Abstract

The purpose of this concept analysis is to uncover the essential elements involved in caregivers’ resilience in the context of caring for children with chronic conditions. Walker and Avant’s methodology guided the analysis. The study includes a literature review of conceptual definitions of caregiver resilience in caring for children with chronic conditions. The defining attributes and correlates of caregiver resilience are reviewed. Concept analysis findings in a review of the nursing and health-related literature show that caregiver resilience in the context of caring for chronically ill children can be defined within four main dimensions, ie, disposition patterns, situational patterns, relational patterns, and cultural patterns. Empiric measurements of the impact of caregiver resilience applied to caregivers with children with chronic conditions are also reported in the analysis. The findings of this concept analysis could help nurses and health care providers to apply the concept of caregiver resilience in allied health care and be applied to further studies.

Keywords: caregiver resilience, children, chronic conditions, concept analysis

Introduction

A caregiver under severe stress, such as one caring for a child with a chronic condition, may experience cognitive, emotional, social, or instrumental imbalances that can disturb family functioning. Taiwan has more than 320,000 caregivers who are trying to cope with this situation. Thoroughly reviewing the related research allows us to build upon the foundation of existing knowledge and go on to develop a fresh outlook for the future of the care-giving sciences.1 Caregivers must be able to respond to such situations. Rutter suggested that resilience is a popular concept because of the desire for hope and optimism in the face of adversity.2 But what does caregiver resilience mean in the context of caring for chronically ill children? Concept analysis is a rigorous method used to provide a shared understanding of a concept. It is essential to define the boundaries of the concept of caregiver resilience so that newer practice methods can remain true to its essential elements. The aim of a concept analysis is to clarify the meaning of resilience in terms of caregivers who care for children with chronic conditions.

Materials and methods

Walker and Avant’s approach was used to guide this concept analysis and to clarify the attributes and characteristics of resilience of caregivers.3 There are various approaches to undertaking concept analysis. Walker and Avant’s method is the one most commonly used in the nursing field because it provides a clear and systematic process.3 The goal of the literature review in a concept analysis is to obtain literature that provide definitions of the attribute. It is a strategy that allows us to clarify the attributes of a concept. Concept analysis includes the following steps: selecting a concept; determining the aims or purposes of analysis; identifying all uses of the concept that can be discovered; determining the defining attributes; constructing a model case; constructing borderline, related, contrary, invented, and illegitimate cases; identifying antecedents and consequences; and defining empiric referents. The final procedural step is defining the empiric referents, and assessment or measurement of the concept is addressed in the findings.

The first author of this paper is an instructor who has been taught pediatric nursing and has worked with caregivers of chronically ill children for 18 years. All the following cases are real-life stories.

In analyzing the resilience of a caregiver, the following assumptions are made: adversity (eg, parenting a child who is chronically ill) or chronic stressors invite challenge, creating more possibilities, and people (caregivers) have intrinsic characteristics and capacities to heal themselves and are capable of adapting to adversity.

Selection of the concept and purpose of analysis

The first two steps in Walker and Avant’s process require identification of a suitable concept and determining the aims of the analysis.3 The concept of resilience was originally developed by studying the positive adaptation of children under adverse circumstances.2,4 However, what does resilience mean for individuals who are caring for chronically ill children? How can nurses intervene in this process? These questions led us to expand our science and to arrive at a new understanding of how caregiver resilience in caring for children with chronic conditions manifests in nursing practices and those of allied health professionals.

As research has evolved, the perspective of strength represents a paradigm shift in psychology from the deficit medical model to one that recognizes strength in clients who are under stress.5–7 The stress and coping theory was developed from a pathologic viewpoint to one of strength during the 1980s and 1990s. Modern resilience studies originated among psychologists and psychiatrists. Researchers emphasized that strengths and capacities are important resources for promoting good health. Early efforts to describe resilience focused on the personal qualities of resilient individuals, such as autonomy and self-esteem.8

In recent years, the relationship between nurses and clients has become more balanced. Professional authority is on the decline. Researchers attach much weight to ideals such as resilience, self-efficacy, self-management, and empowerment. Some researchers indicate that certain nursing terminology should be replaced by overcoming adversity and protective mechanisms.9 Protective factors can be interpreted as either preventing risk or as moderating the effects of risk.10 It is now most common to use the second sense, ie, factors that buffer against stress.11,12

A review of the literature in academic journals found the concept of resilience to be widely used, due to minimal concept analysis of resilience among caregivers of children with chronic conditions in the allied health literature. In order to characterize the resilience of caregivers, it is necessary to identify and analyze this concept. Health care practitioners can look to this definition to expand what is known about individual resilience or caregiver resilience.

Identify all uses of the concept that can be discovered

To conduct the concept analysis, we used the Medline, CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO databases to search the literature. References for each publication were also hand-searched for more data. Internet search engines, such as Google Scholar, were used to identify subsequent publications corresponding to the concept. The concept of resilience has been applied primarily in physics to mean elasticity (stretch out and draw back). Historical use of the term, resilience, was first studied by Murphy and Moriarty and understood to mean coping despite obstacles.13 McCubbin and Patterson introduced the concept of resilience, defining it as an adaptation process used by families to cope with a stressful situation.14 However, it did not become well known in the literature until Werner and Smith began publishing on the concept. In the 1980s, the concept took on an expanded definition to include physiologic and psychologic meanings.4 Rutter states that “biological studies on resilience to diseases or physical hazards show that resilience does not derive from avoidance of risks but from controlled exposure”.15

Determine the defining attributes in nursing and health-related literature

The findings are reported for the extracted attributes, antecedents, and consequences. In addition, a model case and a related case are provided based on the concept analysis. The method of Walker and Avant was used to discover and analyze the concept, events, or incidents that occur as a result of occurrence of the concept, and the classes or categories of actual phenomena that demonstrate the occurrence of the concept itself.3

The attributes of resilience were delineated from the literature review. In accordance with current dictionary definitions, use of the term in the literature is deemed appropriate.3 The conceptual content is closely related to the word meaning. According to the online Oxford English Dictionary, the original use of the word resilience is “the ability to rebound or spring back, the power of something to resume its original shape or position after compression or bending”17 Resilience as a verb is defined as to “rebound, kick-back, spring-back or leap” and as a noun is defined as “power, strength, ability, capacity”. The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines it as the capability of a strained body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by compressive stress or as the ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change. 17

In physics, “power” refers to the function that can make other objects move, remain still, or change their direction. Of the literal meanings of resilience, its meaning of “rebounding power” seems most relevant for this analysis. Other definitions of resilience include recovery from or elastic response to a stressful cause. Curly defines resilience as a patient’s capacity to return to a restorative level of functioning by using compensatory and coping mechanisms.18 When discussing social systems, Simonsen defines resilience as the ability of human communities to withstand and recover from stresses.19

Resilience has different aspects when translated into Chinese. The meaning in Chinese is strength to fight adversity, to recover, to restore, to be flexible, to be elastic, to be adjustable, and to be pliable, but strong, tenacious, tough, soft, lithe, or easily bent. Resilience in Mandarin Chinese is “Ren”, which refers to the nature of a thing which is pliable and not easily torn apart, such as the ability to spring back after being bent, stretched, or deformed. Caregivers must not only bounce back, but must also bounce forward, transcend difficulties, reintegrate into society, and move on with life in a positive way. To do this, the person must be pliable. The quality of reintegration has appeared consistently throughout the literature.4,20–24

The term resilience is used across disciplines, ages, groups, and cultures. The concept of family resilience can be viewed in terms of individual family members or the family as a unit.25–28 Family resilience appears to reside in relationships among family members characterized by cohesiveness and shared values. Caregiver resilience and family resilience are different phenomena but are closely related. Personal characteristics were strongly related to caregivers response to major life stressors and to maintain external relationships. To find the role of self-understanding in resilient individuals is important. The key attributes of individual resilience as distinct from family resilience are maturity, empowerment, creativity, and sense of belonging, whereas the characteristic attributes of caregivers’ resilience are responsiveness to stress, self-understanding, the desire to maintain normal states, readiness to accept critical situations, the ability to take responsibility for causing trouble, being content with things as they are, patience in attaining goals, and remaining adaptable.14

In contrast with the conceptualization of caregiver resilience as a process concept, some authors have defined it as a property concept.29 Resilience is a property, or characteristic, that causes changes in a person’s ability to function according to their own value system when facing major life stressors. Patterson regarded resilience as one property of family functioning, ie, as an ability to maintain a balance between change and stability within the family.30 McCubbin and McCubbin viewed the outcomes of the process of transformation in which resilience becomes incorporated as a power and propelling energy.26 Several researchers have advanced the concept of resilience as a process rather than as a property. The focus of empiric work has also shifted away from identifying the protective or recovery factors underlying the concept and moved to understanding it as more of a protective process. Woodgate explained resilience as an active process that develops internal resources for coping with stress.28 Rutter indicated that resilience is an interactive concept referring to the capacity for successful adaptation in adversity, and the ability to bounce back after encountering difficulties, negative events, or tough times.31 Luthar defines resilience as a dynamic process that involves personal negotiation throughout life that fluctuates in different contexts.32 Resilience has been also defined as a process of confirming and developing resources and powers that control stress to achieve positive results and restore self-esteem, life satisfaction, and self-respect.24,34 The concept of caregiver resilience appears problematic and circular as a process concept.

The literature on caregivers of the chronically ill has linked the severity of clients’ conditions and the level of supervision needed with the level of caregiver burden.35 The neutral term appraise means to value. In this study, we analyzed the concept “resilience of caregivers who care for children with chronic conditions”. From an extensive literature review and analysis, the defining attributes of the concept include flexibility, resistance to stress, having a positive outlook, having problem-solving and coping skills, a sense of control adaptability, the ability to integrate socially, and resourcefulness. The most common definition of resilience used in the past few years is having the ability to adapt positively despite adversity.32

We analyzed and compared the data obtained from both theoretical and fieldwork settings in order to arrive at a final definition of the concept of caregiver resilience. We found that caregiver adjustments in response to stress impact on all aspects of family functioning, but were most closely associated with problem-solving functions within the cognitive construct (ie, intelligence, optimism, creativity, humor, and a belief in one’s self) and competencies (coping strategies, social skills, above average memory, and educational abilities). Caregivers appear to make endeavors to bring about positive behaviors, such as personal changes in relation to their value system, and have a sense of reality. In addition, resilience is considered a multidimensional and dynamic construct. The defining attributes of a concept are the characteristics of a concept that appear repeatedly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identified attributes of “resilience of caregivers of children with chronic conditions” in the fieldwork

| Dimensions | Item | Performance of no resilience | Performance of toughness (key factors often found in healthy caregivers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disposition pattern | Response | Negative emotional response (eg, crying, upset, depressed) Despair |

Confront with stresses Readiness to accept critical situations Emotional expressiveness |

| Focus | To magnify the problems Escape-avoidance (withdrawal)/fight |

Go with the flow Willingness and capacity to plan Tend to normalize |

|

| Intrinsic characteristics | Impulsive Blame fate and other people Strain oneself Take a pessimistic view (passivity) Being concerned about face-saving |

Tolerance for negative affect, being self-understanding, positive, proactive, humor, responsibility, autonomy, patience, empathy with others, adaptable, innovative, reflective, and flexible | |

| Situational pattern | Stress-coping mechanism | External locus of control Negative appraisals |

Internal locus of control Positive appraisals |

| Role transition | Beyond control | In control | |

| Relational pattern | External orientation | Tending to arouse suspicion (no trust, no confidence) Act in disregard of other people’s opinions, fight in isolation Confide secretively |

Seek help from others, sociable; pursue information, economic resources, cooperative with health care professionals, and family member leadership; participating in fun learning activities (hobbies) |

| Philosophical pattern | Interpretation/meaning | Focus on disability of a child Repay a debt from a previous life Compare with healthy children |

Focus on strengths of the child A balanced view of life Joy about slow progress of the child |

| Anticipated outcomes | Maladjustment Time strain Physical strain, physical fatigue, endure hardship Suffer an unpleasant situation |

Positive adaptation and transition Physical fitness, build up one’s strength, self-respect return to a normal condition, thriving in spite of a stressful situation, getting tough |

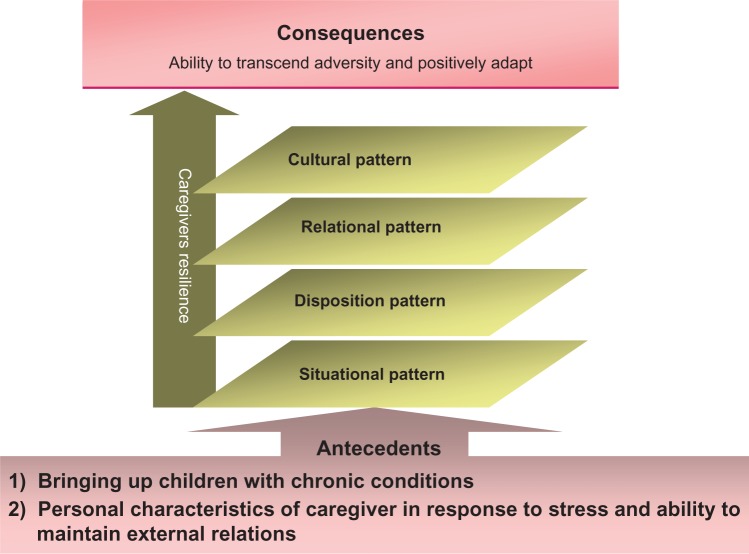

Caregivers have emphasized that internal strength of beliefs is a source of resilience. Polk has synthesized four patterns (dispositional, situational, relational, and philosophical) of resilience from the individual resilience literature.36 Philosophical means wise, reasonable, and calm. The major elements of culture are material culture, language, aesthetics, education, religion, attitudes and values, and social organization. However, we found resilience within the context of the caregiving experience, cultural backgrounds can influence individual’s worldview or life style. Therefore, we used “culture pattern” instead of Polk’s “philosophical pattern”. In our analyzing of the dimensional constructs of resilience, four constructs have emerged (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The dimensional constructs of resilience of caregivers of children with chronic conditions.

Disposition pattern

We found that caregivers with resilience in response to major life stressors had strong individual strength and a positive view of children with chronic conditions and their families. They had the ability to find and develop personal social skills, to solve problems, were creative and persistent, and had a good sense of humor as well as communication skills. They were also able to maintain a sense of normalcy in the presence of stress and continue to care for the child with chronic illness. Caregivers possessing these attributes are able to thrive in spite of stressful situations.

A review of the literature regarding caregiver resilience is presented. In our study, a philosophical pattern was also found. The personal characteristics of resilience include being able to accept and embrace change, and being willing to move on, work hard, and bounce back. They have self-understanding, self-confidence, tolerance of negative effects, positive cognition, are competent, and have a sense of coherence. They are thriving, tough, resourceful, proactive, responsible, patient, innovative, and flexible.21–23,37 Self-confidence is having the belief that one has the capability to manage the situation at hand and overcome life’s adversities. Caregivers need a greater ability to relax the body and release physical tension. Humor was a tool used by resilient caregivers. Resilient caregivers focused on solutions to problems and tended to normalize. They usually had a sense of mastery and an awareness of global self-worth. Inherent characteristics of caregivers may need to be considered as modifying factors.38

Situational pattern

Caregivers act in the face of stressful circumstances. They are competent at problem-solving and have clear goals and an organized strategy for achieving them. Resilience is an enabling force for personal functioning, especially in the context of caring for chronically ill children. A combination of active problem-solving and emotional expressivity may be particularly helpful.39 An internal locus of control has been shown to be necessary in fostering resilience. Hence, caregiver responses to stress impact on all aspects of family functioning, but are most closely associated with the problem-solving function within the cognitive construct.

Relational pattern

The relational pattern refers to the strength of interaction between individuals and resources in their environment. Factors affecting this pattern include the variety of resources available, quality of interactive experiences, social networks, methods of adjusting to negative interactive experiences, and the ability of a family to pull together. We also emphasize the importance of recognizing the dynamic interactive nature of resilience and the interplay between an individual and their broader environment. Environmental factors also include perceived social support. Resilient caregivers seek help from others. Having support and open communication with another individual is essential in fostering resilience.

Cultural pattern

Caregivers have a balanced view of life. Sociocultural strengths include internal belief (meaning faith or religion), external ability, and transitional experience. In Chinese culture, people usually go with the flow. They stay positive and give less attention to unwelcome thoughts. Finding ones’ own inner strength composed of positive attitudes, value, faith, spirit, and meaning can foster internal power related to resilience. For example, by imagining an ill child is an angel and a special gift from heaven to put the caregiver to a test, a resilient caregiver can emerge more loving, stronger, and more resourceful in meeting future challenges. Accepting and embracing change in a positive way is an important characteristic. Spirituality has been found to be an essential element of resilience, because it provides families with the ability to unite, understand, and overcome stressful situations.40

From this review, a definition of caregiver resilience has been derived by integrative analysis of the findings of a comprehensive review of the literature on resilience and empiric data. In analyzing the concept of resilience among caregivers of children with chronic conditions, a new definition has emerged. This paper defines “resilience of a caregiver” as follows: resilience is a process of interaction between a caregiver and the environment and is a balance between protective factors and risk factors. When placed in an unbalanced stressful situation, a caregiver proactively seeks balance in life, appraising the positive meaning of the event. Then, through self confidence and using inner and outer resources (or abilities) the caregiver transforms difficulties into positive situations. Such power can be called resilience. This definition of resilience in caregivers of children with chronic conditions that has emerged from the analysis can provide clarity and direction for future research in relation to children with chronic conditions.

Case studies

Several case studies are presented to highlight the components of this concept analysis. These cases also help us to identify attributes, antecedents, and consequences of caregiver resilience. The following cases are not invented, but are authentic records from practical interactions between caregivers and the authors.

The following case was used to compare and contrast the data from other caregivers to arrive at the definition and for delineation of the key attributes of this concept. The authors identified attributes of “resilience of caregivers of children with chronic conditions” in the fieldwork (Table 1).

Model case

This model case is a real-life example of the concept in which all the defining attributes are present. Walker and Avant stated, “It is a pure case of the concept, a paradigmatic example that demonstrates all the defining attributes of the concept.”3 Furthermore, the person with resiliency was more self-realized and treasured life more after having a child with a chronic condition. The following is an example of a model case for the concept.

Example

A 5-year-old boy was first diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus. The doctor told the parents their son would need insulin injections for the rest of his life. The family initially fell into despair, but soon they decided to ask for information to manage the situation (ability to control stress). The mother thought she needed to be a “strong mother”. This idea reinforces the notion of empowerment. She quit her job to care for the boy. She believed that her son was an angel sent to test her and the utmost efforts of her family would make her son well (sense of control and positive outlook). The sick child’s caregiver came to rely increasingly on her religion after the diagnosis (faith, transcendence, and spirituality). When she needed to make a decision, she always had a straightforward discussion about it with her husband (open communication and emotional expression). They had confidence in each other. The caregiver arranged for her daughter to move in with her grandmother, as she did not have time to care for her. She adapted to these new circumstances well (flexibility). She thought that they all should be strongly united (cohesion, mature thinking). When the boy’s condition was stable enough for him to go out, the caregiver usually made a family journey in order to spend time together (connectedness and maintaining a balance on the demands of family members). Her neighbor was a pediatric nurse, so the caregiver asked her for many tips about caring for a diabetic child (social and economic resources). She tolerated discomfort to overcome adversity. She had pride in herself for coping well with this difficult situation. She enjoyed helping other caregivers and sharing her experience (self-esteem).

In this case, the caregiver became flexible when trying to seek appropriate support and at the same time trying to normalize their situation. We examined the data repeatedly for themes and patterns until reaching a consensus on key attributes of caregiver resilience in model cases.

Borderline, related, and contrary cases

Constructing borderline, related, contrary, invented, and illegitimate cases allows one to clarify what the concept is like or similar to.

Borderline case: invulnerability

The borderline case is an example of the use of the concept in which some of, but not all, the defining attributes are present. In some early studies, the resilient child was described as invulnerable.4 In military terminology, someone who is vulnerable is easy to hurt physically or mentally, and lacking protection or defense. Invulnerability became a defense capability despite suffering adversity.26 The following is an example of a borderline case for the concept of resilience in caregivers of children with chronic conditions.

Example

Three years ago Mrs B’s child was diagnosed as having type 1 diabetes mellitus. Her character used to be optimistic and open, but she became sad and was not confident that she could take care of such a special kind of child. However, she discussed it with her family, and she led her life in a positive way. Even though neighbors gossiped about her, she told herself that she did not need to listen to it. Sometimes the process of seeking a doctor was not easy, but other family members and good friends would give her advice and comfort. When she felt she could not cope anymore and almost collapsed, good friends always appeared in time to comfort her. Although she was not content with the current situation, complaining that her fate was bad, she was still glad that she was in good enough health that she could take care of the child, and that so many people cared about her.

In this borderline case, health management is limited by the patient’s lack of interest in education and responsibility.

Related case: hardiness

A related case is a situation that is similar to the concept but does not share the critical attributes. Hardiness was chosen to illustrate a related concept of resilience. Hardiness means firm and persistent, with unswerving determination and inflexible will, and is unyielding. Resilience means the ability to accept stressors but not internalize them. Researchers analyzing concept and defining attributes of hardiness included a determined attitude of confronting influences resulting from stressful conditions, enduring the hardship process, rising up in resistance, actively participating in the caregiving process, and believing in the power of one’s own behavior to influence a situation. Hardiness refers to the case’s concept, which is similar to resilience, but does not consist of the judgmental characteristics of resilience. Rather than doing one’s best or being persistent, hardiness is described as determination and strong will. The evidence suggests that, compared with resilience, hardiness allows individuals to overcome adversity deliberately, but it does not require the results of change to be positive.17,26,53

Example

Three years ago, Mrs C’s child was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. At that time, she told herself that she must not cry, and that she must defend herself and must not be treated as a joke by her colleagues. Therefore, she quit her job and instead began working as a vendor selling ornaments. She often refused her husband’s parents’ care and advice, and would not allow them to intervene in the child’s care. She frequently argued with her husband about the child’s care. She even ignored neighbors’ concerns. In addition, she ignored registered nurses’ suggestions to attend support groups for parents. During a nurse’s visit, she stated, “I don’t really need you. I am fine.” She felt she should keep silent about her child’s illness. Mrs C arranged for her child to attend an early intervention class at a kindergarten affiliated with a government elementary school. Although the child made some progress, she and her child became isolated. Mrs C never had the drive to change nor the positive outlook that life was worth changing.

Contrary case

A contrary case is a clear example of an instance that is not the concept.3 This gives us information about what the concept should have as defining attributes if ones from the contrary case are clearly excluded. This is an example of a contrary case of resiliency, because it clearly does not depict the concept of resilience.

Example

Three years ago, Mrs D’s child was diagnosed with cerebral palsy. At that time she went into hysterics, crying in the hospital. Over the years she complained about heaven’s injustice. She often argued with her family over trivial things. She did not listen to the advice of professionals, often saying that they did not understand the child’s condition. She could not accept her child’s condition, feeling that the child’s birth seemed like a nightmare. She often burst into tears, wishing that the situation had never been. She took her child to temples, expecting a miracle. She interpreted neighbors’ concerns as ill-intentioned and mockery. The child did not make any progress and did not participate in any early intervention programs. The child was often hospitalized for illness, including pneumonia and fever. Mrs D had chronic stressors in her life and was not able to reintegrate socially or bounce back from the challenge. She did not believe she could change, did not have a positive outlook on life, and did not have a support group. Mrs D was inflexible and did not want to overcome her adversity.

Identify antecedents and consequences

Antecedent factors for caregiver resilience and outcomes of resilience were obtained from a wide-ranging review of the relevant literature. The vital attributes, antecedents, and consequences of caregiver resilience identified can be used to generate research questions regarding caregiver resilience in health care practice.

Antecedents

According to Walker and Avant, indicated antecedents are those events or incidents that must occur prior to the occurrence of the phenomenon.2 Resilience normally develops under difficult conditions.8 Hence, resilience requires the presence of clear substantial risk or adversity. Adversity must take place before resilience can be demonstrated or fostered.

Based on a review of the literature, some authors define resilience as an adaptive strength, postulating it to be an adaptive capacity for balance when confronting crises, and as a potential power of the caregiver who activates flexibility, problem-solving, and resource mobilization. It also needs to be superior to adversities of caregivers during their practical experiences.41 Antecedent factors include long-term stressors and strains that have accumulated over a long period, such as bringing up children with chronic conditions. Antecedent factors can also refer to the personal characteristics of caregivers who respond to stress and maintain their external relationships. Resilience concepts project similar notions in terms of the caregiver’s adaptation and the dynamic processes when confronted with adversity.

Consequences

The phenomenon of resilience requires a possible psychologic outcome and not just an unusually positive one or a supernormal functioning capacity. Resiliency can assist caregivers to adjust and recover life control quickly. Providing individual care for other less resilient people and being a valued member of the community that allows people to build supportive networks and thrive in spite of stressful situations can also be rewarding for caregivers. We believe that individuals who display this kind of resilience often function better as caregivers for children who are chronically ill. A consequence often is a decision (thought) or behavior (action). Under stressful conditions, caregivers build up protective lines for a more positive experience.

Uses of the concept: empiric referents

The final phase in the concept analysis method is to define empiric referents of the concept. Theoretical perspectives are needed to refine conceptualization and develop measurement tools to address outcomes in the specific context. Evidence-based research and measurement instruments for the concept have been critically reviewed. The literature published in the CINAHL, EBSCO, Medline, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases was searched from 1970 to 2010. Keywords used in the search included the following terms both separately and in various combinations: “concept analysis”, “resilience”, “chronic conditions”, “chronic illness”, and “child caregiver resilience”. Papers in English and Chinese were included. This theoretical work led to formulation of the definition of caregiver resilience.

Measurement of resilience

According to Walker and Avant, concept analysis and development is the fundamental process required by nurse researchers who are attempting to measure the metaphysical phenomena of health care practices.1 When measuring resilience from a holistic perspective, the positive aspects are especially emphasized. The Adolescent Resilience Scale (Oshio et al),42 Baruth Protective Factors Inventory,43 Brief Resilient Coping Scale (Sinclair and Wallston),44 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale45 (CD-RISC), Wagnild and Young Resilience Scale,46 Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA; Friborg et al),47 and Resiliency Scale (Jew et al)48 are proposed to measure resilience. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale45 and RSA47 were selected for review. Both these measures consist of the key components associated with resilience and are applicable to adults. The results indicated a relationship between resilience and personality.

The CD-RISC measures factors of resilience that include personal competence, high standards, tenacity, trust in one’s instincts, tolerance of negative affect, strengthening effects of stress, positive acceptance of change, secure relationships, control, and spiritual influences.45 The CD-RISC is a method of measuring resilience in various age groups and has been found to have sound psychometric properties.20 The CD-RISC was administered to 828 participants. A ten-item short-form unidimensional version of the CD-RISC has been developed and consists of resilience as a unitary dimension.49 Results from 1,743 undergraduate students indicated good internal consistency (α = 0.85) and construct validity of the measure.

The second instrument is the RSA, which consists of five factors of resilience, including personal competence, social competence, family coherence, social support, and personal structure.47 The most comprehensive and best indicator of resilience found on the adult and adolescent population was the resilience scale. The present version consists of 33 items using a seven-point semantic differential scale. Items consist of a stem with two responses at either end of the scale. The semantic differential scale has been shown to provide better estimates of reliability and validity for the RSA when compared with a Likert scale.50 Factor analysis demonstrated significant factor loadings for each item to the respective subscale. Finally, all subscales of the RSA were highly correlated with measures of personality, suggesting that if a person measures high in personal strength or social competence, then they are likely to have a coherent and stable family or social support network.

Polk, a nursing scholar, has mentioned a nursing model of resilience and a method of measuring it.51 The instrument is the Polk Resilience Patterns Scale. Resilience is a four-dimensional construct consistent with the simultaneity paradigm of nursing science. The indicators are personal structure/competence, which includes rebounding/reintegration, high expectancy/self-determination, and self-esteem/self-efficacy. One of the indicators is family coherence, which is referred to as positive relationships/social support, and social support/social competence. The other one is an easy temperament, and a sense of humor is an example of this. This paradigm views the human being as more than and different from the sum of the parts, changing mutually and simultaneously with the environment. The nature of this paradigm is one of a rhythmic process of increasing complexity. In this context, human beings perceive life as an all-at-once, multidimensional experience, with the meaning in any situation being related to the particular dynamics of that situation.51

Discussion

Health care practice implications

Over the past two decades, the concept of resilience has been gaining the attention of nursing scholars. Caregiver resilience, which is the concept of one’s adaptability in the case of caring for a child with a chronic illness, occurs through the interaction between protective and risk factors influenced by the individual and the environment. Protective factors are those attributes that help the individual buffer the effects of the stressor.33,52 This concept analysis provides guidance for clinicians working with caregivers of chronically ill children. In the allied health literature, the concept of resilience is measured indirectly, most often by measuring the family.20 Family strength research and the various models of family resilience have been developed by McCubbin et al.15,26 These include the Double ABCX model and most recently the Resiliency Model of Family Adjustment and Adaptation. A key coping strategy within resilience approaches involves reframing, ie, altering perceptions in a positive direction by seeing adversity as a challenge and opportunity.41 McCubbin and McCubbin identified both protective and recovery factors that work synergistically and interchangeably to respond successfully to crises and challenges.53 However, each family member develops their own pattern of problem-solving and decision-making patterns involving health matters that are seen in the lifestyle of the family. Hence our concerns are with the personal elements of resilience. Our study of resilience focused on characteristics that assist individuals to thrive during adversity.

Resilience is an enduring ability or capacity that is exhibited as strength of the caregiver when responding to chronic stresses and problem-solving. We believed that caregiver resilience is a capacity; we need to find ways to measure levels of caregiver resilience, because nurses need to apply different nursing interventions when the levels of resilience differ. Analysis of the concept can assist nurses caring for patients with chronic conditions to use positive perspectives and then apply different intervention strategies. Based on the concept analysis, implications for prevention and intervention research as well as future resilience studies are discussed. Through use of a practice model to explore patterns of resilience, it is hoped that the discipline of nursing and allied health will recognize the value of assessing and strengthening understanding of a client’s overall pattern of health. It may explore the possibility of resilience-based care intervention schemes.

This concept analysis is to uncover the processes involved in conceptualizing caregiver resilience in those caring for children with chronic conditions. Our findings could lead to the development of an instrument for measuring caregiver resilience. Using the attributes within the four dimensions, questionnaire items could be developed. This new way of defining resilience among caregivers of chronically ill children has the potential for developments in nursing and allied health science. Researchers can look to this definition to expand what is known about caregivers of chronically ill children, their experience of resilience, and its dimensions.

The dimensions of caregiver resilience suggested in this study should be validated further by a construct validity study.

Conclusion

We found caregivers tended to focus on the positive, and the caregivers’ belief was that child with a chronic condition is a special favor for them. Resilient caregivers are proactive towards gathering information and resources, maintaining cooperative relationships with health care professionals, and developing social networks. Assuming caregiver resilience is to be considered as a process specific to the context of caring a chronic condition child. It is daily, individualized to the person, and unique to the task. It is also a complex process in which there are physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects. The power of resilience enables caregivers to achieving balance, confidence, and personal strength. This definition can provide clarity and direction for future research. Empiric referents are also outlined. Via analysis of the concept, we can understand how caregivers respond to intervention factors under pressure. The knowledge that we have about personal and environmental characteristics that contribute to resilience of caregivers is valuable. It is expected that concept analysis in nursing and health professions can lead to positive ideals of care. A greater understanding and respect for the experiences of caregivers and how they use their outer and inner resources to transcend adversity can be a valuable resource for others.

Author contributions

FYL designed the study with guidance from JRR and TYL. The literature review, data collection, and data analysis was undertaken by FYL. Manuscript preparation was led by JRR and TYL. All authors contributed to development and revision of the paper.

Disclosure

The authors received no financial support for research and/or authorship of this paper. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chiou CJ, Hsu SM, Wu CM. Literature review of primary caregivers’ burden, stress and coping in Taiwan research. The J Health Sci (Taiwan) 2002;4:273–290. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ; Pearson Prentice Hall; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner E, Smith RS. Vulnerable but Invincible: A Longitudinal Study of Resilient Youth and Children. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazarus RS. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Leary VE, Ickovics JR. Resilience and thriving in response to challenge: an opportunity for a paradigm shift in women’s health. Womens Health. 1995;1:121–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selgiman M, Csikeszenmihalyi M. Positive psychology. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masten AS. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56:227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinard E. Methodological issues in assessing resilience in maltreated children. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:669–680. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luthar SS, Zelazo LB. Resilience and vulnerability: adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and Vulnerability. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghate D, Hazel N. Parenting in Poor Environments. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tusaie K, Dyer J. Resilience: a historical review of the construct. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy L, Moriarty A. Vulnerability, Coping, and Growth from Infancy to Adolescence. New Haven, CT: University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. Systematic Assessment of Family Stress, Resources, and Coping: Tools for Research, Education, and Clinical Intervention. St Paul, MN: Department of Family Social Science; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter M. Resilience: some conceptual considerations. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:626–631. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90196-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merriam-Webster Dictionary. [homepage on the Internet] Available from http://www.merriam-webster.com/Accessed August 15, 2013

- 17.Resilience Oxford English Dictionary online Available from: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/163619?redirectedFrom=resilience#eidAccessed July 15, 2013

- 18.Curly MAQ. Patient-nurse synergy: optimizing patient outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonsen S.Resilience Dictionary Stockholm Resilience Center, Stockholm University; 2007Available from: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/163619?redirectedFrom=resilience#eidAccessed October 12, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, Byers J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29:103–125. doi: 10.1080/01460860600677643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anthony EK. Cluster profiles of youths living in urban poverty: factors affecting risk and resilience. Social Work Res. 2008;32:6–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayalon L, Perry C, Arean P, Horowitz M. Making sense of the past-perspectives on resilience among holocaust survivors. J Loss Trauma. 2007;12:281–293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi NE, Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS. The role of dispositional resilience in regaining life satisfaction after the loss of a spouse. Death Stud. 2007;31:863–883. doi: 10.1080/07481180701603246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner E. Risk, resilience, and recovery: perspectives from the Kauai longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:503–515. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCubbin HI, McCubbin MA. Typologies of resilient families: emerging roles of social class and ethnicity. Fam Relat. 1988;37:247–254. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh F. The concept of family resilience: crisis and challenge. Fam Process. 1996;35:261–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodgate RL. Conceptual understanding of resilience in the caregiver with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1999;16:35–43. doi: 10.1177/104345429901600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egeland B, Carlson E, Sroufe LA. Resilience as a process. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson JM. Promoting resilience in families experiencing stress. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:47–63. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutter M. Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:1–12. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luthar SS, Sawyer JA, Brown PJ. Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: past, present, and future research. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:105–115. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyer JG, McGuinness TM. Resilience: analysis of the concept. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1996;10:276–282. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(96)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawley DR, DeHaan L. Toward a definition of family resilience: integrating life-span and family perspectives. Fam Process. 1996;35:283–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou KR. Caregiver burden: a concept analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2000;15:398–407. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2000.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polk L. Promoting resilience in families experiencing stress. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;42:47–63. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Rouke N. Psychological resilience and the well-being of widowed women. Ageing Int. 2004;29:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson GE. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy SA, Johnson C, Lohan J. The effectiveness of coping resources and strategies used by bereaved parents 1 and 5 years after the violent deaths of their children. Omega (Westport) 2003;47:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeFrain J.Strong families Family Matters 1999Available from: http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/fm/fm53jdf.pdfAccessed July 13, 2013

- 41.Walsh F. Strengthening Family Resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oshio A, Kaneko H, Nagamine S, Nakaya M. Construct validity of the Adolescent Resilience Scale. Psychol Rep. 2003;93:1217–1222. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.93.3f.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baruth KE, Carroll JJ. A formal assessment of resilience: the Baruth Protective Factors Inventory. J Individ Psychol. 2002;58:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinclair VG, Wallston KA. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment. 2004;11:94–101. doi: 10.1177/1073191103258144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagnild G, Young H. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993;1:165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience. What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;14:29–42. doi: 10.1002/mpr.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jew CL, Green KE, Kroger J. Development and validation of a measure of resiliency. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 1999;32:748–756. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friborg O, Martinussen M, Rosenvinge JH. Likert-based vs semantic differential-based scorings of positive psychological constructs: a psychometric comparison of two versions of a scale measuring resilience. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;0:873–884. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polk LV. Toward a middle-range theory of resilience. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1997;19:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greene R, Galambos C, Lee Y. Resilience theory: theoretical and professional conceptualizations. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2003;8(4):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI. Family coping with health crises: The resiliency model of family stress, adjustment and adaptation. In: Danielson C, Hamel-Bissell B, Winstead-Fry P, editors. Families, Health, and Illness. New York, NY: Mosby; 1993. [Google Scholar]