Abstract

The paper examines changes in the relationship between employment and household tasks of Japanese couples, using data drawn from national cross-sectional surveys in 1994, 2000 and 2009 of persons aged 20–49 and from the 2009 follow-up of the 2000 survey. Wives’ employment is structured by their husbands’ employment time and earning power, as well as by their family situations including the presence and age of children and coresidence with parents. Housework hours of husbands, though very low, increased over time, while wives’ hours decreased. Wives housework time decreases as their employment time increases. Marriage dramatically increases women’s housework time but produces little change in men’s time. Husbands’ housework hours are positively correlated with reported marital satisfaction of both spouses.

Using repeated cross-sectional surveys and a longitudinal survey in Japan, we document changes in couples’ time spent on employment and household tasks and the relationship between these, as well as the relationship of wives’ employment with husbands’ housework time, and of wives’ housework time with husbands’ employment time. By examining the complex of relationships in the gender allocation of employment and household tasks, this study helps further our understanding of the changing gender roles in Japan, a post-industrial country with dramatically different cultural heritage from the West.

1. Conceptual Framework

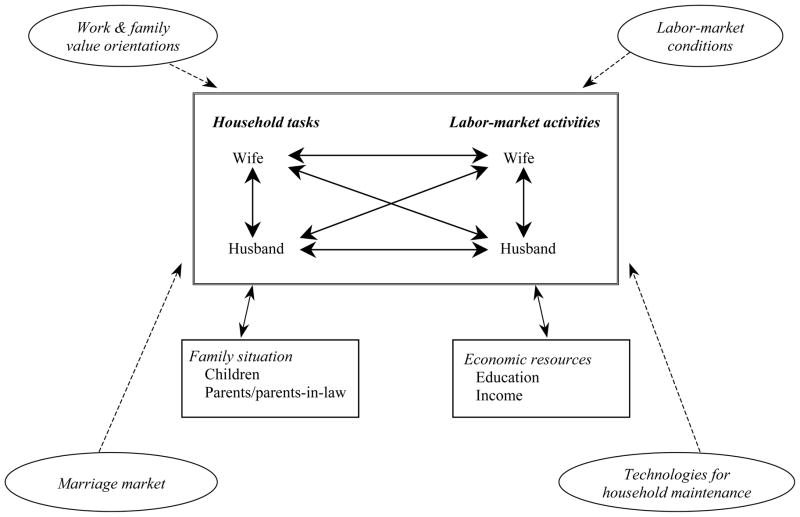

Our analysis is guided by the conceptual framework presented in Figure 1. The main focus is on the time allocation of employment and household tasks of spouses: specifically, the relationships between (1) wives’ employment and their own housework time, (2) husbands’ employment time and their own housework time, (3) spouses’ employment time, (4) spouses’ housework time, (5) wives’ employment and husband’s housework time, and (6) wives’ housework time and husbands’ employment time. Note that arrows run both ways in these complex relationships as each path is likely reciprocal. The two smaller rectangles point to micro factors affecting employment and housework time, and the ovals call attention to elements of the broader context within which the interplay of employment and housework occurs. It is particularly important to note that any of these contextual factors may affect any of the key analytical variables indirectly through the network of relationships represented.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Factors Affecting Time Spent on Household Tasks and Employment

Notes: Ovals represent macro factors and rectangles represent micro factors. A third dimension, not shown here, is time; all elements in the figure are subject to change over time.

2. Data and Measures

We use replicated cross-sectional data drawn from three surveys: the 1994 National Survey of Work and Family Life (NSWFL), and the 2000 and 2009 National Surveys on Family and Economic Conditions (NSFEC). The 1994 NSWFL is a nationally representative sample of 2,447 Japanese men and women aged 20–59 (see Tsuya and Bumpass 2004). The 2000 NSFEC is a national probability sample of 4,482 Japanese men and women aged 20–49 (see Rindfuss et al. 2004). Of these, 2,356 responded to a 2009 follow-up. There were 3,112 respondents to the 2009 NSFEC new cross-section. The same questionnaire was used in the two surveys in 2009. Weights are used for the 2000 and 2009 cross-sections to account for oversampling of ages 20–39 and differential response rates by age, sex and size of place of residence. The 1994 data are restricted to ages 20–49 to match the age limits of the 2000 and 2009 cross-sectional surveys.

In all the surveys, married respondents were asked to provide reports for themselves and for their spouses on objective information, including the hours and schedules of employment, time spent on core household tasks, and basic characteristics such as age and education. This paper focuses on two central dimensions of the gender division of labor: employment time and housework time. Time spent on childcare was not included in the housework time estimates because this variable is difficult to measure since parents are often doing other things while simultaneously watching children (Coltrane 2000; Ferree 1990; Thompson and Walker 1989).

3. Couples’ Employment

Despite the prolonged economic stagnation since the early 1990s, the employment rate and hours of Japanese husbands in their prime working years appear not to have changed much over the 15 years under study. On the average, they work about 50–51 hours per week and around half work 49 hours or more. This long average workweek is an important factor to consider in evaluating gender differences in time spent on housework (Jacobs and Gerson 2004).

Wives’ employment rate increased modestly from around 58 percent in 1994 to 62 percent in 2000, and reached a plateau thereafter, but the mean work hours of employed wives declined from 36 hours per week in 1994 to 34 hours in 2000, and to 32 hours in 2009. This decline was due primarily to increases in the proportion of wives working fewer than 35 hours per week and decreases in the proportion of those working 42 hours or more. Women working less than 35 hours per week are likely to hold temporary employment while those working 42 hours or more are likely to hold regular employment. Hence, the employment circumstances of Japanese wives of reproductive ages appear to have deteriorated—whether by choice or as a consequence of the restructuring of the labor market.

Table 1 presents the percent employed and the mean work hours of employed wives by husbands’ employment hours and income, as well as by age of youngest child and coresidence with parents. Aside from the few husbands who work the unusual schedule of less than 35 hours weekly (who are often ill or older), wives work fewer hours if their husbands work longer hours or have higher income. The relationship with husband’s income becomes stronger over time. In 2009, 67 percent were employed among wives whose husbands made the least, compared to 57 percent of those whose husbands made the most. This is what we would expect as wives likely enter the workforce to help their households financially (Kohara 2010).

Table 1.

Percentages of Wives Employed and Their Mean Employment Hours per Week, by Selected Characteristics: Japan 1994, 2000 and 2009

| Characteristics | % of Wives Employed | Mean Work Hours per Week of Employed Wives | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | (N) | Mean | (N) | Mean | (N) | Mean | (N) | Mean | (N) | Mean | (N) | |

| Husbands’ employment hours | ||||||||||||

| Less than 35 | 45* | (51) | 57* | (135) | 54* | (103) | --a | (23) | 23* | (74) | 28 | (51) |

| 35–48† | 60 | (540) | 67 | (1,080) | 64 | (681) | 34 | (324) | 31 | (706) | 30 | (427) |

| 49 or more | 58 | (633) | 58* | (1,147) | 60 | (849) | 39* | (368) | 36* | (634) | 34* | (494) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Husbands’ income in previous year | ||||||||||||

| Less than 4 million yen† | 64 | (310) | 64 | (758) | 67 | (629) | 39 | (199) | 35 | (480) | 34 | (409) |

| 4–5.99 million yen | 58 | (453) | 62 | (820) | 61* | (541) | 36* | (263) | 34 | (480) | 33 | (315) |

| 6 million yen or more | 54* | (420) | 59* | (685) | 57* | (424) | 34* | (229) | 30* | (388) | 30* | (228) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age of youngest child | ||||||||||||

| 0–2 | 28* | (227) | 30* | (570) | 36* | (454) | 37 | (63) | 33 | (169) | 34* | (166) |

| 3–6 | 52* | (233) | 52* | (503) | 55* | (374) | 35 | (122) | 29* | (268) | 29 | (209) |

| 7–17† | 71 | (540) | 78 | (759) | 75 | (471) | 35 | (381) | 32 | (587) | 29 | (353) |

| No child under age 18 | 66 | (228) | 74 | (532) | 73 | (330) | 37 | (151) | 36* | (392) | 36* | (242) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Living with parents/parents-in-law | ||||||||||||

| No† | 54 | (792) | 57 | (1,604) | 58 | (1,264) | 34 | (431) | 32 | (875) | 31 | (713) |

| Yes | 65* | (434) | 72* | (741) | 73* | (375) | 39* | (284) | 36* | (522) | 34* | (264) |

Notes: The percentages and the means are weighted for 2000 and 2009, but unweighted for 1994; the number of cases are all unweighted.

Mean is not shown due to a small number of cases (<50).

Statistical significance of the association of wives’ employment rate and hours with selected characteristics is estimated using the logistic or OLS regression models where each characteristic is the only predictor variable. A “*” indicates significance at 5-percent level. A “†” indicates the reference category.

As expected, wives’ employment is strongly affected by their family circumstances. By 2009, the proportion employed ranged from a low of 36 percent among mothers of children under age 3 to 75 percent among those with school-age children. At the same time, it is notable that the employment of mothers of children under age 3 is as high as it is, and that it increased substantially (from 28 to 36 percent) over the 15 years under study. Work hours of employed wives are not as clearly related to ages of children, though those with no children under age 18 have longer workweeks. Perhaps reflecting the availability of childcare, mothers are much more likely to be employed if they are coresiding with parents (73 versus 58 percent in 2009) and also work significantly longer hours.

4. Couples’ Housework Time and Combined Workload

The upper panel of Table 2 presents the mean hours that wives and husbands spent each week on household tasks and husbands’ average share of couples’ task hours in 1994, 2000 and 2009. As expected, there is a very large gender difference in the hours spouses spend on housework at all three time points. While wives spent roughly 30 hours per week on household tasks, husbands spent only 2 to 3 hours on such tasks. Even though women universally spend more time on housework than men (Geist and Cohen 2011; Gershuny 2000), the Japanese difference is extreme.

Table 2.

Mean Housework Hours per Week of Wives and Husbands and Their Average Combined Workload (Hours on Housework and Employment Combined): Japan 1994, 2000 and 2009

| 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Housework Hoursa | |||

| Wives’ hours per week | 33* | 29 | 27* |

| Husbands’ hours per week | 2* | 3 | 3* |

| Husbands’ share (%) | 7* | 9 | 12* |

|

| |||

| % of husbands with no housework | 42* | 30 | 22* |

|

| |||

| Combined Workloadb | |||

| All couples | |||

| Wives’ hours per week | 54* | 49 | 47* |

| Husbands’ hours per week | 53* | 52 | 53 |

| Husbands’ share (%) | 51* | 53 | 54* |

|

| |||

| Dual-earner couples only | |||

| Wives’ hours per week | 66* | 59 | 57* |

| Husbands’ hours per week | 54* | 52 | 54* |

| Husbands’ share (%) | 45* | 48 | 49* |

Notes: Mean hours and percentages are weighted for 2000 and 2009, but unweighted for 1994.

Computed by adding the time devoted to cleaning house, doing laundry, cooking, cleaning after meals, and grocery shopping. Housework hours exclude time spent on childcare.

Computed by adding hours spent on housework and on employment.

Statistical significance of change over time in spouses’ housework hours and combined workload is estimated using the OLS or logistic regression models where time is the only predictor variable. Year 2000 is the reference category, and a “*” indicates significance at 5-percent level.

At the same time, we also see signs of modest change in the gender difference in housework time. Wives’ average housework time declined substantially from around 33 hours per week in 1994 to 27 hours in 2009, while the corresponding time for husbands increased from 2 to 3 hours. Consequently, husbands’ share in couples’ housework time increased from 7 percent to 12 percent. These changes are as expected and all in the direction of gender balance, but the level of husbands’ housework time nonetheless remains low and the absolute amount of increase in husbands’ contributions is very small. Therefore, the increase in husbands’ share of household tasks is primarily due to wives’ reduction in their housework time, rather than to increases in husbands’ contributions. We also examined changes in spouses’ hours and husbands’ share in each core task and found that they followed the same trends as those in the total task hours.

There was, however, a sizable decline in the proportion of husbands who do no housework: from 42 percent in 1994 to 22 percent in 2009. Japanese husbands seem to be increasingly drawn into the domestic arena traditionally considered as female, crossing the symbolic gender barrier associated with doing housework.

Not surprisingly, similar to Western countries (Geist 2010), Japanese spouses differ in the reported hours that husbands spend doing housework. There is remarkable agreement with respect to the average hours wives work around the house (less than an hour difference), but considerable disagreement about whether husbands do any housework at all: in 2009, 25 percent of wives said their husbands did no housework, compared to the 18 percent reported by husbands. A small effort on the part of a husband may seem important to him in light of traditional expectations, but may be regarded as no help at all from the perspective of his wife. Nonetheless, both wives and husbands report a substantial decline between 1994 and 2009 in the proportions of husbands doing no housework. The truth may well lie in between the reports of both spouses, but the average is low enough that the difference matters rather little.

As shown in the lower panel of Table 2, when housework and employment hours are considered jointly, the large gender inequality we saw in the division of household labor disappears, and the gender balance becomes slightly more favorable toward wives: husband’s average share of the combined workload increases from 51 percent in 1994 to 54 percent in 2009. When we limit our analysis to dual-earner couples, however, the gender division of combined workload remains unfavorable toward women, although the gender gap has narrowed.

5. Couples’ Employment and Housework Time

In all three study years, the average number of hours that wives spent doing housework was sharply higher among those who were not employed compared to those who were working full-time (31 versus 21 hours in 2009) (see Table 3). Even though wives reduce their own housework hours as their employment time increases, the amount of reduction does not come close to matching the corresponding increase in their employment hours. Consequently, wives’ hours in housework and employment combined rise dramatically as their labor-market time goes up, reflecting the “second shift” of wives employed full-time (Hochschild 1991). While mean differences in housework hours between non-employed wives and those employed full-time are large, husbands’ housework time increases only modestly (by 1–2 hours per week) when their wives are employed full-time.

Table 3.

Mean Hours per Week Spent by Spouses on Housework, and Husbands’ Average Share (%) of Couples’ Housework Hours, by Selected Characteristics: Japan 1994, 2000 and 2009

| Characteristics | Wives’ housework hours | Husbands’ housework hours | Husbands’ share (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | |

| Wives’ employment hours | |||||||||

| 0 (not working)† | 37 | 33 | 31 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 10 |

| 1–34 (part-time) | 34* | 29* | 26* | 2 | 2* | 3 | 5 | 8 | 11 |

| 35+ (full time) | 27* | 22* | 21* | 3* | 4* | 5* | 12* | 15* | 18* |

|

| |||||||||

| Husbands’ employment hours | |||||||||

| Less than 35 | 35 | 28 | 22* | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 16* |

| 35–48† | 32 | 27 | 26 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 14 |

| 49 or more | 34* | 30* | 28* | 2* | 2* | 3* | 6* | 9* | 11* |

|

| |||||||||

| Husbands’ income | |||||||||

| Less than 4 million yen† | 31 | 28 | 26 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 13 |

| 4–5.99 million yen | 34* | 28 | 28* | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7* | 10 | 12 |

| 6 million yen or more | 34* | 30 | 30* | 2* | 2* | 3 | 6* | 8* | 10* |

|

| |||||||||

| Age of youngest child | |||||||||

| 0–2 | 36* | 31* | 29 | 3* | 3* | 3 | 7 | 10* | 12 |

| 3–6 | 34 | 31* | 28 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 10 |

| 7–17† | 33 | 29 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 11 |

| No child under age 18 | 30* | 26* | 24* | 3* | 3* | 4 | 9* | 11* | 15* |

|

| |||||||||

| Coresidence with parents | |||||||||

| No | 34 | 29 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 13 |

| Yes | 32* | 28 | 25* | 2* | 2* | 2* | 6* | 8* | 10* |

Notes: Means are weighted for 2000 and 2009, but unweighted for 1994.

Statistical significance of the association of spouses’ task time/husbands’ share and selected characteristics is estimated using simple OLS regression models where each characteristic is the only predictor variable. A “*” indicates significance at 5-percent level. A “†” indicates the reference category.

The main story in Table 3 is the strong, though expected, negative relationship between wives’ time spent in employment and housework. Nonetheless, two other patterns also stand out. Wives spend more time on housework, the longer their husbands’ workweek, and in particular, the more husbands earn. Surprisingly, there is relatively little variation by age of the youngest child, though those with no children under age 18 spend less time on housework than those with younger children. As noted, direct childcare time is not reflected in these estimates and this would considerably increase the domestic workload of those with preschool children. At the same time, it is impressive that housework time decreased markedly during the study period even among those with children under age 3. Coresidence with parents reduces housework time of both spouses in all three study years but the degree of reduction tends to be higher for husbands, thereby lowering husbands’ share in couples’ housework time.

The 2009 follow-up allows us to see changes in housework time associated with moving into and out of levels of wives’ employment—not working, employed part-time, or full-time—from 2000 to 2009, and the results are both substantial and as predicted. Women who were at the same level of employment in 2000 and 2009 reported essentially the same number of housework hours in both years, whereas housework hours tended to decrease for those who moved up in their employment levels and increase for those who moved down. Among those who were not employed in 2000, their average weekly housework time increased by 5 hours if they were employed part-time in 2009, and by 8 hours if they were employed full-time in 2009. Among those employed part-time in 2000, their mean housework hours increased by 4 hours if they stopped working by 2009, but decreased by 3 hours if they moved up to full-time employment. Finally, those working full-time in 2000 reduced their housework time by 4 hours per week if they were employed part-time or not at all in 2009.

6. Marriage and Gendered Housework Time

Young Japanese primarily live with their parents when they are unmarried, and the transition to marriage has very different implications for men and women. Compared to 8 hours on housework per week among never-married women in 2009, the corresponding hours are 27 among currently married women (see Table 4). The difference in the distribution of hours is dramatic: in 2009 only 8 percent of never-married women did more than 20 hours of housework per week, compared to 72 percent of married women. Men report only 3–4 hours per week whether or not they are married. By marrying, Japanese women change their position from a receiver of care within household to the primary provider of domestic tasks. Meanwhile, Japanese men remain largely receivers of care with the main provider switching from their mothers to their wives.

Table 4.

Percentage Distribution of Housework Hours per Week of Never-Married and Currently Married Women and Men Age 20–49: Japan 1994, 2000, and 2009

| 1994 | 2000 | 2009 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Never-married | Currently married | Never-married | Currently married | Never-married | Currently married | |

| Women’s housework hours | ||||||

| 0–4 | 32 | 1 | 49 | 4 | 47 | 2 |

| 5–9 | 32 | 2 | 25 | 7 | 21 | 6 |

| 10–19 | 20 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 24 | 20 |

| 20–29 | 10 | 26 | 5 | 26 | 5 | 33 |

| 30 or more | 6 | 59 | 5 | 48 | 3 | 39 |

| Totala | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean hours per week | 10 | 33 | 8 | 29 | 8 | 27 |

| (Number of cases) | (210) | (631) | (875) | (1,046) | (602) | (931) |

| Men’s housework hrs | ||||||

| Zero | 44 | 36 | 34 | 23 | 25 | 18 |

| 1–4 | 32 | 47 | 44 | 54 | 46 | 57 |

| 5–9 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 16 | 15 |

| 10+ | 9 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 10 |

| Totala | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean hours per week | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| (Number of cases) | (232) | (595) | (960) | (1,051) | (667) | (723) |

Notes: Based on self-reporting. Percentages and mean hours are weighted for 2000 and 2009, but unweighted for 1994. The number of cases are unweighted for all three years.

Total may not sum to 100 because of rounding errors.

Using the 2009 cross-sectional data, we examined the Spearman rank-order correlations between housework time and (a) reported marital happiness, and (b) satisfaction with the division of household labor. We found that the more time the husband spent on housework, the happier both spouses were with the marriage, with the correlation stronger for wives’ reports than for husbands’ reports. Men and women differed, however, on their satisfaction with the division of household labor relative to the time the husband spent on housework: the more husbands did, the less satisfied they were with the division of household labor, while wives were more satisfied with the household-task allocation. While the relationship between men’s participation in housework and marital happiness is certainly reciprocal, these patterns suggest that when marriages are happy, men are more likely to comply with their wife’s wishes about housework, even if they do not want to. Hence, happier marriages have greater participation by husbands, but because these husbands are helping more at home, they are less satisfied with the domestic-task allocation.

Conclusion

In summary, there have been increases in the proportion of Japanese wives working but decreases in the hours they work. Husbands work very long hours—a mean of around 50 hours per week. Wives’ employment decreases with their husbands’ employment hours and income, and increases with age of youngest child and coresidence with parents. Between 1994 and 2009, wives have reduced their housework hours substantially, and more husbands are doing at least some housework. Nonetheless, husbands’ average housework time increased by only about one hour per week. The amount of time Japanese husbands spend on housework is still very small, and they are clearly an outlier in comparison to their Western counterparts (Fuwa 2004). The time wives spend doing housework varies markedly with their level of employment. Further, when Japanese women marry, their housework hours increase dramatically. For men, in contrast, marriage produces very little change in their housework time, with the main provider of housework changing from their mothers to their wives. And finally, there is a positive correlation between husbands’ housework time and reported marital satisfaction of both wives and husbands.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Lucie Schmidt, information on work hours based on the Japanese wage structure surveys from Yoshio Okunishi, and the assistance from Emi Tamaki and Gayle Yamashita in data analyses and data file constructions. The 1994 National Survey on Work and Family Life in Japan was funded by the University Research Center at Nihon University. The 2000 National Survey on Family and Economic Conditions was funded by the COE Program “Asian Financial Crisis and Its Microeconomic Responses” at Keio University, and also by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (11CE2002) from Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. The 2009 National Surveys on Family and Economic Conditions were funded by a grant from NICHD to the East-West Center (5R01HD042474), in collaboration with the Global COE Program “Raising Market Quality and Integrated Design of Market Infrastructure” at Keio University. The analyses reported here are also supported by the above NICHD grant.

Contributor Information

Noriko O. Tsuya, Email: tsuya@econ.keio.ac.jp, Department of Economics, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan, (phone) 81–(0)3–5427–1365, (fax) 81–(0)3–5427–1578

Larry L. Bumpass, Email: bumpass@ssc.wisc.edu, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.A

Minja Kim Choe, Email: mchoe@hawaii.edu, East-West Center Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A.

Ronald R. Rindfuss, Email: ron_rindfuss@unc.edu, East-West Center and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A

References

- Coltrane S. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1208–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree MM. Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:866–884. [Google Scholar]

- Fuwa M. Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(6):751–767. [Google Scholar]

- Geist C. Men’s and women’s reports about housework. In: Treas J, Drobnic S, editors. Dividing the domestic: Men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2010. pp. 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Geist C, Cohen PM. Headed toward equality? Housework change in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2011;73:832–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershuny J. Changing times: Work and leisure in postindustrial society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. The second shift. New York: Penguin; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JA, Gerson K. The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kohara M. The response of Japanese wives’ labor supply to husbands’ job loss. Journal of Population Economics. 2010;23:1133–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Choe MK, Bumpass LL, Tsuya NO. Social networks and family change in Japan. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(6):838–861. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Walker AJ. Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:845–871. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuya NO, Bumpass LL. Introduction. In: Tsuya NO, Bumpass LL, editors. Marriage, work, and family life in comparative perspective: Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 2004. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]