Abstract

Background:

Animal bite is one of the problems of public health which has the potential risk of rabies disease. This study was conducted to determine the epidemiology of animal bite in Aq Qala city from 2000 to 2009.

Materials and Methods:

In this descriptive cross-sectional study, 13142 cases of animal bites which were recorded in Rabies Treatment Center of Aq Qala City were entered into the study by census method. The data were collected from the registered office profile of people who had referred to this center. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency distribution, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and Chi-square test.

Findings:

Of 13142 registered cases, 72.1% were men and 27.9% were women. The mean age of the victims was 25.0 ± 17.8 years, most of whom (84%) lived in villages. Also, most cases of animal bite were done by dogs, (97.8%) occurred in legs (69.6%). Most of the victims were students (28.9%). The highest frequency of bites happened in spring (28.8%). The incidence rate of animal bite was 1222/100,000 people. The highest and lowest incidence rates were 1608/100 000 in 2004 and 1117/100,000 in 2009, respectively. There was a significant relationship between season and the number of bites (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The incidence of animal bite in Aq Qala city was higher than that in other studies in different parts of the country. Considering the high cost of antirabies serum and vaccination, it is essential to take necessary measures reduce the incidence of this problem.

Keywords: Animal bite, Aq Qala, epidemiology, incidence, rabies

INTRODUCTION

Animal bites are serious threats to human health since their subsequent infection, such as rabies, is deadly.[1] The fatality rate of this disease is one hundred percent and, after the emergence of clinical symptoms in both humans and animals, this disease is not curable and the patient is condemned to death.[2] Rabies is a vaccine preventive diseasethat due to WHO reports kills 55,000 people every year, mostly children.[3]

In different parts of the world, over 10 million people annually receive antirabies treatment after animal bites in order to prevent from the disease.[4] Due to the lack of an advanced patient care system, the real number of the patients is probably more than what has been reported.[5] Dogs have the main role in the transmission of the disease to humans.[3,6] Besides the health importance in humans, the incidence of the disease in livestock leads to considerable economic losses.[7]

Rabies has long been reported in Iran.[8] From 1995 to 2004, on average, 8.4 people died annually because of this disease. In 2005, 118 517 animal bite cases were reported and its incidence was 173/100,000 people in 2003.[9] Rabies exists in Iranian wildlife and the livestock infection occurs frequently.[10,11] The increasing rate of curs, the expanding number of animal bites and the distribution of rabies in many provinces of the country is alarming, which calls for more attention to the control of the disease and research on its different aspects.[12]

The study by Dadipour et al. in Kalale City (northern part of the Iran) revealed the increased incidence rate of animal bite during 2004 to 2006 and the incidence rates in 2004, 2005, and 2006 were 787, 745, and 788, respectively, and the total incidence rate was 773 per 100,000 people.[1] In a study conducted in Thailand, 16.2% of animal bites were in children under 13 and 86% of them were dog bite. Most bites were in fall and school holiday seasons in adults and children, respectively.[13] In Iran, the rate of animal bite is the highest in Golestan Province in Iran; in 2008 and 2009, these rates were 610 cases and 593 cases per 100,000 people, respectively.[14] Aq Qala city in Golestan Province is a region with a high rate of animal bite.[13] This study was conducted to investigate the epidemiology of animal bites in this city between 2000 and 2009.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive cross-sectional study reviewed 13,142 cases of animal bites recorded from 1998 to 2009 in the Rabies Treatment Center of Aq Qala city, which were selected by census method. The data were collected through the information of the registered profiles of individuals who had referred to the Rabies Center of AqQala city. Normally, these forms included variables of age, gender, living place, type of biting animal, occupation, injury status (deep, superficial, direct, over clothes), bite site (hand, leg, body, face, and head or neck), bite date, the number of receiving antirabies vaccination and serum and tetanus vaccine. The obtained data were entered into the SPSS statistical software and were analyzed by descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentage, mean, and standard deviation and chi square test. To calculate the incidence rate, the population of Aq Qala city was obtained from Management and Planning Organization of the province and the calculations were conducted based on them. Reliability was considered 95%.

RESULTS

In this study, of 13 142 cases of animal bite, 9479 (72.1%) were men and 3663 (27.9%) were women. The studied population was from 1 to 91 years old with mean and standard deviation of 25.0 ± 17.8 years. The highest cases of bites were related to the age range of 11-15 years (2320 cases) (17.7%). The residential location of 11,038 cases (84%) was villages, and 2104 cases (16%) lived in cities. The most number of victims were bitten by dogs (12,895 cases) (98.8%). After dogs, came cows (1.6%), cats (0.3%), camels, horses, and donkeys (each with 0.1%).

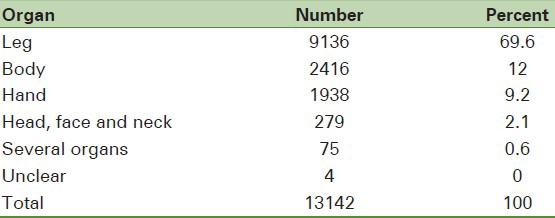

The frequency of bites in different seasons was as follows: Spring with 3792 cases (28.8%), winter with 3481 cases (26.5%), summer with 3189 (24.3%) and fall with 2680 cases (20.4%). According to the Chi-square test, there was a statistically significant relationship between the variables of number of bites and season (P < 0.05). The most common bitten part of the body was legs with 9136 cases (69.6%) [Table 1]. In this study, 6463 cases (72%) received full post-exposure vaccination. In 9348 (71.2) cases, biting was from over the clothes; in 2121 cases (38.1%), it was on the naked parts of the body; 1533 cases (11.7%) were superficial bites, and 43 cases (3%) were deep while the status of 97 cases (7%) was not clear.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of animal bites in Aq Qalq city from 2000 to 2009

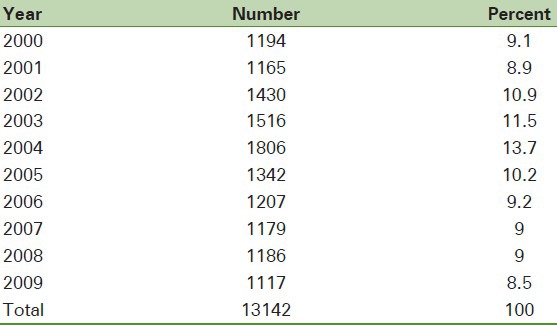

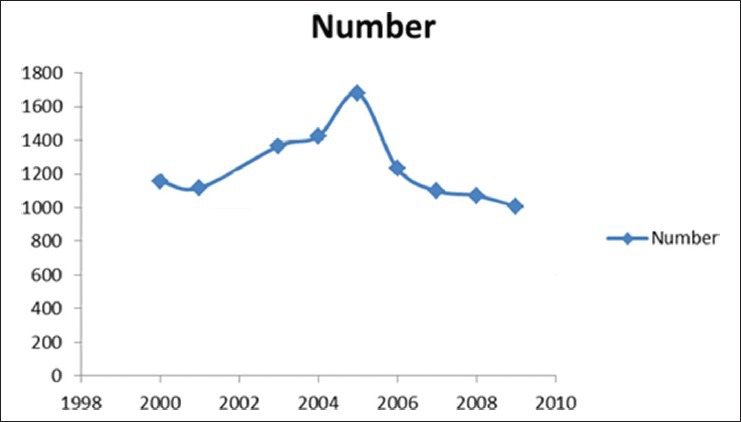

The highest and least numbers of bites were in 2004 and 2009, respectively [Table 2]. Also, the results showed that the highest incidence rate was in 2004 with 1806 cases per 100,000 people and its least rate was related to 2009 with 1117 cases per 100,000 people [Figure 1]. The average incidence rate during these 10 years was obtained as 1222 cases per 100,000.

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of animal bites in terms of years in Aq Qala city from the 2000 to 2008

Figure 1.

Trend of animal bite incidence rate during 2000-2009 in Aq Qala city, Iran

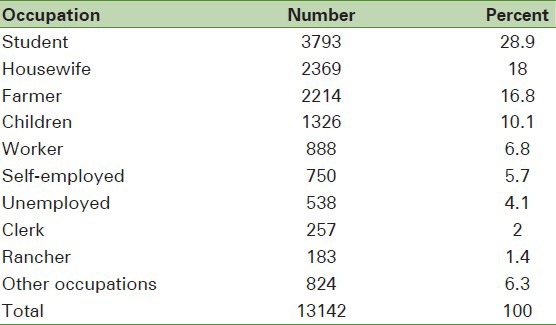

The rate of animal bites in this city had an ascending trend from 2001 to 2004 and descended until 2009 [Table 1]. Most of the victims were students with 3739 cases (28.9%), after them came housewives with 2369 cases (18%), farmers with 2214 cases (16.8%) and children under 6 with 1326 cases (10.1%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of animal bites in Aq Qala city during 1998-2009 in terms of occupations

DISCUSSION

Animal bites are considered one of the fundamental issues in public health of countries because of the risk of rabies and the costs of anti-rabies serum and vaccine for treatment and prevention and also due to livestock and economic losses caused by this disease. The results of the present study revealed that the incidence rate of animal bites in Aq Qala city during 2000-2009 with the mean of 1122 per 100,000 people fluctuated between 1117 and 1806 per 100,000 people, which is higher than the published figures and statistics of the country. According to the statistics of Health Center of Golestan Province, these rates were 610 and 593 per 100,000 people in 2006 and 2007 for the entire province, respectively.[14] Moreover, the statistics of Ministry of Health shows that the incidence rate of animal bites increased from 35.1 cases in 1986 to 151 cases in 2001 per 100,000 people; this increase can be attributed to (1) holding some educational programs for increasing public awareness in terms of the risks caused by animal bite and the importance of timely preventive treatment for the lack of incidence of rabies in humans and (2) decreasing the activities of the committee for elimination of curs.[2] In fact, in Aq Qala city, some other reasons can be mentioned for this increase, which were lack of domestic dog and sheepdog collaring and lack of fencing and physical bordering of the houses, specifically in villages of this city and even in the city itself. The findings showed that the vast majority of bites were dog bites. This rate was 246 cases per 100 000 people in the study performed by Amiri and Khosravi in Shahrood city.[15] Sheikholeslami et al. reported this rate as varying between 180 and 241 cases per 100,00,00 people in Rafsanjan city.[16] This rate was 100,000 people in the study by Dadipour et al. in Kalale during 2002-2004.[17] Also, it was 36.6 in Uganda and 773 in Fevre's investigation per 100,000 people.

The decrease in the incidence rate between 2005 and 2009 can be attributed to the increase in proper construction of buildings with physical boundaries under the Mehr Housing Plan in this city, especially in rural areas, and public education on the importance of dog collaring.

The mean and standard deviation of the age victims were 25.1 ± 17.8 years; they were equal to 27 ± 17.1 in the research by Sheikholeslami et al. in Rafsanjan, which is in agreement with the present study.[16] Also, 29.6% of the victims were under 13 years old; this was 18% in Sheikholeslami et al.[16] and 16.6% in Sriaroon et al. in Thailand, which is not in parallel with this study.[13] The studies also showed that 10.1% of the patients are the children under 7 years old which was due to their love for animals, their inexperience and carelessness in contact with animals and their inability to run away or confront with these animals.

Seventy two point one percent of animal bites were among men (with the gender ratio of 2.58). This ratio was between 52% and 85% in other studies[1,15,17,18,19] which is in relative agreement with most of the undertaken studies. This can be the result of more mobility of males in society, especially in traditional and developing countries.

Most of the victims (84%) lived in villages, which is in relative agreement with other studies.[15,16,20] Of course, the ratio of village residence in the studied communities can be involved in these differences. According to the statistics in 2005, about 70% of the population of Aq Qala city was rural; in other words, the rural to urban people ratio was 2.3. If this were considered as the basis of rural ratio, the animal bite ratio of 3.2 would be obtained during the considered ten years, indicating that rural people are more susceptible to this problem. This is an expected fact.

The vast majority of biting species (97.8%) was dogs, followed by cows (1.6%). In most of the studies performed inside and outside the country, dogs ranked first. This indicates the importance of collaring and vaccinating domestic and sheep dogs and the necessity of eliminating curs. Considering the 70% of rural population in this city, the reason for the high rate of biting by dogs in the present study can be attributed to the presence of dogs in most houses, many of which do not have collars and freely wander in houses, alleys and streets. In most studies, cats come after dogs, which is not in agreement with the present study. Here, cats were responsible for only 0.3% of bites.

Considering anatomic location of the bites, the majority of cases were related to legs (69.6%), which was 67% in Dadipour et al.[1] Bahonar et al. obtained 69.7%,[20] which is not in agreement with this study. However, this was equal to 34% in Sheikholeslami et al.,[16] 35.6% in Hobubati et al.[21] and 40.2% in Fevre et al.,[17] which are not in agreement with the present study. In previous studies, hand was the most common bitten part of the body after leg while in this study, body was bitten more than hand; this difference was due the difference in the anatomic categorization in these studies.

In terms of occupation, students had 28.9% of the cases; in other studies also, this group had the highest frequency. In Bahonar et al.'s study, students constituted the highest frequency with 34.4%.[20] This rate was equal to 20.9% in Amiri and Khosravi[15] and 27.4 in Hobubati,[21] which are in correspondence with the present research. The reason of high frequency of animal bite in students can be due to their stimulating animals because of their age. Sriaroon et al. concluded in their studies that there are two waves of increase in animal bite which are consistent with the school holiday season as a result of playfulness of this age group and their stimulation of animals, especially dogs.[13] Considering the fact that most cases of animal bites occur among teenagers and students, specific attention to them in terms of increasing their awareness about rabies, preventing them from getting close to curs and stimulation them and applying protective tips while being in contact with curs can have important roles in decreasing cases of animal bites.[2]

In terms of seasons, the highest rate of biting occurred in spring, winter, summer and fall, respectively, which is in line with the findings of Dadipour et al.[1] In the study of Bahonar et al., the highest cases of biting occurred in winter and spring, respectively, which is a bit different from this study.[20] Researchers have attributed the high rate of biting in spring and winter to the increased rate of traffic in rural and agricultural areas[1] and to the increased activity of animals seeking foods,[6,7] respectively.

Vaccination against rabies was incomplete (three times and less) in 72% of the cases; of course, the survival of the biting animal up to 10 days after the attack was a criterion for completing vaccination. This finding was not in agreement with the findings of Dadipour et al.[1] and Amiri and Khosravi in Shahrood[15] which obtained 90.1% and 100%, respectively. Considering the 100% fatality rate of rabies, performing full vaccination after biting is the best way for prevention.

One of the limitations of this study was its descriptive method. Also, a change happened in the data collection manner in early 2008 in which a small number of variables were changed and added; consequently, the investigation of their trends and obtaining the results became difficult in this study. Lack of awareness from the risks caused by animal bites had caused some patients no to refer to the anti-rabies treatment centers; thus, their information was not recorded in the data and not considered in the final interpretation of the results. Also, it was not possible for this study to access the information about the measures taken before going to the rabies center, reference type (with delay or without delay) and the status of the biting animal after 10 days.

CONCLUSION

The incidence of animal bite in Aq Qala city was higher than that of other parts of the country, as revealed by other studies. Considering the high costs of anti-rabies vaccination and serums, it is essential to take the required measures to decrease this problem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to Thank Mr. Salehnia and Mr. Shirmuhammadli (the staff of the Rabies Preventive Treatment Center, Aq Qala city) who assisted us in this study. Mean while we are very grate full for Golestan University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dadipour M, Salahi R, Ghezelsofla F. Animal bite epidemiology of stigma in the city during 2003-2005. J Gorgan Uni Med Sci. 2009;11:76–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.1st ed. Tehran: Pasteur Institute of Iran and Center for Disease Management; 2003. National Guid lines for Rabies Control; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World organization for Animal Health. Rabies: A priority for human and animal, Bulletin. 2011;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Eastern Mediterranean Region Annual ports of Regional Director (1950-2000), Alexandria World Health Organization Regional office for Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. WHO. Strategies for the control and elimination of rabies in Asia, Report of a WHO Interregional Consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfukenyi DM, Pawandiwa D, Makaya PV, Ushewokunze-Obatolu U. A retrospective study of rabies in humans in Zimbabwe, between 1992 and 2003. Acta Trop. 2007;102:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahonar AR, Rashidi H, Simani S, Fayaz A, Haghdoost AA, Rezaei-nassab M, et al. Relative frequency of animal rabies and factors affecting it in Kerman province, 1993-2003. J School Pub Health Instit Pub Health Res. 2007;5:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tadjbakhsh H. Tehran: Tehran University Press and Veterinary Organization Press; 1994. The history of veterinary medicine and medicine in Iran; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharifian J. Tehran: Seminar of rabies In sciences Academy; 2006. Rabies and surveillance of rabies and animal bites in iran; pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeinali A, Tajik P, Rad MA. Tehran: 2002. Disease of wild animals; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadin-Davis SA, Simani S, Armstrong J, Fayaz A, Wandeler AI. Molecular and antigenic characterization of rabies viruses from Iran identifies variants with distinct epidemiological origins. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:777–90. doi: 10.1017/s095026880300863x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeynali M, Fayaz A, Nadim A. Animal bites and rabies situation in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 1999;2:120–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sriaroon C, Sriaroon P, Daviratanasilpa S, Khawplod P, Wilde H. Retrospective: Animal attacks and rabies exposures in Thai children. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2006;4:270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanganeh AM, Maqsoudlo Esterabadi S, Malvandi A. Annually statistics of Golestan Health center in 2008-2009. :79–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amiri M, Khosravi A. Epidemiological study of animal bite cases in the Shahrood city- J Knowledge Health. 2009;4:41–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikholeslami NZ, Rezaeian M, Salem Z. Epidemiology of animal bites in Rafsanjan, southeast of Islamic Republic of Iran, 2003-05. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:455–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fevre EM, Kaboyo RW, Persson V, Edelsten M, Coleman PG, Cleaveland S. The epidemiology of animal bite injuries in Uganda and projections of the burden of rabies. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:790–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatami G, Motamed N, Zia sheikh eslami N. A survey on animal bite in children less than 16 years old in Bushehr; 2001-2006. Iran South Med J. 2007;9:182–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichhpujani RL, Mala C, Veena M, Singh J, Bhardwaj M, Bhattacharya D, et al. Epidemiology of animal bites and rabies cases in India. A multicentric study. J Commun Dis. 2008;40:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahonar AR, Bokaie S, Khodaveirdi KH, Nikbakht Boroujeni GH, Rad MA. A Study of Rabies and the Frequency of Animal Bites in the Province of Ilam, 1994-2004. Iranian J Epid. 2008;4:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoboobati MM, Dehghani MH, Sarvat F. A ten years record of animal bite cases of patients referred to Nikoopour health center, Yazd, 1990-1999. J Yazd Uni Med Sci. 2002;9:117–20. [Google Scholar]