Abstract

Alcohol dependence (AD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are highly prevalent and comorbid conditions associated with a significant level of impairment. Little systematic study has focused on gender differences specific to individuals with both AD and PTSD. The current study examined gender-specific associations between PTSD symptom severity, drinking to cope (i.e., reduce negative affect), drinking for enhancement (i.e., increase positive affect), and average alcohol use in a clinical sample of men (n = 46) and women (n = 46) with comorbid AD and PTSD. Results indicated that PTSD symptoms were highly associated with drinking to cope motives for both men and women but with greater drinking for enhancement motives for men only. Enhancement motives were positively associated with average alcohol quantity for both men and women, but coping motives were significantly associated with average alcohol quantity for women only. These findings suggest that for individuals with comorbid AD and PTSD, interventions that focus on reducing PTSD symptoms are likely to lower coping motives for both genders, and targeting coping motives is likely to result in decreased drinking for women but not for men while targeting enhancement motives is likely to lead to reduced drinking for both genders.

Keywords: alcohol dependence, posttraumatic stress disorder, dual diagnosis, drinking motives, gender differences

Alcohol dependence is one of the most common psychiatric disorders, second only to major depression in the United States (Kessler et al., 1994). Data from the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) demonstrated that about 14% of the general population has a lifetime history of alcohol dependence (AD; Kessler et al., 1994, 1997). Of individuals with a history of AD, the majority of men (78.3%) and women (86.0%) meet criteria for at least one other psychiatric disorder (Kessler et al., 1997). Comorbidity of alcohol use disorders with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition that may develop as a result of exposure to a traumatic event, is especially prevalent and has been well documented (e.g., Epstein, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 1998; Keane & Kaloupek, 1998; McFarlane, 1998; Stewart, 1996). For example, data from the NCS indicate that 26.2% of women and 10.3% of men with AD met criteria for PTSD (Kessler et al., 1997). Some studies have found that this co-occurrence is associated with greater clinical impairment than in individuals with either disorder alone (Ouimette, Moos, & Finney, 2000; Read, Brown, & Kahler, 2004), while others have indicated that this co-occurrence is associated with greater functional impairment (e.g., unemployment, lower income) but not greater PTSD symptom severity or alcohol use per se (Drapkin et al., 2011).

Although many studies have examined gender differences with respect to prevalence, risk factors, symptom progression, and consequences among individuals with either AD (e.g., Brady & Randall, 1999; Keyes, Grant, & Hasin, 2008; Mann et al., 2005; Pettinati et al., 2000; Randall et al., 1999) or PTSD (e.g., Breslau et al., 1997; Kessler et al., 1995; Kimerling, Ouimette, & Wolfe, 2002; Olff, Langeland, Draijer, & Gersons, 2007), few studies have focused systematically on gender differences specific to individuals with both AD and PTSD. In one such study, Sonne and colleagues (2003) examined gender differences in a clinical sample with both PTSD and AD. They found that the frequency of alcohol use and alcohol use severity assessed with the Addiction Severity Index was similar for men and women. Men did, however, report an earlier age of onset of AD, greater alcohol use intensity and craving, and more severe legal problems due to alcohol use, whereas women reported greater exposure to sexually-related traumas, greater frequency and intensity of avoidance of trauma-related thoughts and feelings, and greater social impairment due to PTSD. The authors also found that PTSD more often preceded AD among the women than the men, which to our knowledge had not been previously examined nor has it been examined since. In a more recent study with a comorbid PTSD and AD sample, negative cognitions about the self were found to be significantly related to alcohol cravings in men but not women (Jayawickreme, Yasinski, Williams, & Foa, 2011). Neither study assessed whether there were gender differences with regard to the strength of the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and drinking behavior.

Beyond these descriptive findings, few studies have examined how gender might influence relationships that are believed to be important in the presentation of these two disorders. Motives for drinking, in particular, are thought to be important factors that are relevant to the relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. Two sets of drinking motives have been conceptualized as being especially impacted by PTSD: drinking to cope (e.g., to reduce internal negative affective states) and drinking for enhancement (e.g., to increase internal positive states). There is some evidence that supports the supposition that people with PTSD symptoms may be motivated both to cope with negative affect as well as to enhance positive affect through alcohol use (e.g., Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). However, we do not know whether gender interacts with drinking motives to influence the relationships between PTSD symptoms and drinking behaviors generally, and we do not know whether drinking motives could be important in differentially tailoring treatment for women and men with comorbid PTSD and AD.

Drinking to cope has received considerable empirical attention in the context of PTSD. Studies in this area have typically found that there is a positive correlation between PTSD symptom severity and greater endorsement of drinking to cope with negative emotions (e.g., Dixon et al., 2009; O’Hare & Sherrer, 2011; O’Hare, Sherrer, Yeamen, & Cutler, 2009; Stewart, Mitchell, Wright, & Loba, 2004; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005; Yeater, Austin, Green, & Smith, 2010). This is in line with the self-medication model (Baker et al., 2004; Khantzian, 2003), which asserts that the substance is consumed to alleviate symptom-related distress and that the associated relief reinforces continued substance use (Simpson, 2003; Stewart, Conrod, Pihl, & Dongier, 1999). Notably, with the exception of Simpson (2003), all of the above studies were conducted with community samples or trauma-exposed samples, but not individuals diagnosed with PTSD, AD, or both.

Several studies have examined gender differences in drinking to cope motives. Data from the NCS demonstrated that among participants with an anxiety disorder (not necessarily PTSD), men were more likely than women to report that they drank or used drugs more than usual to help them reduce fears (Bolton, Cox, Clara, & Sareen, 2006). Similarly, data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) found that among those with an anxiety disorder other than PTSD, men were more likely than women to self-medicate with substances, although there were no gender differences on self-medicating with alcohol only (Robinson, Sareen, Cox, & Bolton, 2009). Recently, NESARC data were used to demonstrate that among individuals with lifetime PTSD, men were twice as likely to report drinking to cope as women (e.g., drink alcohol when having reactions to a stressful event; Leeies, Pagura, Sareen, & Bolton, 2010). In a study of undergraduate students, men with beliefs that alcohol has tension-reduction effects were found to have stronger relationships between PTSD symptoms and drinking than either men with lower beliefs in alcohol’s tension reduction effects or women, regardless of their tension-reduction alcohol expectancies (Hruska & Delahanty, 2012). Nonetheless, associations between PTSD symptoms and drinking to cope motives have not been examined among men and women diagnosed with both PTSD and AD. Given the finding among comorbid samples that women exhibit greater avoidance of trauma-related thoughts and feelings (Sonne et al., 2003), it is possible that women are just as likely to drink to cope as their male counterparts.

The motivation to drink for coping purposes may also be independent of the desire to turn to alcohol for enhancement, to achieve positive affect. A large literature suggests that the experience of negative and positive emotional states are qualitatively different and not simply opposites (e.g., Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995 e.g., Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 2000; Diener & Emmons, 1984). In other words, positive affect is not simply achieved by removing negative affect but involves a specific motive to seek positive emotions. This basic two-dimensional structure of affect emerges across many lines of research (Watson & Tellegen, 1985). In this way, drinking to cope with negative affect, even if successful, is not expected to necessarily lead to increased positive affect. Individuals who desire more positive affect may turn to alcohol for enhancement purposes: to achieve such positive affect independent of the motivation to drink to cope with negative feelings.

The literature on the relationship between trauma, PTSD, and enhancement motives is more sparse and has been more mixed than that on PTSD and drinking to cope motives. For example, enhancement motives partially mediated the relationship between childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and alcohol problems in a sample of women with a history of CSA (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). Although a direct relation was observed between CSA and alcohol problems, enhancement motives explained a portion of this relationship. Moreover, convivial drinking (e.g., celebrating, partying) was associated with PTSD symptoms in a survey of community clients (O’Hare et al., 2009) and mediated PTSD hyper-arousal symptoms and alcohol consumption in another sample of community mental health clients (O’Hare et al., 2011). That is, hyper-arousal symptoms were positively associated with convivial drinking, which in turn were significantly associated with quantity and frequency of alcohol use. Conversely, other studies have found that enhancement motives were not significantly associated with PTSD symptoms (e.g., Dixon et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2004). To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined gender differences in the relationship between PTSD symptoms and enhancement motives.

In addition to the association between drinking motives and PTSD symptoms, drinking motives are also typically found to be associated with drinking behavior including the amount of alcohol consumed (Cooper, 1994; Read et al., 2003). Among trauma-exposed populations, coping motives have been shown to be significantly associated with alcohol consumption (Fossos et al., 2011; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Ullman et al., 2005). In a prospective study of adult drinkers, greater drinking to cope motives led to an increased risk for first-time occurrence of AD both one year (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998) and ten years later (Beseler et al., 2008). Drinking for enhancement has also been associated with greater alcohol consumption, heavy drinking, and drinking to intoxication (Beseler, Aharonovich, & Hasin, 2011; Read et al., 2003; Schulenberg et al., 1996), and as noted above has been found to mediate the relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption (O’Hare et al., 2009). Nonetheless, drinking to cope has generally demonstrated a stronger relationship with alcohol use and related problems than has drinking for enhancement (Cooper, 1994; Cooper et al., 1992; Martens, Cox, & Beck, 2003).

Few studies have examined gender differences in the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use, and none have included a clinical sample dually diagnosed with PTSD and AD. In a sample of men and women who had alcohol use disorders, decreases in drinking to cope motives were more strongly associated with better drinking outcomes among men than among women (Timko, Finney, & Moos, 2005). These results are consistent with earlier findings that avoidant coping is more strongly related to alcohol consumption and problems in men than in women (Cooper et al., 1992; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1993). Moreover, the relationship between positive expectancies and alcohol consumption as well as various other measures of alcohol use has been found to be stronger in men than women across several studies (Armeli et al.2000; Kushner, Sher, Wood, & Wood, 1994).

Taken together, the current literature on gender differences in PTSD, drinking motives, and alcohol use suggests that PTSD symptoms are likely to be more strongly associated with coping drinking motives for men than for women, and that both coping and enhancement motives are more likely to be associated with greater alcohol use among men than among women. None of the studies to date, however, have examined these associations in clinical samples consisting of men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD. Doing so is critical due to the high prevalence of these comorbid conditions among both genders. Moreover, gender differences that have typically been reported in non-clinical samples may not apply to those with PTSD and AD, whose overall course of psychopathology might be quite different. For example, Dawson and colleagues (2010) found that women with AD had significantly greater odds than women without AD to also have internalizing disorders, externalizing disorders, as well as a combination of the two. Given the higher level of impairment among these women, it is possible that in a comorbid PTSD and AD sample, the observed gender differences for the associations among PTSD symptoms, drinking motives, and drinking are significantly different. For example, compared to men, these women may be as likely to respond to increasing severity of PTSD symptoms by drinking to cope, and the strength of their drinking to cope and drinking to enhance motives may be just as likely to be associated with their actual alcohol consumption. Because it may not be appropriate to assume that the distinct drinking motive patterns seen for non-dually disordered men and women hold for those who are dually-diagnosed, examining potential gender differences in this population is imperative.

This study examined gender differences in two sets of relationships in a sample of men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD. First, we evaluated whether gender moderated the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and both coping and enhancement drinking motives. In order to examine the unique effect of PTSD symptoms on drinking motives over and above other types of distress, we controlled for symptoms of depression. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that PTSD symptom severity would be more strongly associated with drinking to cope in men than in women. We did not have a priori hypotheses regarding how gender might affect the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and enhancement drinking motives given the lack of relevant prior literature. Second, we evaluated whether gender moderated the relationship between coping and enhancement drinking motives and alcohol use. Based on prior literature we hypothesized that both drinking to cope and enhancement motives would be more strongly associated with alcohol use in men than in women.

Method

Participants

The study sample was comprised of 92 (50% female) civilians (n = 69; 55% female) and veterans (n = 23; 35% female) with comorbid PTSD and AD who indicated a desire to abstain from or decrease alcohol use and who were part of a larger study designed to evaluate mechanisms of behavior change associated with two brief interventions, one focused on increasing capacity for experiential acceptance and one focused on learning basic cognitive restructuring skills. The treatment trial is registered through ClinicalTrials.gov (# XX; masked for review).

Participants were on average 44.75 years old (SD = 10.82), with the following ethnic background: 40% African American, 44% White, 4% Hispanic, 4% Native American, 3% reported other, 3% reported multiple ethnicities, and 1% Asian American. Most of the sample indicated that they never married (39%), while 12% reported being married or in a permanent partnership, 13% separated, 25% divorced, 4% widowed, and 3% indicated other. In terms of educational background, 22% indicated that they did not graduate high school, 16% graduated high school, 45% had some college, and 17% were college graduates or had post-graduate education. Only a small minority (15%) had full- or part-time employment. Most participants reported history of psychiatric medication management (59%) or mental health therapy (70%) of 1 or more years. Approximately half of study participants reported a history of hospitalization for substance use disorder (49%), and over one-quarter reported having been hospitalized for mental health disorders (27%). The sample also met criteria for various other substance dependence disorders in the last year. In particular, 2% met criteria for sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytic dependence, 8% for cannabis dependence, 2% for stimulant dependence, 5% for opioid dependence, 25% for cocaine dependence, 1% for hallucinagen/PCP dependence, and 1% for dependence on other drugs. Of the total sample, 56% met criteria for AD only and not for any other substance use disorders. Also, those with a diagnosis of opioid or stimulant dependence had not used these substances in at least the last month, though those with other types of dependence may have used those drugs more recently.

Gender was not significantly associated with any of the demographic variables, including age, t(90) = 1.11, p > .05; race/ethnicity, χ2(6) = 10.92, p > .05; marital status, χ2(7) = 1.47, p > .05; education, χ2(5) = 4.37, p > .05; or full- or part-time employment, χ2(1) = 3.03, p > .05. Veteran status was also not significantly associated with any of the demographic variables, including gender, χ2(1) = 2.84, p > .05; age, t(90) = 1.20, p > .05; race/ethnicity, χ2(6) = 6.20, p > .05; marital status, χ2(7) = 11.70, p > .05; education, χ2(5) = 3.98, p > .05; or full- or part-time employment, χ2(1) = 1.01, p > .05. Neither gender nor veteran status was associated with meeting criteria for any other substance dependence disorders, all ps > .05. With respect to exposure to traumatic events, women were most likely to have witnessed or experienced physical assault (87%) or sexual assault (85%), while men were most likely to have witnessed or experienced a transportation accident (89%) or physical assault (87%). Veterans were most likely to have witnessed or experienced a transportation accident (96%) or physical assault (87%), while civilians were most likely to have witnessed or experienced physical assault (87%) or assault with a weapon (73%).

Participants who met the following inclusion criteria at the initial screening and baseline assessment were eligible for the study: 1) age ≥ 18 years, 2) current DSM-IV diagnosis of AD with some alcohol use in the last two weeks, 3) current DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD, 4) capacity to provide informed consent, 5) English fluency, 6) no planned absences that they would be unable to complete six weeks of daily monitoring and study sessions (as part of the larger study), and 7) access to a telephone (as part of the larger study). In addition, individuals were excluded from the study due to the treatment outcome nature of the larger study, if they had 1) a history of delirium tremens, or 2) seizures, in order to ensure that participants would be medically safe to decrease alcohol use, 3) any methamphetamine use or opiate use or chronic treatment with any opioid-containing medications during the previous month, 4) currently taking or planning to start taking either antabuse or naltrexone, 5) exhibiting signs or symptoms of alcohol withdrawal at the time of initial consent, 6) acutely suicidal with intent/plan or present an imminent danger to others, or 7) exhibiting a psychotic disorder.

Procedure

Civilian participants were alerted to this study through advertisements placed in two community weekly newspapers that serve the greater Seattle metropolitan area. Veterans were alerted to this study opportunity via flyers posted throughout the VA medical center as well as during the treatment orientation group of the Addictions Treatment Center by VA clinic staff. Interested individuals contacted the study coordinator and underwent a telephone screening to evaluate basic inclusion/exclusion criteria. Those who were eligible were invited to attend an in-person appointment to further assess inclusion/exclusion criteria. Subsequent to providing written informed consent, participants completed a screening assessment to assess for the presence of PTSD and AD as well as a battery of self-report questionnaires (see Measures below). All of the baseline assessments were conducted by the study coordinator, who was trained on the interview measures using extensive role-plays and direct observation by the senior author. Two licensed psychologists (the first and senior author) reviewed 10% of the baseline assessments, chosen randomly, of all consenting individuals for inter-reliability of PTSD and AD diagnoses and found 100% agreement with the original assessor’s diagnostic determinations. In addition, all participants received financial compensation for completing study measures, including $30 for completing the baseline assessment.

Measures

Screening assessment

Alcohol-related medical history, suicidality and homicidality

The exclusion criteria of history of seizures or delirium tremens and current or planned use of antabuse or naltrexone during the study period were assessed via a set of interview questions compiled for the study. Suicidality was assessed with the suicide section of the Hamilton Depression Inventory (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960). Participants were also asked standard clinical questions regarding homicidality (i.e., “In the last month have you thought about harming or killing anyone?”). Participants who endorsed homicidal ideation or suicidal ideation with intent or plan were excluded from the study and thoroughly evaluated for safety.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

(SCID-1; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1995). The SCID is a widely used structured interview that assesses Axis I psychiatric history. The SCID-1 has been shown to have very good reliability (e.g., Zanarini et al., 2000) and validity (e.g., Kranzler et al., 2003). Only the “substance use disorder” and “psychotic and associated symptoms” sections of the interview were used to assess the inclusion criteria (diagnosis of alcohol dependence) and the exclusion criteria (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform disorder).

PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview Version

(PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rauthbaum, 1993). The PSS-I is a 17-item semi-structured interview that assesses current PTSD diagnostic status (APA, 1994). The PSS-I has good internal consistency, item-total correlations, and concurrent and convergent validity (Foa et al., 1993). A one-month timeframe was used to determine whether potential participants met the study inclusion criteria of current PTSD. Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .80.

Screening and baseline measure

Form-42

(Miller & Del Boca, 1994). The Form-42 was adapted from the Form-90 and was used to characterize the sample’s alcohol and drug consumption for the 6-week period prior to baseline and to ensure that participants had used alcohol in the previous two weeks to meet inclusion criteria. This method has previously been used in clinical trials and found to be a reliable method of assessing alcohol use (Tonigan, Miller, & Brown, 1997). The average number of drinks per day across the 6-week period was calculated by summing the total number of drinks consumed and dividing by the total number of days in the 6-week period (i.e., 42). Average number of drinks per day, served as an outcome variable, and ranged from less than 1 to 22 drinks per day on average (M = 6.32, SD = 5.05).

Baseline assessment

PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers & Ford, 1996)

The PCL-C is a well-validated 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms consistent with the DSM-IV (APA, 1994). Participants endorse each symptom from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), with scores ranging from 17 to 85. The total score of the PCL-C was used to assess PTSD symptom severity. The PCL-C has demonstrated high levels of diagnostic accuracy (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996), as well as good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003). Moreover, the PCL has demonstrated high convergent validity with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (r = .93, Blanchard et al., 1996). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .86.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001)

The PHQ-9 consists of 9 items that assess how often the participant has been bothered by a range of depressive symptoms from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) over the last two weeks. It has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of depression severity (Kroenke et al., 2001; Wittkampf et al., 2007). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994, Cooper et al., 1995)

The DMQ-R consists of 20 items assessing four distinct drinking motives for alcohol use identified in Cooper’s (1994) model. Participants rate each item on how frequently it motivates them to drink alcohol from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). The average scores of the 5-item subscales assessing coping motives (drinking to alleviate negative emotions) and enhancement motives (drinking to enhance positive emotions) were used in the present study. The DMQ-R has good construct and convergent validity and internal reliability (α’s range from .84 to.88; Cooper, 1994; MacLean & Lecci, 2000). In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for coping motives was .78 and for enhancement motives was .72.

Statistical Analysis

Prior to our main analyses, we assessed for non-normality in the dependent variables (i.e., drinking motives in the first analysis and average alcohol quantity per day in the second analysis). Skew and kurtosis were within an acceptable range of normality (within +/− 2.0). We conducted independent t-tests to examine gender differences in the main study variables as well as differences by veteran status, and examined correlations to assess associations between major study variables at the bivariate level. We included veteran status as a covariate in models predicting average alcohol quantity. We also included the PHQ-9 as a covariate in models predicting drinking motives in order to examine whether PTSD symptoms were uniquely predictive of drinking motives beyond another type of distress.

Prior to conducting regression analyses, continuous predictors were centered to reduce the threat of artifactual multicollinearity among these variables (Aiken & West, 1991). We then conducted four hierarchical regression analyses, where covariates and main effects were entered on the first step and the interaction term on the second step. The first two analyses predicted coping and enhancement motives as a function of PTSD symptom severity, gender, and their interaction, controlling for the effects of depression. The latter two regression analyses predicted average alcohol quantity per day as a function of coping motives, gender, and their interaction; and enhancement motives, gender, and their interaction, controlling for veteran status.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Women and men did not significantly differ from one another on PTSD symptom severity, depression scores, coping motives, enhancement motives, or average drinking, all ps > .05 (see Table 1). There were also no significant differences by veteran status on PTSD symptom severity, t(88) = −0.69, p > .05, coping motives, t(88) = 0.87, p > .05, or enhancement motives, t(88) = 1.06, p > .05. There was a significant difference between veterans (M = 15.83, SD = 6.86) and civilians (M = 13.63, SD = 5.05) on depression scores, t(89) = −1.64, p = .01, as well as on average alcohol quantity, M = 4.62, SD = 3.08 for veterans and M = 6.90, SD = 5.47 for civilians, t(87) = 1.89, p = .02. As a result, veteran status was included as a covariate in analyses predicting average alcohol quantity.

Table 1.

Gender Differences and Correlations among Main Study Variables

| Variable | Men M (SD) |

Women M (SD) |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD severity | 57.20 (11.23) | 55.04 (12.74) | ||||

| 2. Depression | 14.04 (5.28) | 14.33 (5.96) | .59*** | |||

| 3. Coping motives | 3.34 (1.01) | 3.50 (0.94) | .44*** | .41*** | ||

| 4. Enhancement motives | 3.31 (0.97) | 3.08 (1.00) | .04 | −.02 | .45*** | |

| 5. Average alcohol quantity | 7.29 (5.22) | 5.36 (4.73) | .06 | .03 | .17 | .26* |

Note. Average alcohol quantity was derived from the Form-42 as the average number of drinks per day over the previous six weeks.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Bivariate correlations showed that the two drinking motives (coping and enhancement) were significantly correlated with one another. Moreover, both PTSD symptom severity and depression scores were significantly and positively associated with coping motives, but not with enhancement motives or average alcohol quantity. Average alcohol quantity was significantly associated only with enhancement motives. Depression was significantly correlated with PTSD symptom severity and coping motives.

Regression Analyses

Factors associated with drinking motives

Coping drinking motives

The first moderated regression analysis examined associations between PTSD severity, gender, and their interaction with coping motives, after controlling for the effects of depression (see Table 2). The set of predictors accounted for 21% of the variance in coping motives. There was a main effect of PTSD symptom severity such that higher levels of PTSD symptom severity were significantly associated with greater drinking coping motives. Depression symptoms, gender, and the interaction between PTSD severity and gender were not significantly associated with coping drinking motives.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses of PTSD Severity and Gender on Drinking Motives

| B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping motives | ||||||

| Step 1 (main effects) | ||||||

| Depression | .04 | .02 | .22 | .21*** | 8.72*** | |

| PTSD severity | .03 | .01 | .31** | |||

| Gender | .20 | .19 | .10 | |||

| Step 2 (main effects and interaction) | ||||||

| Depression | .04 | .02 | .22 | .21*** | .01 | 1.33 |

| PTSD severity | .04 | .01 | .44** | |||

| Gender | .20 | .18 | .10 | |||

| PTSD severity x gender | −.02 | .02 | −.17 | |||

| Enhancement motives | ||||||

| Step 1 (main effects) | ||||||

| Depression | −.01 | .02 | −.06 | −.02 | .45 | |

| PTSD severity | .01 | .01 | .06 | |||

| Gender | −.21 | .21 | −.11 | |||

| Step 2 (main effects and interaction) | ||||||

| Depression | −.01 | .02 | −.06 | .04 | .06* | 5.91* |

| PTSD severity | .03 | .02 | .35* | |||

| Gender | −.21 | .21 | −.11 | |||

| PTSD severity x gender | −.04 | .02 | −.39* | |||

Note. Gender coded such that men = 0 and women = 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

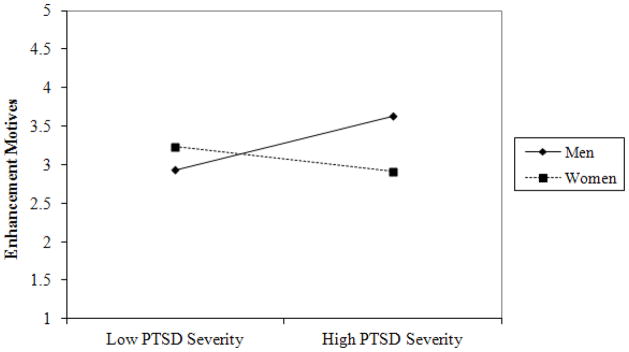

Enhancement coping motives

After controlling for depression, the combination of PTSD severity, gender, and their interaction only accounted for 4% of the variance in enhancement motives. In Step 1 of the regression, depression scores, PTSD severity, and gender were not significant, nor was the overall model, F(3, 85) = 0.45, p > .05. Although the overall regression model remained non-significant in Step 2, overall F(4, 84) = 1.83, p > .05, the significant interaction between PTSD and gender added a significant amount of explained variance in enhancement motives (ΔF = 5.91, p = .02). For women, levels of PTSD symptom severity were unrelated to enhancement motives, r = −.21, p > .05, but higher levels of PTSD symptoms were associated with greater enhancement motives among men, r = .30, p < .05; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PTSD Severity by Gender for Enhancement Motives

Note. The zero-order correlation between PTSD symptom severity and enhancement motives for women was r = −.21, p > .05, and for men it was r = .30, p < .05.

Factors associated with average alcohol quantity

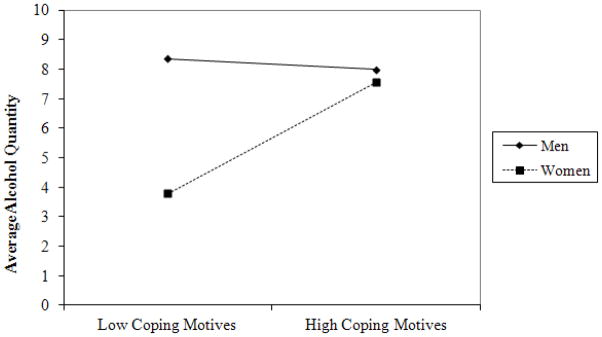

Next, we examined associations between coping motives, gender, and their interaction on average alcohol quantity, adjusting for veteran status (see Table 3). Veteran status, coping motives, gender, and the coping motives x gender interaction accounted for 12% of the variance in alcohol use. In Step 1 of the regression, the overall model was significant and gender and veteran status but not coping motives had an effect. When the interaction term was entered on Step 2, gender but not veteran status remained significant as a main effect but was superseded by its significant interaction with coping motives. This interaction suggested that for women, higher coping motives were associated with higher levels of average alcohol quantity, r = .42, p < .01, while for men coping motives were unrelated to average alcohol quantity, r = −.03, p > .05 (see Figure 2).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses of Drinking Motives and Gender on Average Alcohol Quantity

| B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average alcohol quantity | ||||||

| Coping motives model | ||||||

| Step 1 (main effects) | ||||||

| Veteran status | −2.44 | 1.21 | −.21* | .09* | 3.75* | |

| Coping motives | .86 | .54 | .16 | |||

| Gender | −2.52 | 1.05 | −.25* | |||

| Step 2 (main effects and interaction) | ||||||

| Veteran status | −2.33 | 1.19 | −.20 | .12** | .04* | 4.09* |

| Coping motives | −.19 | .74 | −.04 | |||

| Gender | −2.50 | 1.03 | −.25* | |||

| Coping motives x gender | 2.15 | 1.06 | .29* | |||

| Enhancement motives model | ||||||

| Step 1 (main effects) | ||||||

| Veteran status | −2.27 | 1.21 | −.20 | .11** | 4.44** | |

| Enhancement motives | 1.09 | .52 | .22* | |||

| Gender | −2.16 | 1.04 | −.22* | |||

| Step 2 (main effects and interaction) | ||||||

| Veteran status | −2.24 | 1.22 | −.19 | .10* | .00 | .07 |

| Enhancement motives | .94 | .76 | .19 | |||

| Gender | −2.16 | 1.05 | −.22* | |||

| Enhancement motives x gender | .28 | 1.05 | .04 | |||

Note. Veteran status coded such that 0 = no and 1 = yes. Gender coded such that men = 0 and women = 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Coping Motives by Gender for Average Alcohol Quantity

Note. The zero-order correlation between PTSD symptom severity and enhancement motives for women was r = .42, p < .01, and for men it was r = −.03, p > .05.

The combination of veteran status, enhancement motives, gender, and the interaction between enhancement motives and gender accounted for 10% of the variance in alcohol use. In Step 1 of the regression, the overall model was significant and both enhancement motives and gender had significant main effects. When the interaction term was entered on Step 2, the overall regression remained significant but the interaction term was non-significant and did not add a significant amount of variance to the model. Thus, the model in Step 1 was considered the final model, wherein both greater enhancement motives predicted greater drinking and men reported greater average alcohol quantity than women.

Discussion

This study examined gender differences between PTSD symptom severity and drinking motives and between drinking motives and average alcohol consumption in a clinical sample with comorbid PTSD and AD. Previous research with mostly community or clinical samples with either PTSD or AD (but not both) largely suggested that symptoms of distress are more strongly associated with coping motives for men (e.g., Bolton et al., 2006; Leeies et al., 2010), and similarly that enhancement motives are more strongly associated with alcohol use for men (e.g., Armeli et al., 2000; Timko et al., 2005). Examining whether such associations are similar or different among men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD is critical, given the high prevalence of these co-occurring conditions among men and women and potential implications for treatment.

Unlike previous studies that have documented associations between PTSD symptoms and drinking in non-clinical samples (e.g., Messman-Moore, Ward, & Brown, 2009; Simons et al., 2005), there was not a significant association between PTSD symptoms and average alcohol quantity in our sample. One possible explanation for this null finding is a potential ceiling effect, where individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD are drinking at relatively high levels such that the effect of PTSD on average alcohol quantity is not observed. Moreover, although many studies document an association between PTSD symptoms and increased alcohol use, several other studies investigating PTSD and drinking among women failed to find such an association (Testa, Livingston, & Hoffman, 2007; Ullman et al., 2005). This suggests that the relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption may differ depending on what type of sample is under study and also may be better understood as a function of drinking motives or alcohol expectancies (Ullman et al., 2005).

With respect to the relationship between PTSD symptoms and drinking motives, our findings indicated that PTSD symptom severity was positively associated with endorsement of drinking to cope for both men and women. In other words, men and women who reported greater PTSD symptoms also reported greater motives to drink to cope. Notably, PTSD symptoms—rather than depression symptoms—drove this relationship. These findings are in contrast with other studies that have found that PTSD symptoms are associated with coping motives for men but not for women. This discrepancy could be due to differences in samples. These studies generally did not include men and women diagnosed with both PTSD and AD and thus those results may not apply to this population.

On the other hand, greater PTSD symptoms were associated with greater endorsement of enhancement drinking motives for men but not for women, although the overall model was not significant. Developmental researchers have suggested that men have more difficulty with affect regulation than do women (Weinberg, Tronick, Cohn, & Olson, 1999). Although we did not examine individual PTSD symptom clusters, one potential explanation is that this observed association is related to symptoms of emotional numbing and a greater desire among men than among women to feel positive emotions that may be dampened by PTSD. Nonetheless, it is important to note that while the interaction between PTSD symptom severity and gender was significant, it explained very little variance in enhancement motives, and the overall model was non-significant. Thus, PTSD symptoms do not sufficiently explain enhancement motives among men or women, and future research is needed both to more fully understand the nature of this association as well as additional factors that are associated with such motives.

Also contrary to initial hypotheses, women who reported greater coping motives also reported more drinking. There was no such association between coping motives and drinking for men; their drinking was relatively high and stable compared to women’s drinking regardless of their drinking-to-cope motives (see Figure 2). Although this is in contrast to previous findings that men, more than women, tend to increase their drinking in response to coping motives (e.g., Cooper et al., 1992; Frone et al., 1993; Timko et al., 2005), it may not be altogether surprising in the current sample of individuals diagnosed with AD whose drinking rates are already high. We also found that enhancement motives were positively associated with drinking quantity for the overall sample at the bivariate level and the final multivariate model, suggesting that these reasons for drinking may be important to consider in understanding the functions of alcohol consumption among both men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD.

Although the present investigation was not a direct test of the self-medication model, the results provide both support for aspects of this model and important possible refinements of the model. Of note, increased PTSD severity was associated with a greater motivation to drink to cope for both men and women. Greater coping motives were also associated with increased drinking for women but not for men. Together, these findings suggest that women’s alcohol consumption may be particularly linked to a desire to cope with PTSD symptoms, which may be germane to previous research indicating that PTSD more often precedes AD in women than men and that women report greater avoidance of trauma-related thoughts and feelings than do men (Sonne et al., 2003). This suggests that targeting PTSD symptoms and drinking to cope motives in women may be likely to result in a decrease in their alcohol consumption. However, the picture appears to be somewhat more complex when the frame is expanded to include information on enhancement drinking motives. As noted previously, men with greater PTSD severity, but not women, reported greater enhancement drinking motives. Greater enhancement motives and male gender were both directly correlated with greater drinking in this comorbid sample. These findings suggest that in addition to the traditional self-medication hypothesis that is reflected in the present findings on PTSD symptoms and drinking to cope motives, drinking for enhancement purposes is important to consider as well.

Gender differences in associations between PTSD and drinking motives and between drinking motives and alcohol quantity may reflect broader differences in personality profiles that may impact when, how, and why those with PTSD choose to drink. Specifically, research has suggested distinct personality-based subtypes of posttraumatic adjustment: an “externalizing” subtype characterized by impulsivity, disinhibition, Cluster B personality disorder features, and substance dependence; and an “internalizing” subtype characterized by low positive temperament, high rates of major depressive disorder, and schizoid and avoidant personality features (Miller & Resick, 2007). Despite the suggestion that those with AD fit into the “externalizing” personality type (Dawson et al., 2010), a longitudinal study of post deployment National Guard soldiers (88% male) found that higher PTSD symptom severity and lower levels of positive emotionality (i.e., internalizing subtype) was associated with the development of AD following deployment, whereas higher levels of negative emotionality and disconstraint (i.e., externalizing subtype) were predictive of the development of AD prior to deployment (Kehle et al., 2012). Thus, it is possible that some individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD may be best characterized by the externalizing subtype and others by the internalizing subtype depending on personality traits. Drinking motives may also potentially play a role given their associations with negative and positive affect, although this has yet to be examined. Our findings suggest that perhaps women, whose PTSD symptoms were associated with greater coping motives and these motives were, in turn, associated with greater drinking, may be better characterized by the internalizing subtype; wheras men, whose PTSD was associated with coping motives and to some extent with enhancement motives, could be characterized by the internalizing and/or externalizing subtypes. Future research should assess personality traits along with drinking motives to evaluate whether there are indeed divergent internalizing and externalizing subtypes among men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD.

Several implications for clinical intervention should be noted. Based on the findings regarding relationships between PTSD and coping motives, interventions that focus on reducing PTSD symptoms may also result in decreasing the motivation to drink as a way of coping with negative affect for both men and women with diagnoses of both PTSD and AD. This may help to explain studies that have found that exposure treatments for PTSD symptoms also decrease drinking behavior for those with PTSD and AD (Coffey, Stasiewicz, Hughes, & Brimo, 2006). In addition to providing empirically-supported treatments for PTSD and AD, treatment might be augmented by a direct focus on the impact of one’s personal drinking motives. Specifically, therapists might work with patients to identify when they may be at increased likelihood of feeling motivated to drink to cope or to enhance positive affect in response to PTSD symptoms, which would be consistent with strategies already included in Relapse Prevention for alcohol problems (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2005). Moreover, education about the link between both drinking-to-cope and enhancement motives and alcohol consumption among women and enhancement motives and alcohol consumption among men should be provided. Often the focus in therapeutic interactions is on how to reduce one’s level of current distress. However, it appears as though alcohol consumption is also linked to a desire to increase positive affect among women and men who are diagnosed with PTSD. Thus, therapists should also assist patients to identify and implement healthier coping strategies for achieving positive affect other than by consuming alcohol. For example, Behavioral Activation (Jakupcak et al., 2006; Martell, Addis, & Jacobson, 2001) strategies aimed at increasing contact with positive reinforcers could be explored as a way to decrease reliance on alcohol for increasing positive affect.

Results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Although our sample of men and women diagnosed with both PTSD and AD is a strength of the present investigation, it also limits the ability to generalize results beyond those with these comorbid disorders. In addition, 44% of our sample met criteria for substance abuse disorders in addition to AD, with 25% reporting cocaine dependence in the last year. This is not particularly unusual, as cocaine abuse or dependence disorders have been found to be the most strongly associated of the specific drug disorders with alcohol use disorders (Stinson et al., 2006). Nonetheless, we only assessed motives for drinking alcohol and not motives to use other drugs; it is possible that PTSD symptoms may influence motives to use other substances differently than drinking motives, and substances other than alcohol may have been used for coping or enhancement motives, both of which may differ by gender. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we did not examine a full mediational model including PTSD symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use by gender, which would have provided a more direct test of the self-medication hypothesis. Moreover, the relationship between PTSD symptoms and coping motives could be bidirectional, such that increased motivation to drink to cope could lead to an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms. Additionally, PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior in the current investigation represent average levels over a period of several weeks. Future research with longitudinal designs and a more fine-grained assessment of PTSD and alcohol use is needed to continue to address these important associations and to determine how these relationships may unfold over time. This may be particularly relevant for a sample of individuals diagnosed with comorbid PTSD and AD whose symptoms and drinking levels may be high overall but still are likely fluctuate from day-to-day.

The present research builds upon the existing literature by examining the influence of gender on associations between PTSD symptoms and drinking motives, and drinking motives and alcohol consumption among men and women with both PTSD and AD. When gender differences are examined among a dually-diagnosed clinical sample, a different picture emerges than what is typically presented in the literature. Women’s PTSD symptoms, as well as men’s, were significantly associated with drinking to cope motives. For women, but not men, these motives were also associated with increased alcohol consumption. On the other hand, enhancement motives were significantly correlated with alcohol consumption for the overall sample. Because women and men with PTSD and AD may respond differently to PTSD symptom severity, as well as react differently to motives to drink, interventions that consider these gender-sensitive associations may result in greater efficacy for those seeking treatment.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) 1R21AA17130 as well as by resources from the University of Washington, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington, and Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Washington or of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Carney MA, Tennen H, Affleck G, O’Neil T. Stress and alcohol use: A daily process examination of the stressor-vulnerability model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:979–994. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Aharonovich E, Hasin DS. The enduring influence of drinking motives on alcohol consumption after fateful trauma. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1004–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J, Cox B, Clara I, Sareen J. Use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000244481.63148.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22:241–252. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1044–1048. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR, Hughes PM, Brimo ML. Trauma-focused imaginal exposure for individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Revealing mechanisms of alcohol craving in a cue reactivity paradigm. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:425–435. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059– 1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.4.2.123.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Moss HB, Li TK, Grant BF. Gender differences in the relationship of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology to alcohol dependence: Likelihood, expression and course. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA. The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:1105–1117. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.47.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Ham LS, Felder MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapkin ML, Yusko D, Yasinski C, Oslin D, Hembree EA, Foa EB. Baseline functioning among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;41:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. PTSD as a mediator between childhood rape and alcohol use in adult women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:223–234. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fossos N, Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Lindgren KP, Hove MC. Coping motives as a mediator of the relationship between sexual coercion and problem drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Relationship of work–family conflict, gender, and alcohol expectancies to alcohol use/abuse. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1993;14:545–558. doi: 10.1002/job.4030140604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska B, Delahanty DL. Application of the stressor vulnerability model to understanding posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol-related problems in an undergraduate population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027584. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Roberts LJ, Martell C, Mulick P, Michael S, Reed R, Balsam KF, Yoshimoto D, McFall M. A pilot study of behavioral activation for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:387–391. doi: 10.1002/jts.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickreme N, Yasinski C, Williams M, Foa EB. Gender-specific associations between trauma cognitions, alcohol cravings, and alcohol-related consequences in individuals with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;26:13–19. doi: 10.1037/a0023363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Kaloupek DG. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in PTSD: Implications for research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;12:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle SM, Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Meis LA, Arbisi PA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA. Predictors of postdeployment alcohol use disorders in National Guard soldiers deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:42–50. doi: 10.1037/a0024663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM–III–R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Esleman S, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:2–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis revisited: The dually diagnosed patient. Primary Psychiatry. 2003;10:47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Wofle J. Gender and PTSD. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, Blomquist O, Oncken C, Petry N, Feinn R. Targeted naltrexone for early problem drinkers. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;23:294–304. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200306000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK. Anxiety and drinking behavior: Moderating effects of tension-reduction alcohol outcome expectancies. Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:852–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeies M, Pagura J, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:731–736. doi: 10.1002/da.20677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:83–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Ackermann K, Croissant B, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Diehl A. Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: Are women more vulnerable? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000164376.69978.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems. In: Marlatt GA, Donovan DM, editors. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York, NY: W W Norton & Co; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Cox RH, Beck NC. Negative consequences of intercollegiate athlete drinking: The role of drinking motives. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:825–828. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane A. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):813–826. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM, Brown AL. Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Resick PA. Internalizing and externalizing subtypes of female sexual assault survivors: Implications for the understanding of complex PTSD. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, Sherrer M. Drinking motives as mediators between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol consumption in persons with severe mental illness. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:465–469. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, Sherrer MV, Yeamen D, Cutler J. Correlates of PTSD in male and female community clients. Social Work in Mental Health. 2009;7:340–352. doi: 10.1080/15332980802052373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BPR. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Moos RH, Finney JW. Two-year mental health service use and course of remission in patients with substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:247–253. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Rukstalis M, Luck GL, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP. Gender and psychiatric comorbidity: Impact on clinical presentation and alcohol dependence. The American Journal on Addictions. 2000;9:242–252. doi: 10.1080/10550490050148071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: A gender comparison. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:252–260. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J, Brown P, Kahler C. Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders: Symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Sareen J, Cox BJ, Bolton J. Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Jacobs GA, Meyer D, Johnson-Jimenez E. Associations between alcohol use and PTSD symptoms among American Red Cross disaster relief workers responding to the 9/11/2001 attacks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:285–304. doi: 10.1081/ADA-200047937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL. Childhood sexual abuse, PTSD, and the functional roles of alcohol use among women drinkers. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:249–270. doi: 10.1081/JA-120017248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychological and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne SC, Back SE, Zuniga CD, Randall CL, Brady KT. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12:412–423. doi: 10.1080/10550490390240783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Conrod P, Pihl R, Dongier M. Relations between posttraumatic stress symptom dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance-abusing women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:78–88. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.13.2.78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Mitchell TL, Wright KD, Loba P. The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair Flight 111 airline disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States. Alcohol Research and Health. 2006;29:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Hoffman JH. Does sexual victimization predict subsequent alcohol consumption? A prospective study among a community sample of women. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2926–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Finney JW, Moos RH. The 8-year course of alcohol abuse: Gender differences in social context and coping. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:612–621. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000158832.07705.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of the Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1997;58:358–364. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Tellegen A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:219–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Ford J. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S, PCL-M, PCL-PR) In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EA, Cohn JF, Olson KL. Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:175–188. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkampf KA, Naeije L, Schene AH, Huyser J, van Weert HC. Diagnostic accuracy of the mood module of the Patient Health Questionnaire: A systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeater EA, Austin JL, Green MJ, Smith JE. Coping mediates the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and alcohol use in homeless, ethnically diverse women: A preliminary study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:307–310. doi: 10.1037/a0021779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]