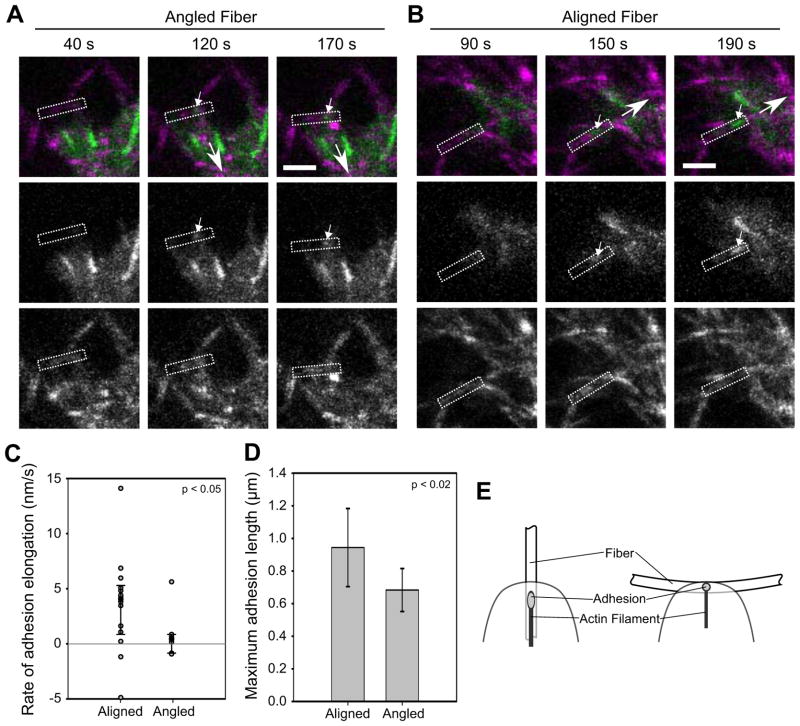

Figure 5. Local fiber orientation guides adhesion growth.

U2OS cells expressing GFP-paxillin (green) were cultured in 2 mg/ml bovine collagen matrices (magenta). (a–b) Representative image series: (a) Formation of an adhesion (small arrow) on a fiber (rectangle) at an angle to the direction of translocation (large arrow). The adhesion forms but does not increase in size (Supplemental Movie 4). Bar, 5 μm. (b) Analogous image series for an adhesion forming on a fiber parallel to the direction of translocation. The adhesion elongates (Supplemental Movie 5). (c) Dot plot of slopes from plots of adhesion length over time. Adhesions on aligned fibers predominately elongated, while those on angled fibers did not (rate ~0). The distributions are significantly different (p < 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; n = 14 and 7 adhesions for aligned and angled, respectively). (d) The maximum length of adhesions on aligned fibers was greater than on angled fibers (p < 0.02, t-test; errorbars, s.d.; same cells as (c)). (e) Diagram of how fiber orientation might affect adhesion growth. A fiber oblique to the direction of translocation could limit adhesion growth by offering less resistance (e.g. by bending in response to pulling) and/or by presenting less adhesive area. In contrast, a parallel fiber offers more contiguous area and potentially greater stiffness.