Abstract

Background

Informal care provided by family members is an essential feature of health care systems worldwide. Although caregiving often begins early in the disease process, over time informal caregivers must deal with chronic, debilitating, and life-threatening illnesses. Despite thousands of published studies on informal care, little is known about the intersection of informal caregiving and formal palliative care.

Objective

The goal of this review is to identify research priorities that would enhance our understanding of the relationship between informal caregiving and palliative care.

Design

To better understand palliative care in the context of caregiving, we provide an overview of the nature of a caregiving career from inception to care recipient placement and death and the associated tasks, challenges, and health effects at each stage of a caregiving career. This in turn leads to key unanswered questions designed to advance research in caregiving and palliative care.

Results

Little is known about the extent to which and how palliative care uniquely affects the caregiving experience. This suggests a need for more fine-grained prospective studies that attempt to clearly delineate the experience of caregivers during palliative and end-of-life phases, characterize the transitions into and out of these phases from both informal and formal caregiver perspectives, identify caregiver needs at each phase, and identify effects on key caregiver and patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Inasmuch as most caregivers must deal with chronic, debilitating, and often life-threatening conditions, it is essential that we advance a research agenda that addresses the interplay between informal care and formal palliative care.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is identifying research priorities at the intersection of informal caregiving and palliative care. We begin with a brief review of the prevalence of caregiving in the United States followed by characteristics of caregivers and care recipients, with the aim of identifying the subgroup of caregivers and care recipients involved in palliative care. To better understand palliative care in the context of caregiving, it is important to characterize the nature of a caregiving career from inception to care recipient placement and death and the associated tasks, challenges, and health effects at each stage of a caregiving career. This review provides a context for identifying key unanswered questions and recommendations designed to advance this area of research.

Prevalence of Caregiving

Providing care to an older family member is an activity that spans time, place, and culture. Family members are the backbone of health care systems worldwide.1,2 Broadly speaking, informal caregivers are family members, friends, or fictive kin who provide some form of care to an older adult with whom they have a relationship. Care may involve providing care coordination, hands-on assistance, and health-related services such as wound care, financial support, or monitoring on-site or long-distance to someone with a cognitive and/or physical impairment.3 They are involved in episodic, transitional, as well as long-term care and may need to assume responsibilities for care tasks for which they have little knowledge, training, or support.4–6

Currently there are no precise estimates of the number of family caregivers. Existing estimates vary widely based on how caregiving is defined, the sampling strategy used, and age and conditions of the person receiving care. At one extreme are prevalence estimates that 28.5% of the U.S. adult population (65.7 million) provided unpaid care to an adult relative in 2009, with the majority (83%) of this care delivered to people age 50 or older.7 At the other extreme, data from the National Long-Term Care Survey suggest that as few as 3.5 million informal caregivers provided instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) or activities of daily living (ADL) assistance to people age 65 and over.8 Intermediate estimates of 28.8 million caregivers (“persons aged 15 or over providing personal assistance for everyday needs of someone age 15 and older”) have also been reported.9

High-end estimates tend to be generated when broad and inclusive definitions of caregiving are used (e.g., “Unpaid care may include help with personal needs or household chores. It might be managing a person's finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly to see how they are doing.”)10 Low-end estimates tend to be generated when definitions require the provision of specific ADL or IADL assistance3,11,12 for comparison of estimates of prevalence rates.

Who Receives Care

Care recipients are typically women (66%) and older (80% are age 50 years or older), and their main presenting problems or illnesses are “old age” (12%), followed by Alzheimer's disease or other dementias (10%), cancer (7%), mental/emotional illness (7%), heart disease (5%), and stroke (5%). The average length of time caregivers report providing care is 4.6 years,7 but the length of time may be considerably more depending upon the condition of the individual receiving care. In the case of dementia, caregiving may range from 4 to 20 years.

Many of the conditions caregivers confront are chronic, debilitating, and life-threatening illnesses, and thus meet palliative care criteria, although caregiving often begins early in the disease process when the illness may not be imminently life threatening. Conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, cancer, heart disease, and stroke are common late life conditions and account for much of the caregiving provided to older individuals. Although many care recipients would be eligible for palliative care, little is known about whether or not such care is provided.

Caregiving Trajectory

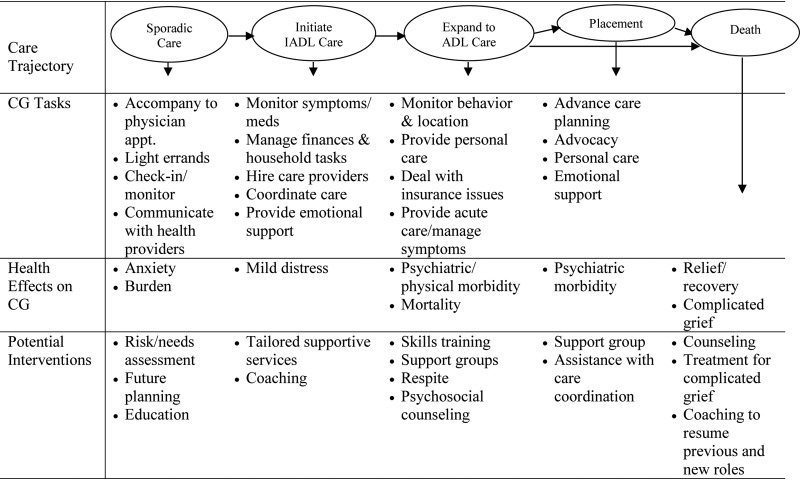

Figure 1 illustrates a common care trajectory for an older individual with cognitive or physical limitations who is living at home. Although caregiving may begin suddenly with the onset of a specific health condition such as stroke or cancer diagnosis, among older individuals it typically begins gradually with the emergence of IADL difficulties. Initial forays into a caregiving career involve providing sporadic support by being present at routine encounters with physicians or other health care providers,6,13 serving as proxy decision makers to severely ill older adults,14 or providing transient assistance to post-acute patients discharged from hospital to home.15

FIG. 1.

Care task demands, health effects and interventions, along care trajectory. Entries based on research evidence. ADL, activites of daily living such as bathing, dressing, toileting; CG, caregiver; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living such as cooking, cleaning, shopping.

Caregiving demands and the amount of time required to provide care increases as an individual no longer is able to perform IADLs (see Figure 1). Surveys suggest that caregivers provide assistance with a wide range of IADL tasks, including helping with transportation (83%), housework (75%), grocery shopping (75%), and preparing meals (65%).7 As the health condition of the care recipient worsens and disabilities increase, caregiver tasks expand to include more hands-on physical assistance with ADL tasks such as dressing, bathing, ambulating, and toileting (see Figure 1). Fifty-six percent of all caregivers provide ADL assistance such as helping the care recipient get in/out of bed (40%), dress (32%), and/or bathe (26%). Caregivers may also be required to closely monitor the activity of the person receiving care to assure their safety at home.7

The roles and responsibilities of caregivers tend to expand incrementally, with care tasks being cumulative over time (Figure 1). Increasing care demands often result in caregivers needing to leave the workforce, relocating to the care recipient's home, or having the individual receiving care move into the caregiver's home.

Throughout a caregiving career, caregivers play a critical role in communicating and negotiating with others about care decisions; providing companionship and emotional support; interacting with physicians and other health care providers; coordinating care needs; driving, doing housework and home repairs; shopping; completing paperwork and managing finances; hiring nurses and aides; helping with personal care and hygiene; lifting, transferring, and maneuvering the care recipient; and assisting with complex medical and nursing-related tasks (e.g., infusion therapies, tube feedings, wound care, medication monitoring). Helping with pain and symptom control is often a key caregiver responsibility for conditions such as cancer. Additionally, caregivers make difficult decisions about service needs and determine how best to access all of the services that may be needed, including the hiring and oversight of paid care providers. Few caregivers receive adequate instruction in these forms of care or are assessed for their ability or willingness to participate in such tasks.16

Caregiving does not terminate with nursing home placement (see Figure 1). Families continue to provide on-site monitoring and hands-on assistance with daily activities, participate in decision making about care needs, communicate care decisions with other family members, and monitor adequacy and quality of care. Thus, caregiving can be time intensive and emotionally and physically demanding even with residential placement.17,18

Although not illustrated in Figure 1, palliative and end-of-life caregiving is a common feature of most caregiving experiences and typically occurs during the latter stages of patient functional decline when ADL needs are high.

Health Effects of Caregiving

Understanding the health effects of caregiving is important for identifying supportive strategies, developing health policies, and planning for the organization and delivery of services. Figure 1 highlights known health effects as they unfold along the care trajectory. As shown, the negative health effects of caregiving increase with the amount of time and type of caregiving tasks required. Psychiatric symptoms (anxiety and depression) initially emerge in the early stages of caregiving, with more intensive hands-on assistance leading to significant physical health effects. Negative health effects can continue with nursing home placement but appear to resolve following the death of the person receiving care and hence termination of care responsibilities.19

Palliative and end-of-life caregiving pose additional challenges associated with accepting patient diagnoses, patient deterioration, and suffering, which together may generate intense emotional responses such as fear and dread, anger and disillusionment, anxiety, grief, helplessness, and hopelessness.20 Physical health effects are also aggravated at this stage as the combination of the physical demands of caregiving and the associated emotional turmoil take their toll on physical well-being of the caregiver.

Although the literature tends to emphasize the negative physical and psychiatric effects of caregiving, there are also positive features of this experience. Caregivers report a sense of pride, enhanced self-esteem, and mastery associated with caregiving; these positive effects are particularly prominent when the caregiver feels that he or she is able to enhance the patient's quality of life through symptom management or providing emotional support. One interpretation of these findings is that these responses represent attempts to find meaning in a fundamentally negative experience and as such can be viewed as meaning-based coping strategies.20 Positive accounts are not necessarily positive outcomes.

Supporting Family Caregivers

Figure 1 outlines the needs and range of supportive services for caregivers throughout the care trajectory. A robust research literature documents that caregiver interventions at each stage along this trajectory can effectively improve caregiver well-being. Taken as a whole these studies show that services, including education, skills-training, problem-solving, environmental redesign, and social support, can reduce stress, burden, and depression, enhance efficacy and skills, reduce health care utilization, and delay nursing home placement (see Rosalynn Carter Institute website for evidence-based caregiver interventions).21 Randomized controlled trials suggest that multicomponent, supportive, and risk reduction approaches effectively enhance emotional and physical health, skills and self-efficacy, and sleep quality.22–25 In contrast, one recent randomized trial testing a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care found no significant positive effects for outcomes such as preparedness to care, self-efficacy, competence, and anxiety, suggesting that introducing caregiver interventions this late in the trajectory may have limited impact.26

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions for Research on Caregiving and Palliative Care

Although caregiving often begins early in the disease process, most caregivers progress to caring for relatives with chronic, debilitating, and ultimately life-threatening illnesses. Yet few studies make explicit distinctions between the needs of family caregivers during palliative, end-of-life, and nonpalliative chronic illness phases. We list below some of the key unanswered questions about caregiving during palliative care.

Many caregivers are involved in end-of-life caregiving, but little is known about the extent to which palliative or hospice care uniquely affects the caregiving experience.27 What are impacts on time use, finances, employment, physical health, social isolation, lifestyle changes, and disruptions during palliative and end-of-life caregiving? This suggests a need for more fine-grained prospective studies that attempt to clearly delineate these phases, characterize the transitions into and out of these phases from both informal and formal caregiver perspectives, identify caregiver needs at each phase, and identify effects on key caregiver outcomes.

A related question concerns the role caregivers do and should play in the transition from curative to comfort to end-of-life care. How do caregivers understand their role and responsibilities, and what are their expectations from formal health care providers? Caregivers play a central role in determining the health care utilization of the patient throughout the patient's illness. Under what circumstances do caregivers opt for ineffective cure-oriented treatment when palliative or end-of-life care may be more appropriate? What are the individual and contextual factors that affect these choices and what is the best way to facilitate appropriate choices for the caregiver?

Appropriate tools or strategies for assessing caregiver needs and preferences during palliative and end-of-life care phases are lacking.28 We know a great deal about the needs of caregivers in general, but little about the unique needs of caregivers during palliative and end-of-life care phases. For example, having a good relationship, rapport, trust, and communication with health care providers are likely to be more important during palliative and end-of-life phases. When caring for a patient with advanced illness and disability, caregivers may be reluctant or ambivalent about expressing their own needs, because they view the needs of the patient as paramount. This suggests that explicit methods are needed to solicit the needs of the caregiver.

How do specialized palliative care services affect caregiver outcomes while caregiving (e.g., satisfaction with health care services, perceived suffering of the patient) and after death of the patient? A small literature suggests that there are both short-term and long-term benefits to the caregiver when specialized palliative care services are used. In the short-term, caregivers report fewer unmet needs, and in the long-term they show better adjustment to bereavement.29

There is considerable variation in the caregiving experience as a function of the underlying patient disease (e.g., neurologic condition versus physical illness); location of the patient (e.g., home versus nursing home); and caregiver attributes including age, relationship to the patient, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. These same factors may differentially affect caregivers during palliative and end-of-life caregiving phases.

Technology is increasingly being used to support caregiving.30 Technologies such as computers, smartphones, and web-based clinical care tools can be used to improve symptom monitoring and provide remote expertise to caregivers and patients and thereby support family caregiving during palliative care.31,32 The application of these methods is still relatively unexplored but holds promise for the future of caregiving.

There is a growing literature showing a relationship between caregiving and bereavement. The most common finding across multiple studies is that pre-bereavement levels of mental distress such as depression and anxiety are predictive of post-bereavement adjustment.33 A related finding is that high levels of burden, feeling exhausted and overloaded, lack of support, and experiencing role strain is associated with negative post-bereavement outcomes. Increased burden may also in part explain the higher mortality rate observed among caregivers of terminal patients who do not use hospice services compared to those who do.34 Consistent with these findings, several recent studies show that interventions designed to treat pre-bereavement caregiver distress prepare the caregiver for the eventuality of death and may be particularly effective in reducing adverse post-bereavement outcomes.33,35,36 These findings suggest that palliative care services may reduce caregiver burden and prepare the caregiver for the death of the patient, and thus contribute to better post-bereavement outcomes.

Informal caregiving and palliative care are inextricably intertwined. After three decades of research on caregiving, we know a great deal about the needs of caregivers, the effects of caregiving on the caregiver, and supportive interventions for caregivers. However, we know relatively little about the unique experience of caregivers during palliative care. A strong research focus on this stage of a caregiving career will likely yield valuable benefits for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support are grants from NINR (NR009574; NR013450) and NIMH (MH0900333). This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [5P30AG028741].

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillman BC. Black KJ. Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons; Nov, 2005. Staying the course: Trends in family caregiving. Public Policy Institute Issue Paper #2005-17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz R. Tompkins CA. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences Press; 2010. Informal Caregivers in the United States: Prevalence, Characteristics, Ability to Provide Care. Human Factors in Home Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone R. Cafferata GL. Sangl J. Caregivers of the frail elderly: A national profile. Gerontologist. 1987;27(5):616–626. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine C. Halper D. Peist A. Gould DA. Bridging troubled waters: Family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolff JL. Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Alliance for Caregiving, American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Aging, Duke University. National Long-Term Care Survey. 2004. www.nltcs.aas.duke.edu/ www.nltcs.aas.duke.edu/

- 9.National Family Caregivers Association, Family Caregiver Alliance; PhD. Prevalence, hours and economic value of family caregiving, updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates. In: Arno Peter S., editor. Kensington, MD: National Family Caregivers Association; San Francisco, CA: Family Caregiver Alliance, 2006; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Alliance for Caregiving, American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving and American Association of Retired Persons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff JL. Kasper JD. Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. Gerontologist. 2006;46(3):344–356. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson MJ. Houser A. Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons; Jun, 2007. Valuing the invaluable: A new look at the economic value of family caregiving. Public Policy Institute Issue Brief #IB82:1-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff JL. Boyd CM. Gitlin LN. Bruce ML. Roter DL. Going it together: Persistence of older adults' accompaniment to physician visits by a family companion. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shalowitz D. Garrett-Mayer E. Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberg D. Lusenhop R. Gittell J. Kautz C. Coordination between formal providers and informal caregivers. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(2):140–149. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000267790.24933.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donelan K. Hill CA. Hoffman C. Scoles K. Feldman PH. Levine C, et al. Challenged to care: Informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Aff. 2002;21(4):222–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz R. Belle H. Czaja S. McGinnis K. Stevens A. Zhang S. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292(8):961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams SW. Zimmerman S. Williams CS. Family caregiver involvement for long-term care residents at the end-of-life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(5):595–604. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz R. Boerner K. Shear K. Zhang S. Gitlin LN. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: A prospective study of bereavement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funk L. Stajduhar KI. Toye C. Aoun S. Grande GE. Todd CJ. Part 2: Home-based family caregiving at the end-of-life: A comprehensives review of published qualitative research (1998–2008) J Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):594–607. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving: Caregiver Intervention Database. www.rosalynncarter.org/caregiver_intervention_database/ www.rosalynncarter.org/caregiver_intervention_database/

- 22.Sörensen S. Pinquart M. Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinquart M. Sörensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):577–595. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belle SH. Burgio L. Burns R. Coon D. Czaja SJ. Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northouse LL. Katapodi MC. Song L. Zhang L. Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson PL. Aranda S. Hayman-White K. A psycho-educational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stajduhar KI. Funk L. Toye C. Grande GE. Aoun S. Todd CJ. Part 1: Home-based family caregiving at the end-of-life: A comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008) J Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):573–593. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson PL. Trauer T. Graham S. Grande G. Ewing G. Payne S. Stajduhar KI. Thomas K. A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;24(7):656–668. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abernethy AP. Currow DC. Fazekas BS. Luszcz MA. Wheeler JL. Kuchibhatla M. Specialized palliative care services are associated with improved short- and long-term caregiver outcomes. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(6):585–597. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz R, editor. Quality of Life Technology Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stern A. Valaitis R. Weir R. Jadad AR. Use of home telehealth in palliative cancer care: A case study. J TelemedTelecare. 2012;18(5):297–300. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.111201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagen NA. Addington-Hall J. Sharpe M. Richardson A. Cleeland CS. The Birmingham international workshop on supportive, palliative, and end-of-life care research. Cancer. 2006;107(4):874–881. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz R. Boerner K. Hebert RS. Stroebe W. Caregiving and bereavement. In: Stroebe MS, editor; Hansson RO, editor; Schut H, editor; Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: 21st Century Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2008. pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christakis NA. Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: A matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):465–475. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haley WE. Bergman EJ. Roth DL. McVie T. Gaugler JE. Mittelman MS. Long-term effects of bereavement and caregiver intervention on dementia caregiver depressive symptoms. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):732–740. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boerner K. Schulz R. Caregiving, bereavement and complicated grief. Bereavement Care. 2009;28(3):10–13. doi: 10.1080/02682620903355382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]