Abstract

Background and purpose

Even small differences in design variables for the femoral stem may influence the outcome of a hip arthroplasty. We performed a risk factor analysis for aseptic loosening of 4 different versions of cemented Müller-type straight stems with special emphasis on design modifications (2 shapes, MSS or SL, and 2 materials, CoNiCrMo (Co) or Ti-6Al-7Nb (Ti)).

Methods

We investigated 828 total hip replacements, which were followed prospectively in our in-house register. All stems were operated in the same setup, using Sulfix-6 bone cement and a second-generation cementing technique. Demographic and design-specific risk factors were analyzed using an adjusted Cox regression model.

Results

The 4 versions showed marked differences in 15-year stem survival with aseptic loosening as the endpoint: 94% (95% CI: 89–99) for MSS Co, 83% (CI: 75–91) for SL Co, 81% (CI: 76–87) for MSS Ti and 63% (CI: 56–71) for SL Ti. Cox regression analysis showed a relative risk (RR) for aseptic loosening of 3 (CI: 2–5) for stems made of Ti and of 2 (CI: 1–2) for the SL design. The RR for aseptic stem loosening increased to 8 (CI: 4–15) when comparing the most and the least successful designs (MSS Co and SL Ti).

Interpretation

Cemented Müller-type straight stems should be MSS-shaped and made of a material with high flexural strength (e.g. cobalt-chrome). The surface finish should be polished (Ra < 0.4 µm). These technical aspects combined with modern cementing techniques would improve the survival of Müller-type straight stems. This may be true for all types of cemented stems.

The long-term success of cemented hip stems depends on the longevity of the cement-bone interface and the cement-prosthesis interface (Howell et al. 2004, Scheerlinck and Casteleyn 2006). The quality of the cement-bone interface is influenced by 2 factors: bone quality and cementing technique. The latter includes several factors that influence cement quality. The cement-prosthesis interface is also influenced by the cementing technique, and also by the surface finish, shape, and material stiffness of the prosthesis. Even minimal changes in the design concept may have a major effect on the long-term survival of the stem (Howie et al. 1998, Ellison et al. 2012, Hallan et al. 2012).

Various design concepts (e.g. force-closed and shape-closed) for the fixation of cemented total hip arthroplasties have been put forward (Scheerlinck and Casteleyn 2006). All of them have shown reliable long-term survival (Fowler et al. 1988, Howie et al. 1998, Herberts and Malchau 2000, Morscher et al. 2005, Buckwalter et al. 2006, Hamadouche et al. 2008, Clauss et al. 2009). The Müller straight stem (MSS; Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) was designed according to the shape-closed concept in order to achieve a press-fit fixation in the anterior-posterior plane with a self-centering effect (Clauss et al. 2010). The original MSS was made out of forged CoNiCrMo (Co). The material was changed to Ti-6Al-7Nb (Ti) and the surface was roughened to improve the strength of the cement-prosthesis interface. Following this rationale, the design was changed to a triple taper with even more proximal roughness of the stem (SL Ti). Due to the availability of modular heads, the standard and lateralized offset was abandoned and an intermediate offset introduced in the SL design. Because of poor early results with both titanium stems (Maurer et al. 2001), the SL design was modified to the SL Co version.

We analyzed potential risk factors for aseptic loosening with special emphasis on the effect of design modifications (shape, material stiffness, and surface finish) on long-term survival of cemented Müller-type straight stems.

Patients and methods

Between 1984 and 1996, 828 total hip replacements were operated with cemented Müller-type straight stems at our institution (Table 1). The patients had a clinical and radiographic follow-up after 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 years. After 5 years of follow-up, survival analysis showed inferior results for Ti stems with the SL design compared to the Co stems with the MSS design (Schweizer et al. 2005). Analyzing the Ti stems after 10 years, Maurer et al. (2001) found male sex, age of < 65 years, a small stem, and the SL design to be risk factors for aseptic loosening.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| MSS Co | MSS Ti | SL Ti | SL Co | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 172 (21) | 267 (32) | 233 (28) | 156 (19) |

| Implantation period | 07/1984– | 07/1987– | 11/1990– | 11/1993– |

| 07/1987 | 11/1990 | 11/1993 | 07/1995 | |

| Follow-up, years (SD) | 13.7 (7.5) | 13.2 (6.5) | 11.8 (5.5) | 11.6 (5.0) |

| Age, years (SD) | 69.1 (9.7) | 69.2 (9.3) | 69.6 (9.6) | 67.8 (10.1) |

| Males, n (%) | 94 (55) | 144 (54) | 148 (64) | 99 (64) |

| Right hip, n (%) | 100 (58) | 148 (55) | 120 (52) | 83 (53) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Osteoarthritis, n (%) | 135 (79) | 224 (84) | 207 (89) | 134 (86) |

| IA, n (%) | 9 (5) | 11 (4) | 5 (2) | 5 (3) |

| Fx, n (%) | 17 (10) | 21 (8) | 12 (5) | 5 (3) |

| Other, n (%) | 11 (6) | 11 (4) | 9 (4) | 12 (8) |

IA: inflammatory arthritis; Fx: femoral neck fracture.

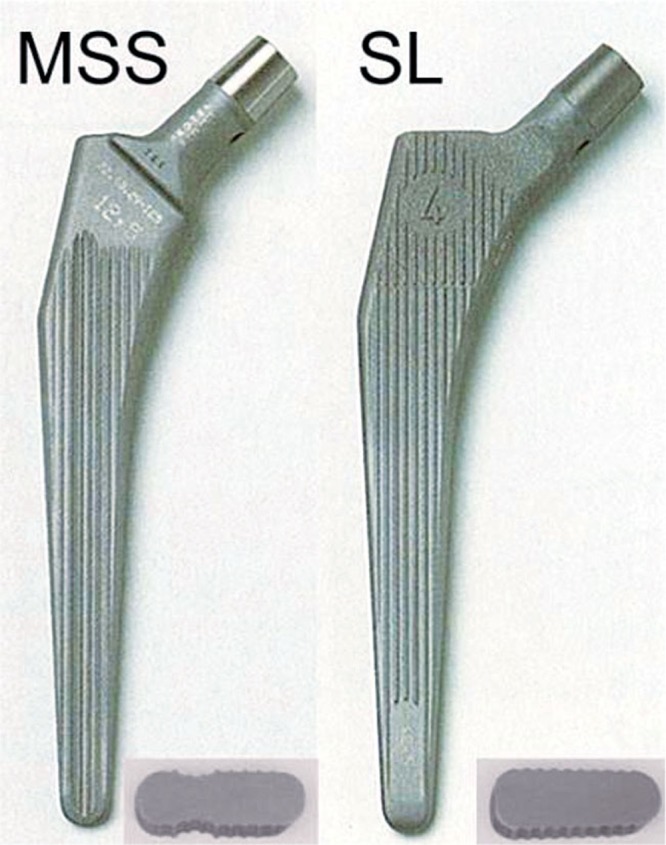

In this series of 828 hip replacements, we have now analyzed 4 different versions of cemented Müller-type straight stems implanted in 4 consecutive time intervals (Table 1). These 4 versions represent 2 different designs (the original MSS design and the SL design; Figure 1) which differ in shape and surface finish (Table 2, see Supplementary data). The MSS design is double-tapered with longitudinal grooves running anteriorly and posteriorly and a small collar proximally. The SL design is somewhat triple-tapered, lacking the anterior and posterior grooves and the proximal collar. Both designs were available in 2 materials, Co and Ti. All stems were forged, and the surface was finished by grit-blasting.

Figure 1.

The 2 different designs of cemented Müller-type straight stems: MSS with standard offset and SL. Only the Co versions are shown. The inserts show cross sections of the proximal third.

Both designs were implanted in 6 different sizes. MSS and SL differed in offset: for the MSS, standard and lateral offsets were available (6 mm difference); for the SL stem, there was only one offset, which was 3 mm more than that of the standard MSS.

All patients were operated in supine position through a lateral transgluteal approach. Implants were cemented line-to-line with the final broach (El Masri et al. 2010), but in contrast to other canal-filling implants like the Kerboul stem, the medullary canal was prepared with broaches that did not remove cancellous bone in the sagittal plane (Kerboul 1987, Clauss et al. 2010). All stems were cemented using a second-generation cementing technique (distal plug, cement syringe, no vacuum-mixing, no jet lavage, and no proximal sealing) with Sulfix-6 bone cement without antibiotics (low viscosity, Zimmer). Stems were combined with different cups and bearings (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cup and bearing combinations. All implants were Zimmer (Winterthur, Switzerland). Values are number of cups (%)

| MSS Co | MSS Ti | SL Ti | SL Co | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cup | |||||

| Cemented a | 149 (87) | 53 (20) | 0 | 0 | |

| Cemented + ARR | 16 (9) | 59 (22) | 22 (9) | 23 (15) | |

| Cemented + BSR | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Cementless b | 6 (4) | 154 (58) | 209 (90) | 131 (84) | |

| Bearing | |||||

| PE/ceramic | 40 (23) | 237 (89) | 197 (85) | 119 (76) | |

| PE/metal | 132 (77) | 30 (11) | 3 (1.3) | 0 | |

| Metal/metal c | 0 | 0 | 33 (14) | 37 (24) |

ARR: Müller reinforcement ring;

BSR: Burch-Schneider reinforcement ring;

PE: polyethylene.

a Müller low-profile PE cup.

b Müller SL-I cup. Cementless titanium shell with a fine-blasted surface, 5 screw-holes, 3 slots, and an additional lateral flange (Krieg et al. 2009).

c Metasul.

During the whole study period, cemented low-profile PE cups were used (either alone or in combination with an acetabular reinforcement ring (ARR) or anti-protrusion cage (BSR)). In the period of the MSS Ti from March 1989 onwards, a hemispherical modular titanium press-fit cup (SL-I) was implanted as clinical routine. For more difficult acetabular configurations, reinforcement rings were used. 563 heads (68%) were 28 mm in diameter and 265 (32%) were 32 mm in diameter. 66 (20%) of the cemented cups and 497 (99.4%) of the cementless cups were combined with a 28 mm head.

Statistics

We performed survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier curves with various endpoints: (1) revision of the stem and/or cup (including exchange of the liner) for any reason, (2) aseptic loosening of the stem, (3) stem loosening for any reason, (4) a worst-case scenario with all cases lost to follow-up, judged as aseptic loosening of the stem, and (5) aseptic loosening of the cup. Differences between survival rates after 15 years were compared by log-rank analyses.

We performed univariable Cox regression analysis to identify factors associated with an increased incidence of aseptic loosening of the stem. These included age (< 50, 50–59, 60–75, > 75 years), sex, primary diagnosis (primary osteoarthritis, fracture, inflammatory arthritis, other), type of implant (MSS, SL), implant material (Co, Ti), stem offset (MSS standard, SL intermediate, MSS lateralized), stem size (7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20), type of cup (cemented, cementless), and head diameter (28 mm, 32 mm). We calculated hazard ratios for revision for aseptic loosening with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Factors associated with an increased incidence of aseptic loosening (with the level of significance at p ≤ 0.1) were considered for inclusion in a multivariable Cox regression analysis with stepwise variable selection. Those statistically significant factors (p ≤ 0.05) that remained in the model were considered to be independent risk factors for aseptic loosening of the stem. To investigate the assumption of proportionality, hazard function plots and log-minus-log plots of all covariates were inspected visually. For each of the analyses, there was no sign of insufficient proportionality, and log-minus-log plots ran parallel for all covariates. The hazard ratio was used as a measure of relative risk (RR) (Rud-Sorensen et al. 2010). Adjustment for bilaterality was not performed (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003) as we found no differences in the Cox regression including only the first implantation or both.

We used the SPSS package (Statistics 20; IBM Corp., Somers, NY).

Results

Demographic data

The ages were similar in the 4 study groups. Of the patients who received the MSS, the proportion of males was 54%, which was less than the proportion of males among the patients who received the SL (64%). Primary osteoarthritis was the most common diagnosis (Table 1). The 4 groups showed marked differences in the combination of cups and bearing surfaces (Table 3).

Follow-up

For the 828 hips, there were 492 cases of death during follow-up (59%) from causes unrelated to the hip arthroplasty, and 24 (3%) hips were lost to follow-up after a mean time of 13 (2–22) years, without revision of either the stem or the cup. 106 patients (13%) had both hips replaced during the study period.

156 stems were revised: 139 (89%) for aseptic loosening, 7 (4%) for septic loosening, and 10 (6%) for other reasons (Table 4).

Table 4.

Stem revision during follow-up. Values are number of stems (%)

| Reason for revision | MSS Co (n = 172) |

MSS Ti (n = 267) |

SL Ti (n = 233) |

SL Co (n = 156) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aseptic loosening | 10 (6) | 45 (17) | 69 (30) | 15 (10) |

| Septic loosening | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Other revisions | 3 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (3) | 0 |

| Total revisions | 15 (9) | 49 (18) | 76 (33) | 16 (10) |

| Stem revision without inlay | 2 (1) | 7 (3) | 10 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Stem revision with inlay | 1 (0.6) | 32 (12) | 55 (24) | 9 (6) |

| Stem and cup revision with inlay | 12 (7) | 10 (4) | 11 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Isolated cup revision with inlay | 15 (9) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2) | 4 (3) |

The mean time until revision for aseptic loosening of the 139 stems was 8 (SD 4.5) years with statistically significant differences between the 4 stems (MSS Co, 13 (SD 4.3) years; MSS Ti, 7 (SD 5.1) years; SL Co, 11 (SD 2.7) years; and SL Ti, 6 (SD 3.4) years; p < 0.001). 23 (17%) of these revisions were combined with an exchange of the cup (11 cemented, 12 cementless) after a mean of 9 (SD 5.4) years, 96 (69%) with an exchange of the liner after a mean of 7 (SD 3.7) years and 20 (14%) without exchange of the cup and/or liner after a mean of 10 (SD 5.5) years.

25 hips (3%) had an isolated cup revision for aseptic loosening after a mean time of 10 (SD 6.4) years: 15 were cemented cups with a mean time to revision of 13 (3–22) years and 10 were cementless ones with a mean time to revision of 5 (1–13) years (Table 4).

Survival analysis

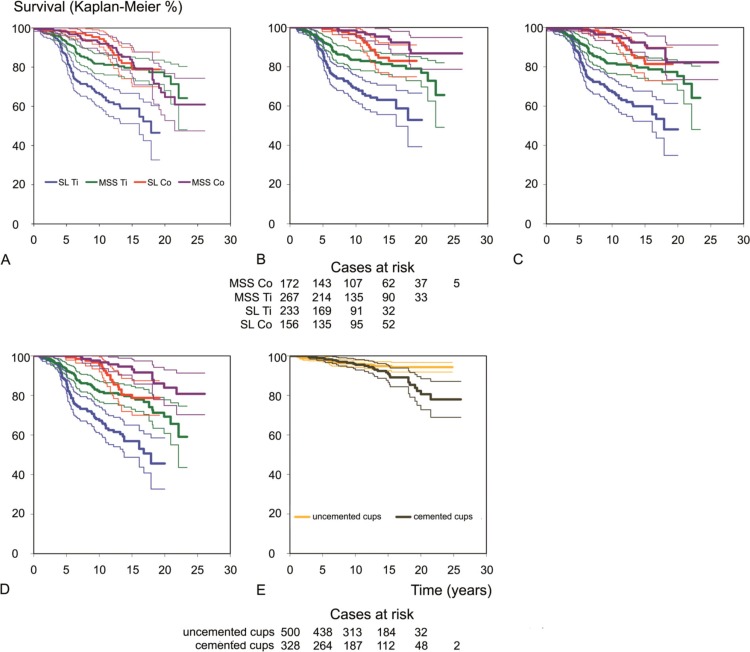

15-year survival with revision of any component (stem and/or cup (including exchange of the liner)) for any reason as endpoint was 82% (CI: 75–90) for MSS Co, 79% (CI: 70–88) for SL Co, 80% (CI: 74–85) for MSS Ti, and 59% (CI: 51–67) for SL Ti (p < 0.001, log-rank test) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier charts for stem survival (bold lines) with 95% confidence intervals (thin lines). A. Revision for any reason of any component (stem and/or cup (including exchange of the liner)). B. Aseptic loosening of the stem and cases at risk at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years. C. Stem revision for any reason. D. Worst-case scenario for aseptic loosening, counting all stems lost to follow-up as aseptic loosening. E. Aseptic loosening of the cup and cases at risk at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years.

Stem survival. As we wanted to investigate the effect of design modifications of the stem on long-term survival, we performed a survival analysis focusing on the stem alone. With revision for aseptic loosening of the stem as the endpoint, survival at 15 years was 94% (CI: 89–99) for MSS Co, 83% (CI: 75–91) for SL Co, 81% (CI: 76–87) for MSS Ti, and 63% (CI: 56–71) for SL Ti (p < 0.001, log-rank test) (Figure 2B). Survival rates with stem revision for any reason as the endpoint were 91% (CI: 85–97) for MSS Co, 81% (CI: 73–90) for SL Co, 80% (CI: 74–85) for MSS Ti and 60% (CI: 52–68) for SL Ti (p < 0.001, log-rank test) (Figure 2C).

Counting all 24 stems that were lost to follow-up as revised for aseptic loosening (the worst-case scenario), survival was 93% (CI: 88–98) for MSS Co, 79% (CI: 70–87) for SL Co, 79% (CI: 73–85) for MSS Ti, and 57% (CI: 49–65) for SL Ti at 15 years (p < 0.001, log-rank test) (Figure 2D).

Cup survival. Cup survival with aseptic loosening as endpoint was 91% (CI: 87–95) for the cemented cups and 95% (CI: 93–97) for the cementless SL cup at 15 years (p = 0.04, log-rank test) (Figure 2E).

Risk factors for aseptic loosening of the stem

22% (106 of 485) of the stems implanted in male patients were revised, as compared to 9% (32 of 343) in female patients (p < 0.001) (Table 5, see Supplementary data). Patients aged less than 50 years were more likely to have a revision for aseptic loosening of the stem than patients older than 75 years (crude RR = 3.9; p = 0.004).

Compared to larger implants (size ≥ 15), the smaller stems (size 7.5) were more likely to be revised for aseptic loosening (p = 0.001). The crude RR for revision for aseptic loosening was higher (3.5) for the SL stems than for the MSS standard stems (p < 0.001), and stems made of Ti had a 3.6-fold higher RR than the Co stems (p < 0.001) (Table 5, see Supplementary data). For the lateral stems (MSS), we found a 2-fold higher crude RR for revision due to aseptic loosening than for the standard stems (p = 0.02). The SL stem has only one intermediate offset. Offset (3 offset versions: MSS standard, SL intermediate, MSS lateral) was not an independent risk factor in the multivariable analysis.

Adjusting the risk ratio for all 4 stem versions for age, sex, cup, stem design, material, and size, these variables were independent risk factors for aseptic loosening of the stem (Table 5, see Supplementary data). Overall, the risk ratio for aseptic loosening of the stem increased to 8 (CI: 4–15) when comparing the most and the least successful versions (MSS Co vs. SL Ti).

Discussion

Modifications in the design of established stems may have a deleterious impact on long-term performance (Learmonth et al. 2007, Espehaug et al. 2009, Ellison et al. 2012, Hallan et al. 2012). The 20-year survival of the original MSS (Co) exceeds 86% with aseptic loosening as the endpoint, and is comparable to that of other successful cemented implants (Clauss et al. 2009). However, later developments in the stem design have been proven to reduce short- and mid-term survival instead of bringing about further improvements as expected (Maurer et al. 2001, Schweizer et al. 2005).

One weakness of our study was that the 4 stems investigated were combined with different cups. Aseptic loosening of the cup and stem are interconnected (Clement et al. 2012), with inferior cups protecting the stem and vice versa. In our series, the uncemented cups had better survival regarding aseptic loosening than the cemented ones. But most of the cups were combined with an inferior stem, which may have had a positive effect on cup survival. Furthermore, 96 cups had liner exchange during stem revision after a mean of 7 years, thus improving prognosis for fixation. Taking this into account, differences in survival were small between the cups used, and the effect observed for the stems cannot be explained by cup performance.

Furthermore, the cups may differ in their patterns of wear—and wear might affect the outcome of the stem. PE wear causes osteolysis and loosening of the cup, and to a lesser extent of the stem, which was shown for the MSS Co (Clauss et al. 2009). PE wear may be more important for uncemented modular cups, due to thin PE layers and additional back-side wear (Clement et al. 2012). For the uncemented cups presented, 34 of the retrieved liners were examined for wear. The mean annual wear rate was 0.08 mm, and back-side wear was less than 3% as compared to the volumetric articular wear (Krieg et al. 2009). The annual wear rate of the cemented PE cups combined with the MSS Co was 0.07 mm, all with 32-mm heads (Clauss et al. 2009). The polyethylene used (production, sterilization, and machining) was the same for the cemented and the uncemented systems (as quoted by the manufacturer). Thus, the volume of polyethylene debris should have been rather similar for both systems (Ilchmann et al. 2012), and it is improbable that difference in annual volumetric wear caused the differences in stem survival.

Younger age, male sex, and diagnosis are established risk factors for aseptic loosening of the stem (Havelin et al. 2000, Herberts and Malchau 2000, Malchau et al. 2002). We also found male sex and young age to be independent risk factors for aseptic loosening for the 4 versions of cemented Müller-type straight stems described.

Lateral-offset MSS stems had an increased RR for aseptic loosening as compared to standard-offset MSS stems, which was also shown by Hallan et al. (2012). Furthermore, small-sized stems had an increased RR for aseptic loosening. This has already been described for Muller-type straight stems by Hallan et al. (2012), and it has also been shown for other cemented stem systems (Thien and Karrholm 2010). Rotational forces at the interface of cemented stems are a main contributor to cement deterioriation and loosening of cemented stems. In the case of rotation, lateral offset in combination with small stems creates a high degree of strain in relation to a reduced implant surface area, increasing the risk of loosening (Asayama et al. 2005). Concerning this risk, small stems with high offset should be avoided but the clinical benefits of more offset are better hip stability, range of motion, and abductor muscle strength (McGrory et al. 1995)—so offset has to be well balanced.

Aseptic loosening of cemented stems is influenced by the longevity of the cement-bone and the cement-prosthesis interface (Howell et al. 2004, Scheerlinck and Casteleyn 2006). It has been clearly shown that improvements in the preparation of the bone bed (jet lavage) and cementing technique (vacuum-mixing, pressurization) have reduced the risk of aseptic loosening of the stem (Herberts and Malchau 2000, Malchau et al. 2002). All implants studied were operated with a second-generation cementing technique; the use of a better cementing technique may also have improved the long-term survival. The quality of the cement-bone interface should have been the same in the 4 groups; thus, the differences in long-term survival of the 4 cohorts must be attributable to changes in the stem design and material.

Initial bonding of the cement to the implant surface may be superior with rough surfaces (Verdonschot and Huiskes 1998). Kadar et al. (2011) reported excellent primary stability for the Spectron EF stem (rough surface finish) in an RSA study. But even after 5 years, the results were inferior with this surface modification (Espehaug et al. 2009)—while the original Spectron femoral stem (with satin-finished surface) has been one of the best-performing stems in the Swedish National Arthroplasty Register (Malchau et al. 2002). Slight debonding at the cement-stem interface is common in cemented stems, resulting in micromotion at the interface with consecutive metal and cement wear, osteolysis, and destruction of the cement mantle (Verdonschot and Huiskes 1998, Bartlett et al. 2009, Akiyama et al. 2013). Wear modalities (abrasion vs. fretting) and the volume of worn-off particles at the cement-stem interface are directly correlated with surface roughness (Howell et al. 2004, Akiyama et al. 2013). All 4 variants of the stems examined were not polished, and roughness exceeded Ra =0.4 µm, which is considered to be the upper limit to avoid abrasive wear (Howell et al. 2004). Due to abrasive wear, they produce a higher volume of metal and cement wear particles at the cement-prosthesis interface than polished stems (Ra < 0.4 µm) which have fretting wear. In force-closed fixation (complete and thicker cement mantle), survival is superior for polished stems (Howie et al. 1998, Morscher et al. 2005). With shape-closed fixation (incomplete and thinner cement mantle, so-called French Paradox (Langlais et al. 2003)), Hamadouche et al. (2008) also found better survival for polished stems than for the rougher grit-blasted stems.

In our series, the proximal third of the stems with SL design was rougher than for the MSS design, and also showed inferior results, irrespective of material (Co or Ti). For both designs (MSS and SL), the risk of loosening was increased for the stems made of Ti. Premature failure of cemented titanium stems has been attributed to early debonding of the cement-stem interface due to low flexural strength compared to other materials (Janssen et al. 2005). The combination of a material with low flexural strength (Ti) and a rough surface in the proximal third of the stem (Ra = 3–5 µm in the SL design) gave the worst results.

In conclusion, cemented Müller-type straight stems should be MSS-shaped, made of a material with high flexural strength (e.g. Co), and the surface finish should be polished (Ra < 0.4 µm). These technical considerations in combination with modern cementing techniques should improve the survival of Müller-type straight stems. This may be true for all types of cemented stems.

Acknowledgments

MC and TI: study design, data analysis, and writing of manuscript. SG: data management and analysis. AB: data analysis.

We thank Ms Susanna Häfliger for her exceptional efforts in organizing the follow-up examinations of our patients in the last 25 years; also, Prof. Peter E. Ochsner and Martin Lüem BSc for implementing and maintaining the in-house register.

No competing interests declared.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 5 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 5747.

References

- Akiyama H, Yamamoto K, Kaneuji A, Matsumoto T, Nakamura T. In-vitro characteristics of cemented titanium femoral stems with a smooth surface finish . J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(1):593–603. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayama I, Chamnongkich S, Simpson KJ, Kinsey TL, Mahoney OM. Reconstructed hip joint position and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(4):414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett GE, Beard DJ, Murray DW, Gill HS. In vitro comparison of the effects of rough and polished stem surface finish on pressure generation in cemented hip arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2009;80(2):144–9. doi: 10.3109/17453670902876755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter AE, Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Pedersen DR, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Leinen JA, Johnston RC. Results of Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved femoral cementing techniques. a concise follow-up, at a minimum of twenty-five years, of a previous report . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(7):1481–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M, Luem M, Ochsner PE, Ilchmann T. Fixation and loosening of the cemented Muller straight stem: a long-term clinical and radiological review . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(9):1158–63. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B9.22023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss M, Ilchmann T, Zimmermann P, Ochsner PE. The histology around the cemented Muller straight stem: A post-mortem analysis of eight well-fixed stems with a mean follow-up of 12.1 years . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(11):1515–21. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B11.25342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement ND, Biant LC, Breusch SJ. Total hip arthroplasty: to cement or not to cement the acetabular socket? A critical review of the literature . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(3):411–27. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison P, Hallan G, Hol PJ, Gjerdet NR, Havelin LI. Coordinating retrieval and register studies improves postmarket surveillance . Clin Orthop. 2012;11(470):2995–3002. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Masri F, Kerboull L, Kerboull M, Courpied JP, Hamadouche M. Is the so-called ‘French paradox’ a reality? Long-term survival and migration of the Charnley-Kerboull stem cemented line-to-line . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(3):342. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.23151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. 18 years of results with cemented primary hip prostheses in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: concerns about some newer implants . Acta Orthop. 2009;80(4):402–12. doi: 10.3109/17453670903161124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JL, Gie GA, Lee AJ, Ling RS. Experience with the Exeter total hip replacement since 1970 . Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19(3):477–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallan G, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Wangen H, Hol PJ, Ellison P, Havelin LI. Is there still a place for the cemented titanium femoral stem? 10,108 cases from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(1):1–6. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.645194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadouche M, Baque F, Lefevre N, Kerboull M. Minimum 10-year survival of Kerboull cemented stems according to surface finish . Clin Orthop. 2008;466(2):332–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie SA, Vollset SE. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(4):337–53. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts P, Malchau H. Long-term registration has improved the quality of hip replacement: a review of the Swedish THR Register comparing 160,000 cases . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(2):111–21. doi: 10.1080/000164700317413067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell JR. Jr., Blunt LA, Doyle C, Hooper RM, Lee AJ, Ling RS. In vivo surface wear mechanisms of femoral components of cemented total hip arthroplasties: the influence of wear mechanism on clinical outcome . J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie DW, Middleton RG, Costi K. Loosening of matt and polished cemented femoral stems . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998;80(4):573–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b4.8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilchmann T, Luem M, Pannhorst S, Clauss M. Acetabular polyethylene wear volume after hip replacement: Reliability of volume calculations from plain radiographs . Wear. 2012;282-283:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen D, Aquarius R, Stolk J, Verdonschot N. Finite-element analysis of failure of the Capital Hip designs . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87(11):1561–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B11.16358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadar T, Hallan G, Aamodt A, Indrekvam K, Badawy M, Havelin LI, Stokke T, Haugan K, Espehaug B, Furnes O. A randomized study on migration of the Spectron EF and the Charnley flanged 40 cemented femoral components using radiostereometric analysis at 2 years . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(5):538–44. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.618914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerboul M. Postel M, Kerboul M, Evrard J, Courpied J P. Total hip replacement. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1987. The Charnley-Kerboul prosthesis ; pp. 13–7. [Google Scholar]

- Krieg AH, Speth BM, Ochsner PE. Backside volumetric change in the polyethylene of uncemented acetabular components . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(8):1037–43. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.21850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais F, Kerboull M, Sedel L, Ling RS. The ‘French paradox.’ . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003;85(1):17–20. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.13948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement . Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, Garellick G, Soderman P. The Swedish Total Hip Replacement Register . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2002;84:2–20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200200002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer TB, Ochsner PE, Schwarzer G, Schumacher M. Increased loosening of cemented straight stem prostheses made from titanium alloys. An analysis and comparison with prostheses made of cobalt-chromium-nickel alloy . Int Orthop. 2001;25(2):77–80. doi: 10.1007/s002640000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrory BJ, Morrey BF, Cahalan TD, An KN, Cabanela ME. Effect of femoral offset on range of motion and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77(6):865–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morscher EW, Berli B, Clauss M, Grappiolo G. Outcomes of the MS-30 cemented femoral stem . Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2005;72(3):153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register . BMC Musc Dis. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rud-Sorensen C, Pedersen AB, Johnsen SP, Riis AH, Overgaard S. Survival of primary total hip arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis patients . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):60–5. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerlinck T, Casteleyn PP. The design features of cemented femoral hip implants . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88(11):1409–18. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B11.17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer A, Luem M, Riede U, Lindenlaub P, Ochsner PE. Five-year results of two cemented hip stem models each made of two different alloys . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125(2):80–6. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thien TM, Karrholm J. Design-related risk factors for revision of primary cemented stems . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(4):407–12. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.501739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonschot N, Huiskes R. Surface roughness of debonded straight-tapered stems in cemented THA reduces subsidence but not cement damage . Biomaterials. 1998;19(19):1773–9. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.