Abstract

Hooking up, or engaging in sexual interactions outside of committed relationships, has become increasingly common among college students. This study sought to identify predictors of sexual hookup behavior among first-year college women using a prospective longitudinal design. We used problem behavior theory (Jessor, 1991) as an organizing conceptual framework and examined risk and protective factors for hooking up from three domains: personality, behavior, and perceived environment. Participants (N = 483, 67% White) completed an initial baseline survey that assessed risk and protective factors, and nine monthly follow-up surveys that assessed the number of hookups involving performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, and vaginal sex. Over the course of the school year, 20% of women engaged in at least one hookup involving receiving oral sex, 25% engaged in at least one hookup involving performing oral sex, and 25% engaged in at least one hookup involving vaginal sex. Using two-part modeling with logistic and negative binomial regression, we identified predictors of hooking up. Risk factors for sexual hookups included hookup intentions, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, pre-college hookups, alcohol use, marijuana use, social comparison orientation, and situational triggers for hookups. Protective factors against sexual hookups included subjective religiosity, self-esteem, religious service attendance, and having married parents. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, hookup attitudes, depression, cigarette smoking, academic achievement, injunctive norms, parental connectedness, and being in a romantic relationship were not consistent predictors of sexual hookups. Future research on hookups should consider the array of individual and social factors that influence this behavior.

Keywords: hooking up, casual sex, sexual behavior, college students, women

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a new cultural phenomenon regarding romantic and sexual relationships has emerged, namely, sexual hookups. Hooking up has been studied primarily among American college students and has received considerable attention in both the popular media (e.g., Stepp, 2007) and the research literature (for reviews, see Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2012; Heldman & Wade, 2010; Stinson, 2010). In this article, we briefly summarize the burgeoning research literature on hooking up, and then describe a longitudinal study designed to identify theoretically-suggested antecedents of sexual hookups among first-year college women.

Defining Sexual Hookups

There is no single, universally-accepted definition of hookups (Brimeyer & Smith, 2012; LaBrie, Hummer, Ghaidarov, Lac, & Kenney, 2012; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lewis, Atkins, Blayney, Dent, & Kaysen, 2012a); however, most young people share similar scripts for hookups. Qualitative research suggests three main features of hookups: (1) a variety of sexual behaviors, from kissing to penetrative intercourse, may occur, (2) the partners are not in a committed relationship, and (3) the interaction is short-term and does not signify that a romantic relationship will begin (Epstein, Calzo, Smiler, & Ward, 2009). Consistent with this qualitative research, most scholars share a consensus on the definition and operationalize hookups as sexual encounters between partners who are not in a romantic relationship and do not expect commitment (e.g., Heldman & Wade, 2010; Holman & Sillars, 2012; LaBrie et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012a; Lewis, Granato, Blayney, Lostutter, & Kilmer, 2012b; Stinson, 2010).

Hooking up is similar to “friends with benefits” (FWB) in that both involve sexual encounters outside of the context of a romantic relationship. Some argue that FWB are distinct from hookups because of the established friendship between the partners (Lehmiller, VanderDrift, & Kelly, 2012). However, hookups most often occur with friends (Fielder & Carey, 2010b), and FWB are not necessarily friends in the usual sense (Mongeau et al., 2013). Thus, FWB may be a subtype of hooking up, rather than a distinct phenomenon.

Emergence of Hookup Culture

Research on hookups did not begin to appear until 2000 (Stinson, 2010). A number of scholars have suggested that hooking up differs from casual sex and that it has emerged as a new culture among college students (Aubrey & Smith, 2011; Bogle, 2008; Heldman & Wade, 2010; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Reiber & Garcia, 2010). Several differences are noteworthy. First, hooking up and casual sex have been defined differently. Casual sex is often defined as meeting a partner and having sexual intercourse that same day, having sexual intercourse with a partner once and only once, or having sexual intercourse without emotional commitment (Herold, Maticka-Tyndale, & Mewhinney, 1998; Weaver & Herold, 2000). In contrast, the term hookup is used to refer to a variety of sexual behaviors (i.e., broader than just vaginal sex), and hookup partners usually know each other (e.g., friends) and may hook up on multiple occasions (Fielder & Carey, 2010b). A second difference is the high prevalence (i.e., 70-80%) of hookup behavior; hooking up is done openly (Garcia & Reiber, 2008) and appears to be a normative experience for young people attending college today (Garcia et al., 2012; Stinson, 2010). A third difference is the accompanying desire to delay or avoid romantic relationships among emerging adults (Heldman & Wade, 2010) in favor of focus on self-development during the college years (Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009). Thus, although hooking up and casual sex both entail a lack of commitment, they appear to be distinct. Casual sex can be considered a form of hooking up.

Prevalence of Hookup Behavior

Hooking up is common among college students (Hollman & Sillars, 2012), leading some to suggest that it may be replacing traditional dating as the modal way to explore romantic/sexual relationships on college campuses (Bradshaw, Kahn, & Saville, 2010; Stinson, 2010). Yet, recent research suggests that hooking up is supplementing, rather than supplanting, traditional courtship patterns, as it was found to be less common than dating (Brimeyer & Smith, 2012) and sex within romantic relationships (Fielder, Carey, & Carey, 2012). Most studies have found that 70-80% of college students reported lifetime hookup experience (Aubrey & Smith, 2011; Lambert, Kahn, & Apple, 2003; McClintock, 2010; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Paul, McManus, & Hayes, 2000), and 52-70% reported hookups in the last semester or last year (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Owen, Fincham, & Moore, 2011; Owen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Fincham, 2010). Three studies assessing the prevalence of specific sexual behaviors in hookups have found that 51-60% of college students have lifetime oral or vaginal sex hookup experience (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Fielder et al., 2012; Gute & Eshbaugh, 2008).

Public Health Significance of Sexual Hookups

Hooking up has the potential to confer both positive and negative consequences. The former may include feeling attractive, desirable, and empowered; experiencing sexual pleasure, excitement, and fun; feeling close to someone momentarily; and meeting new friends or potential romantic partners (Bachtel, 2013; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Paul, 2006; Plante, 2006). Event-level studies have shown that men and women report more positive emotional reactions than negative (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Lewis et al., 2012b; Owen & Fincham, 2011), and more than half of women reported being content with their decision to hook up with their most recent partner (LaBrie et al., 2012). At the same time, negative health outcomes are also possible (Lewis et al., 2012b). Among women, research documents an association between hookup behavior and depressive symptoms (Grello, Welsh, & Harper, 2006), low self-esteem (Paul et al., 2000), and sexual regret (Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008). Women may be more vulnerable than men to emotional distress after hookups due to their greater desire for hookups to become romantic relationships (Owen & Fincham, 2011), pressure from male hookup partners to go further sexually than they want (Paul & Hayes, 2002), and a muted but persistent sexual “double standard” (Bogle, 2008; Paul, 2006; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Preliminary evidence also indicates that hooking up may increase women’s risk of experiencing sexual victimization (Flack et al., 2007; Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, 2010). In addition, hookup behavior likely increases risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) due to the frequent occurrence of oral and vaginal sex, inconsistent condom use during vaginal sex, near-zero rates of condom use during oral sex, and the likelihood for multiple and/or concurrent partners (Downing-Matibag & Geisinger, 2009; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Lewis et al., 2012b). It is important to note that most research on hookup consequences has been qualitative or cross-sectional and has failed to measure positive outcomes; therefore, additional research is needed before we can draw strong conclusions about the health risks of hookups.

Conceptual Framework

The literature on correlates and predictors of hooking up has grown considerably over the past decade (Garcia et al., 2012; Heldman & Wade, 2010). Nonetheless, most studies have been cross-sectional (for exceptions, see Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). Moreover, almost all research has been atheoretical, limiting the coherence of the literature and the interpretation of findings. To guide our study of hookup predictors, we adopted Jessor’s (1991) problem behavior theory (PBT) as an organizing conceptual framework. In the absence of a sexuality-specific framework, the broader (health-)behavioral model provides a useful heuristic framework. This framework has been used previously to identify psychosocial and behavioral risk and protective factors for other health behaviors among college students (e.g., smoking) (Costa, Jessor, & Turbin, 2007) and has received substantial empirical support (Donovan, 2005).

In the PBT approach, problem behaviors are socially defined as concerning or undesirable by conventional standards. From this perspective, sexual hookups can be considered problem behaviors insofar as they involve unprotected sex, multiple partners, sex while intoxicated, or sexual victimization, all of which can have negative health consequences. Not all hookups involve these risks, but many do (England & Thomas, 2006; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Flack et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2012b); therefore, although sexual exploration is developmentally appropriate for emerging adults (Tolman & McClelland, 2011), hooking up may be a health-compromising behavior because of these associated health consequences.

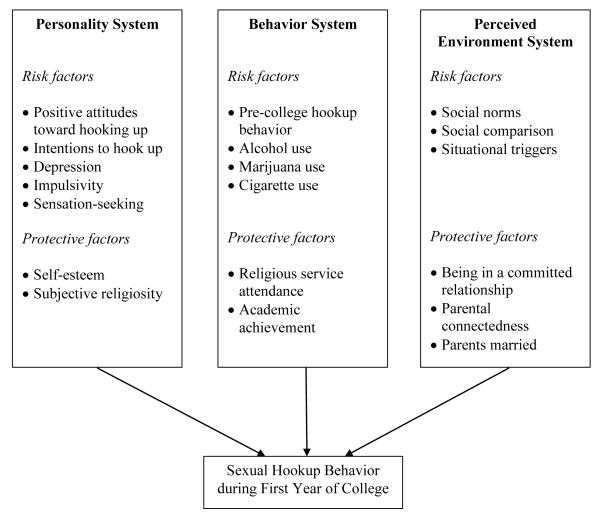

The most recent articulation of PBT (Jessor, 1991) organizes the antecedents of behavior into risk and protective factors. Risk factors increase the likelihood of engaging in problem behaviors, whereas protective factors decrease the likelihood of engaging in problem behaviors and attenuate the effects of risk factors. In addition to considering individual differences, PBT incorporates the influence of the various social contexts in which youth exist, such as family and peers. Thus, the major systems of explanatory variables in PBT include (1) personality, (2) behavior, and (3) perceived environment (Donovan, 2005). Next, we organize and review research on the antecedents of hooking up according to this framework (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework Based on Problem Behavior Theory

Personality System

Risk factors. Little research has examined the influence of attitudes and behavioral intentions on hooking up. Two studies have found that positive attitudes toward sex or hooking up were positively correlated with hookup behavior (Olmstead, Pasley, & Fincham, 2012; Owen et al., 2010). Behavioral intentions, which have a central role in many theories of health behavior (Webb & Sheeran, 2006), have not been examined with respect to hookups.

Early research suggested a link between hookups and emotional distress; depressive symptoms were positively correlated with hookup behavior (Grello et al., 2006). In contrast, more recent research has found no correlation between distress or depressive symptoms and hookups (Owen & Fincham, 2011; Owen et al., 2010). Moreover, depressive symptoms did not predict hookup behavior in two longitudinal studies (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). Depression may be a risk factor for hooking up if students use hookups to try to improve their mood and cope with stress (Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998). Although we did not address this in the current study, it is also possible that depression may follow, rather than precede, hookups.

There is a dearth of research on personality traits and hooking up. An early study found that impulsivity was positively correlated with hooking up (Paul et al., 2000), but subsequent research has ignored this variable despite its association with sexual risk behavior among young women (Kahn, Kaplowitz, Goodman, & Emans, 2002). A recent study found that sensation-seeking was positively correlated with receiving oral sex, but not performing oral sex or having vaginal sex, during hookups (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013).

Protective factors. Little research has explored protective factors against hooking up. In one study, self-esteem was negatively correlated with hookup behavior (Paul et al., 2000), but in two recent longitudinal studies self-esteem did not predict hookup behavior (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). High self-esteem may confer confidence to resist external pressures to hook up. Subjective religiosity is hypothesized to be a protective factor against numerous health behaviors because it provides social control and support for pro-social behaviors. However, subjective religiosity was not correlated with hookups in two cross-sectional studies (Burdette, Ellison, Hill, & Glenn, 2009; Penhollow, Young, & Bailey, 2007) and did not predict hookup behavior in two longitudinal studies (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011).

Behavior System

Risk factors. Two of the most consistent risk factors for hooking up are previous hookup behavior and alcohol use (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). Previous hookup behavior provides a personal model for future behavior (Ouellette & Wood, 1998), and alcohol use increases contextual vulnerability for hookups to occur (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Vander Ven & Beck, 2009). At least six studies have found positive correlations between alcohol use and hooking up (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Gute & Eshbaugh, 2008; Olmstead et al., 2012; Owen & Fincham, 2011; Owen et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2000). We know of no research that has examined marijuana use or cigarette smoking, two behaviors that are often correlated with alcohol use (Costa et al., 2007) and may have similar functions (e.g., social enhancement, coping) with respect to hooking up. Substance use may increase risk for hookup behavior by providing opportunities and encouragement to engage in other risk behaviors, which are often learned and practiced together (Jessor, 1991).

Protective factors

Behavioral protective factors, such as religious and academic involvement, constitute pro-social activities, engender socialization of conventional values, and promote linkages with conventional social groups (Donovan, 2005). Two studies found that religious service attendance was negatively correlated with hookups (Burdette et al., 2009; Penhollow et al., 2007); however, after controlling for covariates, it did not predict hookup behavior in two longitudinal studies (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). We know of no research that has examined academic achievement and hooking up; academic involvement may buffer against hooking up by displacing time that may otherwise be used for socializing.

Perceived Environment System

Risk factors

Research suggests an important role for the social context of hookup behavior (Holman & Sillars, 2012), but few studies have assessed potential risk factors from the environmental system. College students have inflated perceived norms about peers’ sexual behavior, including hookups (Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lambert et al., 2003), and perceived norms are associated with personal sexual behavior (Lewis, Lee, Patrick, & Fossos, 2007). Only two studies have explored social norms as a correlate or predictor of hookups, with mixed findings (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Fielder & Carey, 2010a). Related to norms, a high level of social comparison orientation, or the degree to which one compares his or her behavior with others’ behavior, is also hypothesized to be a risk factor for hooking up. Lastly, the situational context (e.g., others hooking up) may also increase risk for hookup behavior by providing models of risk behavior and increasing personal and social vulnerability (Downing-Matibag & Geisinger, 2009). Situational triggers for hookups were a multivariate predictor of oral and vaginal sex hookup behavior in a recent longitudinal study (Fielder & Carey, 2010a).

Protective factors

Involvement in a committed relationship may protect against hookup behavior due to loyalty or concern for a romantic partner. Among college men, those in committed romantic relationships were less likely to hook up compared to those who were single (Olmstead et al., 2012). Another important social context that may influence hookup behavior is the family, but no studies have examined the role of parental connectedness. Parents may protect against hookup behavior by providing social control and discouraging risk behaviors. Twenty percent of U.S. college students reported that their parents were divorced (Helweg-Larsen, Harding, & Klein, 2011). Having parents who are married may protect against hookups by providing models of conventional relationships and sexual behavior. However, two previous studies found no significant association between parental marital status and hookup behavior (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2010).

The Present Study

In summary, most extant research on correlates and predictors of hooking up has focused on individual-level factors to the exclusion of social and contextual influences. Findings from cross-sectional studies have been equivocal, and only two longitudinal studies have examined predictors of hooking up. Owing to the newness of this research area, most extant research has been atheoretical and exploratory. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify risk and protective factors for sexual hookup behavior among first-year college women. We sampled women because they are more vulnerable to the potential health consequences of hookups compared to men. We focused on first-year students because the transition from high school to college is an important developmental context in which risky behaviors, such as alcohol use and sexual behavior, tend to increase (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008). Given the potential for negative mental and physical health outcomes (Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Owen et al., 2010; Testa et al., 2010), it is important to identify the factors that influence hookup behavior. We advance the literature by using a conceptual framework to select predictors, following a large sample of college women during an important developmental transition, and using a prospective longitudinal design with monthly surveys over one year.

Hypotheses

Based on prior research and theory, we expected positive associations between sexual hookups during the first year of college and these risk factors: attitudes toward hooking up, behavioral intentions, depression, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, pre-college hookup behavior, alcohol use, marijuana use, cigarette use, injunctive norms, social comparison orientation, and situational triggers. We expected negative associations between sexual hookups and these protective factors: self-esteem, subjective religiosity, religious service attendance, academic achievement, being in a committed relationship, parental connectedness, and having married parents.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 483 incoming first-year female undergraduates attending a private university in upstate New York. Women under age 18 or over age 25 years at baseline and scholarship athletes were excluded. Scholarship athletes were ineligible due to National Collegiate Athletic Association restrictions on payments to student-athletes, and women over age 25 were excluded due to our focus on emerging adults. Per university data, the sample of 483 women constituted 26% of incoming first-year female students that year, with an equivalent ethnic breakdown. Most participants (94%) were 18 years old at baseline (M = 18.1, SD = 0.3, range: 18-21). The racial/ethnic distribution of the sample was 67% White, 12% Asian, 12% Black, and 9% Hispanic/Latina. Almost all (96%) participants identified as heterosexual. Women completed an average of 8.74 surveys out of 9 (SD = 0.87, median = 9, range: 1-9). Response rates for the follow-up surveys ranged from a low of 85% at Wave 9 to a high of 97% at Wave 2.

Procedure

We used a prospective longitudinal design with one baseline (T1) and 8 monthly follow-ups (T2-T9). The study spanned the first academic year at a residential college. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Recruitment began with a mass mailing to 1,400 incoming first-year female students. Scholarship athletes, students under age 18, and international students were excluded from the mailing due to ineligibility and uncertain timing of mail delivery to foreign addresses, respectively. Flyers, word of mouth, and the psychology department research pool were also used to supplement recruitment. The study was described to prospective participants as focusing on women’s health behaviors and relationships. Recruitment materials invited women to sign up on a website to receive further information about the study; women were then invited to attend orientation sessions during their first three weeks on campus. Most participants (61%) heard about the study through the mass mailing, 28% signed up through the psychology department research pool, and 11% responded to flyers or word of mouth.

At the orientation sessions, the study was described to participants as involving surveys about personality, mood, relationships, sexual behavior, and health behaviors, such as sleep, physical activity, and substance use. Given that most participants were under age 21 and were asked to report on their alcohol and drug use, we obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality for this research. We explained to participants that all surveys were confidential, and their names would not be associated with their survey responses. Survey responses were linked over time using unique identification codes, and identifying information was stored separately from survey responses to protect privacy.

After providing written informed consent, participants completed the baseline survey on private computers, for which they received $20. All study data were collected through a secure online survey software program. Follow-up surveys began at the end of September 2009 (T2) and continued through the end of May 2010 (T9). On the last day of each month, participants received an email with an embedded confidential survey, which they had one week to complete. They received $10 for each follow-up survey completed. Surveys were designed to be completed in 20 minutes or less. To prompt timely responding, participants were entered in a monthly raffle for two $50 cash prizes, with the number of raffle entries decreasing as response lag increased.

Measures

All predictors were assessed at baseline unless otherwise noted.

Demographics

Participants indicated their age, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed at T8 using a 10-point ladder (Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000), on which participants ranked their family relative to other American families. Race/ethnicity and SES were used as control variables. Age and sexual orientation were not included as control variables due to a lack of variability.

Personality system

Risk factors. Hookup attitudes were measured using four items adapted from a study of college student alcohol norms (Rimal & Real, 2005). Participants indicated their agreement with four items on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree): (1) I believe that hooking up is a part of the college experience, (2) I expect to hook up in college, (3) I believe that freshmen look forward to hooking up at college, and (4) I believe that hooking up is important to college students’ social lives. Responses were averaged (α = .78).

Hookup intentions were measured using two face-valid items. Participants indicated their agreement with each item (e.g., “I plan to have oral [vaginal] sex with a casual partner during the Fall 2009 semester”) on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We used oral sex intentions as a predictor of hookups involving performing and receiving oral sex and vaginal sex intentions as a predictor of hookups involving vaginal sex.

Depression was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). Participants indicated how often they were bothered by each symptom (e.g., “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”) over the last two weeks using a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores were summed to create a total score (α = .80) ranging from 0 to 27.

Impulsivity was measured using six items (Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007) from the Impulsiveness subscale of the Impulsiveness-Monotony Avoidance Scale (Schalling, 1978). Participants indicated how well each item (e.g., “I often throw myself too hastily into things”) applied to them on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). Scores were summed to create a total score (α = .82) ranging from 6 to 24.

Sensation-seeking was measured using six items (Magid et al., 2007) from the Monotony Avoidance subscale of the Impulsiveness-Monotony Avoidance Scale (Schalling, 1978). Participants indicated how well each item (e.g., “I like doing things just for the thrill of it”) applied to them on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). Scores were summed to create a total score (α = .82) ranging from 6 to 24.

Protective factors. Self-esteem was measured with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants indicated their agreement with each item (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Five negatively-worded items were reverse-scored, and scores were summed to create a total score (α = .89) ranging from 10 to 40.

Subjective religiosity was measured with the global religiosity self-ranking item from the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (Fetzer Institute, 1999). Participants were asked to what extent they consider themselves religious on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not religious at all) to 4 (very religious).

Behavior system

Risk factors

See below for measure of pre-college hookup behavior.

For alcohol use, we assessed frequency of binge drinking (number of days) in the last month, with anchor dates provided to facilitate recall. Standard drinks were defined according to published standards (Dufour, 1999), and participants indicated on how many days in the last month they had four or more drinks on one occasion. For marijuana use, we assessed frequency of use (number of days) in the last month, with anchor dates provided to facilitate recall. For cigarette use, women reported on whether they had smoked in the month prior to college entry; if they had, they reported the number of cigarettes they smoked each day in a typical week during that month. These daily reports were averaged, and women who reported smoking one or more cigarettes per day on average were classified as smokers.

Protective factors

Religious service attendance was measured with one item asking the frequency with which participants attend religious services, on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 6 (more than once a week). For academic achievement, participants indicated their high school grade point average (GPA) on a 4.0 scale.

Perceived environment system

Risk factors

Injunctive norms were measured using four items adapted from a study of college student alcohol norms (Rimal & Real, 2005). Participants indicated their agreement with four items on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree): (1) The people I know believe that hooking up is a part of the college experience, (2) The people I know expect me to hook up in college, (3) The people I know believe that freshmen look forward to hooking up at college, and (4) The people I know believe that hooking up is important to college students’ social lives. Responses were averaged (α = .83).

Social comparison orientation was measured using the six items that constitute the Ability factor of the Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM) (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999). Participants indicated their agreement with each item (e.g., “I always pay a lot of attention to how I do things compared with how others do things”) on a Likert scale from 1 (I disagree strongly) to 5 (I agree strongly). One negatively-worded item was reverse-scored, and scores were summed to create a total score (α = .83) ranging from 5 to 25.

Situational triggers were assessed at T2 with three items adapted from a study of casual sex among college students (Herold et al., 1998). Participants rated how likely, on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 6 (extremely likely), they would be to hook up with a casual partner in three situations: (1) When you are at a bar or party, (2) When someone attractive wants to hook up with you, and (3) When it seems like everyone else is hooking up. Responses were averaged (α = .91).

Protective factors

Participants indicated their relationship status (single or in a committed relationship) and their parents’ marital status (married or other).

Parental connectedness was assessed at T2 with eight items adapted from the Involvement subscale of the Parenting Style Index (Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992). Participants rated their agreement with each item (e.g., “My parents spend time just talking with me”) on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged (α = .90).

Hookup behavior

Measures of sexual behavior followed published guidelines to optimize reliability and validity (Weinhardt, Forsyth, Carey, Jaworski, & Durant, 1998). Hookup behavior was assessed at every occasion using items adapted from previous research (Fielder & Carey, 2010a, 2010b). A sexual hookup was operationally defined as oral or vaginal sex with a casual partner; this definition reflects the extant research on partner types, sexual behaviors, and the defining characteristic of a hookup (Epstein et al., 2009; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Use of the word hookup was intentionally minimized to reduce the potential for proactive interference, which may cause participants to respond with their idiosyncratic understandings of the term in mind. Thus, participants were asked about engaging in specific sexual behaviors (i.e., oral and vaginal sex) with casual partners (Fielder et al., 2012). A casual partner was defined as “someone whom you were not dating or in a romantic relationship with at the time of the physical intimacy, and there was no mutual expectation of a romantic commitment. Some people call these hookups.” This assessment strategy was selected to reduce ambiguity in interpretations of questions about hookup behavior (cf. Garcia et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012a) while still capturing its essence.

Participants were first asked about physical intimacy (“closeness with a partner that might include kissing, sexual touching, or any type of sexual behavior”) with casual partners; those who indicated one or more partners or who left the question blank proceeded to questions about oral and vaginal sex. Oral sex was defined as “when either partner puts their mouth on the other partner’s genitals,” and vaginal sex was defined as “when a man puts his penis in a woman’s vagina.” Three items assessed the number of oral sex (performed), oral sex (received), and vaginal sex hookup events within a given time interval. At baseline (T1), participants were asked about their lifetime prior to college; at subsequent monthly assessments (T2-T9), participants were asked about the last month, with anchor dates provided to facilitate recall.

We created predictor variables related to pre-college hookups of three types: performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, and vaginal sex. These were binary variables representing whether women had engaged in at least one hookup of each type. As our outcome variables, counts of number of hookup events during the academic year were created by summing monthly reports from T2 to T9. Sums were created for performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, and vaginal sex. Because there was a small amount of missing data (an average of 0.68 points per woman), we replaced missing months with each woman’s individual monthly mean of hookup events.

Data Analysis

All variables were examined for univariate and multivariate outliers by inspecting box plots and examining Mahalanobis distance. Univariate outliers were recoded to three SDs from the mean. No multivariate outliers were identified. Because hookup events were reported over the course of 8 months, monthly reports were missing for between 4 and 15% of participants; a small percentage of reports (from 0 to 12%) of predictor variables were also missing. Women with missing data were more likely to be Black, χ2(1) = 8.41, p < .01, and had lower high school GPAs, t(482) = 3.91, p < .001. Women with missing data were also more likely to have engaged in a vaginal sex hookup prior to college, χ2(1) = 4.15, p < .05. There were no significant differences in other demographic variables, or in probability of pre-college oral sex hookups. As noted above, to avoid potential bias from excluding women with missing data, missing monthly reports of hookup events were replaced with women’s individual monthly means. Other missing values were dealt with using multiple imputation (Rubin, 1996; Schafer, 1997), a modern method for dealing with missing data that avoids biases associated with using only complete cases or with single imputations (Schafer, 1999). The R program Amelia (Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2011), which allows for both continuous and binary imputations, was used to create 100 imputations. We used Mplus version 5 for the analyses (Muthén & Muthén, 2007).

Logistic and negative binomial regressions were used to examine predictors of hookup events. We predicted separately the probability of engaging in any hookup event (a binary variable) and the number of hookups engaged in (for women reporting hookups; a zero-truncated negative binomial variable). Separate models were created for performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, and vaginal sex. All predictors were entered into the regressions; regression weights for highly non-significant predictors (T > 1) were fixed at zero to stabilize estimates. We report odds ratios or unstandardized beta weights along with 95% confidence intervals. R2 values are also reported for the logistic regressions; they are not available for negative binomial regressions.

RESULTS

Descriptive information on predictor variables is shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows zero-order correlations between all predictor variables and: (1) any hookups and (2) number of hookups of all three types.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information on Study Variables

| M (SD) or % | Observed Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Asian | 12% | -- |

| Black | 12% | -- | |

| Latina | 9% | -- | |

| Socioeconomic status | 6.23 (1.67) | 1-10 | |

| Personality System |

Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup attitudes | 2.44 (0.70) | 1-4 | |

| Hookup intentions (oral sex) | 1.77 (1.51) | 1-7 | |

| Hookup intentions (vaginal sex) | 1.68 (1.47) | 1-7 | |

| Depression | 5.43 (4.07) | 0-18 | |

| Impulsivity | 12.67 (3.88) | 6-24 | |

| Sensation-seeking | 17.18 (3.77) | 6-24 | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Self-esteem | 32.77 (5.49) | 16-40 | |

| Subjective religiosity | 2.21 (0.92) | 1-4 | |

| Behavior System | Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-college hookups (performing oral sex) | 26% | -- | |

| Pre-college hookups (receiving oral sex) | 21% | -- | |

| Pre-college hookups (vaginal sex) | 21% | -- | |

| Frequency of binge drinking | 2.10 (3.27) | 0-13 | |

| Frequency of marijuana use | 1.21 (2.95) | 0-14 | |

| Cigarette smoking | 10% | -- | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Religious service attendance | 2.66 (1.42) | 1-6 | |

| High school grade point average | 3.62 (0.29) | 2.8-4 | |

| Perceived Environment System |

Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup injunctive norms | 2.88 (0.71) | 1-4 | |

| Social comparison orientation | 20.93 (4.89) | 6-30 | |

| Situational triggers | 2.51 (1.43) | 1-6 | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Committed relationship | 29% | -- | |

| Parental connectedness | 3.45 (0.51) | 1.78-4 | |

| Parents married | 66% | -- |

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations between Predictor Variables and Hookup Behaviors

| Any Hookups | Number of Hookups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Performed Oral Sex |

Received Oral Sex |

Vaginal Sex |

Performed Oral Sex |

Received Oral Sex |

Vaginal Sex |

|

| Asian | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.08 | −.18+ | −0.11 |

| Black | −.08+ | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.1 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Latina | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.07 |

| Socioeconomic status | 17*** | .10* | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| HU attitudes | 30*** | .26*** | 28*** | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| HU intentions – Oral | 38*** | .36*** | .35*** | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| HU intentions – Vaginal | 30*** | 30*** | .36*** | 0.04 | 0.13 | .20* |

| Depression | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | .17+ | −0.11 | 0.05 |

| Impulsivity | .12** | 0.07 | 14** | .16+ | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| Sensation-seeking | 0.05 | .11* | .12** | −0.02 | 0.17 | .23* |

| Self-esteem | −0.06 | −0.05 | −.08+ | −.25** | 0.15 | −0.09 |

| Subjective religiosity | −21*** | − 17*** | −23*** | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.07 |

| Pre-coll. HU – Oral P. | 48*** | 37*** | 42*** | 37*** | .25* | 29** |

| Pre-coll. HU – Oral R. | .37*** | 37*** | 39*** | 29*** | .26** | .26** |

| Pre-coll. HU – Vaginal | .38*** | .33*** | .50*** | 24** | .19+ | .25** |

| Freq. binge drinking | 34*** | 28*** | .26*** | 0.07 | .19+ | 0.08 |

| Freq. marijuana use | .37*** | .36*** | .33*** | 29*** | 0.15 | .25** |

| Cigarette smoking | .10* | 15*** | .13** | 27** | −0.08 | .17+ |

| Religious attendance | −.18*** | −.12** | −21*** | −0.04 | −0.13 | 0.11 |

| High school GPA | −.10* | −.08+ | −.09+ | −0.12 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| HU injunctive norms | 18*** | .18*** | 22*** | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Social comparison | .12** | 0.07 | .12** | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Situational triggers | .35*** | 30*** | 34*** | .21* | 0.05 | .17+ |

| Committed relationship | −.11* | −.12** | −0.06 | −0.06 | .22* | −0.09 |

| Parental connectedness | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Parents married | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.09 |

Note. HU = hookup; Pre-coll. = pre-college; Oral P. = performed oral sex; Oral R. = received oral sex; Freq. = frequency of; GPA = grade point average.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Frequency of Hookups during the First Year of College

Over the course of the school year, 25% of women engaged in at least one hookup involving performing oral sex, 20% in at least one hookup involving receiving oral sex, and 25% in at least one hookup involving vaginal sex. Among those engaging in each type of hookup, women reported an average of 6.1 (SD = 5.5) hookups involving performing oral sex (median = 3, range: 1-18), 3.7 (SD = 3.0) hookups involving receiving oral sex (median = 2, range: 1-11), and 6.6 (SD = 6.0) hookups involving vaginal sex (median = 3, range: 1-20).

Predictors of Hookups Involving Performing Oral Sex

A number of risk and protective factors predicted hookups involving performing oral sex (Table 3); these findings were consistent with our hypotheses unless otherwise noted. We first examined predictors of engaging in any hookups involving performing oral sex during the academic year. In the personality system, women with stronger intentions to engage in oral sex hookups at baseline were more likely to hook up during the school year. In contrast, women reporting higher levels of subjective religiosity were less likely to engage in hookups involving performing oral sex. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college hookups involving oral sex, who binge drank more frequently, and who used marijuana more frequently were more likely to engage in hookups involving performing oral sex. In contrast, and contrary to our hypothesis, women who smoked cigarettes were less likely to engage in hookups involving performing oral sex. Finally, in the perceived environment system, women with a stronger social comparison orientation and who reported more situational triggers were more likely to engage in hookups involving performing oral sex. Collectively, predictors explained 46% of the variance in engaging in hookups involving performing oral sex.

Table 3.

Predictors of Engagement in Hookups Involving Performing Oral Sex

| Any Hookups (Performing Oral Sex) |

Number of Hookups (Performing Oral Sex)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| OR [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | ||

| Demographics | Asian | --- | −0.49 [−1.15,0.17] |

| Black | --- | −0.85 [−1.78,0.08]+ | |

| Latina | 1.72 [0.66,4.49] | −0.45 [−1.00,0.11] | |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.10 [0.92,1.33] | --- | |

| Personality System | Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup attitudes | 1.41 [0.77,2.58] | --- | |

| Hookup intentions | 1.22 [1.03,1.44]* | --- | |

| Depression | --- | --- | |

| Impulsivity | --- | --- | |

| Sensation-seeking | --- | --- | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Self-esteem | --- | −0.03 [−0.06,−0.002]* | |

| Subjective religiosity | 0.65 [0.48,0.88]** | --- | |

| Behavior System | Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-college hookups | 5.20 [2.88,9.39]*** | 0.65 [0.23,1.08]** | |

| Freq. binge drinking | 1.10 [1.01,1.20]* | --- | |

| Freq. marijuana use | 1.16 [1.06,1.27]*** | 0.05 [0.01,0.09]* | |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.42 [0.18,0.99]* | 0.36 [−0.06,0.78]+ | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Religious service attend. | --- | --- | |

| High school GPA | --- | −0.47 [−1.12,0.18] | |

| Perceived Environment System |

Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup injunctive norms | 0.70 [0.40,1.20] | −0.36 [−0.72,0.01]+ | |

| Social comparison | 1.07 [1.01,1.14]* | --- | |

| Situational triggers | 1.25 [1.001,1.57]* | --- | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Committed relationship | --- | --- | |

| Parental connectedness | --- | --- | |

| Parents married | --- | −0.44 [−0.82,−0.06]* | |

|

| |||

| R 2 | .46 [.37,.56]*** | -- | |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; B = regression estimate; Freq. = frequency of; Attend. = attendance; GPA = grade point average. Two-part modeling looked at the probability of experiencing any oral sex hookup and the number of oral sex hookups given at least one occurred. All predictors were entered into the regressions; regression weights for highly non-significant predictors (T > 1) were fixed at zero to stabilize estimates. All remaining coefficients are reported. Significant predictors appear in boldface type.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

For those reporting at least one oral sex hookup.

We next examined predictors of the number of hookups involving performing oral sex for women engaging in at least one hookup (Table 3). In the personality system, women with higher self-esteem engaged in fewer hookups involving performing oral sex. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college oral sex hookups and used marijuana more frequently engaged in more hookups involving performing oral sex. Finally, in the perceived environment system, women whose parents were married engaged in fewer hookups involving performing oral sex.

Predictors of Hookups Involving Receiving Oral Sex

Risk and protective factors also predicted hookups involving receiving oral sex (Table 4); these findings were consistent with our hypotheses unless otherwise noted. We first examined predictors of engaging in any hookups involving receiving oral sex during the academic year. In the personality system, women with stronger intentions to engage in oral sex hookups at baseline were more likely to hook up during the school year. In contrast, women reporting higher levels of subjective religiosity were less likely to engage in hookups involving receiving oral sex. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college oral sex hookups and who used marijuana more frequently were more likely to engage in hookups involving receiving oral sex. In the perceived environment system, women with a stronger social comparison orientation were more likely to engage in hookups involving receiving oral sex. Additionally, Black women were more likely to engage in hookups involving receiving oral sex. Collectively, predictors explained 38% of the variance in engaging in hookups involving receiving oral sex.

Table 4.

Predictors of Engagement in Hookups Involving eing Oral Sex

| Any Hookups (Receiving Oral Sex) |

Number of Hookups (Receiving Oral Sex)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| OR [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | ||

| Demographics | Asian | 2.03 [0.87,4.74]+ | −1.06 [−1.81,−0.31]** |

| Black | 2.41 [1.07,5.46]* | --- | |

| Latina | --- | −0.36 [−0.84,0.11] | |

| Socioeconomic status | --- | --- | |

| Personality System | Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup attitudes | --- | --- | |

| Hookup intentions | 1.25 [1.05,1.49]** | --- | |

| Depression | --- | −0.05 [−0.09,−0.01]* | |

| Impulsivity | 0.93 [0.86,1.01]+ | 0.06 [0.0002,0.12]* | |

| Sensation-seeking | 1.06 [0.99,1.15] | 0.04 [−0.01,0.08] | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Self-esteem | --- | --- | |

| Subjective religiosity | 0.73 [0.54,0.98]* | --- | |

| Behavior System | Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-college hookups | 4.53 [2.41,8.52]*** | 0.47 [0.01,0.09]* | |

| Freq. binge drinking | 1.08 [0.99,1.18]+ | 0.05 [0.01,0.09]** | |

| Freq. marijuana use | 1.18 [1.07,1.29]*** | --- | |

| Cigarette smoking | --- | −0.32 [−0.78,0.14] | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Religious service attend. | --- | −0.18 [−0.30,−0.05]* | |

| High school GPA | --- | --- | |

| Perceived Environment System |

Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup injunctive norms | --- | --- | |

| Social comparison | 1.07 [1.004,1.14]* | --- | |

| Situational triggers | 1.18 [0.94,1.47] | --- | |

| Protective Factors | --- | ||

| Committed relationship | --- | 0.69 [0.24,1.14]** | |

| Parental connectedness | --- | --- | |

| Parents married | 1.65 [0.93,2.96]+ | --- | |

|

| |||

| R 2 | .38 [.26,.49]*** | -- | |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; B = regression estimate; Freq. = frequency of; Attend. = attendance; GPA = grade point average. Two-part modeling looked at the probability of experiencing any oral sex hookup and the number of oral sex hookups given at least one occurred. All predictors were entered into the regressions; regression weights for highly non-significant predictors (T > 1) were fixed at zero to stabilize estimates. All remaining coefficients are reported. Significant predictors appear in boldface type.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

For those reporting at least one oral sex hookup.

We next examined predictors of the number of hookups involving receiving oral sex for women engaging in at least one hookup (Table 4). In the personality system, women who were higher in impulsivity engaged in more hookups involving receiving oral sex. Additionally, contrary to our hypothesis, women with higher levels of depression engaged in fewer hookups involving receiving oral sex. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college hookups involving receiving oral sex and who binge drank more frequently engaged in more hookups involving receiving oral sex. In contrast, women who attended religious services more frequently engaged in fewer hookups involving receiving oral sex. In the perceived environment system, contrary to our hypothesis, women who reported being in a committed relationship at the beginning of the school year engaged in more hookups involving receiving oral sex. Additionally, Asian women engaged in fewer hookups involving receiving oral sex.

Predictors of Hookups Involving Vaginal Sex

Finally, we explored risk and protective factors predicting vaginal sex hookups (Table 5); these findings were consistent with our hypotheses unless otherwise noted. We first examined predictors of engaging in any vaginal sex hookups during the academic year. In the personality system, women with stronger intentions to engage in vaginal sex hookups at baseline were more likely to hook up during the school year. In contrast, women reporting higher levels of subjective religiosity were less likely to engage in vaginal sex hookups. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college vaginal sex hookups and who used marijuana more frequently were more likely to engage in vaginal sex hookups. Finally, in the perceived environment system, women who reported more situational triggers were more likely to engage in vaginal sex hookups. Collectively, predictors explained 44% of the variance in engaging in vaginal sex hookups.

Table 5.

Predictors of Engagement in Hookups Involving inal Sex

| Any Hookups (Vaginal Sex) |

Number of Hookups (Vaginal Sex)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| OR [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | ||

| Demographics | Asian | --- | --- |

| Black | --- | --- | |

| Latina | --- | −0.67 [−1.30,−0.04]* | |

| Socioeconomic status | --- | 0.08 [−0.05,0.20] | |

| Personality System | Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup attitudes | --- | --- | |

| Hookup intentions | 1.25 [1.04,1.51]* | --- | |

| Depression | --- | --- | |

| Impulsivity | --- | --- | |

| Sensation-seeking | --- | 0.05 [0.01,0.10]* | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Self-esteem | --- | --- | |

| Subjective religiosity | 0.63 [0.46,0.87]** | 0.23 [−0.01,0.47]+ | |

| Behavior System | Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-college hookups | 7.99 [4.41,14.48]*** | 0.66 [0.26,1.07]*** | |

| Freq. binge drinking | 1.06 [0.97,1.17] | --- | |

| Freq. marijuana use | 1.14 [1.04,1.24]** | 0.05 [0.004,0.09]* | |

| Cigarette smoking | --- | 0.35 [−0.09,0.80] | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Religious service attend. | --- | --- | |

| High school GPA | --- | −0.57 [−1.20,0.07]+ | |

| Perceived Environment System |

Risk Factors | ||

| Hookup injunctive norms | --- | --- | |

| Social comparison | 1.06 [0.99,1.13]+ | --- | |

| Situational triggers | 1.26 [1.02,1.55]* | --- | |

| Protective Factors | |||

| Committed relationship | --- | --- | |

| Parental connectedness | --- | --- | |

| Parents married | --- | −0.52 [−0.94,−0.11]* | |

|

| |||

| R 2 | .44 [.34,.54]*** | -- | |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; B = regression estimate; Freq. = frequency of; Attend. = attendance; GPA = grade point average. Two-part modeling looked at the probability of experiencing any vaginal sex hookup and the number of vaginal sex hookups given at least one occurred. All predictors were entered into the regressions; regression weights for highly non-significant predictors (T > 1) were fixed at zero to stabilize estimates. All remaining coefficients are reported. Significant predictors appear in boldface type.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

For those reporting at least one vaginal sex hookup.

We next examined predictors of the number of vaginal sex hookups for women engaging in at least one hookup (Table 5). In the personality system, women higher in sensation-seeking engaged in more vaginal sex hookups. In the behavior system, women who reported pre-college vaginal sex hookups and who used marijuana more frequently engaged in more vaginal sex hookups. In the perceived environment system, women whose parents were married engaged in fewer vaginal sex hookups. Also, Latina women engaged in fewer vaginal sex hookups.

DISCUSSION

Before coming to college, a minority of women in our sample reported performing oral sex (26%), receiving oral sex (21%), and having vaginal sex (21%) in the context of hookups. Taken together with previous research (e.g., Manning, Giordano, & Longmore, 2006), our findings confirmed that a substantial minority of young women engage in penetrative sex hookups as adolescents. Following the methodological precedent that assesses specific sexual behaviors during hookups (Fielder & Carey, 2010b), we found that, during the first year of college, 25% of college women performed oral sex during a hookup, 20% received oral sex during a hookup, and 25% had vaginal sex during a hookup. These rates were lower than in prior studies with past-year hookup prevalence rates of 52-70% (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Owen et al., 2010); however, these previous studies also included hookups limited to kissing and/or petting, which are more common than hookups involving penetrative sex (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Paul et al., 2000). The higher prevalence of performing compared to receiving oral sex corroborated prior findings that, compared to men, women were more likely to perform, and less likely to receive, oral sex during hookups (England & Thomas, 2006). Possible explanations for this imbalance may include men’s reluctance to perform oral sex, women’s hesitancy to receive oral sex because of self-consciousness about their bodies or genitals, beliefs that oral sex is too intimate for hookups, and feelings of guilt and concern their partner will not enjoy performing it (Backstrom, Armstrong, & Puentes, 2012).

We used PBT as a heuristic framework to identify and test possible risk and protective factors as predictors of sexual hookups among college women. Several individual-level factors from the personality system emerged as risk factors for sexual hookups. In line with our hypothesis and the centrality of behavioral intentions to most theories of health behavior (see Webb & Sheeran, 2006), intention to hook up was a consistent risk factor, increasing the odds of oral and vaginal sex hookups. Contrary to our hypothesis and previous research (Olmstead et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2010), attitudes toward hooking up did not predict hookups. Attitudes are thought to influence intentions, and it is possible that the predictive power of attitudes weakened once intentions were included.

Also contrary to our hypothesis, depression was not related to performing oral sex or vaginal sex hookups and was associated with a lower number of hookups involving receiving oral sex. This finding corroborated previous results in which emotional distress did not predict hookups (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). It is unclear why depression might be related to hookups involving receiving oral sex, but not performing oral sex or vaginal sex. Additional research is needed to determine if this is a spurious finding or if depression may be related to frequency of hookups involving receiving oral sex. Some research has suggested a negative association between depression and sexual behavior (Frohlich & Meston, 2002); perhaps depressed women are less socially engaged or are less interested in making romantic/sexual connections via hookups.

We also examined two personality traits that are often related to risky sexual behavior: impulsivity and sensation-seeking (Charnigo et al., 2012). The tendency to make spur of the moment decisions and to seek novel or exciting experiences were both hypothesized to be risk factors for hooking up. In our sample, among women who hooked up, women higher in impulsivity reported a greater number of hookups involving receiving oral sex, and women higher in sensation-seeking reported a greater number of hookups involving vaginal sex. Given inconsistent findings (cf. Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013), additional research is needed to clarify the role of impulsivity and sensation-seeking in promoting hookup behavior.

Self-esteem was not related to receiving oral sex or having vaginal sex during hookups, but, among women who performed oral sex during hookups, higher self-esteem predicted a lower number of hookups. It is possible that high self-esteem may empower women to avoid performing oral sex during hookups if they do not enjoy it. The relationship between self-esteem and hooking up may be moderated by gender; however, Paul et al. (2000) found that self-esteem was negatively correlated with hooking up among both men and women. It may also be that self-esteem is not as influential on youth’s sexual behavior as once believed (Goodson, Buhi, & Dunsmore, 2006). Subjective religiosity was a consistent protective factor, reducing the odds of oral and vaginal sex hookups. Religiosity is believed to protect against involvement in problem behaviors by fostering moral beliefs and conventional attitudes (Donovan, 2005).

The strongest risk factor for engaging in all three types of hookups as well as the frequency of hookups was pre-college hookup behavior, corroborating previous research (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2011). This association suggests a behavioral tendency; early hookup experiences may provide a personal model for future behavior or may be related to future behavior through attitudes, norms, and intentions (Ouellette & Wood, 1998). These findings suggest that women’s hookup behavior during the first year of college will likely influence their hookup behavior later in college. Therefore, the transition to college is an important time for health care professionals to provide sexual health information and resources to help women make informed decisions. Of note from a research perspective, the magnitude of the effects of pre-college hookup behavior was considerably higher than all other predictors. Thus, in future research, it is important to control for previous behavior to identify factors that influence hooking up beyond this strong predictor. Binge drinking was predictive of increased odds of engagement in hookups involving performing oral sex and a greater number of hookups involving receiving oral sex, but was not predictive of vaginal sex hookups. Alcohol use likely increases contextual vulnerability for hookups by lowering inhibitions or providing a motive or “excuse” (Vander Ven & Beck, 2009).

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine marijuana use as a predictor of hooking up. In the context of assessing multiple forms of substance use, one might expect a diminution of predictive power for individual predictors. However, marijuana use predicted increased odds and a greater number of vaginal sex hookups; it also predicted hookups involving performing and receiving oral sex. Marijuana users tend to be less conventional (Kandel, 1984). Moreover, marijuana use has been associated with risky sexual behavior, perhaps by impairing judgment and reducing inhibitions (e.g., Anderson & Stein, 2011). Contrary to our hypothesis, cigarette smoking was not related to hookup behavior except for performing oral sex during hookups; smokers had a lower likelihood of engaging in hookups involving performing oral sex. Smoking was relatively infrequent in our sample (10%), which may be due in part to a legal age for purchasing cigarettes of 19 in the county in which the university is located; 94% of participants were 18 years old at baseline. Regardless of the cause, this lowered base rate restricted the range; without variation, co-variation is limited. In our sample, marijuana use was more prevalent than cigarette smoking (data not shown), so marijuana use may have subsumed the variance for smoking behaviors. Moreover, unlike marijuana use, tobacco use is legal and may be considered a more conventional behavior compared to marijuana use.

Religious service attendance and academic achievement, both hypothesized to engender conventional values and social control (Donovan, 2005), did not emerge as protective behavioral factors. The only exception was that, among women who engaged in hookups involving receiving oral sex, more frequent religious service attendance predicted a lower number of hookups. This single finding for religious service attendance contrasts with the more consistent protective effect of subjective religiosity. Religious service attendance was measured at baseline, so participants likely responded to this item based on their pre-college pattern of attendance, which may have depended on family or parental preferences; thus, subjective religiosity may have a stronger influence than religious service attendance. Moreover, students living in a new location may not yet have established a new place of worship or “religious home,” and academic and social demands may also keep college students from attending religious services. For these reasons, we might expect subjective religiosity to be more closely related to behavior during the first year of college compared to religious service attendance. Academic achievement may be too distal compared to other, more proximal, influences on hookup behavior. Qualitative research has suggested that women may view hookups as a convenient alternative to committed relationships, which are often perceived to be time-consuming to the point of potentially interfering with school (Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009). Future research should continue to explore the association between academic involvement and hooking up.

Lastly, we found evidence for risk and protective factors in the perceived environment system. Social comparison orientation was predictive of engaging in hookups involving performing and receiving oral sex. Women with a stronger tendency to compare themselves to others may be more apt to hook up to comply with perceived social norms about hooking up, which are consistently exaggerated (Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lambert et al., 2003). However, contrary to expectations, injunctive norms did not predict any of the three hookup outcomes. Only two other studies have examined social norms in relation to hooking up, and findings were inconsistent (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Fielder & Carey, 2010a). Given associations between social norms and other sexual behavior (Lewis et al., 2007), researchers should continue to explore both descriptive and injunctive norms with respect to hooking up. Consistent with a previous longitudinal study (Fielder & Carey, 2010a), we also found that having higher situational triggers for hookups predicted increased odds of engaging in hookups involving performing oral sex and vaginal sex. Situational factors provide both models and external triggers for risk behaviors.

In contrast to our expectations, being in a committed relationship at baseline was not protective against oral or vaginal sex hookups; however, among women who engaged in hookups involving receiving oral sex, those who were in a relationship at baseline reported a higher number of hookups. Women with more relationship experience may be more willing to ask for oral sex during hookups due to increased comfort with receiving oral sex (Backstrom et al., 2012). Lastly, among women who engaged in hookups involving performing oral sex and vaginal sex, women whose parents were married reported fewer hookups. Having married parents may provide a model of more conventional relationships and sexual behavior. This finding contrasts with prior research finding no link between parental marital status and hookup behavior (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2010).

To summarize, predictors of sexual hookups emerged from all three major domains within PBT. In the personality system, intentions to hook up were a consistent risk factor for sexual hookups during the first year of college, whereas subjective religiosity was a protective factor against all three types of hookups. In the behavior system, pre-college hookup behavior and marijuana use were risk factors for all three types of hookups. In the perceived environment system, social comparison orientation and situational triggers were risk factors, and having married parents was a protective factor. Taken together, our findings suggest a complex combination of influences on college women’s hookup behavior. Personality, previous behavior, substance use, social factors, and family of origin all combined to affect women’s relationship and sexual behavior choices. Pre-college hookup behavior was the only variable that predicted both the occurrence and number of hookups involving all three sexual behaviors assessed.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of this study suggest directions for future research. First, we sampled first-year women from a single university, which may limit the generalizability of our results. Future studies should include males, students in high school and other years in college, and non-college attending emerging adults. Second, we included only a subset of possible predictors of hookups. Future research should examine other personality traits that are correlated with hookups, such as making thoughtful relationship decisions (Olmstead et al., 2012; Owen & Fincham, 2011), attachment style (Paul et al., 2000), and extraversion (Gute & Eshbaugh, 2008). There was no consistent pattern with respect to race/ethnicity and hookups, but prior research suggests White students may be more likely than ethnic minority students to hook up (Owen et al., 2010). In addition to individual-level factors, we recommend exploring further the social influences of the family of origin, the peer network, and the college campus culture. Third, we did not assess whether hookups were with the same or different partners; the latter has implications for various health (e.g., STDs) and emotional (e.g., depression, self-esteem) consequences. Future research should use more fine-grained assessments of partner continuity and overlap. Lastly, we used PBT, which is not a sexuality-specific theory, to guide this research. Future research might draw upon theories of social exchange, courtship, relationship formation, and romantic love to increase our understanding of hooking up (e.g., Baumeister & Vohs, 2004; Moss, Apolonio, & Jensen, 1971; Sternberg, 1986). Despite these limitations, confidence in our results was bolstered by our study’s methodological and conceptual strengths, including using a prospective design with monthly surveys, having a large sample and high response rate, following women during a key developmental transition, using an established conceptual framework, testing a variety of predictors, and using sophisticated two-part modeling.

Health Education and Research Implications

Relationship and sexual exploration is developmentally appropriate for emerging adults (Tolman & McClelland, 2011), and hookups have become a popular way to initiate this exploration. The prevalence of hookups as well as empirical research suggests that hookups can have positive consequences (Bachtel, 2013; Owen & Fincham, 2011; Paul, 2006; Plante, 2006). However, hookups also increase health risk inasmuch as they often involve unprotected sex and sex while intoxicated or high; hookups can lead to sexual partner concurrency (or at least serial partners) and to sexual victimization (England & Thomas, 2006; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Flack et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012b). Given the relative dearth of research on negative health outcomes of hookups, as well as methodological limitations of the extant research (e.g., mostly qualitative and cross-sectional research designs), calls for interventions to prevent hooking up lack an empirical justification. Nevertheless, campus-based sexual education and health promotion efforts are warranted to minimize the harms that hookups involving risky behavior (e.g., unprotected sex, sex while intoxicated) might cause, to allow students to make informed decisions about their sexual behavior, and to promote safer sex during sexual hookups. The findings from this study suggest avenues that may be most fruitful.

For example, given the importance of alcohol and marijuana use as risk factors for hookups, students may benefit from education and interactive discussion about the association between substance use and hookups. Substance use before sex undermines safer sex with casual partners (Kiene, Barta, Tennen, & Armeli, 2009) and can lead to sexual coercion (Abbey, 2002). Notably, some event-level studies have found that condom use with casual partners is unrelated to alcohol use (e.g., Leigh et al., 2008). Fortunately, women respond well to brief, motivation-based interventions designed to promote more responsible and less harmful alcohol use (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007), which can help reduce sexual risk as well as other health, social, and academic problems.

Our results also have implications for future research. We found evidence for risk and protective factors across the personality, behavior, and perceived environment systems. Taken together, hooking up during the first year of college is influenced by high school behavior, substance use patterns, personality, behavioral intentions, the social and situational context, and the family of origin. Therefore, it is important to consider this array of individual, social, and contextual factors when studying this behavior. Focusing on any one system of influences (e.g., personality or family of origin) fails to capture the complicated matrix of forces that influence emerging adults’ relationship decisions.

Future research should also investigate the short- and long-term consequences of hooking up so that young people, parents, health educators, and health care providers understand the positive and negative effects of this practice. Researchers should utilize prospective designs and clinically relevant outcomes (e.g., longer-term depression as well as acute psychological distress) to allow for stronger inferences to be drawn compared to cross-sectional and qualitative studies. Lastly, there remains a need to integrate the collegiate hookup literature with the distinct, but related, larger literature on casual sex among heterosexuals and among gay males (see Garcia et al., 2012).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant R21-AA018257 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Michael P. Carey. The authors thank Annelise Sullivan for her assistance with data collection.

REFERENCES

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Suppl.):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–592. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BJ, Stein MD. A behavioral decision model testing the association of marijuana use and sexual risk in young adult women. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:875–884. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9694-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey JS, Smith SE. Development and validation of the Endorsement of the Hookup Culture Index. Journal of Sex Research. 2011 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637246. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.637246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtel MK. Do hookups hurt? Exploring college students’ experiences and perceptions. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013;58:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backstrom L, Armstrong EA, Puentes J. Women’s negotiation of cunnilingus in college hookups and relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:1–12. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.585523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriger M, Vélez-Blasini CJ. Descriptive and injunctive social norm overestimation in hooking up and their role as predictors of hook-up activity in a college student sample. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:84–94. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.607928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Sexual economics: Sex as female resource for social exchange in heterosexual interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:339–363. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogle KA. Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Kahn AS, Saville BK. To hook up or date: Which gender benefits? Sex Roles. 2010;62:661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Brimeyer TM, Smith WL. Religion, race, social class, and gender differences in dating and hooking up among college students. Sociological Spectrum. 2012;32:462–473. [Google Scholar]

- Burdette AM, Ellison CG, Hill TD, Glenn ND. “Hooking up” at college: Does religion make a difference? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48:535–551. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnigo R, Noar SM, Garnett C, Crosby R, Palmgreen P, Zimmerman RS. Sensation seeking and impulsivity: Combined associations with risky sexual behavior in a large sample of young adults. Journal of Sex Research. 2012 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.652264. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.652264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Shapiro CM, Powers AM. Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1528–1558. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin MS. College student involvement in cigarette smoking: The role of psychosocial and behavioral protection and risk. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2007;9:213–224. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Problem behavior theory. In: Fisher CB, Lerner RM, editors. Encyclopedia of applied developmental science. Vol. 2. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 872–877. [Google Scholar]

- Downing-Matibag TM, Geisinger B. Hooking up and sexual risk taking among college students: A health belief model perspective. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:1196–1209. doi: 10.1177/1049732309344206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour MC. What is moderate drinking: Defining “drinks” and drinking levels. Alcohol Research and Health. 1999;23:5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P, Thomas RJ. The decline of the date and the rise of the college hook up. In: Skolnick AS, Skolnick JH, editors. Family in transition. 14th ed Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2006. pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Calzo JP, Smiler AP, Ward LM. “Anything from making out to having sex”: Men’s negotiations of hooking up and friends with benefits scripts. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:414–424. doi: 10.1080/00224490902775801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh EM, Gute G. Hookups and sexual regret among college women. Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;148:77–89. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.1.77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group . Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Fetzer Institute; Kalamazoo, MI: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Are hookups replacing romantic relationships? A longitudinal study of first-year female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Predictors and consequences of sexual “hookups” among college students: A short-term prospective study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010a;39:1105–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual hookups among first-semester female college students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2010b;36:346–359. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2010.488118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Daubman KA, Caron ML, Asadorian JA, D’Aureli NR, Gigliotti SN, Stine ER. Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students: Hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:139–157. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich P, Meston C. Sexual functioning and self-reported depressive symptoms among college women. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:321–325. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]