Abstract

Cytogenetic heteromorphisms are described as variations at specific chromosomal regions with no impact on phenotype. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of these chromosomal polymorphisms involved in reproductive failure in the Romanian population.

One thousand eight hundred and nine infertile patients, who were referred to Life Memorial Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, between January 2008 and April 2011, were investigated in this retrospective study. The frequency of chromosomal polymorphic variations was calculated for these patients. The control group is represented by 1116 fetuses investigated by amniocentesis between January 2009 and April 2011.

In this study 122 (6.74%) infertile patients and 63 fetuses (5.65%) showed chromosomal polymorphic variations. The differences between the two groups was not statistically significant (p <0.242) but there was statistical significance for some specific chromosomal polymorphisms [inv(9),1qh+, 9qh+, fra(17)].

Some chromosomal polymorphic variations appear to be associated with reproductive failure. The statistically significantly higher incidence of heterochromatic variations found in infertile individuals emphasizes the need to assess their role in infertility and subfertility.

Keywords: Chromosomal abnormalities, Heterochromatic variations, Infertility, Inversion, Subfertility

INTRODUCTION

Infertility is a significant marital problem, affecting up to 15.0% of couples of reproductive age [1,2]. Infertility can be caused by defects in the development of the urogenital system or defects in function of the endocrine system, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, or by defects in gametogenesis, sexual function, fertilization or early embryonic development [3]. Secondary or acquired infertility, such as after tubal diseases, vasectomy or exposure to gonadotoxins may also occur [4].

Genetic pathology is an increasingly important part of general human pathology as the number of described genetic diseases and their frequency increases. Study of human chromosomes play a key role in diagnosis, prognosis, treatment and monitoring of chromosomal abnormalities. In order to provide genetical counseling for affected families, cytogenetic analysis is the crucial investigation.

Several studies have been published regarding chromosome analysis in couples with reproductive failure who are referred for IVF (in vitro fertilization) or other treatments [5]. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in people with infertility appears to be greater than the overall incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in the general population [6]. It is unclear whether chromosomal abnormalities are one of the main causes of infertility in the human population. Many researchers believe that there is an association between genetic abnormalities and infertility in both men and women [7,8]. Approximately 40.0% of infertility cases are due to male pathology, 40.0% to female pathology, and the remaining 20.0% is a combination of the two [8]. About 5.0% of infertile men have chromosomal abnormalities, most of which involve sex chromosomes.

Chromosomal abnormalities are a major cause of male and female infertility and can be defined as an alteration of function and structure of chromosomes [9]. Cytogenetic abnormalities, both acquired and inherited, are one of the most common genetic causes of miscarriages early in pregnancies [10]. Most chromosomal abnormalities may cause a genetic imbalance that causes various phenotypic abnormalities (delayed growth and development, multiple congenital anomalies, disorders of sexuality and reproduction, etc.) due to partial trisomy or monosomy of the regions involved. Cytogenetic studies have been reported to determine the contribution of chromosomal abnormalities in patients with reproductive failure [11].

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects of chromosomal polymorphic variations involved in reproductive failure. Polymorphism variations mainly refer to the variants in the chromosomal heterochromatin region. To be classified as variants, chromosomal polymorphisms needed to be at least twice the size of the corresponding region on the second homologous chromosome [2]. Polymorphic variants on non acrocentric chromosomes usually occur in the paracentric heterochromatin on the long arms of chromosomes 1, 9 and 16, the short-arm regions of the D and G group chromosomes, and the distal heterochromatin of the Y chromosome. Increased lengths of the heterochromatic regions on the long arms of these chromosomes are designated as 1qh+, 9qh+, 16qh+ and Yqh+. The heterochromatin can be reduced in these chromosomes, such as in the case of 1qh–, 9qh– and 16qh–. Increased lengths of the short-arm satellites of the acrocentric D and G group chromosomes (13, 14, 15, 21 and 22) are designated as 14ps+ and 13ps+, while increased lengths of the short arms themselves are designated as p+ (e.g., 15p+) [12]. Because the heterochromatic region consists of highly repeated sequences of satellite DNA that does not encode proteins, the chromosomal polymorphism variations are considered normal karyotypic variations [13]. However, many recent studies indicate that chromosomal polymorphisms may cause certain clinical effects, such as infertility and spontaneous miscarriage [12,14,15].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

During the period from January 2008 to April 2011, 1809 infertile patients (969 men and 840 women) were referred to the Department of Reproductive Medicine, Life Memorial Hospital, Bucharest, Romania. Informed consent was obtained from the patients and donors prior to collection of heparinized blood samples. These patients were investigated for the frequency of chromosomal polymorphic variations. All the patients were evaluated by a skilled medical specialist and tested for antiphospholipid antibodies and relevant hormones. Ultrasonography was performed to rule out other causes of infertility. All cases were Caucasians.

The control group, considered to be a sample of the fertile population, consisted of 1116 fetuses (originating from spontaneous pregnancies). This group was investigated by amniocentesis in the period between January 2009 and April 2011. None of the pregnancies was obtained by an assisted reproductive technique (ART) and the reasons for referral were standard indications for amniocentesis such as abnormal serum screening levels or advanced maternal age.

Amniotic fluid samples were cultured in Amniomax complete medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and peripheral blood samples in PBmax and Chromosome B medium (Gibco); G-banded chromosomes were analyzed after harvesting [16]. At least 15 metaphases were analyzed for each case and 10 metaphases were karyotyped using light microscopy. The banding resolution was 400–550 bands per haploid set (BPHS). The results of the two groups were then compared.

Heteromorphism variations were reported according to the recommendations of the International System for Chromosome Nomenclature 2009 [17,18].

Statistical Analyses. The results for the two groups were compared using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test and calculated on line at the GraphPad Software website (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1.cfm8).

RESULTS

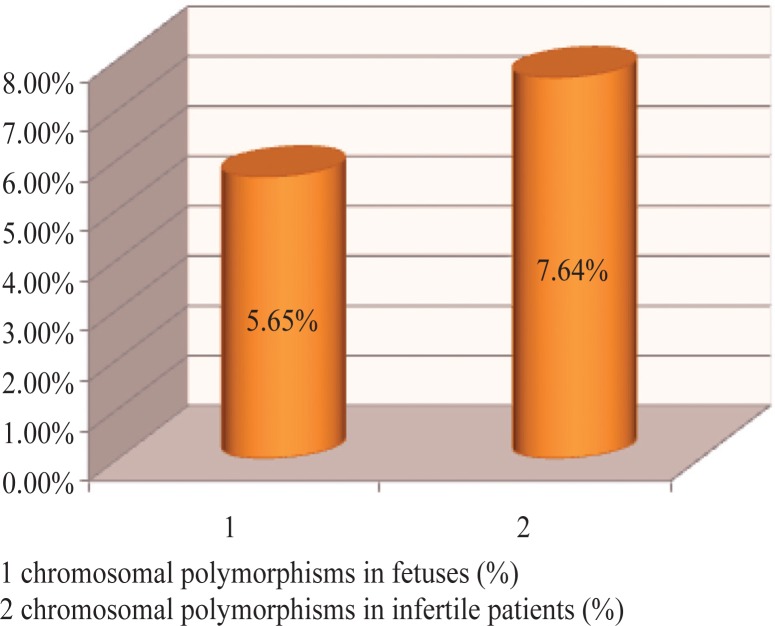

Cytogenetic analysis revealed a number of numerical and structural abnormalities, but in this study only chromosomal polymorphisms involved in infertility are reported (Table 1). Chromosomal polymorphism were found in 122/1809 (6.74%) infertile patients in the study group and 63/1116 (5.65%) fetuses in the control group; this was not statistically significant (p = 0.24) (Figure1). The difference between the patients and controls for some specific chromosomal polymorphisms is statistically significant [e.g., inv(9), 1qh+, 9qh+, fra(17)]. This shows that there was a noteworthy relation at risk of infertility and polymorphic variants. The frequencies, according to our study, of the chromosomal polymorphisms for patients and controls are shown in Table 2. The most common variant observed in infertile couples was inv(9) (2.27%). Other chromosomal variants with a high incidence were 1qh+ (1.22%) and 9qh+ (1.11%). The least common polymorphic variations in infertile couples were usually observed in the para-centric heterochromatin on the long arms of chromosomes 16, 16qh+ (0.28%), the short-arm of the D and G groups of chromosomes 15ps+ (0.22), 21ps+ (0.33), 22ps+ (0.44%), and the distal heterochromatin of the Y chromosome, Yqh+ (0.16%). The frequency of heteromorphisms in females was 2.76% and 3.98% in males. Twenty males who had heteromorphisms were oligozoospermic or azoosper-mic. The seven women with chromosome heteromorphisms had normospermic partners. As for the 1116 amniocentesis samples studied, we detected female karyotypes in 533 and male karyotypes in 583 fetuses. We observed polymorphisms in 63 fetuses (5.65%), 30 (1.65%) female and 33 (1.87%) male fetuses. The most frequent types of heteromorphisms in the control group were inv(9) at 3.76%, followed by 1qh+, 9qh+ and 16qh+ variants (0.36, 0.18 and 0.36%, respectively), followed by D and G group variants.

Table 1.

Numerical and structural abnormalities.

| Chromosomal Abnormalities | Karyotype | |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical abnormalities | Trisomy X Trisomy XXY Trisomy XYY Monosomy 45,X |

47,XXX 47,XXY 47,XYY 45,X |

| Structural abnormalities | Inversion | 46,XY,inv(1)(p12q23) 46,XX,inv(1)(p31q13) 46,XX,inv(3)p11q11.2) 46,XY,inv(3)(p11q11.2),inv(9)(p11q13) 46,XX,inv(5)(pterq13) 46,XX,inv(8)(p22q13) 46,XY,inv(10)(p11.2q21) |

| Translocation | 46,XY,t(1;4)(q43;q13) 46,XX,t(1;9)(q11;p13) 46,XX,t(1;19)(p13;p13.3) 46,XY,t(3;9)(q28;q32) 46,XX,t(3;13)(p21;p11.2) 46,XX,t(4;13)(p11;q11) 46,XX,t(9;22)(q34;q11) 46,XX,t(10;19)(q22;q13) 45,XY,t(13;14)(q10;q10) 45,XX,t(14;15)(q10;q10) |

|

Figure 1.

Comparison of the frequency of heterochromatic variations in the two studied groups. The distribution of the chromosomal polymorphisms in the two study groups (fetuses and infertile patients) is presented in this image.

Table 2.

Frequency of chromosomal polymorphisms in the studied groups.

| Chromosomal Polymorphic Variations | Control Group Frequency (%) | n | Study Group Frequency (%) | n | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion | inv(9)(p11q12) | 3.76 | 42 | 2.27 | 41 | 0.025 |

| Heteromorphisms qh+ | 1qh+ 9qh+ 16qh+ Yqh+ |

0.36 0.18 0.36 – |

4 2 4 – |

1.22 1.11 0.28 0.16 |

22 20 5 3 |

0.016 0.002 0.711 0.171 |

| Fragile sites | fra(17) fra(16) |

– – |

– – |

0.66 0.05 |

12 1 |

0.006 0.429 |

| Pseudo satellites | 14ps+ 15ps+ 21ps+ 22ps+ |

0.18 0.18 0.18 0.45 |

2 2 2 5 |

– 0.22 0.33 0.44 |

– 4 6 8 |

0.073 0.796 0.435 0.998 |

| Total | 5.65 | 63 | 6.74 | 122 |

DISCUSSION

Reproductive disorders are closely associated with chromosomal polymorphisms that were considered normal for a long period of time [19]. In recent years, more and more studies have shown an increased incidence of chromosomal polymorphism variation in infertile couples [20,21]. Some studies have demonstrated that 2.0–14.0% of infertile men have constitutional chromosomal abnormalities [20,21]. Chromosomal polymorphism between the two sexes in our study group showed some differences: 72 out of 969 men (7.43%) and 50 out of 840 women (5.95%). In both male and female groups, the inversion of chromosome 9 was more frequent. The most common types of chromosomal polymorphism in human infertility include inversion of chromosome 9. The frequency of inversions in the studied group was compared with rates in the population and estimated at 1.0–2.0% [22,23]. Involvement of chromosome 9 polymorphisms in reproductive failure has been reported previously [24]. There are multiple chromosome 9 heteromorphisms that cannot be detected by GTG-banding or C-banding [25].

In our study, inversion of chromosome 9 was found in 1.32% men and 0.95% women compared with literature data; 1.52% in men [26] and 0.66% in women [22]. Despite being categorized as a minor chromosomal rearrangement that does not correlate with abnormal phenotypes, many reports in the literature raised conflicting views regarding the association with sterility and subfertility [27,28].

In our study, morphological variations of constitutive heterochromatin were frequently detected during cyto-genetic analysis. Most often, chromosomes vary in size and position of heterochromatin in the 1qh, 9qh, and 16qh regions. Although inherited variants have been reported not to be associated with any risk for phenotypic abnormalities, chromosomal heteromorphisms have been found to have a higher frequency relative to the normal population and have been regarded as abnormalities in some studies [11,17,20,21]. Recent studies suggest that classical euchromatic variants of 9qh+/12qh+ and heteromorphism on chromosome 6q may be responsible for recurrent abortions [29,30]. However, in this study we found a statistical association between some chromosomal polymorphisms, namely, inv(9), 1qh+, 9qh+, fra(17) and infertility. In our study, the frequency of 1qh+ and 9qh+ was statistically significantly increased in women with primary infertility and in men with azoospermia which was confirmed by other studies [31,32]. Earlier studies had not investigated polymorphism and chromosomal aberrations as a determining factor in infertility in Romania, therefore, this study could important in this regard.

CONCLUSIONS

Chromosomal abnormalities and even heteromorphisms are significant etiological factors leading to fertility problems. The statistically significantly higher incidence of heterochromatic variations found in infertile individuals in this study emphasizes the need to evaluate their role in infertility and subfertility.

The overall high prevalence of chromosomal polymorphisms in infertile couples, compared to the normal population, needs to be confirmed with further investigations and larger study populations to delineate the role of “harmless” chromosomal aberrations in the etiology of infertility.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Kretser DM. Male infertility. Lancet. 1997;349(9054):787–790. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gersen SL, Keagle MB. The Principles of Clinical Cytogenetics. New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamel RM. Management of the infertile couple: an evidence-based protocol. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(1):8–21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah K, Sivapalan G, Gibbons N, Tempest H, Griffin DK. The genetic basis of infertility. Reproduction. 2003;126(1):13–25. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raziel A, Friedler S, Schachter M, Kasterstein E, Strassburger D, Ron-El R. Increased frequency of female partner chromosomal abnormalities in patients with high-order implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(3):515–519. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babu A, Agarwal AK, Verma S. A new approach in recognition of heterochromatic regions of human chromosomes by means of restriction endonucleases. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42(1):60–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speroff L. Women’s healthcare in the 21st century. Maturitas. 1999;32(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Han W, Guan C, Wang G, Zhu X, Jiang M, et al. Cytogenetic study on couples with a history of re-productive failure in China. J Reprod Contraception. 2009;20(4):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortés-Gutiérrez EI, Cerda-Flores RM, Dávila-Rodríguez MI, Hernández-Herrera R, Vargas-Villarreal J, Leal-Garza CH. Chromosomal abnormalities and polymorphisms in Mexican infertile men. Arch Androl. 2004;50(4):261–265. doi: 10.1080/01485010490448750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fritz MA, Speroff L, editors. Recurrent early pregnancy loss Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. pp. 1191–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madon PF, Anthalye AS, Parikh FR. Polymorphic variants on chromosomes probably play a significant role in infertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;11(6):726–732. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhasin MK. Human population cytogenetics: a review. Int J Hum Genet. 2005;5(2):83–152. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuce H, Tekedereli I, Elyas H. Cytogenetic results of recurrent spontaneous miscarriages in Turkey. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(6):CR286–CR289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin FI, Yilmaz Z, Yuregir OO, Bulakbasi T, Ozer O, Zeyneloglu HB. Chromosome heteromorphisms: an impact on infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25(5):191–195. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daya S. Issues in the etiology of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;6(2):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell ISCN 2009. An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. 2009.

- 17.Babu A, Verma RS. Characterization of human chromosomal constitutive heterochromatin. Can J Genet Cytol. 1986;28(5):631–644. doi: 10.1139/g86-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura Y, Kitamura M, Nishimura K, Koga M, Kondoh N, Takeyama M, et al. Chromosomal variants among 1790 infertile men. Int J Urol. 2001;8(2):49–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong Y, Zhou W, Tao J, Wang S, Zhao X., 1 Do polymorphic variants of chromosomes affect the outcome of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer treatment? Hum Reprod. 2011;26(4):933–940. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caglayan AO, Ozyazgan I, Demiryilmaz F, Ozgun MT. Are heterochromatin polymorphisms associated with recurrent miscarriage? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(4):774–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yakin K, Balaban B, Urman B. Is there a possible correlation between chromosomal variants and spermatogenesis? Int J Urol. 2005;12(11):984–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goud TM, Mohammed Al Harassi S, Khalfan Al Salmani K, Mohammed Al Busaidy SM, Rajab A. Cyto-genetic studies in couples with recurrent miscarriage in the Sultanate of Oman. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18(3):424–429. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khaled R, Gaber, Hala T, El-Bassyouni HT, El-Gerzawy A. Pericentric inversion of chromosome 1 and 9 in a case with recurrent miscarriage in Egypt. J Am Sci. 2010;6(8):154–156. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lissitsina J, Mikelsaar R, Punab M. Cytogenetic analyses in infertile men. 2006;52(2):91–95. doi: 10.1080/01485010500316030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun JS, Jang SK, Choi OH. Cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with reproductive dysfunction. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(5):760–768. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starke H, Seidel J, Hen W, Reichardt S, Volleth M, Stumm M, et al. Homologous sequences at human chromosome 9 bands p12 and q13-21.1 are involved in different patterns of pericentric rearrangements. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10(12):790–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davalos IP, Rivas F, Ramos AL, Galaviz C, Sandoval L, Rivera H. Inv (9) (p24q13) in three sterile brothers. Ann Genet. 2000;43(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3995(00)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teo SH, Tan M, Knight L, Yeo SH, Ng I. Peri-centric inversion 9-Incidence and clinical significance. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1995;24(2):302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dundar M, Caglayan AO, Saatci C, Batukan C, Basbug M, Ozkul Y. Can the classical euchromatic variants of 9q12/qh+ cause recurrent abortions? Genet Couns. 2008;19(3):281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caglayan AO, Ozgun MT, Demiryilmaz F, Ozyazgan I. Can heterochromatin polymorphism of chromosome 6 affect fertility? Genet Couns. 2009;20(2):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minocherhomji S, Athalye AS, Madon PF, Kulkarni D, Uttamchandani SA, Parikh FR. A case-control study identifying chromosomal polymorphic variations as forms of epigenetic alterations associated with the infertility phenotype. 2009;92(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eiben B, Leipoldt M, Rammelsberg O, Krause W, Engel W. High incidence of minor chromosomal variants in teratozoospermic males. Andrologia. 1987;19(6):684–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1987.tb01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]