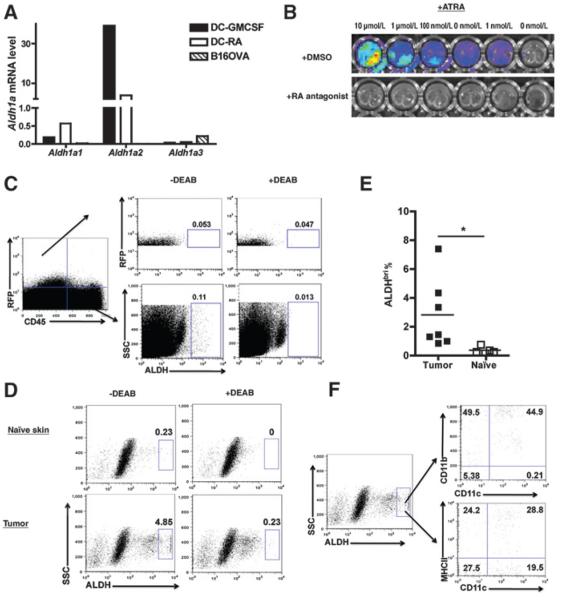

Figure 2.

Analysis of the cellular source of RA in tumor-bearing mice. A, RT-PCR analysis of Aldh1a1, Aldh1a2, and Aldh1a3 expression in DCs and tumor cells. GM-CSF or RA-treated CD11c+ DCs and in vitro cultured B16.OVA tumor cells were analyzed for mRNA expression of Aldh1a1, Aldh1a2, and Aldh1a3. This is representative of 2 experiments. B, lack of constitutive RA reporting in B16.OVA-DR5-Luciferase tumor cells. Representative in vitro imaging of control or RA-treated B16.OVA-DR5-Luciferase cells. RA was used at indicated concentration in culture in the presence of vehicle control (DMSO; top) or Pan-RAR antagonist (bottom). This is representative of 3 experiments with similar results. C, ex vivo analysis of tumor RALDH activity. Skin tissues from naïve mice and tumor tissues of day 5 tumor-bearing mice were analyzed for RALDH activity. Data shown are gated on live cells, and RALDH activity is resolved in the RFP+ CD45− (tumor) and RFP−CD45+ hematopoietic (immune) populations. D, ex vivo analysis of TILs within the TME for expression of RALDH activity. The samples were prepared as in C, but shown data gated on total live cells with tumor cells excluded. E, quantified ALDHbri population in TILs. The frequency of ALDHbri among total live TILs or naïve skin-residential cells was determined. F, phenotypic analysis of ALDHbri populations in TILs. Data shown in C–F are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results (n≥3 mice per group), and data shown in (E) are pooled from 2 experiments (n =6–7 mice per group). Statistically significant differences were determined by t test. SSC, side scatter.