin. After 3.5 h, total RNA was isolated from a portion of the cells, and nuclear extracts were prepared as described above from the remaining cells. For measuring mRNA levels, cDNA was prepared from total RNA by reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using poly dT primer (Promega). HSPA5 transcript levels were determined by qPCR and normalized to 18S rRNA; qPCR was conducted using SYBR-green ready mix and iQ5 instrument (Bio-Rad). Primers were as follows: HSPA5: forward primer, 5′-CTGGGTACATTTGATCTGACTGG and reverse primer, 3′-GCATCCTGGTGGCTTTCCAGCCATTC. 18S rRNA: forward primer, 5′-TCAACTTTCGATGGTAGTCGCCGT and reverse primer, 5′-TCCTTGGATGTGGTAGCCGTTTCT.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Direct Binding of the ATF6α AD to MED25

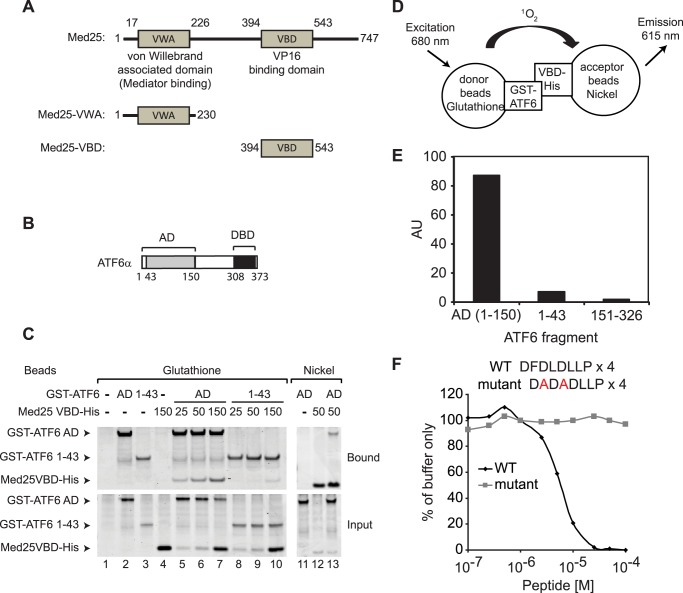

The VP16 AD has been shown to bind to the Mediator subunit MED25 via a domain referred to as the VP16 binding domain (VBD) located in its C terminus (Fig. 1A) (13–18). Because of our previous observation that VP16 AD competes with ATF6α for binding to Mediator, we asked whether the ATF6α AD (see Fig. 1B) could bind directly to the MED25 VBD in vitro. A GST-ATF6α-AD fusion protein including ATF6α amino acids 1–150 and a 6-histidine-MED25-VBD fusion protein including MED25 amino acids 394–543 were expressed in E. coli and purified. GST-ATF6α-AD was mixed with increasing amounts of 6-histidine-MED25-VBD and subjected to affinity chromatography using either glutathione-SepharoseTM or nickel-NTA AgaroseTM. As shown in the Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel in Fig. 1C, the purified GST-ATF6α-AD and 6-histidine-MED25-VBD bound directly and efficiently to one another (Fig. 1C, lanes 5–7 and lane 13). In contrast, a GST-ATF6α fusion protein that includes ATF6α amino acids 1–43 and which was found previously to bind poorly to Mediator, also bound poorly to the purified 6-histidine-MED25- VBD protein (Fig. 1C, lanes 8–10).

FIGURE 1.

Direct binding of the ATF6α AD to the MED25 VBD. A, diagram of MED25 mutants analyzed in this study. Numbers indicate amino acid residues. VWA, von Willebrand-associated domain; VBD, VP16 binding domain. B, diagram showing ATF6α AD and DBD. C, glutathione-Sepharose or nickel-agarose purifications (lanes 1–10 or lanes 11–13, respectively) were performed using 25 pmol of either GST-ATF6α-AD or a GST-ATF6α fusion protein containing ATF6α amino acids 1–43) with the indicated amounts of 6-histidine-MED25-VBD. SDS-polyacrylamide gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. D, diagram of the AlphaLISA assay. E, measurement of binding of ATF6α to the MED25 VBD. AU, arbitrary units. F, inhibition of ATF6α binding to the MED25 VBD by the VN8-like peptide. Each data point was normalized to the average of the signal obtained after addition of buffer alone and is expressed as the percent of signal obtained in the presence of MED25 VBD and ATF6α (% buffer only).

For a separate test of the ability of the ATF6α AD to bind directly to the MED25 VBD in vitro, we took advantage of the AlphaLISA system (28, 29). The AlphaLISA system has proven to be a sensitive method for real-time monitoring of protein-protein interactions. AlphaLISA assays exploit the short lifetime of singlet oxygen to initiate a chemiluminescent reaction that can occur only within a diffusion-limited distance of ∼200 nm from the site of singlet oxygen formation (29). In our assays, 6-histidine- MED25-VBD was bound to “acceptor” beads coupled to nickel, and GST-ATF6α-AD or GST-fusion proteins containing ATF6α residues 1–43 or 151–326, which do not bind to Mediator, were bound to “donor” beads coupled to glutathione. The donor beads contain a photosensitizing agent that excites oxygen to a singlet state when irradiated at 680 nm. Only when the donor and acceptor beads are held in close proximity through interactions between proteins on their surfaces can singlet oxygen produced by the donor beads reach the acceptor beads and promote chemiluminscent emission of light at 615 nm (Fig. 1D). When AlphaLISA assays were performed with GST-ATF6α-AD and 6-histidine-MED25-VBD, a strong chemiluminescent signal was observed (Fig. 1E). The interactions detected in these assays appear specific, since when we tested ATF6α-(1–43) or ATF6α-(151–326), which lack a functional AD, little or no signal was observed.

The ATF6α AD includes an eight amino acid sequence that is required for optimal ATF6α-dependent transcription activation in cells (30) and for binding to the Mediator complex in vitro (12). This sequence resembles a VP16 AD region referred to as VN8, which is essential for VP16 transcription activity and Mediator binding (13, 31, 32). A 32 amino acid peptide containing four repeats of the ATF6α VN8-like sequence blocks binding of GST-ATF6α-AD to Mediator (12). Similarly, we observed that this peptide interferes with binding of the ATF6α AD to the MED25 VBD in the AlphaLISA assay (Fig. 1F). We previously identified mutations in the ATF6α VN8-like sequence that prevent binding of ATF6α to Mediator. A control peptide containing 4 copies of the mutated ATF6α VN8-like sequence does not interfere with binding of the ATF6α AD to the MED25 VBD (Fig. 1F), suggesting that the interaction of ATF6α with free MED25 resembles its interaction with Mediator.

Requirement for the MED25 VBD in Binding of the ATF6α AD to Mediator

Having obtained evidence for a direct and specific interaction between the purified ATF6α AD and the MED25 VBD, we wished to determine whether the MED25 VBD contributes to binding of the ATF6α AD to the intact Mediator complex. As part of our effort to address this question, we used the Invitrogen FLP-in system to generate matching HEK293 cell lines stably expressing either wild type FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA, which lacks the VBD (Fig. 1A). To determine whether these FLAG-tagged proteins incorporate into Mediator, nuclear extracts prepared from cells expressing them were subjected to anti-FLAG M2 agarose chromatography, and FLAG-MED25- and FLAG-MED25-VWA-associated proteins were analyzed by MudPIT mass spectrometry and Western blotting.

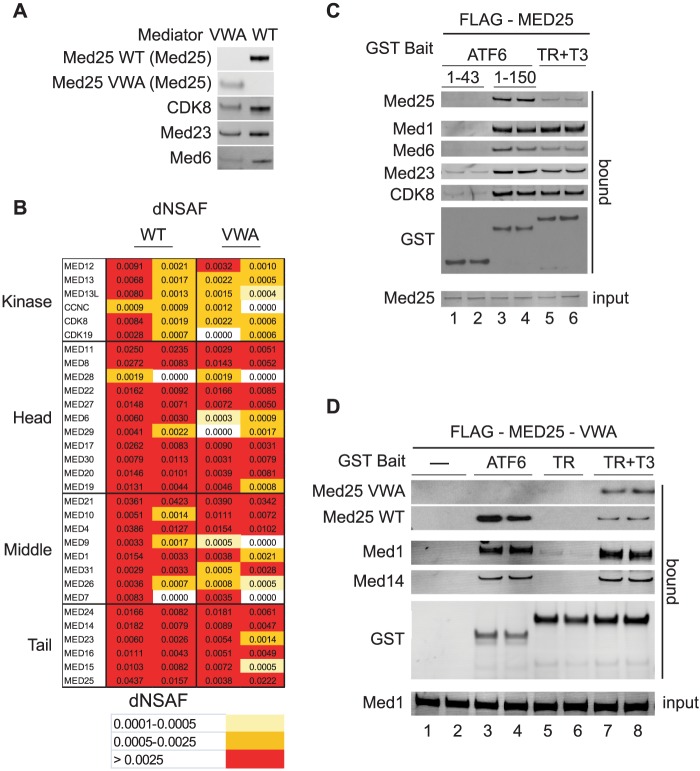

Although Western blotting with antibodies against the MED25-VWA (Fig. 2A) or with anti-FLAG (data not shown) revealed that FLAG-MED25-VWA is expressed at lower levels than its wild type counterpart, all of the Mediator subunits could be detected by MudPIT mass spectrometry in anti-FLAG agarose eluates from both FLAG-MED25 and FLAG-MED25-VWA-expressing cells (Fig. 2B). Thus, the MED25 VWA domain is sufficient for incorporation of MED25 into Mediator, consistent with previous results indicating that the MED25 VWA domain can bind Mediator subunits in Hela cell nuclear extracts (13). Notably, no endogenous MED25 could be detected in anti-FLAG agarose eluates from FLAG-MED25-VWA expressing cells (Fig. 2A), arguing that Mediator purified through FLAG-MED25-VWA is devoid of full-length MED25 and only one copy of MED25 is present in Mediator.

FIGURE 2.

The MED25 VWA domain directs MED25 incorporation into Mediator but does not bind the ATF6α AD. A, full-length FLAG-MED25- or FLAG-MED25-VWA-associated proteins were purified from cells stably expressing them by anti-FLAG-agarose chromatography (20). Western blot analyses of FLAG-MED25- and FLAG-MED25-VWA-associated proteins. The antibodies used are indicated in the figure. B, analyses of FLAG-MED25- and FLAG-MED25-VWA-associated proteins by MudPIT mass spectrometry. The distributed Normalized Spectral Abundance Factor (dNSAF) reflects the relative abundance of the different Mediator subunits in the samples (24). Two independent preparations of FLAG-MED25- and FLAG-MED25-VWA-associated proteins were analyzed. C, glutathione-Sepharose purification of Mediator from nuclear extracts of cells stably expressing FLAG-MED25. Binding reactions contained 20 μl of nuclear extract and 12 pmol of either GST-ATF6α-(1–150), GST-ATF6α-(1–43), or liganded GST-TR (supplemented with 1 μm thyroid hormone T3). Input (10% of total) and bound proteins were detected by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. D, glutathione-Sepharose purification of Mediator from 100 μl nuclear extract of cells stably expressing FLAG-MED25-VWA, using 12 pmol of GST-ATF6α-AD or liganded GST-TR. Bound Mediator subunits were detected by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

In initial experiments, we subjected nuclear extracts from both FLAG-MED25 and FLAG-MED25-VWA expressing cell lines to glutathione affinity chromatography to compare the binding of Mediator subunits to GST-ATF6α-AD and ligand-bound GST-thyroid receptor (TR), which has been shown previously to bind Mediator through interactions with MED1 (33–35). In the experiment of Fig. 2C, GST-ATF6α-AD or GST-TR were incubated with nuclear extracts from FLAG-MED25 expressing cells prior to glutathione chromatography. Very similar amounts of all Mediator subunits tested except FLAG-MED25 bound to GST-ATF6α-AD and GST-TR, but not to a control GST-ATF6α fusion protein containing ATF6α amino acids 1–43 (compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 5 and 6, and data not shown). In contrast, substantially more full-length MED25 bound to GST-ATF6α-AD than to GST-TR, consistent with the idea that ATF6α interacts directly with MED25.

Extracts from FLAG-MED25-VWA-expressing cells include a mixture of endogenous Mediator containing wild type MED25 and mutant Mediator containing FLAG-MED25-VWA. In addition, previous studies have shown that cells contain a substantial pool of free MED25 (13). When glutathione chromatography was performed with extracts from these cells, both activators again bound similar amounts of all Mediator subunits tested, and ATF6α bound more of the endogenous full-length MED25 (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 3 and 4 to lanes 7 and 8, and data not shown). Importantly, FLAG-MED25-VWA bound only when GST-TR was used as bait and only in the presence of TR ligand (T3). Taken together, these results are consistent with the idea that a mutant form of Mediator that contains the MED25 VWA but lacks the MED25 VBD can be targeted by liganded TR but not by the ATF6α AD.

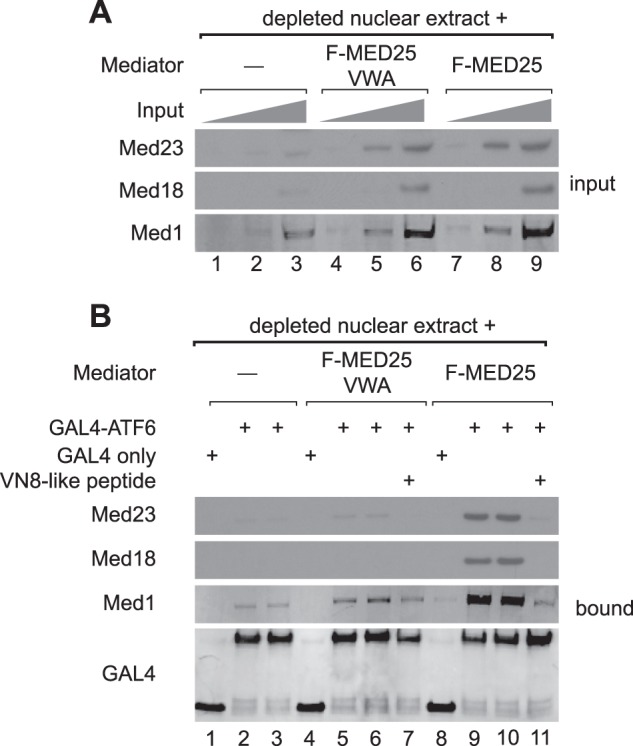

In a previous study, we showed that ATF6α could recruit Mediator to a promoter in vitro through Mediator-ATF6α AD interactions (12). To investigate the contribution of the MED25 VBD to this process, purified FLAG-MED25-VWA containing Mediator or wild type Mediator, purified through FLAG-MED25, were added to Mediator-depleted Hela-S3 nuclear extracts and incubated with a GAL4-ATF6α-AD fusion protein that includes ATF6α amino acids 1–150 and that had been pre-bound to an immobilized biotinylated DNA fragment containing 5 GAL4 DNA binding sites just upstream of the adenovirus major late core promoter. Remarkably, while similar amounts of Mediator containing either full-length FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA were introduced into the assay (Fig. 3A), Mediator containing full-length FLAG-MED25 was preferentially recruited to the DNA by GAL4-ATF6α-AD (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 5, 6 to 9,10). These observations correlate with the lack of binding of FLAG-MED25-VWA to GST-ATF6α-AD in nuclear extracts from FLAG-MED25-VWA-expressing HEK293 cells (Fig. 2D, lanes 3, 4) and are consistent with the model that ATF6α is unable to bind to Mediator containing FLAG-MED25-VWA and requires the MED25 VBD for targeting Mediator.

FIGURE 3.

Mediator containing FLAG-MED25-VWA is not efficiently recruited to promoter DNA in vitro by ATF6α. Promoter binding assays were performed using Mediator purified through FLAG-MED25 or FLAG-MED25-VWA, nuclear extracts that had been depleted of Mediator, and either the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GAL4) or a GAL4-ATF6α-AD fusion protein containing ATF6α amino acids 1–150. A, Western blots of representative Mediator subunits present in 3% (lanes 1, 4, and 7), 9% (lanes 2, 5, and 8), or 27% (lanes 3, 6, and 9) of input binding reactions prior to separation of DNA-bound and unbound fractions. B, Western blots of representative Mediator subunits in DNA-bound fractions. Proteins were detected using the indicated antibodies.

To test whether the interaction of ATF6α with Mediator containing full-length FLAG-MED25 is specific and resembles the interaction of ATF6α with endogenous Mediator, we used the VN8-like peptide as an indicator. As noted above, this peptide competes with endogenous Mediator for binding to ATF6α but not to liganded TR, consistent with the importance of the ATF6α VN8-like sequence for binding of ATF6α to Mediator (12). As shown in Fig. 3B, the VN8-like peptide effectively blocked binding of GST-ATF6α-AD to Mediator containing FLAG-MED25 in Mediator-depleted nuclear extracts, recapitulating the effect of the peptide on binding of ATF6α to endogenous Mediator (Fig. 3B compare lanes 9 and 10 to lane 11).

MED25 Is Needed for Optimal Binding of ATF6α to Mediator and for ATF6α-dependent Transcription in Response to ER Stress

We next tested the contribution of endogenous MED25 to the ATF6α-Mediator interaction. Hela-S3 cells were grown in the presence of a control non-targeting siRNA or siRNAs targeting MED25 or another Mediator subunit, MED6, which has been shown to be required for expression of about 10% of genes in yeast and of many, but not all, genes in Drosophila (36–38). Mediator can be subdivided into subassemblies referred to as the head, middle, tail, and kinase modules (reviewed in Refs. 39, 40). MED25 is likely a component of the tail module,4 while MED6 is located on the surface of the Mediator head module (41–43) and can be removed without disrupting the larger Mediator complex (36, 44).

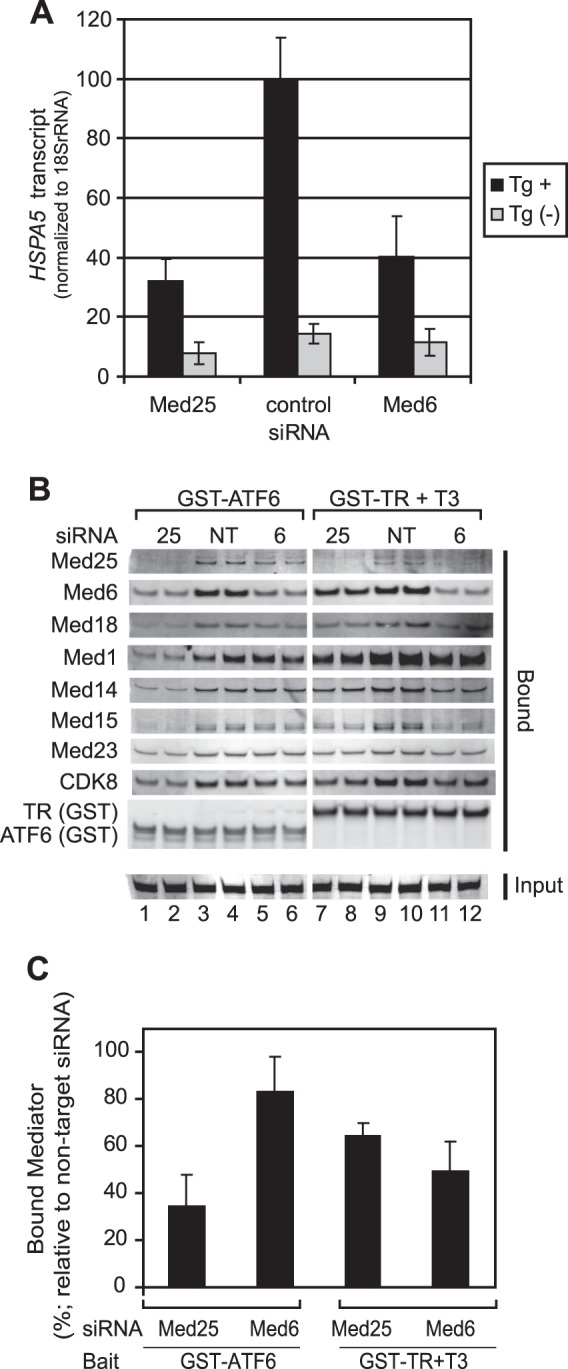

ATF6α is a master regulator of ER stress-induced genes, including HSPA5 (4, 9–11), and we have previously presented evidence that ATF6α can recruit Mediator to the ERSE of the HSPA5 promoter (12). Confirming a role for Mediator in ATF6α-dependent gene expression, we observed that thapsigargin induction of HSPA5 was attenuated in cells treated with siRNAs targeting either MED25 or MED6 (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

siRNA-mediated MED25 depletion interferes with the ATF6α-Mediator interaction and with ER stress-induced HSPA5 expression. A, siRNA-mediated depletion of MED25 and MED6 attenuates HSPA5 expression. RNA was purified from multiple independent cultures grown in parallel with those used in the experiment shown in panels A and B. Thapsigargin (Tg) was used to induce ER stress. HSPA5 mRNA from untreated and Tg-treated cells was assayed by qPCR and normalized to 18 S rRNA. Values shown in the graph are the average of three biological replicates; error bars represent the S.D. B, effect of depleting MED25 or MED6 on binding of Mediator to GST-ATF6α-AD or liganded GST-TR. Glutathione-Sepharose chromatography was carried out using 12 pmol of GST-ATF6α-AD or liganded GST-TR and 40 μl of nuclear extracts prepared from cells that had been treated with non-targeting siRNA or siRNAs against MED25 or MED6. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated primary antibodies and detected using appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to IRDye700DX or IRDye800. IRDye- labeled secondary antibodies were detected using a Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system. Duplicate lanes show results obtained in two independent purifications from the same extract. C, quantitation of data shown in panel A. The intensities of bands corresponding to MED1, MED14, MED15, MED18, andMED23 were determined using Odyssey infrared imaging system application software version 3.0 (Li-Cor) in the Median background mode. Relative recovery of Mediator in cells treated with MED25 or MED6 siRNA was calculated by first determining the % recovery of each subunit in bound fractions from siRNA-treated cells relative to the average of the same subunit in fractions from cells treated with non-targeting siRNA and then averaging the values obtained for all subunits; error bars are S.D.

To assess the effect of MED25 or MED6 depletion on binding of Mediator to ATF6α, nuclear extracts were prepared from cultures of siRNA-treated cells grown in parallel with those used to assess HSPA5 gene expression and subjected to glutathione affinity chromatography using either GST-ATF6α-AD or, as a control, liganded GST-TR. Bound fractions were subjected to Western blotting using antibodies against representative subunits from each Mediator module (Fig. 4B); Western blot signals were visualized with fluorescent secondary antibodies and quantitated using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Fig. 4, B and C).

Consistent with the idea that MED25 makes an important contribution to the ATF6α-Mediator interaction, we observed that depletion of endogenous MED25 led to a significantly greater reduction, relative to control, in binding of Mediator subunits to GST-ATF6α-AD (compare lanes 1 and 2 to lanes 3 and 4), than did MED6 depletion (p value calculated using a two-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance = 4 × 10−5) (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1, 2 to 5, 6 and Fig. 4C). In addition, MED25 knockdown had a more pronounced effect on binding of Mediator subunits to GST-ATF6α-AD than to liganded GST-TR in these assays (p = 0.002; Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1, 2 to lanes 7, 8). Finally, binding of Mediator subunits to liganded GST-TR was affected similarly by MED25 or MED6 depletion.

Summary

In this study, we have investigated the mechanism by which the ER stress response transcription factor ATF6α recruits the human Mediator complex to the genes it regulates. We present several lines of evidence consistent with the idea that ATF6α recruits Mediator to ER stress response genes via direct interactions with its MED25 subunit. First, consistent with our previous observation that the VP16 AD competes with ATF6α for binding to Mediator in nuclear extracts (12), we observe that the purified ATF6α AD binds stably and specifically in vitro to the purified MED25 VBD, a MED25 domain previously shown to be the binding site on Mediator for the viral VP16 AD (13–18). Second, in reconstitution experiments, we obtained evidence that Mediator containing a MED25 mutant that lacks the VBD fails to bind efficiently to ATF6α but binds to liganded thyroid receptor, which is known to bind to Mediator through LXXLL motifs in its MED1 subunit (33–35). Third, we obtained evidence that siRNA-mediated depletion of MED25 from human HeLa-S3 cells results both in reduced binding of the ATF6α AD to Mediator in nuclear extracts prepared from siRNA-treated cells and in reduced ATF6α-dependent transcription of the HSPA5 gene in response to thapsigargin-induced ER stress. Depletion of MED25 or the head module subunit MED6 decreased HSPA5 gene expression in cells to a similar extent, while MED25 depletion had a more pronounced effect on binding of the ATF6α AD to Mediator, most likely due to a role for MED6 in additional Mediator functions. In this regard, it is noteworthy that MED6, along with other subunits of the Mediator head module, has been shown to bind directly to heptapeptide repeats in the C-terminal domain of the largest Pol II subunit (43).

Taken together, our findings argue that ATF6α targets human Mediator at least in part through direct, physical interactions with the MED25 VBD. Our findings do not rule out the possibility that ATF6α also makes important contacts with other Mediator subunits during its recruitment of Mediator to ERSEs in ER stress response genes or during subsequent stages of transcription activation. We have thus far not obtained antibodies sufficient for exploiting chromatin immunoprecipitation to determine whether Mediator containing mutant MED25 lacking the VBD can still be recruited by ATF6α to ER stress response genes. In the future, with the generation of better antibodies, we expect that it will be possible to answer this question and, in so doing, shed further light on the mechanism by which ATF6α activates transcription and the role of MED25 in this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chieri Tomomori-Sato for helpful discussions, Damon Sheets for expert technical assistance, and Holly Zink for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM041628 (to R. C. C. and J. W. C.) and by a grant to the Stowers Institute from the Helen Nelson Medical Research Fund at the Greater Kansas City Community Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Table S1.

S. Sato, C. Tomomori-Sato, J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway, unpublished results.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERSE

- ER stress response element

- AD

- transcription activation domain

- ATAC

- Ada-Two-A-containing

- dNSAF

- distributed normalized spectral abundance factor

- HAT

- histone acetyl transferase

- MudPIT

- multidimensional protein identification technology

- Pol II

- RNA polymerase II

- SAGA

- Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyl transferase

- TR

- thyroid receptor

- VBD

- VP16 binding domain

- VWA

- von Willebrand associated domain

- DBD

- DNA binding domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schröder M., Kaufman R. J. (2005) The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 739–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ron D., Walter P. (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang K., Kaufman R. J. (2008) From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 454, 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. (1999) Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3787–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ye J., Rawson R. B., Komuro R., Chen X., Davé U. P., Prywes R., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2000) ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol. Cell 6, 1355–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen X., Shen J., Prywes R. (2002) The luminal domain of ATF6 senses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and causes translocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13045–13052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shen J., Chen X., Hendershot L., Prywes R. (2002) ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev. Cell 3, 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shen J., Prywes R. (2004) Dependence of site-2 protease cleavage of ATF6 on prior site-1 protease digestion is determined by the size of the luminal domain of ATF6. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43046–43051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshida H., Haze K., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. (1998) Identification of the cis-acting endoplasmic reticulum stress response element responsible for transcriptional induction of mammalian glucose-regulated proteins. Involvement of basic leucine zipper transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33741–33749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoshida H., Okada T., Haze K., Yanagi H., Yura T., Negishi M., Mori K. (2000) ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 6755–6767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamamoto K., Sato T., Matsui T., Sato M., Okada T., Yoshida H., Harada A., Mori K. (2007) Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6alpha and XBP1. Dev. Cell 13, 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sela D., Chen L., Martin-Brown S., Washburn M. P., Florens L., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C. (2012) Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-responsive Transcription Factor ATF6alpha Directs Recruitment of the Mediator of RNA Polymerase II Transcription and Multiple Histone Acetyltransferase Complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23035–23045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mittler G., Stühler T., Santolin L., Uhlmann T., Kremmer E., Lottspeich F., Berti L., Meisterernst M. (2003) A novel docking site on Mediator is critical for activation by VP16 in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 22, 6494–6504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang F., DeBeaumont R., Zhou S., Näär A. M. (2004) The activator-recruited cofactor/Mediator coactivator subunit ARC92 is a functionally important target of the VP16 transcriptional activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2339–2344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bontems F., Verger A., Dewitte F., Lens Z., Baert J. L., Ferreira E., de Launoit Y., Sizun C., Guittet E., Villeret V., Monté D. (2011) NMR structure of the human Mediator MED25 ACID domain. J. Struct. Biol. 174, 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vojnic E., Mourão A., Seizl M., Simon B., Wenzeck L., Lariviere L., Baumli S., Baumgart K., Meisterernst M., Sattler M., Cramer P. (2011) Structure and VP16 binding of the Mediator Med25 activator interaction domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 404–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milbradt A. G., Kulkarni M., Yi T., Takeuchi K., Sun Z. Y., Luna R. E., Selenko P., Näär A. M., Wagner G. (2011) Structure of the VP16 transactivator target in the Mediator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 410–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eletsky A., Ruyechan W. T., Xiao R., Acton T. B., Montelione G. T., Szyperski T. (2011) Solution NMR structure of MED25(391–543) comprising the activator-interacting domain (ACID) of human mediator subunit 25. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 12, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. (1983) Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian cell nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomomori-Sato C., Sato S., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2013) Immunoaffinity purification of protein complexes from Mammalian cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 977, 273–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Florens L., Washburn M. P. (2006) Proteomic analysis by multidimensional protein identification technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 328, 159–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eng J. K., McCormack A. L., Yates J. R., III (1994) An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spec. 5, 976–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tabb D. L., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R., 3rd. (2002) DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 1, 21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Y., Wen Z., Washburn M. P., Florens L. (2010) Refinements to label free proteome quantitation: how to deal with peptides shared by multiple proteins. Anal. Chem. 82, 2272–2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson K. M., Wang J., Smallwood A., Arayata C., Carey M. (2002) TFIID and human mediator coactivator complexes assemble cooperatively on promoter DNA. Genes Dev. 16, 1852–1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sato S., Tomomori-Sato C., Banks C. A., Sorokina I., Parmely T. J., Kong S. E., Jin J., Cai Y., Lane W. S., Brower C. S., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2003) Identification of mammalian Mediator subunits with similarities to yeast Mediator subunits Srb5, Srb6, Med11, and Rox3. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15123–15127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sato S., Tomomori-Sato C., Banks C. A., Parmely T. J., Sorokina I., Brower C. S., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2003) A mammalian homolog of Drosophila melanogaster transcriptional coactivator Intersex is a subunit of the mammalian Mediator complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49671–49674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eglen R. M., Reisine T., Roby P., Rouleau N., Illy C., Bossé R., Bielefeld M. (2008) The use of AlphaScreen technology in HTS: current status. Curr. Chem. Genomics 1, 2–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ullman E. F., Kirakossian H., Singh S., Wu Z. P., Irvin B. R., Pease J. S., Switchenko A. C., Irvine J. D., Dafforn A., Skold C. N. (1994) Luminescent oxygen channeling immunoassay: measurement of particle binding kinetics by chemiluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5426–5430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thuerauf D. J., Morrison L. E., Hoover H., Glembotski C. C. (2002) Coordination of ATF6-mediated transcription and ATF6 degradation by a domain that is shared with the viral transcription factor, VP16. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20734–20739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molinari E., Gilman M., Natesan S. (1999) Proteasome-mediated degradation of transcriptional activators correlates with activation domain potency in vivo. EMBO J. 18, 6439–6447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ikeda K., Stuehler T., Meisterernst M. (2002) The H1 and H2 regions of the activation domain of herpes simplex virion protein 16 stimulate transcription through distinct molecular mechanisms. Genes Cells 7, 49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fondell J. D., Ge H., Roeder R. G. (1996) Ligand induction of a transcriptionally active thyroid hormone receptor coactivator complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8329–8333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yuan C. X., Ito M., Fondell J. D., Fu Z. Y., Roeder R. G. (1998) The TRAP220 component of a thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein (TRAP) coactivator complex interacts directly with nuclear receptors in a ligand-dependent fashion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7939–7944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malik S., Guermah M., Yuan C. X., Wu W., Yamamura S., Roeder R. G. (2004) Structural and functional organization of TRAP220, the TRAP/mediator subunit that is targeted by nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 8244–8254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee Y. C., Min S., Gim B. S., Kim Y. J. (1997) A transcriptional mediator protein that is required for activation of many RNA polymerase II promoters and is conserved from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 4622–4632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holstege F. C., Jennings E. G., Wyrick J. J., Lee T. I., Hengartner C. J., Green M. R., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., Young R. A. (1998) Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95, 717–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gim B. S., Park J. M., Yoon J. H., Kang C., Kim Y. J. (2001) Drosophila Med6 is required for elevated expression of a large but distinct set of developmentally regulated genes. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 5242–5255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chadick J. Z., Asturias F. J. (2005) Structure of eukaryotic Mediator complexes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 264–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2011) Function and regulation of the Mediator complex. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Imasaki T., Calero G., Cai G., Tsai K. L., Yamada K., Cardelli F., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Berger I., Kornberg G. L., Asturias F. J., Kornberg R. D., Takagi Y. (2011) Architecture of the Mediator head module. Nature 475, 240–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Larivière L., Plaschka C., Seizl M., Wenzeck L., Kurth F., Cramer P. (2012) Structure of the Mediator head module. Nature 492, 448–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robinson P. J., Bushnell D. A., Trnka M. J., Burlingame A. L., Kornberg R. D. (2012) Structure of the mediator head module bound to the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 17931–17935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takagi Y., Calero G., Komori H., Brown J. A., Ehrensberger A. H., Hudmon A., Asturias F., Kornberg R. D. (2006) Head module control of mediator interactions. Mol. Cell 23, 355–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]