Abstract

Remembering persisting objects over occlusion is critical to representing a stable environment. Infants remember hidden objects at multiple locations and can update their representation of a hidden array when an object is added or subtracted. However, the factors influencing these updating abilities have received little systematic exploration. Here we examined the flexibility of infants’ ability to update object representations. We tested 11-month-olds in a looking-time task in which objects were added to or subtracted from two hidden arrays. Across five experiments, infants successfully updated their representations of hidden arrays when the updating occurred successively at one array before beginning at the other. But when updating required alternating between two arrays, infants failed. However, simply connecting the two arrays with a thin strip of foam-core led infants to succeed. Our results suggest that infants’ construal of an event strongly affects their ability to update memory representations of hidden objects. When construing an event as containing multiple updates to the same array, infants succeed, but when construing the event as requiring the revisiting and updating of previously attended arrays, infants fail.

Keywords: memory, cognitive development, memory and attention, infants, objects

Our visual input contains dozens of interruptions each minute, including eye blinks, shifts in head or eye position, and surfaces occluding other surfaces. Yet we experience the world in terms of continuously persisting objects (Baillargeon, 2008; Hood & Santos, 2009; Scholl, 2001). Experiencing persisting objects is a feat not only because of changes to visual input, but also because of changes in the environment itself. Objects change their spatial locations, become obscured by other objects, and sometimes acquire new properties. Even bombarded by these challenges, representing persisting objects usually feels effortless.

Much research suggests that the abilities underlying object representation are in place from early in development. Even with interruptions in perceptual contact, infants perceive objects as persisting in time and space (Baillargeon, 2008; Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985; Hood & Willatts, 1986). In addition to maintaining object representations in memory (i.e., in the absence of current perceptual input), infants can mentally manipulate representations of hidden objects to reflect dynamic changes to a scene. For example, 5-month-olds can update a representation of a hidden array to reflect addition or subtraction of an object. When infants saw an object hidden by a screen and then saw a second object added behind the same screen, they expected to see two objects when the screen was lifted, as demonstrated by their increased looking at the unexpected outcomes of one or three objects relative to the expected outcome of two objects (Feigenson, Carey & Spelke, 2002b; Koechlin, Dehaene & Mehler, 1997; Simon, Hespos & Rochat, 1995; Wynn, 1992). Similarly, infants can accurately update their representation of a hidden 2-object array when one object is subtracted from it (Feigenson et al., 2002b; Koechlin et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1995; Wynn, 1992). Although it is clear that a variety of factors influence infants’ success or failure at such occluded-object tasks, including which dependent measure is chosen (Fischer & Bidell, 1991), extant studies support the view that at least under some circumstances, infants maintain and update representations of hidden objects.

Infants’ updating abilities also extend to more complex scenes containing multiple occluded arrays. For example, infants of 8 months and older remembered objects hidden behind two spatially separated screens when one object was hidden behind one screen and then a second object was hidden behind the other (Huntley-Fenner, Carey & Solimando, 2002; Káldy & Leslie, 2003, Uller, Carey, Huntley-Fenner & Klatt, 1999). And 10- to 12-month-old infants who saw a cracker hidden in one bucket and two crackers sequentially hidden in another bucket spontaneously chose to approach the bucket containing the larger quantity. Doing so required updating representations of the contents of each bucket as the hiding events occurred, maintaining the resulting object representations in memory, and comparing them to determine which array had more (Cheries, Mitroff, Wynn, & Scholl, 2008; Feigenson & Carey, 2003, 2005; Feigenson, Carey, & Hauser, 2002a; vanMarle, 2012).

This research shows that infants can mentally update representations of hidden arrays across multiple spatial locations. This ability undoubtedly serves infants well as they interact with and learn about their dynamic surroundings. However, less well understood are the limits of early abilities to maintain and update object representations. Infants in the cracker choice experiments saw all objects placed sequentially into one hiding location before seeing any objects in the other location. For example, two crackers were hidden in a bucket on the right, followed by a cracker hidden in a bucket on the left. Infants could mentally update their representation of the entire contents of the right-hand bucket before forming any representations of objects on the left. The same “orderliness” applies to the looking-time studies described earlier. Either infants saw all of the objects placed in the first spatial location before seeing any objects at the second location (Huntley-Fenner et al., 2002; Káldy & Leslie, 2003; Uller et al., 1999), or infants updated object representations at just a single location (Feigenson et al., 2002b; Koechlin et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1995; Wynn, 1992). These findings leave open the question of whether infants also can represent events that are less orderly, in which objects appear unpredictably and representations of hidden arrays must be revisited and re-updated as events unfold.

Changes in task complexity can shift up or down the age at which a particular cognitive ability is observed (Bidell & Fischer, 1992). However, to our knowledge, just one previous study has examined the effect of increasing a particular type of task complexity—the predictability of dynamic updates—on infants’ representational abilities. In that investigation, infants saw events in which objects were added to hidden arrays in an unpredictable order, and their memory for the hidden objects was probed using the cracker choice method (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009). For example, instead of seeing crackers placed in buckets in succession (Cheries et al., 2008; Feigenson & Carey, 2005; Feigenson et al., 2002a; vanMarle, 2013), infants saw an alternating presentation of one cracker hidden in the first location, one cracker hidden in the second location, then one more cracker placed in the first location. Although the same total number of crackers had been presented as in the condition in which infants succeeded (Cheries et al., 2008; Feigenson & Carey, 2003, 2005; Feigenson et al., 2002a; vanMarle, 2013), infants chose randomly between the two locations (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009). Even with appropriate controls for event duration, presentation complexity, and number of hand movements in the presentation, infants failed across several conditions in which objects were hidden in alternation across two locations; yet they succeeded when objects were hidden in succession at one location before any objects were presented at the other location.

The performance pattern observed by Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009) shows that infants have difficulty altering a representation of an object array following intervening events that involve other hidden objects. This suggests that infants’ representations of hidden object arrays may be “frozen” or difficult to update once infants are no longer attending at that location. In Feigenson and Yamaguchi’s task, infants successfully stored a representation of a hidden cracker in the first array and another one in the second array. But they apparently were unable to return to the first array and alter it by mentally adding further objects. Their difficulty may parallel updating limitations observed in working memory tasks with adults. However, many open questions remain regarding infants’ updating abilities.

First, infants’ difficulty in updating memory representations may be specific to the cracker choice paradigm. Several unique aspects of that paradigm make unclear the generality of infants’ difficulty updating object representations. First, we know infants choose which array to approach based on continuous quantity (i.e., they choose the greater total area summed across all of the crackers in each hiding location; Feigenson et al., 2002a). This raises the possibility that infants failed to update because they were unable to sum area across objects not presented in direct temporal succession. Thus, infants might update successfully in a task less likely to trigger summation across individual object representations (e.g., in a task that does not involve food items). Second, the cracker task requires infants to perform an ordinal comparison of the two remembered arrays and then to choose to approach one of them. This raises the possibility that infants might succeed if not required to ordinally compare two arrays or if allowed to demonstrate their knowledge via a more implicit measure. Third, the cracker choice task involves just a single trial (Cheries et al., 2008; Feigenson & Carey, 2005; Feigenson et al., 2002a; vanMarle, 2013). Infants’ failure to update a working memory representation may have been driven by unexpectedly having to re-attend to the first array. Thus their performance might improve if given more trials. For these reasons it is worthwhile to investigate infants’ updating abilities using non-food objects, a less demanding looking-time task, and multiple trials.

Further exploration is also needed of the factors that cause infants difficulty in updating. Infants in Feigenson and Yamaguchi’s study failed in updating representations only when required to alternate updates across two arrays. Apparently, representing an update as changing a currently attended array, as opposed to a new array, played a critical role in infants’ success. In the present studies we tested this idea directly. We hypothesized that seeing two spatially separated hiding locations causes infants to construe the scene as containing two distinct arrays and thus to fail to perform alternating updates between the two arrays. Thus, creating a physical link between the two locations may cause infants to construe the scene as containing a single array, allowing infants to successfully represent the outcome of the alternating updates.

We also asked whether infants’ updating difficulties are specific to the event of adding objects to an existing memory representation. Previous work only tested infants’ ability to mentally add objects to a remembered array, using an alternating presentation (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009). Here we asked whether the same updating costs are observed when infants mentally subtract items from a remembered array in alternation.

1. Experiment 1

We began with a task that did not require updating across alternating locations. We tested 11-month-olds’ ability to represent two arrays containing a total of three hidden objects. Infants saw two objects hidden in direct succession behind one screen and one object hidden behind the other screen. The screens were placed onstage before the objects, thereby requiring that the object arrays be represented entirely in memory (for discussion of this “screen first” procedure vs. an “object first” procedure, see Uller et al., 1999). Immediately after the last object was hidden, the screens were removed to reveal either the expected outcome of three objects or the unexpected outcome of just two objects. If infants can successfully update their working memory representation of what was hidden in each array, they should look longer at outcomes revealing two objects than at outcomes revealing three. We chose to test infants’ memory for the number of objects that had been hidden rather than for objects’ features or locations because previous work has shown that remembering an object’s existence is easier than remembering its identity (Kibbe & Leslie, 2011; Zosh & Feigenson, 2012), or remembering which object went where (Mareschal & Johnson, 2003; Newcombe, Huttenlocher, & Learmonth, 1999). Probing memory for objects’ existence therefore served as a liberal test of infants’ updating abilities.

1.1 Method

1.1.1 Participants

Participants were 11-month-olds because infants of this age have been shown to successfully represent three hidden items in memory (Feigenson & Carey, 2003, 2005; Feigenson et al., 2002a; Ross-Sheehy, Oakes, & Luck, 2003). Furthermore, the one previous investigation of infants’ ability to perform alternating updates also tested 11-month-olds (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009), allowing for comparison between studies.

Eighteen full-term infants (10 boys) participated. Their mean age was 11 months, 14 days (range 11 months, 1 day to 11 months, 29 days). Six additional infants were excluded (3 for fussiness, 1 for sibling interference, 2 for experimenter error).

1.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

Infants sat in a highchair approximately 95cm from a black wooden puppet stage. The stage was 40cm high, 129cm wide, and 50cm deep, with a black curtain that could be lowered to cover the stage entirely. A small video camera mounted within the stage provided a view of infants’ faces and a wall-mounted camera behind infants captured a view of the stage. Both images were recorded digitally and were viewed live in an adjacent room by a trained observer who was unaware of experimental condition. An experimenter who was concealed behind the puppet stage inserted and removed objects from the stage floor and could see whether infants were watching the presentation events via a hidden television monitor.

Two black foam-core screens (16cm high by 25cm wide) with hidden ledges (10cm deep) served to hide the objects. The stimulus objects were three identical green and white balls (9cm diameter) decorated with colorful dots. Squeezing the balls produced a squeaking sound that was used to draw infants’ attention each time an object was placed on stage.

1.1.3 Procedure

Parents sat out of view behind infants and were instructed to refrain from any interaction. Classical music was played quietly throughout the experiment in order maintain infants’ interest and to mask the sounds produced by placing the objects on the stage.

Baseline trials

The experiment began with one 2-Object and one 3-Object baseline trial to measure infants’ initial preference to look at arrays containing two vs. three objects (Figure 1A). The same stimulus objects were used throughout the baseline and test trials. For each baseline trial the experimenter said, “Up goes the curtain,” and raised the curtain to reveal the two black screens already on the stage, 19cm apart. The experimenter made sure that infants were looking at the stage (tapping gently if they were not), then lifted both screens simultaneously to reveal either two objects (one behind each screen) or three objects (one behind one screen, two behind the other). Infants’ looking was measured from the moment the screens were completely out of view. The objects remained in place until infants looked away for two continuous seconds, or until infants looked for a total of 120 seconds, as indicated by the observer in an adjacent room who pressed a button to signal the experimenter at the end of each trial. When each trial ended, the experimenter said, “Down goes the curtain,” and lowered the curtain. Whether infants first saw the 2-Object or the 3-Object baseline trial was counterbalanced across infants. Also counterbalanced was whether the 3-Object baseline trials revealed two objects on the left or right side of the stage.

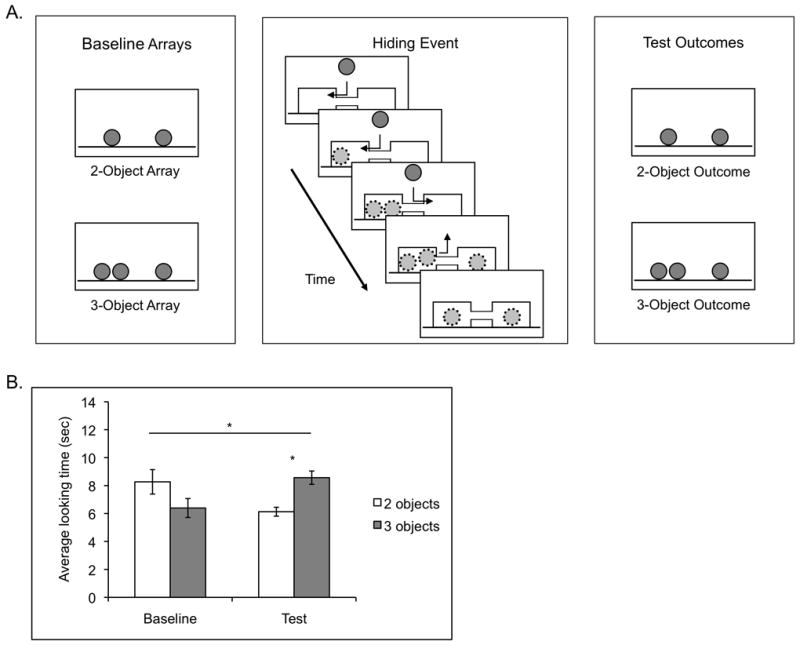

Figure 1.

A. Infants first saw one 2-object and one 3-object Baseline Array. On Test Trials, infants saw 3 balls hidden sequentially behind 2 screens. The screens were then lifted to reveal the unexpected 2-object outcome or the expected 3-object outcome. B. Infants’ looking to the Baseline and Test arrays. Bars depict standard error (*p<.05).

Test trials

On each of the eight test trials the experimenter said, “Up goes the curtain,” while raising the curtain to reveal an empty stage. The experimenter then lowered both screens simultaneously and placed them onstage 19cm apart, in the same positions they had occupied during the baseline trials. She lowered a ball midway between the two screens and, holding it approximately 12cm above the stage, squeaked it once, then hid it behind one of the screens. This procedure was repeated such that two balls were hidden in Array A (which always contained two objects) and one ball was hidden in Array B (which always contained one object). Whether the objects in Array A were hidden first or second was counterbalanced, as was the placement of Array A on the left or right side of the stage. Critically, the placement of the two balls in Array A always occurred in succession, such that infants never had to switch their gaze back and forth between Array A and Array B. When all three balls had been hidden behind the two screens, the experimenter lifted both screens simultaneously to begin the measurement period. On half of the test trials the screens were lifted to reveal the Expected Outcome (two balls behind one screen and one behind the other) and on the other half the screens were lifted to reveal the Unexpected Outcome (one ball behind each screen; Figure 1A). Expected and Unexpected Outcomes alternated across the eight test trials, with test trial order (Expected Outcome shown first or second) counterbalanced across infants. Each trial lasted until infants had looked away for two continuous seconds or had looked for a maximum of 120 seconds. Looking times more than 2.5 standard deviations from the mean were replaced by the same-trial average looking times of participants in the same test condition. (This was done across all of the 5 experiments reported here, resulting in the replacement of 2.8% of all trials.)

Across all experiments, inter-rater agreement on looking times between two trained observers unaware of experimental condition averaged 96.0%. (Across all 5 experiments the range was 95.3% to 96.4%.

1.2 Results

Baseline trials

To assess infants’ baseline preference to look at two vs. three objects, we first analyzed looking times from the baseline trials in a 2 (Array: 2 Objects vs. 3 Objects) × 2 (Trial Order: 2-Object array shown first or second) analysis of variance (ANOVA). We observed no effect of Array; infants looked equally to 2-Object (10.73 seconds) and 3-Object arrays (11.66 seconds), F(1, 16)=0.286, p=.600 (Figure 1B). No other effects were significant.

Test trials

We analyzed infants’ looking times from the eight test trials in a 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) × 4 (Pair: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th test pair) × 2 (Trial Order: Unexpected Outcome shown first or second) ANOVA. There was a significant effect of Outcome, F(1, 16)=21.996, p<.001, ηp2=.579. Averaged across test pairs, infants looked longer at the Unexpected 2-Object outcomes (mean 10.49 seconds) than the Expected 3-Object outcomes (mean 8.07 seconds, Figure 1B. There was also a marginally significant main effect of Pair, F(3, 48)=2.676, p=.058, ηp2=.143. Pair-wise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) showed infants looked longer on test pairs 1 (10.16 seconds), 2 (9.80 seconds) and 3 (9.66 seconds) than on pair 4 (7.49 seconds); no other pairs differed. In addition, there was a marginally significant Pair by Outcome interaction, F(3, 48)=2.678, p=.057, ηp2=.143. Infants had a stronger preference for the Unexpected 2-Object outcome in earlier than later test pairs.

Finally, we asked whether infants’ preference to look at two vs. three objects in test trials differed from their preference during baseline trials. A 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: 2 or 3 Objects) ANOVA revealed a marginally significant main effect of Trial Type, F(1,17)=3.652, p=.073, ηp2=.177, driven by infants looking slightly longer on baseline trials (11.19 seconds) than test trials (9.28 seconds). Critically, there was also a Trial Type × Outcome interaction, F(1, 17)=4.860, p=.042, ηp2=.222; infants looked longer at the 2-Object than the 3-Object outcome only in the test trials, when it was the unexpected result of an updating event in which three objects had been hidden (Figure 1B).

1.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 suggest that 11-month-olds can represent two arrays containing a total of three sequentially hidden objects. This finding extends the results of previous studies in which infants were shown to successfully remember a total of two sequentially hidden objects in a single array or in two arrays (Baillargeon, 1994; Káldy & Leslie, 2003, 2005; Koechlin et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1995; Uller et al., 1999; Wynn, 1992).

However, Experiment 1 and previous studies (Feigenson et al., 2002a; Uller et al., 1999) only required infants to update representations of arrays that were currently being attended that is, to perform updates to an array in succession before any other objects were introduced at another location. Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009) found 11-month-olds to have difficulty updating representations of hidden objects when seeing a sequence of crackers hidden in alternation between two locations. In Experiment 2 we sought to determine whether this updating difficulty would also obtain in a task involving non-food objects, in which no explicit ordinal choice was required, and in which infants were tested over multiple trials.

2. Experiment 2

Infants in Experiment 2 saw an event nearly identical to that of Experiment 1, in which three objects were sequentially hidden behind two screens. The total number of objects hidden and revealed, the number and placement of the hiding screens, the number of hand movements, and the presentation duration were identical to those in Experiment 1. The sole difference was that the hiding of objects alternated between the two screens rather than concluding at one location before moving on to the other.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

Eighteen full-term infants (8 boys) participated. Their mean age was 11 months, 16 days (range 11 months, 0 days to 11 months, 30 days). Six additional infants were excluded (3 for fussiness, 3 for experimenter error).

2.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those in Experiment 1.

2.1.3 Procedure

As in Experiment 1, infants saw two baseline trials: a 2-Object array and a 3-Object array (with side and order counterbalanced across infants). Infants then saw eight test trials, identical to those in Experiment 1 except that objects were hidden in alternation between the two screens. Infants first saw an object hidden behind the screen at Array A (two-object array), then a second object hidden behind the screen at Array B (one-object array), and finally, a third object hidden behind the screen at Array A (Figure 2A). The timing of each object placement was the same as in Experiment 1, and whether the presentation began on the left or right side of the stage was again counterbalanced across infants. An observer who was unaware of the design and hypotheses of the two experiments timed a subset of the test trial presentation events in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 (approximately 20% of all events) and found the overall presentation durations to be statistically equal.

Figure 2.

A. Infants first saw one 2-object and one 3-object Baseline Array. On Test Trials, infants saw 3 balls hidden in alternating order behind 2 screens. The screens were then lifted to reveal the unexpected 2-object outcome or the expected 3-object outcome. B. Infants’ looking to the Baseline and Test arrays. Bars depict standard error.

The test trial outcomes were identical to those of Experiment 1. Expected Outcomes always contained two objects behind one screen and one object behind the other, and Unexpected Outcomes always contained just one object behind each screen.

2.2 Results

Baseline trials

We first analyzed looking times from the two baseline trials in a 2 (Array: 2 Objects vs. 3 Objects) × 2 (Trial Order: 2-Object array shown first or second) ANOVA. Infants looked longer at the first baseline trial presented regardless of whether it was a 2-Object or 3-Object array, as revealed by a significant Array by Trial Order interaction, F(1, 16)=4.563, p=.048, ηp2=.222. There was no main effect of Array, F(1, 16)=1.609, p=.203. Infants did not look significantly differently at 2-Object (12.46 seconds) versus 3-Object (10.75 seconds) arrays.

Test trials

We next analyzed looking times from the eight test trials in a 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) × 4 (Pair) × 2 (Trial Order) ANOVA. Only a significant main effect of Pair appeared, F(3, 48)=3.002, p=.040, ηp2=.158. Pair-wise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) showed infants looked significantly longer on test pairs 1 (9.89 seconds) and 2 (9.56 seconds) than pair 4 (6.57 seconds); no other pairs differed. Critically, there was no main effect of Outcome, F(1, 16)=0.172, p=.684). Averaged across test pairs, infants looked equally at Unexpected 2-Object (8.51 seconds) and Expected 3-Object (8.20 seconds) outcomes.

As in Experiment 1, we asked whether infants’ preference to look at two vs. three objects differed between test and baseline trials. A 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: 2 or 3 Objects) ANOVA revealed only a significant main effect of Trial Type, resulting from infants looking longer overall during baseline than test trials, F(1, 17)=7.279, p=.015, ηp2=.300 (Figure 2B). Infants’ looking patterns did not change from baseline to test; Trial Type × Outcome interaction F(1, 17)=0.728, p=.405.

Finally, to examine the effect of the alternating object presentation, we compared looking times across Experiments 1 and 2. A 2 (Experiment: 1 vs. 2) × 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Trial Type, F(1, 34) = 10.866, p=.002, ηp2=.242. Regardless of which experiment infants were in, they looked longer during the Baseline trials (11.40 seconds) than the Test trials (8.82 seconds). We also observed a 3-way interaction between Experiment, Trial Type, and Outcome, F(1, 34) = 4.507, p=.041, ηp2=.117. Infants looked longer at the 2-Object arrays in the Test Trials, but not the Baseline trials, and only after seeing objects hidden in direct succession across two locations (Experiment 1), not when the objects were hidden in alternation across the two locations (Experiment 2).

2.3 Discussion

Experiment 2 required infants to track objects hidden in alternation across two locations. Despite the fact that number and type of objects, number of hiding locations, and presentation duration all were identical to those of Experiment 1, infants in Experiment 2 failed to update their representations of the arrays, looking equally at the expected and unexpected outcomes of the hiding event. Together, the results of Experiments 1 and 2 replicate those of Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009), this time using non-food items, using a less demanding paradigm in which no explicit choice was required, and using repeated trials. In both Feigenson and Yamaguchi’s cracker choice task and the violation-of-expectation looking-time task used here, 11-month-olds appeared to remember three total objects when objects were hidden in succession, but not when they were hidden in alternation.

This pattern suggests that infants may have difficulty updating memory representations that are no longer the focus of attention. Once they began attending to a new array, infants in Experiment 2 and in the studies by Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009) apparently were unable to return to a previously attended array and update its contents. This failure might reflect that infants’ memory representations are somewhat inflexible—that once infants have represented all of the objects in an array, they cannot easily alter that representation. Alternatively, the difference in results across our first two experiments might stem from the greater number of eye movements or attentional shifts required by Experiment 2.

To control for this possibility, we replicated Experiment 2 with one very simple change. We connected the two hiding screens demarcating Arrays A and B with a thin strip of foam-core, transforming them into a single dumbbell-shaped screen. At least two lines of work offer evidence that this type of linking causes adults to construe the scene as now containing a single connected object. First, in a Multiple Object Tracking (MOT) task where each target object was connected to a distractor object with a continuously distorting bar, adults exhibited great difficulty tracking just the targets. Their poor performance was due to an inability to keep attention from spreading along the surface linking the target and the distractor they automatically construed the target and the distractor as end-points of one continuous object (Scholl, Pylyshyn, & Feldman, 2001). Second, neuropsychological patients with Balint syndrome typically perceive only one of two unconnected circles, but can perceive both if the two circles are connected with a thin line (Behrmann & Tipper, 1994; Humphreys & Riddoch, 1993).

Based on these findings with adults, we hypothesized that connecting our two hiding screens into a single dumbbell-shaped screen would lead infants to construe the two screens as demarcating a single array. Therefore, even when the objects were hidden in alternation behind the left and right ends of the unified screen (in exactly the same order and spatial positions as in Experiment 2), infants might treat the presentation as involving three successive updates to a single array, rather than alternating updates to two arrays.

3. Experiment 3

The objects and presentation events in Experiment 3 were identical to those in Experiment 2, in which the objects were hidden in alternation between the two screens. The only change was that in Experiment 3 the two screens were connected by a thin strip of foam-core, creating a single dumbbell-shaped screen.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Eighteen full-term infants (12 boys) participated. Their mean age was 11 months, 17 days (range 11 months, 1 day to 11 months, 29 days). Five additional infants were excluded (3 for fussiness, 1 for experimenter error, 1 for parental interference).

3.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those from Experiments 1 and 2, with the exception of the screen. The 2 foam-core screens used in Experiments 1 and 2 were connected with a thin foam-core strip (19cm × 5cm) that attached the screens at their vertical midpoints (Figure 3A). The width of the new dumbbell screen (69cm) equaled the distance between the endpoints of the two screens in Experiments 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

A. Infants first saw one 2-object and one 3-object Baseline Array. On Test Trials, infants saw 3 balls hidden in alternating order behind the 2 ends of a dumbbell shaped screen. The screens were then lifted to reveal the unexpected 2-object outcome or the expected 3-object outcome. B. Infants’ looking to the Baseline and Test arrays. Bars depict standard error (*p<.05).

3.1.3 Procedure

Infants saw two baseline trials identical to those in Experiments 1 and 2. The only difference was that at the start of each baseline trial, the curtain was lifted to reveal the single dumbbell screen onstage. The experimenter then lifted the dumbbell screen to reveal the 2-Object array or the 3-Object array. As in Experiments 1 and 2, whether the 2-Object or the 3-Object baseline trial was presented first was counterbalanced across infants, as was the side of the stage on which the 2 objects appeared (on the 3-Object trial).

Test trials proceeded as in Experiment 2. The three objects were hidden in alternation, with the timing and spacing of object placement identical to those in Experiment 2. Each ball was lowered over the center part of the screen, stopping just before the foam-core connector obscured any part of the ball, and then was moved behind one of the ends of the dumbbell. After completing the hiding events, the experimenter lifted the dumbbell screen up and offstage in one straight motion. The test outcomes were identical to those in Experiments 1 and 2: Expected Outcomes contained two objects behind one side of the screen and one object behind the other, and Unexpected Outcomes always contained just one object behind each side of the screen.

3.2 Results

Baseline trials

We first analyzed the looking times from the two baseline trials in a 2 (Array: 2 Objects vs. 3 Objects) × 2 (Trial Order: 2-Object array shown first or second) ANOVA. Infants looked longer at the first baseline trial regardless of whether it was a 2-Object or 3-Object array, as revealed by a significant Array by Trial Order interaction, F(1, 16)=8.578, p=.010, ηp2=.349. There was no main effect of Array, F(1, 16)=0.009, p=.924; infants looked equally at 2-Object (9.38 seconds) and 3-Object (9.53 seconds) arrays.

Test trials

We next analyzed looking times from the eight test trials in a 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) × 4 (Pair) × 2 (Trial Order) ANOVA. A significant main effect of Outcome appeared, F(1, 16)=4.747, p=.045, ηp2=.229. Averaged across test pairs, infants looked significantly longer at the Unexpected 2-Object outcome (mean: 8.49 seconds) than the Expected 3-Object outcome (6.98 seconds) (Figure 3B). We also observed also a main effect of Pair, F(3, 48)=4.442, p=.008, ηp2=.217. Pair-wise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that infants looked significantly longer on test pair 1 (9.01 seconds) than on pairs 3 (7.07 seconds) and 4 (6.12 seconds), and on test pair 2 (8.74 seconds) than on pair 4; no other pairs differed.

We then asked whether infants’ preference to look at 2 vs. 3 objects in the baseline trials differed from their preference during the test trials. A 2 (Trial Type) × 2 (Outcome) ANOVA revealed no significant main effects or interactions; Trial Type × Outcome interaction F(1, 17)=0.951, p=.343.

Lastly, to examine the effect of the dumbbell-shaped screen on infants’ performance, we compared looking times across Experiments 2 and 3. A 2 (Experiment: 2 vs. 3) × 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Trial Type, F(1,34)=8.379, p=.007, ηp2=.198. Regardless of which experiment they were in, infants looked longer during the Baseline trials (10.53 seconds) than the Test trials (8.04 seconds). The 3-way interaction between Experiment, Trial Type, and Outcome was not significant, F(1, 34) = 1.674, p=.204.

3.3 Discussion

The results of Experiments 1-3 replicate the findings obtained by Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009). Infants in both paradigms successfully updated representations of hidden object arrays when updates could be performed to a given array in direct succession, but not when the updates alternated between two arrays. In addition, Experiment 3 shows that this was not due to any aspects of the timing of the presentation or to the eye movements required to track the objects. Because infants successfully represented the objects hidden in alternation between the two ends of a dumbbell-shaped screen, it appears that infants’ construal of a scene as containing either a single array (as in Experiment 3) or two arrays (as in Experiment 2) was critical in determining their success or failure.

However, we note that the success observed in Experiment 3 was not an overwhelming one. Although infants looked significantly longer at the unexpected 2-Object outcomes than the expected 3-Object outcomes during the test trials, neither the change in the direction of their preference from baseline to test, nor the change in their looking times from Experiment 2 to Experiment 3, reached statistical significance. For this reason, we wished to replicate the observed pattern of failure (at performing alternating updates to two spatially separated arrays) and success (at performing alternating updates to two ends of a single array).

In addition to our goal of replicating the pattern from Experiments 2 and 3, we also wished to ask whether the limitations on infants’ ability to update representations of hidden arrays constrain only the process of adding to an existing representation or whether they apply more broadly. In Experiments 1-3 and in the experiments by Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009), infants always saw events in which objects were added to hidden arrays. In our final two experiments we asked whether infants also would show limitations when updating representations via subtraction. Experiment 4 examined infants’ ability to update representations of hidden arrays when alternating updates between two spatially separated screens, and Experiment 5 examined infants’ ability to update a representation of the identical event sequence, but with the two screens connected into a single dumbbell. In addition, Experiments 4 and 5 extends our inquiry into the limits on infants’ updating abilities by probing a different type of updating. Testing subtraction updates might plausibly produce a different pattern of results than that observed with addition updates. It has been argued that subtraction events may be easier for infants to represent than addition events, since the number of items held in memory at the end of the computation is often smaller, and thus comparing the remembered items to what is revealed on the stage is easier (Uller et al., 1999). If mentally subtracting items is easier than mentally adding items, and if infants again show updating limitations when subtracting items, this would serve as a more powerful demonstration of infants’ updating constraints 1. Finally, an additional benefit of Experiments 4 and 5 is that, because they involved subtraction rather than addition, the absolute number of objects in the expected vs. unexpected outcomes was reversed relative to that in Experiments 1-3. This provides an additional test of our hypothesis.

4. Experiment 4

Previous studies show that infants can update working memory representations to reflect subtraction events. Five-month-olds who saw an array of two objects that was covered with a screen, and then saw one object removed, looked longer at the unexpected 2-object outcome than the expected 1-object outcome (Feigenson et al., 2002b; Koechlin et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1995; Wynn, 1992). And when shown an array of three objects that was covered, followed by the removal of one object, 5-month-old infants looked longer at the unexpected 3-object outcome than the expected 2-object outcome (Wynn, 1995). Notably, these previous demonstrations all involved watching events in a single hiding location.

In Experiment 4 we asked whether infants also can subtract objects from a representation of a hidden array when required to update arrays in alternation. We used a design parallel to that of Experiment 2. Infants first saw two objects hidden in direct succession in Array A, then saw one object hidden in Array B. Lastly, infants saw an object removed from Array A — an event that required returning to a previously stored representation and updating it. We predicted that infants would have difficulty revising the contents of a previously formed memory representation, and therefore that they would look equally at the unexpected outcome of three objects and at the expected outcome of two objects.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

Eighteen full-term infants (9 boys) participated. Their mean age was 11 months, 13 days (range 11 months, 1 day to 11 months, 28 days). Five additional infants were excluded (1 for fussiness, 2 for experimenter error, and 2 for parent interference).

4.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those in Experiments 1 and 2.

4.1.3 Procedure

Infants first saw two baseline trials identical to those in Experiments 1 and 2, containing one 2-object array and one 3-object array (with side and order counterbalanced across infants).

Each of the eight test trials began as in Experiment 1. After the two screens had been lowered, the experimenter lowered a ball midway between the screens and hid it behind the screen at Array A, then immediately lowered a second ball between the screens and also hid it behind the screen at Array A. The experimenter then lowered a third ball and hid it behind the screen at Array B. Next, the experimenter lowered her hand between the two screens and wiggled her fingers to show infants that her hand was empty. She reached behind the screen at Array A and removed one of the two balls that had been hidden there. The ball was removed from the stage tracing the same path as in its initial placement (Figure 4A). The experimenter then lifted both screens simultaneously to reveal the Expected 2-Object Outcome (one ball behind Screen A and one behind Screen B) or the Unexpected 3-Object Outcome (two balls behind Screen A and one behind Screen B), on alternating trials. Which side of the stage Array A appeared on was counterbalanced across infants.

Figure 4.

A. Infants first saw one 2-object and one 3-object Baseline Array. On Test Trials, infants saw 2 balls hidden behind one screen, 1 ball hidden behind the other screen, then 1 ball taken away from behind the first screen. The screens were then lifted to reveal the expected 2-object outcome or the unexpected 3-object outcome. B. Infants’ looking to the Baseline and Test arrays. Bars depict standard error.

4.2 Results

Baseline trials

We first analyzed looking times from the two baseline trials in a 2 (Array: 2 Objects vs. 3 Objects) × 2 (Trial Order: 2-Object array shown first or second) ANOVA. Infants who saw the 3-Object array first looked longer at the 3-Object array, but infants who saw the 2-Object array first looked equally at both arrays, as revealed by a significant Array by Trial Order interaction, F(1, 16)=5.481, p=.032, ηp2=.255. There was no significant effect of Array; overall, infants looked equally to 2-Object (8.92 seconds) and 3-Object (10.89 seconds) arrays, F(1, 16)=1.950, p=.182.

Test trials

We next analyzed looking times from the eight test trials in a 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) × 4 (Pair) × 2 (Trial Order) ANOVA. It revealed a significant effect of Pair, F(3, 48)=5.714, p=.002, ηp2=.263. Pair-wise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that infants looked significantly longer on test pairs 1 (9.60 seconds), 2 (9.87 seconds), and 3 (8.04 seconds) than on pair 4 (5.84 seconds); no other pairs differed. We also observed a marginally significant Outcome by Trial Order by Pair interaction, F(3, 48)=2.542, p=.067, ηp2=.137. However, no main effect of Outcome was observed, F(1, 16)=1.188, p=.292. Averaged across test pairs, infants looked equally at the Expected 2-Object (8.02 seconds) and the Unexpected 3-Object (8.68 seconds) outcomes.

We then asked whether infants’ preference to look at two vs. three objects differed between the baseline and test trials. A 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: 2 vs. 3 Objects) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Trial Type (F(1, 17)=4.541, p=.048, η2p=.211), with infants looking longer overall during baseline trials (9.91 seconds) than test trials (8.35 seconds). There was no Trial Type × Outcome interaction (F(1,17)=0.733, p=.404); infants’ looking patterns did not change from baseline to test (Figure 4B).

4.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 4 conceptually replicate those of Experiment 2 and also extend them to a subtraction event. Infants again appeared unable to represent the outcome of a sequence of updates alternating between two hidden object arrays.

As with Experiment 3, we next asked whether unifying the two hidden arrays behind a single dumbbell-shaped screen would improve infants’ performance, despite the presentation involving the same number and timing of events and requiring the same eye movements as Experiment 4.

5. Experiment 5

As in Experiment 4, infants saw two objects sequentially hidden in Array A (now either the right or left hand side of the dumbbell shaped occluding screen), then saw one object hidden in Array B (the other side of the dumbbell screen). Lastly, they saw an object removed from Array A.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

Eighteen additional full-term infants (9 boys) participated. Their mean age was 11 months, 9 days (range 11 months, 1 day to 11 months, 18 days). Three additional infants were excluded (1 for fussiness, 2 for experimenter error).

5.1.2 Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli, including the dumbbell-shaped screen, were identical to those used in Experiment 3.

5.1.3 Procedure

The baseline and test trials were exactly as in Experiment 4, except that the screens demarcating Array A and Array B were replaced with the single dumbbell screen used in Experiment 3 (Figure 5A). Each ball was lowered over the center of the dumbbell screen until just before the connector occluded the ball and then was moved behind the left or right side of the screen. The reverse path was used when the ball was subtracted from the array. As in Experiment 4, the Unexpected Outcome contained three objects and the Expected Outcome contained two.

Figure 5.

A. Infants first saw one 2-object and one 3-object Baseline trial. On Test Trials, infants saw 3 balls hidden behind a dumbbell shaped screen. The screen was then lifted to reveal the expected 3-object outcome or the unexpected 2-object outcome. B. Infants’ looking to the Baseline and Test arrays. Bars depict standard error (*p<.05).

5.2 Results

Baseline trials

We first analyzed the looking times from the two baseline trials in a 2 (Array: 2 Objects vs. 3 Objects) × 2 (Trial Order: 2-Object array shown first or second) ANOVA. There were no significant main effects or interactions. Infants did not look significantly differently at the 2-Object (8.27 seconds) and 3-Object (6.39 seconds) arrays, F(1, 16)=2.915, p=.107.

Test trials

We next analyzed looking times from the eight test trials in a 2 (Outcome: Expected vs. Unexpected) × 4 (Pair) × 2 (Trial Order) ANOVA. It revealed a significant main effect of Outcome, F(1, 16)=18.708, p<.001, ηp2=.539. Averaged across test pairs, infants looked longer at Unexpected 3-Object outcomes (8.57 seconds) than at Expected 2-Object outcomes (6.13 seconds). We also observed a significant main effect of Pair, F(3, 48)=3.480, p=.023, ηp2=.179. Pair-wise comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that infants looked significantly longer on test pairs 1 (7.32 seconds), 2 (7.68 seconds), and 3 (8.59 seconds) than on pair 4 (5.81 seconds); no other pairs differed. There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

We next asked whether infants’ preference to look at 2 vs. 3 objects in the baseline trials differed from their preference during the test trials. A 2 (Trial Type: Baseline vs. Test Trials) × 2 (Outcome: 2 vs. 3 Objects) ANOVA revealed a significant interaction, F(1, 17)=14.626, p<.001, ηp2=.462. Infants looked significantly longer at the 3-Object than the 2-Object outcome only in the test trials, when it was the unexpected result of a subtraction event (Figure 5B).

Finally, to determine whether infants’ looking time preferences were influenced by the need to revisit an already existing representation, we compared looking times in Experiments 4 and 5. A 2 (Experiment) × 2 (Trial Type) × 2 (Outcome) revealed a main effect of Experiment, F(1, 34) = 4.766, p=.036, ηp2=.123. Averaged across all trials, infants in Experiment 4 looked longer (9.13 seconds) than those in Experiment 5 (7.34 seconds). In addition, there was a significant Experiment × Trial Type × Outcome interaction, F(1, 34) = 8.713, p=.006, ηp2=.204. Infants’ preference to look at the 3-Object outcome only emerged when it was the result of a subtraction event that did not require them to update to multiple hidden arrays in alternation.

5.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 5 suggest that infants can successfully represent a subtraction performed on a hidden array, as long as they are not required to alternate updates across two separate hiding locations. In Experiment 5, the thin piece of foam-core connecting the two screens apparently led infants to succeed at representing the correct number of hidden objects, despite the fact that infants had to perform four distinct updating operations: first updating their representations of three objects as they were hidden sequentially behind the screens and then finally performing a subtraction from one of the arrays.

6. General Discussion

Previous studies demonstrate that infants can represent arrays of hidden objects in memory and can update these representations to accurately reflect changes to the array (Baillargeon, 1994, 2008; Cheries et al., 2008; Feigenson et al., 2002a, 2002b; Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009; Káldy & Leslie, 2003, 2005; Koechlin et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1995; Uller et al., 1999; Wynn, 1992, 1995). In these cases, updating is regarded as the process of altering an existing memory representation to reflect changes made outside of immediate perceptual experience. Despite this well-demonstrated ability, the present series of experiments suggests that infants face a striking limitation when updating object representations.

Experiment 1 confirmed that infants can update a representation of a hidden object array when the updates occur in direct succession. However, Experiment 2 showed that when they had to alternate between the arrays, (updating a representation of one array after representing objects elsewhere in the scene), infants failed. Experiment 3 showed that this failure was not due to low-level demands of eye movements or attention. When the two hiding locations were connected into a single dumbbell-shaped location, infants succeeded with the alternating presentation. Experiments 4 and 5 extended this pattern of results to a different type of object updating. Experiment 4 demonstrated that after watching a subtraction event involving an alternating presentation, infants failed to update a remembered array, whereas Experiment 5 showed that this failure was eliminated when the two arrays were connected into a single dumbbell-shaped location.

These experiments make several contributions toward better understanding infants’ object representations. First, our findings expand on the updating failures observed in earlier work (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009), demonstrating that infants’ difficulty in updating is not limited to memory for food items whose extent can be summed (Feigenson & Yamaguchi, 2009), to the need to make an ordinal choice between quantities, or to having just a single trial in which to perform the update. Instead, infants in the present experiments experienced similar failures with non-food objects, in a passive looking-time task and when tested over multiple trials. Second, our results show that updating is challenging for infants whether it involves mentally adding objects to or subtracting objects from a remembered array. Third, our findings suggest that spatial factors influence infants’ construal of the number of arrays in a scene. This, in turn, appears to determine whether infants are successful at updating object representations that require revisiting previously represented locations.

Our findings also raise questions for future work. One important direction for future inquiry is to examine the specific contents of infants’ updated representations. We note that while the present studies offer evidence that 11-month-old infants can update object representations when updates are non-alternating, our findings do not provide definitive evidence of the exact number of objects infants remembered under these circumstances. Because the unexpected outcomes in our experiments always involved an object disappearing or reappearing from the array that had been updated, we know that infants presented with non-alternating updates remembered the objects in an updated array (Array A). Future work should confirm that infants also represented the contents of the non-updated array (i.e., remember the one object in Array B). In addition, more work is needed to characterize infants’ representations in the conditions in which they failed. Experiments 2 and 4 showed that infants were unable to differentiate expected from unexpected outcomes when presented with alternating updates. These failures could reflect a complete loss of all representations currently being held (i.e., infants no longer representing any objects at either Array A or Array B). Alternatively, infants might have lost all representations only in the array they had attempted to update (i.e., infants represented no objects in Array A, but represented a single object in Array B). Or, infants might have lost only the representations in the updated array that occurred either before or after the attempted update (i.e., infants represented the first object that had been presented in Array A and the single object in Array B, or infants represented only the second object added to Array A and the single object in Array B). Although the present studies do not answer these questions, the pattern of performance observed by Feigenson and Yamaguchi (2009) supports this last possibility. Attempting to update a prior representation appeared to have resulted in infants’ losing the representation of the object that had been formed prior to the attempted update, effectively “wiping clean” infants’ representation of that array. Infants’ representation of the non-updated array appeared to be intact. However, further work should confirm this pattern under different testing conditions.

Interestingly, difficulty updating multiple memory representations in alternation also has been observed in adults. For example, adults are slower to update mental counts of shapes or numerals when switching back and forth between two running counts, as opposed to updating the same count in succession (Garavan, 1998; Gehring, Bryck, Jonides, Albin, & Badre, 2003; Kessler & Meiran, 2006; 2008; Oberauer, 2002). This reaction time cost when adults update in alternation has been interpreted as the time required to shift the internal focus of attention between items in working memory (Garavan, 1998; Gehring et al., 2003; Kessler & Meiran, 2006, 2008; Oberauer, 2002; Oberauer & Bialkova, 2009). Our results are consistent with such an account, although we note that adults are merely slower to perform alternating updates, whereas the infants we tested failed altogether to perform alternating updates. Given that the prefrontal cortex, which appears to be instrumental in controlling switches within working memory (D’Esposito, Detre, Alsop, Shin, Atlas, & Grossman, 1995; Kübler, Murphy, Kaufman, Stein, & Garavan, 2003; Rowe, Toni, Josephs, Frackowiak, & Passingham, 2000), develops relatively slowly compared to other brain areas, children may be more successful controlling and updating the contents of working memory as prefrontal cortex matures.

To summarize, in five experiments we confirmed and extended the finding of a striking limitation on infants’ ability to dynamically represent changing object arrays. Although previous studies reveal infants’ remarkable competence at remembering hidden objects and updating these representations over time, infants also face considerable challenges-- including the challenge of updating representations when updates do not occur in an orderly sequence. Crucially, infants’ construal of an event appears to influence their updating success.

Highlights.

Infants can represent hidden object arrays in memory and update these representations

We found that 11-mo. Olds can update 2 remembered arrays in direct succession

Infants failed to perform the same updates in alternating order

Infants successfully updated in alternation with 2 arrays connected by a thin bar

Construing a scene as containing 1 or 2 arrays modulates infants’ updating abilities

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Student Fellowship to M.M. (as M. Yamaguchi), and by a McDonnell Scholar Award and a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD054416 to L.F. The authors thank Justin Halberda for helpful discussion, Rachel Austin, Catherine Juravich Roe, Lenae Stansky, Andrea Stevenson, Arin Tuerk, and Allison Wessel for help with data collection, and as the families in the greater Baltimore area for their participation.

Footnotes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baillargeon R. Physical reasoning in young infants: Seeking explanations for unexpected events. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1994;12:9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon R. Innate ideas revisited: For a principle of persistence in infants’ physical reasoning. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(1):2–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon R, Spelke ES, Wasserman S. Object permanence in five-month-old infants. Cognition. 1985;20(3):191–208. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barner D, Thalwitz D, Wood J, Yang SJ, Carey S. On the relation between the acquisition of singular-plural morpho-syntax and the conceptual distinction between one and more than one. Developmental Science. 2007;10(3):365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M, Tipper S. Object-based visual attention: Evidence from unilateral neglect. In: Umilta C, Moscovitch M, editors. Attention and performance Conscious and nonconscious processing and cognitive functioning. Vol. 15. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. pp. 351–375. [Google Scholar]

- Bidell TR, Fischer K. Beyond the stage debate: Action, structure, and variability in Piagetian theory and research. Intellectual Development. 1992:100–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cheries EW, Mitroff SR, Wynn K, Scholl BJ. Cohesion as a constraint on object persistence in infancy. Developmental Science. 2008;11(3):427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Working memory capacity (Essays in cognitive psychology) New York: Psychology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito M, Detre JA, Alsop DC, Shin RK, Atlas S, Grossman M. The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature. 1995;378:279–281. doi: 10.1038/378279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson L, Carey S. Tracking individuals via object-files: Evidence from infants’ manual search. Developmental Science. 2003;6:568–584. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson L, Carey S. On the limits of infants’ quantification of small object arrays. Cognition. 2005;97:295–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson L, Carey S, Hauser M. The representations underlying infants’ choice of more: Object-files versus analog magnitudes. Psychological Science. 2002a;13:150–156. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson L, Carey S, Spelke ES. Infants’ discrimination of number versus continuous extent. Cognitive Psychology. 2002b;44:33–66. doi: 10.1006/cogp.2001.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenson L, Yamaguchi M. Limits on infants’ ability to dynamically update object representations. Infancy. 2009;14(2):244–262. doi: 10.1080/15250000802707096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K, Bidell T. Constraining nativist inferences about cognitive capacities. The Epigenesis of Mind: Essays on Biology and Cognition. 1991:199–235. [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H. Serial attention within working memory. Memory & Cognition. 1998;26(2):263–276. doi: 10.3758/bf03201138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Bryck RL, Jonides J, Albin RL, Badre D. The mind’s eye, looking inward? In search of executive control in internal attention shifting. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:572–585. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood BM, Santos L. The Origins of Object Knowledge. Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hood B, Willatts P. Reaching in the dark to an object’s remembered position: Evidence for object permanence in 5-month-old infants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1986;4(1):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys GW, Riddoch MJ. Interactions between object and space systems revealed through neuropsychology. In: Meyer DE, Kornblum S, editors. Attention and Performance XIV. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Huntley-Fenner G, Carey S, Solimando A. Objects are individuals but stuff doesn’t count: Perceived rigidity and cohesiveness influence infants’ representations of small groups of discrete entities. Cognition. 2002;85:203–221. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Lewis RL, Nee DE, Lustig CA, Berman MG, Moore KS. The mind and brain of short-term memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:193–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Káldy Z, Leslie AM. Identification of objects in 9-month-old infants: Integrating ‘what’ and ‘where’ information. Developmental Science. 2003;6:360–373. [Google Scholar]

- Káldy Z, Leslie AM. A memory span of one? Object identification in 6.5-month-old infants. Cognition. 2005;97(2):153–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Y, Meiran N. All updateable objects in working memory are updated whenever any of them is modified: Evidence from the memory updating paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:570–585. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Y, Meiran N. Two dissociable updating processes in working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34(6):1339–1348. doi: 10.1037/a0013078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibbe MM, Leslie AM. What do infants remember when they forget? Location and Identity in 6-month-olds’ memory for objects. Psychological Science. 2011;22(11):1500–1505. doi: 10.1177/0956797611420165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Dehaene S, Mehler J. Numerical transformations in five month-old human infants. Mathematical Cognition. 1997;3:89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler A, Murphy K, Kaufman J, Stein EA, Garavan H. Co-ordination within and between verbal and visuospatial working memory: Network modulation and anterior frontal recruitment. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1298–1308. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal D, Johnson MH. The “what” and “where” of object representations in infancy. Cognition. 2003;88(3):259–276. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElree B. Attended and non-attended states in working memory: Accessing categorized structures. Journal of Memory & Language. 1998;38:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- McElree B. Working memory and focal attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition. 2001;27:817–835. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher M, Tuerk AS, Feigenson L. Seven-month-old infants chunk items in memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112:361–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nee DN, Jonides J. Neural correlates of access to short-term memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;103(37):14228–14233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802081105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe N, Huttenlocher J, Learmonth A. Infants’ coding of location in continuous space. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22:483–510. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes LM, Ross-Sheehy S, Luck SJ. Rapid development of feature binding in visual short-term memory. Psychological Science. 2006;17(9):781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K. Access to information in working memory: Exploring the focus of attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28(3):411–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K. Selective attention to elements in working memory. Experimental Psychology. 2003;50(4):257–269. doi: 10.1026//1618-3169.50.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K, Bialkova S. Accessing information in working memory: Can the focus of attention grasp two elements at the same time? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2009;138(1):64–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Sheehy S, Oakes LM, Luck SJ. The development of visual short-term memory capacity in infants. Child Development. 2003;74(6):1807–1922. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JB, Toni I, Josephs O, Frackowiak RSJ, Passingham RE. The prefrontal cortex: Response selection or maintenance within working memory? Science. 2000;288:1656–1660. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl BJ. Object and attention: The state of the art. Cognition. 2001;80:1–46. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl BJ, Pylyshyn ZW, Feldman J. What is a visual object? Evidence from target merging in multi-element tracking. Cognition. 2001;80:159–177. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon T, Hespos SJ, Rochat P. Do infants understand simple arithmetic? A replication of Wynn (1992) Cognitive Development. 1995;10:253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Uller C, Carey S, Huntley-Fenner G, Klatt L. What representations might underlie infant numerical knowledge. Cognitive Development. 1999;14:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- vanMarle K. Infants use different mechanisms to make small and large number ordinal judgments. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2013;114(1):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler ME, Treisman AM. Binding in short-term visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2002;131:48–64. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.131.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn K. Addition and subtraction by human infants. Nature. 1992;358:749–750. doi: 10.1038/358749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn K. Origins of numerical knowledge. Mathematical Cognition. 1995;1:35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zosh JM, Feigenson L. Memory load affects object individuation in 18-month-old infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;113:322–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]