Abstract

Background and Purpose

The recently proposed binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines to the human (h) histamine H4 receptor suggests that the 2-amino group of these ligands interacts with glutamic acid residue E1825.46 in the transmembrane (TM) helix 5 of this receptor. Interestingly, substituents at the 2-position of this pyrimidine are also in close proximity to the cysteine residue C983.36 in TM3. We hypothesized that an ethenyl group at this position will form a covalent bond with C983.36 by functioning as a Michael acceptor. A covalent pyrimidine analogue will not only prove this proposed binding mode, but will also provide a valuable tool for H4 receptor research.

Experimental Approach

We designed and synthesized VUF14480, and pharmacologically characterized this compound in hH4 receptor radioligand binding, G protein activation and β-arrestin2 recruitment experiments. The ability of VUF14480 to act as a covalent binder was assessed both chemically and pharmacologically.

Key Results

VUF14480 was shown to be a partial agonist of hH4 receptor-mediated G protein signalling and β-arrestin2 recruitment. VUF14480 bound covalently to the hH4 receptor with submicromolar affinity. Serine substitution of C983.36 prevented this covalent interaction.

Conclusion and Implications

VUF14480 is thought to bind covalently to the hH4 receptor-C983.36 residue and partially induce hH4 receptor-mediated G protein activation and β-arrestin2 recruitment. Moreover, these observations confirm our previously proposed binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines. VUF14480 will be a useful tool to stabilize the receptor into an active confirmation and further investigate the structure of the active hH4 receptor.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed issue on Histamine Pharmacology Update. To view the other articles in this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2013.170.issue-1

Keywords: covalent binder, histamine H4 receptor, GPCR, pyrimidine

Introduction

The human (h) histamine H4 receptor belongs to the GPCR subfamily of four histamine receptors and is considered to be an important receptor in the regulation of inflammatory processes (Nijmeijer et al., 2012a). Therapeutic intervention of this receptor is thought to be beneficial in disorders such as allergic asthma, pruritus and rheumatoid arthritis (Leurs et al., 2011). Since the identification of this histamine receptor in 2000, many carboxamides and pyrimidines have been found to be H4 receptor antagonists (Engelhardt et al., 2009; Smits et al., 2009; Figure 1A). The indolecarboxamide JNJ 7777120 was one of the first compounds found to be a selective H4 receptor antagonist as a result of a high throughput screening campaign followed by lead optimization (Jablonowski et al., 2003) (Figure 1A). Originally it was thought that JNJ 7777120 was only an antagonist, as it inhibits histamine-induced Gαi protein signalling, but, recently, from its effects on H4 receptor-mediated β-arrestin2 signalling it has also been shown to be a partial agonist (Rosethorne and Charlton, 2011; Nijmeijer et al., 2012b). More rational approaches, such as scaffold-optimization and -hopping or fragment-based drug design, have led to the development of 2,4 diaminopyrimidines, quinoxalines and quinazolines as H4 receptor antagonists (Smits et al., 2008; 2010; Sander et al., 2009).

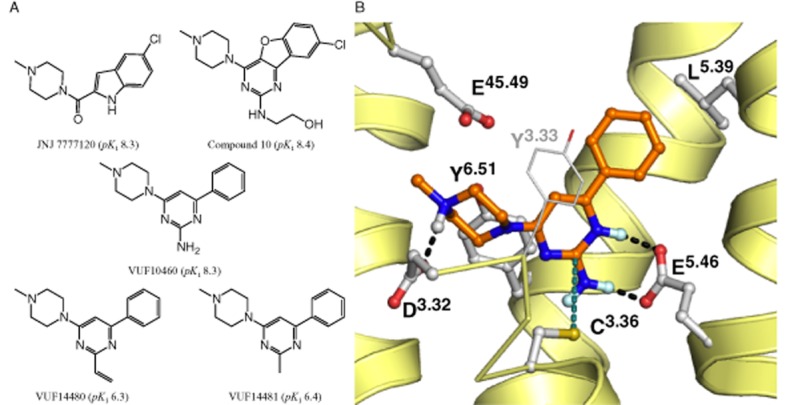

Figure 1.

Rational design of a covalent hH4 receptor ligand. (A) Chemical structures of hH4 receptor antagonists. JNJ 7777120, Compound 10 from Janssen Pharmaceutica (Chavez et al., 2008), 2-amino pyrimidine VUF10460, VUF14480 and VUF14481. (B) Binding mode of VUF10460 in the previously validated hH4 receptor homology model (Schultes et al., 2013b) based on the hH1 receptor crystal structure template (Shimamura et al., 2011). The amino group at position 2 of 2-aminopyrimidines interacts with E1825.46 (Schultes et al., 2013b). In addition, substituents at this position are also in close proximity to C983.36 as indicated by the green dotted line (distance ring carbon to thiol group of C983.36 is 4.2 Å). The backbone of TM helices 5, 6 and 7 (right to left) are presented as yellow helices, TM3 is presented as a yellow ribbon in the front. Important binding residues are depicted as ball-and-stick models with grey carbon atoms. Oxygen, nitrogen sulfur and polar hydrogen atoms are coloured red, blue, yellow and light blue respectively. H-bonds between VUF10460 and hH4 receptors are depicted by black dotted lines.

Computer-aided drug discovery has provided valuable insight into the shape and properties of GPCR ligand-binding pockets. Three-dimensional models based on the rhodopsin (Palczewski et al., 2000) or β2-adrenoceptor X-ray structures (Cherezov et al., 2007), in combination with site-directed mutagenesis and structure activity relationship data, were used to identify interaction points in the hH4 receptor that are crucial for ligand binding (Jongejan et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2010; Istyastono et al., 2011a,b; Wijtmans et al., 2011; Schultes et al., 2013b). In 2011, the more closely related doxepin-bound histamine hH1 receptor crystal structure was elucidated (Shimamura et al., 2011). On the basis of this crystal structure-based homology model of the hH1 receptor, we recently investigated the binding mode of indolecarboxamides and 2-aminopyrimidines in the binding pocket of the hH4 receptor, (Figure 1A, B) (Schultes et al., 2013a,b). The proposed binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines involves a strong interaction between the 2-amino substituent and glutamic acid residue E1825.46 in transmembrane (TM) helix 5 of the hH4 receptor (the superscript residue numbers are according to the Ballesteros Weinstein numbering; Ballesteros and Weinstein, 1995). Residues in extracellular loop 2 have been numbered 45.x, in which 45 refers to the position between helix 4 and 5 and x refers to a number that indicates its position relative to the conserved cysteine residue 45.50 (De Graaf et al., 2008). Moreover, the model predicts that substituents at position 2 of the pyrimidine are in close proximity (<2 Å) to the cysteine residue C983.36 in TM3 (Figure 1B). In addition, substituents of considerable size can be present at this position without loss of affinity (Figure 1A, compound 10). Interestingly, the nucleophilic thiol side chain of cysteines can form an irreversible bond with unsaturated carbonyl groups (i.e. Michael acceptor; Ekici et al., 2004; Tsou et al., 2005; Klutchko et al., 2006; Pan et al., 2007; Garuti et al., 2011). Hence, we hypothesized that the introduction of an ethenyl at position 2 of the pyrimidine ring might result in a compound that can covalently interact with C983.36. Covalent binders are considered useful as tool compounds, for example, when studying protein structure. This would be particularly useful in the current era, where numerous GPCR crystal structures are being elucidated, as the need for a ligand that has a long residence time might be beneficial for co-crystallization with its receptor (Rosenbaum et al., 2011). Moreover, a covalent interaction in the binding pocket can unequivocally confirm a proposed ligand-binding model.

In this study, we describe the rational design of the pyrimidine derivate VUF14480 (Figure 1A) that covalently binds and partially activates the hH4 receptor. The pyrimidine compound contains a Michael acceptor that is in close proximity to C983.36, which was identified as an anchor point for a covalent interaction.

Methods

Materials

Cell culture media were bought from PAA (Pasching, Austria), [3H]-histamine (10.6–15.3 Ci·mmol−1) and [35S]-GTPγS (1250 Ci·mmol−1) were purchased from Perkin Elmer (Groningen, The Netherlands). Chemicals and reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. L-glutathione reduced was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA) and L-cysteine ethyl ester hydrochloride was purchased from Janssen Chimica (Beerse, Belgium). The synthesis of VUF14480 and VUF14481 is described in the Supporting Information.

Site-directed mutagenesis of C983.36 and construction of hH4 receptor-Rluc8 and β-arrestin2-mVenus

The C983.36S was constructed via PCR-mediated mutagenesis. Wild-type (WT)-hH4 receptors (pcDEF3) were amplified in the presence of 0.1 mM dNTPs and 10 U Pfu polymerase and 10 pM forward plasmid primer (5′-CATTCTCAAgCCTCAgACAgTgg-3′) in combination with 10 pM reverse mutagenesis primer (5′-CAgATgCTgTAgACAACAgATAg-3′), and 0.5 μM forward mutagenesis primer (5′-CTATCTgTTgTCTACAgCATCTg-3′) in combination with 0.5 μM reverse plasmid primer (5-gAgCTCTAgCATTTAggTgACAC-3′). The PCR programme consisted of 25 cycles of 95°C-30 s, 60°C-30 s, 72°C-60 s. The two PCR products were isolated from agarose gel. The PCR products from both mutagenesis reactions were fused in a self-primed PCR and subsequently amplified using flanking primers PCR programme: 25 cycles of 95°C-30 s, 55°C-30 s, 72°C-90 s. Fused PCR products were isolated from agarose gel, digested with KpnI and XbaI and inserted into the expression vector pcDEF3. The sequences of the C983.36S DNA obtained were verified.

Construction of hH4 receptor-Rluc8 was as described previously (Nijmeijer et al., 2010). The β-arrestin2-mVenus construct was created using the same procedure. DNA plasmid encoding the mVenus protein was a kind gift of Dr J. A. Javitch (Columbia University, New York, NY, USA) (Guo et al., 2008).

Cell culture, transfection and membrane preparation

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 IU·mL−1 penicillin, and 50 μg·mL−1 streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Two million cells were seeded per 10 cm dish one day prior to transfection. Approximately 4E6 cells were transfected with 5 μg of cDNA using the polyethylenimine (PEI) method. Briefly, for binding experiments, 2.5 μg hH4R(-C983.36S) cDNA was supplemented with empty pcDEF3 plasmid to produce a total of 5 μg cDNA; for BRET-based β-arrestin2 recruitment, 1 μg hH4 receptor(-C983.36S)-Rluc8 and 4 μg β-arrestin2-mVenus were mixed with 20 μg of 25 kDa linear PEI in 500 μL of 150 mM NaCl. This transfection mixture was incubated at 22°C for 10–30 min. Meanwhile, the medium in the 10 cm dish was replaced with 6 mL of fresh culture medium and transfection mix was then added dropwise to the cells. Two days after transfection, transfected cells were washed once with PBS and subsequently scraped from their culture dish in 1 mL of PBS. Crude membrane pellets were collected by centrifugation at ∼2000× g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −20°C until further use.

S-alkylation of glutathione or cysteine ethyl ester by VUF14480 or VUF14481

VUF14480 and VUF14481 were mixed with glutathione or cysteine ethyl ester in a 1:1 molar ratio and incubated overnight at 22°C. The incubated mixtures were subsequently separated and analysed by LCMS.

[3H]-histamine displacement binding

Crude membrane pellet was dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4 at 22°C) and incubated with increasing concentrations (10 pM–100 μM) of the indicated compounds and [3H]-histamine (∼10 nM) for 1.5 h with crude membrane suspensions. The reaction was terminated by filtration through a PEI (0.5%) soaked GF/C plate (Perkin Elmer), followed by three washes with ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4 at 4°C). Microscint O scintillation fluid was added and radioactivity was counted in a Wallac Microbeta counter (Perkin Elmer).

Membrane preparation for [35S]-GTPγS binding

Two days after transfection, cells were washed with 2 mL PBS and harvested in 2.5 mL membrane buffer (15 mM Tris, 1 mM EGTA, 0.3 mM EDTA and 2 mM MgCl2; pH 7.4 at 4°C). The cell homogenate was sonicated for 20 s and centrifuged for 30 min, 2000× g at 4°C. The supernatant was aspirated and the membrane pellet was resuspended in 250 μL Tris-sucrose (20 mM Tris and 250 mM sucrose, pH 7.4 at 4°C) per dish. Membranes were stored at −80°C until further use.

[35S]-GTPγS-binding assay

Membranes (10 μg per well) were incubated in GTPγS assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 at 22°C, supplemented with 0.2 μg·μL−1 saponin, 3 μM GDP and 0.5 nM [35S]-GTPγS) with increasing amount (1 nM–10 μM) of the indicated compounds for 1 h at 22°C. [35S]-GTPγS binding was terminated by rapid filtration through unifilter GF/B plates (Perkin Elmer). Filter plates were washed three times with ice-cold washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl and 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 at 4°C). Microscint O scintillation fluid (Perkin Elmer) was added and the radioactivity was counted in a Wallac Microbeta counter.

BRET-based β-arrestin2 recruitment

One day post-transfection, cells were seeded in a poly-L-lysine-coated, white bottom, 96 well plate. Next day, the medium was aspirated and replaced with PBS. Coelenterazine-h (5 μM final concentration) and indicated ligands (10 μM final) were added to the cells and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, BRET (em. 535 nm) and Rluc8 (em. 460 nm) were measured on a Victor3 (Perkin Elmer). BRET ratios (BRET divided by Rluc8 emission signal) were corrected for BRET ratios measured in cells that only express hH4 receptor (C983.36S)-Rluc8.

Pre-incubation experiments prior to heterologous displacement binding

Crude membrane fractions were pre-incubated for 1 h at 22°C on a roller bench with either 50 mM Tris-HCl or increasing amounts (100 nM–10 μM) of VUF14480, VUF14481 or JNJ 7777120. Next, treated membrane fractions were washed three times with 1 mL 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Washing includes incubation for 10 min at 22°C on a roller bench and every 2 min a 30 s vortexing step. Finally, membranes were dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl. Aliquots, 50 μL, of the pretreated membranes were subsequently used in the previously described [3H]-histamine binding studies.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

All data were analysed with GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Homologous and heterologous displacement-binding data were fitted to a one-site competition model. Functional concentration response curves were fitted to a three-parameter concentration response model. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's unpaired t-test (****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05).

Construction of three-dimensional binding mode models for VUF14481 and VUF14480 in the hH4 receptor-binding pocket

The binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines was used as an initial binding model (Schultes et al., 2013b). The 2-amino group was removed and rebuilt using the MOE version 2011.10 (MOE, 2011). The models were subjected to energy minimization using the MMFF94x force field with fixed position of the backbone atoms of the protein.

Results

Synthesis VUF14480 and VUF14481

VUF14480 was designed and synthesized based on the previously suggested binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines (Figure 1B) and the hypothesis that an ethenyl substituent at position 2 of the pyrimidine scaffold can act as a Michael acceptor (Liu et al., 1999; Karagiorgou et al., 2005). Due to the electron-deficient heteroaromatic pyrimidine ring, the ethane residue is polarized so that the nucleophilic thiol side chain of cysteine can react at the β-carbon of the alkene. Furthermore, based on the binding model of 2-aminopyrimidines (Figure 1B), the thiol from C983.36 displays a conformation similar to the proposed 2-ethenylpyrimidine, which is favourable for the Michael-type addition reaction (Tsou et al., 2005). As a control, we synthesized VUF14481 with a methyl substituent at the 2-position and a similar proposed binding mode, but without the option to function as a Michael acceptor (Figure 1A, Supporting Information).

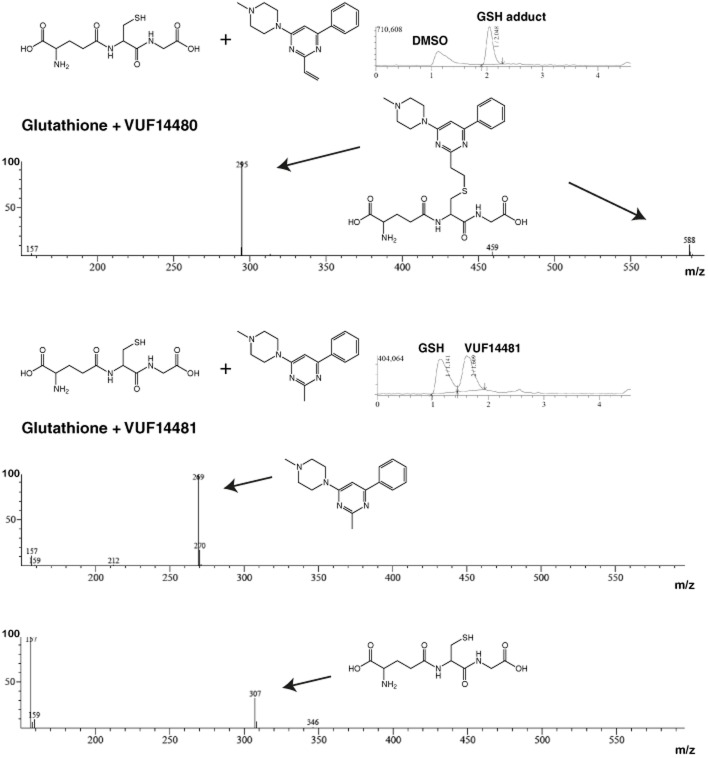

Covalent binding of VUF14480 and VUF14481 to glutathione or cysteine ethyl ester

VUF14480 and VUF14481 were first tested for their ability to react with either glutathione or the cysteine ethyl ester. To this end, both compounds were mixed with either glutathione or cysteine ethyl ester in a 1:1 molar ratio and incubated overnight at 22°C. The incubated mixtures were subsequently separated and analysed by LCMS (Figure 2). Incubation of VUF14480 with glutathione resulted in a reaction product (588 g·mol−1), which corresponded to the sum of the masses of VUF14480 (281 g·mol−1) and glutathione (307 g·mol−1). In addition, we observed a peak with mass 295 g·mol−1 that could be explained by a reaction product that is double protonated (i.e. the m/z ratio consequently resulted in m+2/2).. The reaction between VUF14480 and the cysteine ethyl ester yielded an expected mass peak of 430 g·mol−1 as well as 216 g·mol−1 that corresponded to a double protonated product. Moreover, we observed a small peak of 281 g·mol−1, which equals the mass of compound VUF14480. In contrast, the control compound VUF14481 did not react with either glutathione or the cysteine ethyl ester in a covalent manner and only the mass of the initial starting compounds was detected (Figure 2, Table 1).

Figure 2.

LCMS analysis of glutathione addition to VUF14480 and VUF14481. VUF14480 (top panel) or VUF14481 (bottom panel) were mixed with glutathione in a 1:1 molar ratio and incubated overnight at 22°C. The incubated mixtures were subsequently separated and analysed by LCMS. (Top panel) Reaction product (588 g·mol−1; m+1) was formed that corresponded to the mass of VUF14480 (280 g·mol−1) and glutathione (307 g·mol−1). Peak with mass 295 g·mol−1 (m+2/2) corresponded to a double protonated product. (Bottom panel) VUF14481 (269 g·mol−1; m+1) and glutathione (307 g·mol−1; GSSG m+2/2) could only be detected separately and no product was formed.

Table 1.

| Compound | Retention time (min) | Observed mass (g·mol−1) | Expected mass (g·mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VUF14480 | 2.57–2.68 | 281 | 281 |

| VUF14481 | 1.56–1.77 | 269 | 269 |

| Glutathione | 307 | ||

| Cysteine ethyl ester | 149 | ||

| VUF14480 + glutathione | 1.98–2.12 | 588/295 | 588 |

| VUF14481 + glutathione | 1.51–1.72/1.11–1.24 | 269/307 | 269/307 |

| VUF14480 + cysteine ethyl ester | 2.24–2.40 | 430/216/281 | 430 |

| VUF14481 + cysteine ethyl ester | 1.53–1.76 | 269 | 269/149 |

Determination of the affinity of compounds VUF14480 and VUF14481 for the hH4 receptor

To determine their binding affinity for the hH4 receptor, both compounds were tested in a heterologous [3H]-histamine displacement experiment (n = 3). VUF14480 and VUF14481 had comparable binding affinities for the hH4 receptor in the low micromolar range (pKi = 6.3 ± 0.1 and pKi = 6.5 ± 0.1, respectively; Table 2, Figure 1A). Importantly, it should be noted that the pKi value of the possible covalent binder VUF14480 is not a true pKi value due to the absence of equilibrium binding between both competing ligands and receptor.

Table 2.

| pKi (M) | pEC50 ([35S]-GTPγS) (M) | Emax ([35S]-GTPγS) (% of HA) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Bmax (pmol·mg−1) | Kd (nM) | HA | VUF14481 | VUF14480* | HA | VUF14481 | VUF14480 | HA | VUF14481 | VUF14480 |

| hH4-WT receptor | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 7 ± 1 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | (6.3 ± 0.1) | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 100 ± 4 | 49 ± 5 | 59 ± 8 |

| hH4-C983.36S receptor | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 27 ± 6 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | (5.8 ± 0.1) | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 100 ± 6 | 46 ± 7 | 32 ± 5 |

Bmax and Kd values were obtained via a [3H]-histamine saturation-binding experiment and pKi values* were determined via a heterologous displacement binding experiment on crude membrane fractions of HEK293T cells expressing hH4 receptors. Data shown are average ± SEM values from at least three experiments performed in triplicate.

Functional characterization of VUF14480 and VUF14481

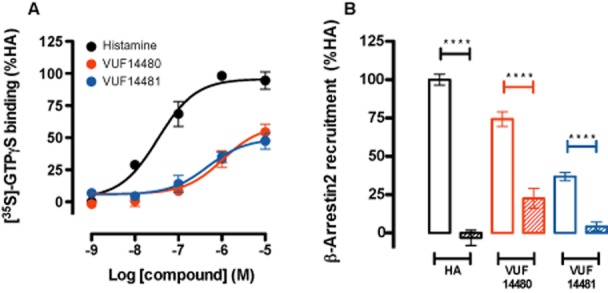

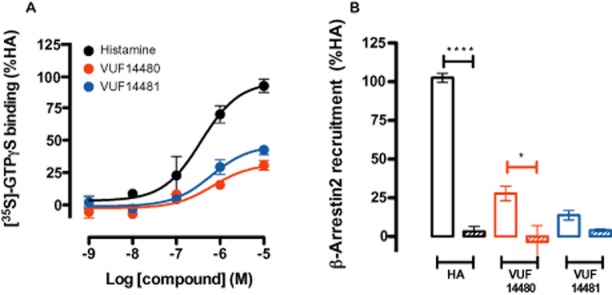

Functional characterization of these compounds in a GTPγS-binding assay on hH4 receptor-expressing membranes (n = 3) showed that VUF14480 is a partial agonist (Emax = 60 ± 8%) in comparison to histamine (Emax = 100 ± 4%, pEC50 = 7.5 ± 0.2). The potency of compound VUF14480 (pEC50 = 6.0 ± 0.2) was comparable to its affinity (pKi = 6.3 ± 0.1; Figure 3A, Table 2). In addition, VUF14481 was also identified as a partial hH4 receptor agonist (Emax = 49 ± 5%) with a potency (pEC50 = 6.3 ± 0.2) that corresponded to its affinity (pKi = 6.4 ± 0.1; Figure 3A, Table 2). Moreover, both VUF14481 and VUF14480 induced β-arrestin2 recruitment to the hH4 receptor, as evaluated in a BRET-based assay (n = 3) that could be inhibited by pre-incubation with the H3/H4 receptor antagonist thioperamide (Figure 3B). Interestingly, β-arrestin2 recruitment upon VUF14480 stimulation could not be completely blocked by thioperamide; this might be due to a possible covalent, non-displaceable interaction of VUF14480 with the hH4 receptor.

Figure 3.

Functional characterization of VUF14480 and VUF14481. (A) GTPγS-binding assay. Membranes (10 μg per well) from cells expressing hH4 receptors were incubated with increasing amounts (1 nM–10 μM) of histamine, VUF14480 or VUF14481 for 1 h at 22°C. (B) BRET-based β-arrestin2 recruitment assay. Cells expressing the hH4 receptor-Rluc8 and β-arrestin2-mVenus were incubated with 10 μM histamine (HA), VUF14480 or VUF14481 in absence (open columns) and presence (hatched columns) of thioperamide (10 μM) for 20 min at 37°C. Results shown are from at least three pooled experiments performed in triplicate. Data were normalized to the histamine response (100%) and fitted to a three-parameter response model. Error bars indicate SEM values.

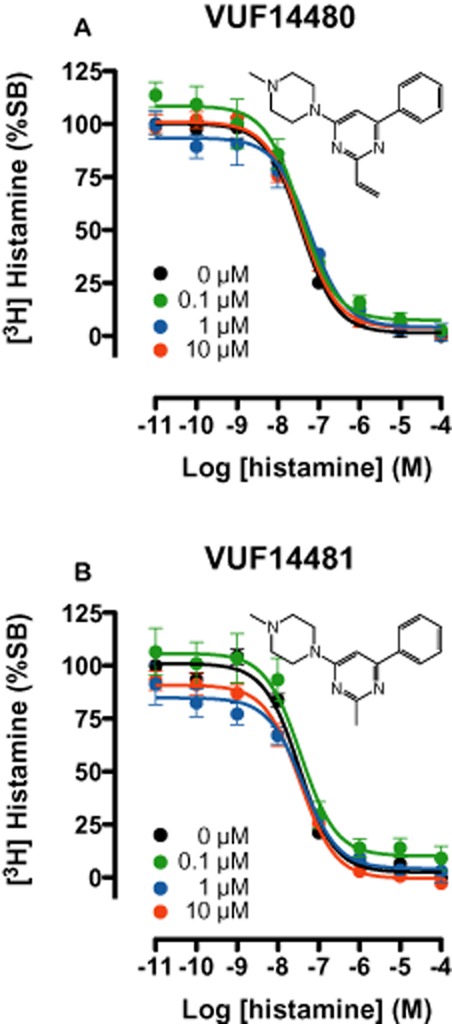

Investigating the covalent interaction of compound VUF14480 with hH4 receptors

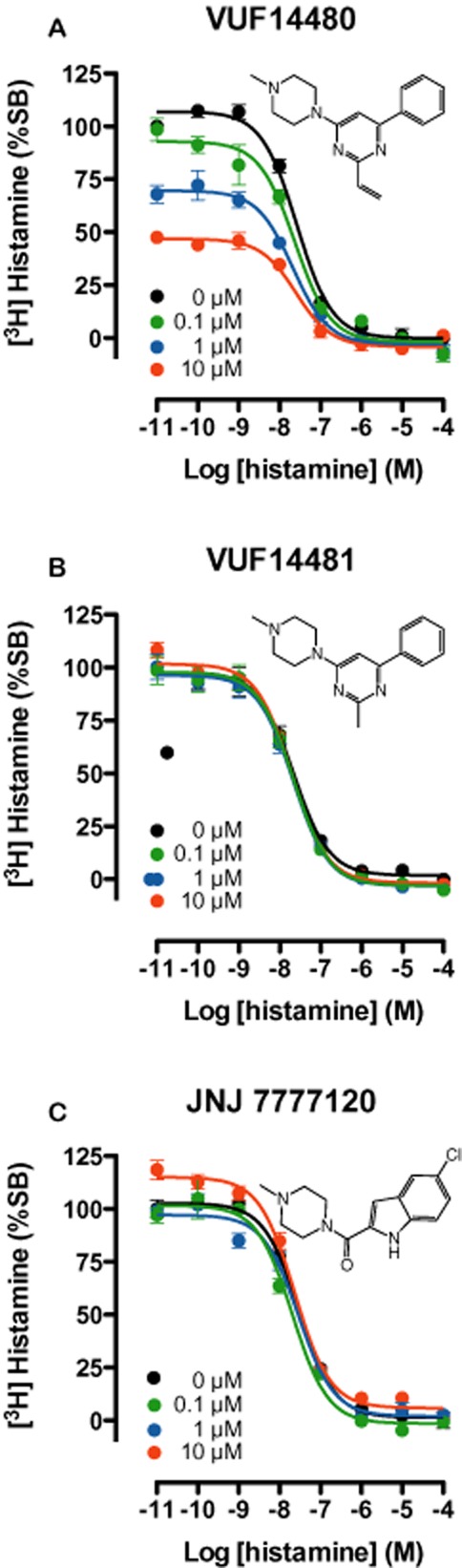

Identification of both compounds as partial hH4 receptor agonists prompted us to investigate the irreversible characteristics of compound VUF14480 by determining its ability to irreversibly block [3H]-histamine hH4 receptor-binding sites. To this end, crude membrane fractions of HEK293T cells, expressing the hH4 receptor, were pre-incubated for 1 h with increasing concentrations (100 nM–10 μM) of VUF14480, VUF14481 or the selective H4 receptor ligand JNJ 7777120. Pretreated membrane fractions were then washed very extensively to ensure dissociation of compounds that were not covalently bound. Pretreatment with VUF14480 resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease (5–50%) in specific [3H]-histamine binding. However, the affinity of histamine for the hH4 receptor was not affected by VUF14480 pretreatment (Figure 4A). In contrast, membrane fractions pretreated with VUF14481 (Figure 4B) or JNJ 7777120 (Figure 4C) showed no decrease in specific [3H]-histamine binding, ensuring the efficiency of the washing procedure, even for JNJ 7777120, which has a long residence time.

Figure 4.

[3H]-histamine binding to hH4 receptor-expressing HEK293T cell membranes pre-incubated with compounds VUF14481, VUF14480 or JNJ7777120. Crude membrane fractions of hH4 receptor-transfected cells were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of VUF14480, VUF14481 or JNJ7777120, at 22°C for 1 h. Pretreated membranes fractions were washed at least three times very extensively with 50 mM Tris-HCl before further incubation at 22°C for 1 h with ∼10 nM [3H]-histamine and increasing amounts (10 pM–10 μM) of non-labelled histamine. Curves are fitted to a one-site competition-binding model. Data shown are pooled data from three experiments performed in triplicate, error bars indicate SEM values.

C983.36 as an anchor point for the covalent bond

Although the above-mentioned binding experiment indicates VUF14480 has a covalent interaction of with hH4 receptors, it does not confirm the hypothesized interaction with the C983.36 residue. We therefore mutated the C983.36 residue into a serine residue. [3H]-histamine bound with a ∼4-fold lower affinity to HEK293T membranes expressing hH4-C983.36S receptor as compared to hH4-WT receptors (i.e. Kd = 27 ± 6 nM and Kd = 7 ± 1 nM, respectively) as measured in equilibrium saturation-binding experiments (n = 3, data not shown). Protein expression levels of hH4-C983.36S receptors and hH4-WT receptors were comparable, with Bmax values of 1.3 ± 0.2 and 1.3 ± 0.1 pmol·mg−1 protein respectively. Affinities of VUF14481 and VUF14480 for the hH4-C983.36S receptor mutant were determined in a heterologous [3H]-histamine displacement binding experiment. VUF14481 had an affinity (pKi 6.8 ± 0.2) for hH4-C983.36S receptors, which was not significantly higher (P > 0.05) than that observed for the hH4-WT receptors (pKi = 6.4 ± 0.1). In contrast, VUF14480 had an affinity (pKi 5.8 ± 0.1) for hH4-C983.36S receptors, which was slightly lower, but not significantly (P > 0.05) different from its affinity for hH4-WT receptors (pKi 6.3 ± 0.1). Efficacy (Emax) values for VUF14481 did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) for hH4-C983.36S receptors (46 ± 7%) and hH4-WT receptors (49 ± 5%; Figures 3A and 5A). In contrast, a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in Emax was observed for the effects of VUF14480 on hH4-C983.36S receptors (32 ± 5%) compared to hH4-WT receptors (59 ± 8%). Potency values of VUF14481 (pEC50 = 6.2 ± 0.2) and VUF14480 (pEC50 = 6.2 ± 0.3) to induce G protein activity were comparable to their respective affinities (pKi = 6.8 ± 0.2 and pKi = 5.8 ± 0.1) for this mutant. Although the possible covalent interaction between C983.36 and VUF14480 did not appear to contribute to binding affinity to the receptor and consequently potency of the compound, this bond seemed to stabilize an active hH4 receptor conformation. Histamine showed a decreased potency (pEC50 = 6.4 ± 0.2) compared to its affinity (pKi = 7.2 ± 0.1) for the hH4-C983.36S receptor (Figure 5A). In contrast, only a minor decrease in potency (pEC50 = 7.5 ± 0.2) was observed for histamine at the hH4-WT receptor (pKi = 8.1 ± 0.1). A BRET-based β-arrestin2 recruitment assay (n = 3) revealed that histamine, VUF14481 and VUF14480 all induced β-arrestin2 recruitment via the hH4-C983.36S receptor (Figure 5B), which was less pronounced for VUF14480 and VUF14481 than that observed via the hH4-WT receptor. Interestingly, complete inhibition of VUF14480-induced β-arrestin2 recruitment via hH4-C983.36S receptors by the H3/H4 receptor antagonist thioperamide (Figure 3B) but not that induced via the hH4-WT receptor (Figure 5B), confirmed the hypothesized covalent interaction between VUF14480 and C983.36.

Figure 5.

Functional characterization of VUF14480 and VUF14481 on hH4-C983.36S receptor. (A) GTPγS-binding assay. Membranes (10 μg per well) from cells expressing hH4 receptor-C983.36S were incubated with increasing amounts (1 nM–10 μM) of histamine, VUF14480 or VUF14481 for 1 h at 22°C. (B) BRET-based β-arrestin2 recruitment assay. Cells expressing the hH4 receptor-C983.36S-Rluc8 and β-arrestin2-mVenus were incubated with 10 μM histamine (HA), VUF14480 or VUF14481 in the absence (open columns) and presence (hatched columns) of thioperamide (10 μM) for 20 min at 37°C. Results shown are from at least three pooled experiments performed in triplicate. Data were normalized to the histamine response (100%) and fitted to a three-parameter response model. Error bars indicate SEM values.

Next, the hH4-C983.36S receptor mutant was tested in a similar pre-incubation binding experiment as conducted for the hH4-WT receptor to test if VUF14480 was able to decrease total [3H]-histamine binding. Pre-incubation of membrane fractions expressing hH4-C983.36S receptors with either VUF14480 (Figure 6A) or VUF14481 (Figure 6B) followed by extensive washing to remove non-covalently bound ligands, did not decrease the specific [3H]-histamine binding.

Figure 6.

[3H]-histamine binding to hH4-C983.36S receptor expressing HEK293T cell membranes pre-incubated with VUF14480 or VUF14481. Crude membrane fractions of hH4-C983.36S receptor transfected cells were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of VUF14480 or VUF14481 at 22°C for 1 h. Pretreated membranes were subsequently washed extensively and at least three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl before further incubation at 22°C for 1 h with ∼10 nM [3H]-histamine and increasing amounts (10 pM–10 μM) of non-labelled histamine. Curves are fitted to a one-site competition-binding model. Data shown are pooled data from three experiments performed in triplicate, error bars indicate SEM values.

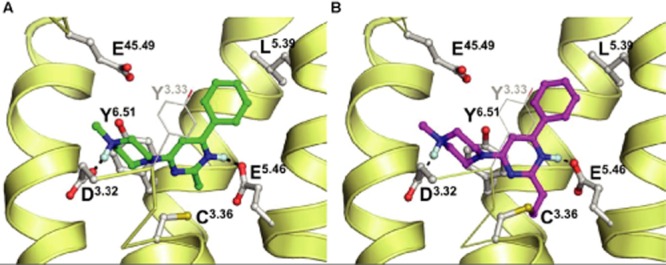

Binding models for VUF14481 and VUF14480 in the hH4 receptor-binding pocket

Binding models for VUF14481 and VUF14480 were constructed based on our previously published 2-aminopyrimidine-binding position in hH4 receptors (Schultes et al., 2013b) and in combination with the newly identified covalent interaction of VUF14480 with C983.36. Whereas VUF14481 binds to the hH4R in a non-covalent manner (Figure 7A), the close proximity of the ethenyl group at position 2 of the pyrimidine scaffold to C983.36 resulted in the formation of a covalent bond between VUF14480 and C983.36 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Proposed binding modes of VUF14481 (A, green) and VUF14480 (B, magenta) in previously validated hH4 receptor homology model (Schultes et al., 2013b). Rendering and colour coding is the same as in Figure 1.

Discussion and conclusion

The interaction between a ligand and GPCRs is in general reversible. However, covalent ligand–GPCR interactions are also observed. For example, retinal binds covalently to rhodopsin via a protonated Schiff base linkage between its aldehyde group and the amino group of K2967.43 (Palczewski et al., 2000), whereas β-funaltrexamine binds covalently to the rat μ opioid receptor (Chen et al., 1995). The use of these compounds as valuable tools for structural research and for identification of accessible amino acids in ligand-binding pockets is widely acknowledged (Javitch et al., 1999; Buck et al., 2005; Potashman and Duggan, 2009; Chapman et al., 2010; Manglik et al., 2012). In this study, we use the covalent interaction to confirm a hypothesized ligand position in the binding pocket.

A detailed binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines in the hH4 receptor-binding pocket has recently been postulated, suggesting a strong interaction between the amino group at position 2 of the pyrimidine and hH4 receptor-E1825.46 (Schultes et al., 2013b). Based on this binding mode, we anticipated that substituents at position 2 of the pyrimidine scaffold are in close proximity to hH4 receptor-C983.36. We therefore proposed that the nucleophilic thiol group of this cysteine is able to form a covalent interaction with an ethenyl group at position 2 of the pyrimidine scaffold of VUF14480, which functions as a Michael acceptor. Indeed, from the results of the LCMS analysis, VUF14480 is able to form a covalent adduct with glutathione or cysteine ethyl ester. In accord with this, the related structural control VUF14481 did not react with glutathione or the cysteine ethyl ester.

Both VUF14480 and VUF14481 were found to bind to the hH4 receptor with submicromolar affinities, which is a 100-fold less than that found previously for 2-aminopyrimidines (Schultes et al., 2013b). This affinity decrease can be explained by the loss of the interaction between a protonated 2-amino group and hH4 receptor-E5.46. In fact, a similar reduction (10- to 100-fold) in affinity for 2-aminopyrimidines was observed when E1825.46 was mutated into a non-charged glutamine residue (Schultes et al., 2013b).

In contrast to previously described 2-aminopyrimidines antagonists (Engelhardt et al., 2009), VUF14481 and VUF14480 partially induced hH4 receptor-mediated G protein activation. The efficacy of VUF14481 and VUF14480 was not only limited to G protein signalling but also extended to the recruitment of β-arrestin2 to hH4 receptors. It was very interesting to observe that only a small replacement of the 2-amino group by a methyl or ethenyl group changed these pyrimidines from being an antagonist (data not shown) into a partial agonist. Interestingly, S1113.36 was previously identified as an important link between histamine binding and conformational changes in helices 6 and 7 of the histamine H1 receptor (Jongejan et al., 2005). Based on in silico-guided mutagenesis studies, S1113.36 was proposed to act as a rotamer toggle switch that, upon agonist binding, initiates the activation of the receptor through N1987.45 (Jongejan et al., 2005).

Functional experiments are the preferred method for identifying covalent antagonists and even weak partial agonists. A covalent antagonist will not only shift a concentration-response curve (depending on receptor reserve) to the right, but more importantly will (eventually) decrease the maximal agonist-induced response by reducing the number of available receptors (Kenakin et al., 2006). Due to the agonist effects of VUF14480, we tested the covalent character of this compound by showing that it had the ability to permanently decrease the number of available histamine-binding sites. Binding experiments are generally not the preferred method for proving covalent binding of a compound to a GPCR, as it is difficult to distinguish irreversible from pseudo-irreversible interactions (Kenakin et al., 2006). To make sure we were not looking at pseudo-irreversible intereactions caused by slow dissociation rates, we also tested the effects of another hH4 receptor ligand, JNJ 7777120, in our experiments. JNJ 7777120 has been reported to have a relatively slow dissociation rate compared to other hH4 receptor compounds tested (Smits et al., 2012). Extensive washing of membranes that had been pre-incubated with JNJ 7777120 resulted in a full recovery of available histamine-binding sites. This proves that extensive washing will result in full dissociation of a compound with a relatively long hH4 receptor residence time. Interestingly, VUF14480, but not VUF14481, concentration-dependently reduced specific [3H]-histamine binding, indicating that VUF14480 irreversibly occupies the hH4 receptor-binding pocket. Similarly, the A1 adenosine receptor antagonist FSCPX has been shown to decrease the binding sites in its receptor in a concentration-dependent manner (Lorenzen et al., 2002).

Based on our 2-aminopyrimidine binding mode of the hH4 receptor, we hypothesized that VUF14480 covalently interacts with C983.36, located in the third transmembrane helix (TM3) of the hH4 receptor-binding site. However, from the pre-incubation experiments, we could not exclude a possible role of other putative surface-accessible cysteine residues in the hH4 receptor. In the hH4 receptor, three cysteine residues are located in the TM helices (i.e. C873.25, C983.36 and C3156.47) and one is located in the extracellular loop (EL)2 (C16445.50). C873.25 is thought to form a disulphide bridge with the cysteine residue in EL2, which leaves C3156.47 and C983.36 as the two possible interaction sites. Interestingly, C3156.47 has been demonstrated to be the site for the covalent bond between human cannabinoid receptor CB2 and the ligand AM841 (Mercier et al., 2010; Szymanski et al., 2011). However, this residue is located outside the proposed binding pocket of the hH4 receptor and might only be accessible to ligands that can enter the GPCR via the lipid bilayer, as has been proposed for AM841 (Hurst et al., 2010). Serine substitution of the hH4 receptor-C983.36 prevented the decrease in [3H]-histamine-binding sites induced by pre-incubation of VUF14480 that was observed with WT hH4 receptors, confirming the role of this residue in the formation of the covalent bond. It is noted that in the dopamine D2 receptor, C1183.36 was identified as a solvent accessible residue pointing into the binding cavity by using methanethiosulfonate reagents (Javitch et al., 1994). Moreover, C3.36 in α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors was shown to covalently interact with the reactive aziridinium derivative of phenoxybenzamine (Frang et al., 2001). Collectively, these data provide substantial evidence that this conserved cysteine residue, present in 24 out of 42 bioamine receptors and 30 out of 369 non-olfactory human GPCRs (Surgand et al., 2006), is accessible for ligands in these amine GPCR families.

In conclusion, the rational design of a covalent hH4 receptor ligand has successfully led to the synthesis and pharmacological identification of VUF14480. This compound is thought to bind covalently to the hH4 receptor-C983.36 residue and partially induce hH4 receptor-mediated G protein activation and β-arrestin2 recruitment. Moreover, our observations confirm the previously proposed binding mode of 2-aminopyrimidines (Schultes et al., 2013b). The possible covalent partial hH4 receptor agonist VUF14480 will be a useful tool to stabilize the receptor into an active confirmation and further investigate the structure of the active hH4 receptor, as recently shown for the agonist FAUC50 that covalently binds to β2-adrenoceptor H2.64C and facilitates GPCR crystallization (Rosenbaum et al., 2011).

Acknowledgments

Herman Lim and Kamar Azijli are acknowledged for making the hH4-C983.36S receptor mutant. Hans Custers is acknowledged for his help with the LCMS experiments. S. N., H. V., C. dG. and R. L. participate in the European COST Action BM0806. C. dG. is sponsored by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research NWO: VENI Grant 700.59.408.

Glossary

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Table S1 Chromatography methods.

References

- Ballesteros JW, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three dimensional models and computational probing of structure funciton relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Buck E, Bourne H, Wells JA. Site-specific disulfide capture of agonist and antagonist peptides on the C5a receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4009–4012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KL, Kinsella GK, Cox A, Donnelly D, Findlay JB. Interactions of the melanocortin-4 receptor with the peptide agonist NDP-MSH. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:433–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez FCM, Edwards JP, Gomez L, Grice CA, Kearney AM, Savall BM, et al. 2008. Benzofuro- and benzothienopyrimidine modulators of the histamine H4 receptor, (Janssen Pharmaceutica NV). WO-2008008359.

- Chen C, Xue JC, Zhu J, Chen YW, Kunapuli S, Kim de Riel J, et al. Characterization of irreversible binding of beta-funaltrexamine to the cloned rat mu opioid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17866–17870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekici OD, Gotz MG, James KE, Li ZZ, Rukamp BJ, Asgian JL, et al. Aza-peptide Michael acceptors: a new class of inhibitors specific for caspases and other clan CD cysteine proteases. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1889–1892. doi: 10.1021/jm049938j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt H, Smits RA, Leurs R, Haaksma E, de Esch IJ. A new generation of anti-histamines: histamine H4 receptor antagonists on their way to the clinic. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12:628–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frang H, Cockcroft V, Karskela T, Scheinin M, Marjamaki A. Phenoxybenzamine binding reveals the helical orientation of the third transmembrane domain of adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31279–31284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garuti L, Roberti M, Bottegoni G. Irreversible protein kinase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:2981–2994. doi: 10.2174/092986711796391705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf C, Foata N, Engkvist O, Rognan D. Molecular modeling of the second extracellular loop of G protein-coupled receptors and its implication on structure-based virtual screening. Proteins. 2008;71:599–620. doi: 10.1002/prot.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Urizar E, Kralikova M, Mobarec JC, Shi L, Filizola M, et al. Dopamine D2 receptors form higher order oligomers at physiological expression levels. EMBO J. 2008;27:2293–2304. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst DP, Grossfield A, Lynch DL, Feller S, Romo TD, Gawrisch K, et al. A lipid pathway for ligand binding is necessary for a cannabinoid G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17954–17964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istyastono EP, de Graaf C, de Esch IJ, Leurs R. Molecular determinants of selective agonist and antagonist binding to the histamine H receptor. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011a;11:661–679. doi: 10.2174/1568026611109060661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istyastono EP, Nijmeijer S, Lim HD, van de Stolpe A, Roumen L, Kooistra AJ, et al. Molecular determinants of ligand binding modes in the histamine H(4) receptor: linking ligand-based three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) models to in silico guided receptor mutagenesis studies. J Med Chem. 2011b;54:8136–8147. doi: 10.1021/jm201042n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonowski JA, Grice CA, Chai W, Dvorak CA, Venable JD, Kwok AK, et al. The first potent and selective non-imidazole human histamine H4 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3957–3960. doi: 10.1021/jm0341047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitch JA, Li X, Kaback J, Karlin A. A cysteine residue in the third membrane-spanning segment of the human D2 dopamine receptor is exposed in the binding-site crevice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10355–10359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitch JA, Ballesteros JA, Chen J, Chiappa V, Simpson MM. Electrostatic and aromatic microdomains within the binding-site crevice of the D2 receptor: contributions of the second membrane-spanning segment. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7961–7968. doi: 10.1021/bi9905314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan A, Bruysters M, Ballesteros JA, Haaksma E, Bakker RA, Pardo L, et al. Linking agonist binding to histamine H1 receptor activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:98–103. doi: 10.1038/nchembio714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan A, Lim HD, Smits RA, de Esch IJ, Haaksma E, Leurs R. Delineation of agonist binding to the human histamine H4 receptor using mutational analysis, homology modeling, and ab initio calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:1455–1463. doi: 10.1021/ci700474a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiorgou O, Patsis G, Pelecanou M, Raptopoulou CP, Terzis A, Siatra-Papastaikoudi T, et al. S)-(2-(2′-Pyridyl)ethyl)cysteamine and (S)-(2-(2′-pyridyl)ethyl)-d,l-homocysteine as ligands for the ‘fac-[M(CO)(3)](+)’ (M = Re, (99m)Tc) core. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:4118–4120. doi: 10.1021/ic050254r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T, Jenkinson S, Watson C. Determining the potency and molecular mechanism of action of insurmountable antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:710–723. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klutchko SR, Zhou H, Winters RT, Tran TP, Bridges AJ, Althaus IW, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. 19. 6-Alkynamides of 4-anilinoquinazolines and 4-anilinopyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidines as irreversible inhibitors of the erbB family of tyrosine kinase receptors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1475–1485. doi: 10.1021/jm050936o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs R, Vischer HF, Wijtmans M, de Esch IJ. En route to new blockbuster anti-histamines: surveying the offspring of the expanding histamine receptor family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HD, de Graaf C, Jiang W, Sadek P, McGovern PM, Istyastono EP, et al. Molecular determinants of ligand binding to H4R species variants. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:734–743. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Dalhus B, Gundersen L-L, Rise F. Addition and cycloaddition to 2- and 8-vinylpurines. Acta Chem Scand. 1999;53:269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen A, Beukers MW, van der Graaf PH, Lang H, van Muijlwijk-Koezen J, de Groote M, et al. Modulation of agonist responses at the A(1) adenosine receptor by an irreversible antagonist, receptor-G protein uncoupling and by the G protein activation state. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:1251–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, et al. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier RW, Pei Y, Pandarinathan L, Janero DR, Zhang J, Makriyannis A. hCB2 ligand-interaction landscape: cysteine residues critical to biarylpyrazole antagonist binding motif and receptor modulation. Chem Biol. 2010;17:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOE. Molecular Operating Environment. Montreal, Canada: Chemical Computing Group Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer S, Leurs R, Smit MJ, Vischer HF. The Epstein-Barr virus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor BILF1 hetero-oligomerizes with human CXCR4, scavenges Galphai proteins, and constitutively impairs CXCR4 functioning. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29632–29641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer S, de Graaf C, Leurs R, Vischer HF. Molecular pharmacology of histamine H4 receptors. Front Biosci. 2012a;17:2089–2106. doi: 10.2741/4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijmeijer S, Vischer HF, Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ, Leurs R. Analysis of multiple histamine H4 receptor compound classes uncovers galphai and beta-arrestin2 biased ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 2012b;82:1174–1182. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Scheerens H, Li SJ, Schultz BE, Sprengeler PA, Burrill LC, et al. Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton's tyrosine kinase. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:58–61. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potashman MH, Duggan ME. Covalent modifiers: an orthogonal approach to drug design. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1231–1246. doi: 10.1021/jm8008597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DM, Zhang C, Lyons JA, Holl R, Aragao D, Arlow DH, et al. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-beta(2) adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ. Agonist-biased signaling at the histamine H4 receptor: JNJ7777120 recruits beta-arrestin without activating G proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:749–757. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander K, Kottke T, Tanrikulu Y, Proschak E, Weizel L, Schneider EH, et al. 2,4-Diaminopyrimidines as histamine H4 receptor ligands–Scaffold optimization and pharmacological characterization. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:7186–7196. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes S, Engelhardt H, Roumen L, Zuiderveld OP, Haaksma EEJ, de Esch IJP, et al. Combining quantum mechanical ligand conformation analysis and protein modeling to elucidate GPCR-ligand binding modes. ChemMedChem. 2013a;8:49–53. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultes S, Nijmeijer S, Engelhardt H, Kooistra AJ, Vischer HF, de Esch IJP, et al. Mapping histamine H4 receptor–ligand binding modes. MedChemComm. 2013b;4:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura T, Shiroishi M, Weyand S, Tsujimoto H, Winter G, Katritch V, et al. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature. 2011;475:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits RA, de Esch IJ, Zuiderveld OP, Broeker J, Sansuk K, Guaita E, et al. Discovery of quinazolines as histamine H4 receptor inverse agonists using a scaffold hopping approach. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7855–7865. doi: 10.1021/jm800876b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits RA, Leurs R, de Esch IJ. Major advances in the development of histamine H4 receptor ligands. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits RA, Adami M, Istyastono EP, Zuiderveld OP, van Dam CM, de Kanter FJ, et al. Synthesis and QSAR of quinazoline sulfonamides as highly potent human histamine H4 receptor inverse agonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2390–2400. doi: 10.1021/jm901379s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits RA, Lim HD, van der Meer T, Kuhne S, Bessembinder K, Zuiderveld OP, et al. Ligand based design of novel histamine H(4) receptor antagonists; fragment optimization and analysis of binding kinetics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgand JS, Rodrigo J, Kellenberger E, Rognan D. A chemogenomic analysis of the transmembrane binding cavity of human G-protein-coupled receptors. Proteins. 2006;62:509–538. doi: 10.1002/prot.20768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DW, Papanastasiou M, Melchior K, Zvonok N, Mercier RW, Janero DR, et al. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics of human cannabinoid receptor 2: covalent cysteine 6.47(257)-ligand interaction affording megagonist receptor activation. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4789–4798. doi: 10.1021/pr2005583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou HR, Overbeek-Klumpers EG, Hallett WA, Reich MF, Floyd MB, Johnson BD, et al. Optimization of 6,7-disubstituted-4-(arylamino)quinoline-3-carbonitriles as orally active, irreversible inhibitors of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 kinase activity. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1107–1131. doi: 10.1021/jm040159c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijtmans M, de Graaf C, de Kloe G, Istyastono EP, Smit J, Lim H, et al. Triazole ligands reveal distinct molecular features that induce histamine H4 receptor affinity and subtly govern H4/H3 subtype selectivity. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1693–1703. doi: 10.1021/jm1013488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.