Abstract

Objectives

Tuberculosis (TB) control in schools is a concern in low-income and middle-income countries with high TB burdens. TB knowledge is recognised as important for TB control in China, which has one of the highest TB prevalence in the world. Accordingly, National TB Control Guideline in China emphasised TB-health education in schools as one of the core strategies for improving TB knowledge among the population. It was important to assess the level of TB knowledge in schools following 5-year implementation of the guideline, to determine whether the information was reaching the targets.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Methods and study setting

This survey assessed TB knowledge and access to TB-health information by questionnaire survey with 1486 undergraduates from two medical universities in Southwest China.

Results

Overall, the students had inadequate TB knowledge. Only 24.1%, 27.2% and 34.1% of the students had knowledge of TB symptoms of cough/blood-tinged sputum, their local TB dispensaries and free TB treatment policy, respectively. Very few (14.5%) had heard about the Directly Observed Therapy Short Course (DOTS), and only about half (54%) had ever accessed TB-health education information. Exposure to health education messages was significantly associated with increased knowledge of the five core TB knowledge as follows: classic TB symptoms of cough/blood-tinged sputum (OR (95% CI) 0.5(0.4 to 0.7)), TB modes of transmission (OR (95% CI) 0.4(0.3 to 0.5)), curability of TB (OR (95% CI) 0.6(0.5 to 0.7)), location and services provided by TB local dispensaries (OR (95% CI) 0.6(0.5 to 0.8)) and the national free TB treatment policy (OR (95% CI) 0.7(0.5 to 0.8)).

Conclusions

The findings pose the question of whether it is time for a rethink of the current national and global approach to TB-health education/promotion which favours promotion of awareness on World TB Days rather than regular community sensitisation efforts.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The establishment of a baseline level of TB knowledge among undergraduate medical students. This is the first study to assess school-based TB health education/promotion in the study setting.

The main limitation is that the study used a cross-sectional design, which did assess TB knowledge changes before and after school TB health education/promotion.

The results disclosed that undergraduate medical students had inadequate TB knowledge. This calls for a rethink of current national and global approaches to TB health education/promotion.

Introduction

The 16th Global Report on Tuberculosis (TB) published by WHO in 2012 showed that the Millennium Development Goal target for halting and reversing the TB epidemic by 2015 had already been achieved, with mortality and incidence rates falling in 22 high-burden countries. Nevertheless, the global burden of TB remains untenable,1 in high-burden countries such as China. Globally, TB remains the second leading cause of death from infectious diseases (after HIV/AIDS).1 During the past 5 years, there has been a marked increase in the number of patients with TB diagnosed with multidrug resistant TB (MDR-TB) across the world.1 China has the world’s second largest TB epidemic and has contributed significantly to this MDR-TB increase. In recent years, the country has undertaken measures to control TB, and to evaluate the progress of TB control in the past decade, the country launched the 5th National Sampling Survey of TB Epidemiology in 2010.2 Results of the survey showed an estimated 8.28 million cases of pulmonary TB (PTB) from 2001 to 2010.2 Despite concerted international and national efforts to address TB in the country, annual prevalence (per 100 000 people) declined only minimally from 466 in 2000 to 459 in 2010.2 Similarly, incidence of MDR-TB among PTB cases has remained unchanged in the past decade, and resistance to first-line drugs among newly diagnosed patients with TB rose from 34.2% in 2007/20083 to 36.9% in 2010.2

Owing to the lack of knowledge of TB, only less than half the patients with TB symptoms seek healthcare timely.2 Available evidence shows that only 59% patients with TB comply with treatment, and among the public, only 57% have proper TB knowledge.2 Limited knowledge about signs and symptoms of TB often results in delays in TB diagnosis and treatment,4 which in return, increases not only the risk of TB transmission, but also the development of MDR-TB. China's MDR-TB prevalence rate of 6.8% is the highest in the world.2

TB control among undergraduate students is recognised as a concern in low-income and middle-income countries with high TB burdens. Undergraduate students usually live in relatively overcrowded conditions that are conducive to TB outbreaks.5 TB outbreaks among students have been reported even in such low-burden countries as the UK, Italy, Ireland and the USA.6–10 Chinese undergraduate students are recognised as a particularly vulnerable population for TB. TB prevalence (per 100 000) among Chinese students has been reported to be as high as 1520 which is significantly higher than the prevalence (459) for the general population.11 Chongqing, Guizhou and Shanxi provinces were the three provinces with the highest TB burden among undergraduate students between 2005 and 2008.12 In addition, several TB outbreaks among undergraduate students were recently reported in Chongqing, Liaoning, Zhejiang, Shandong and Guizhou, with the incidence rates ranging from 620 to 31 370/100 000.11–17

Medical students in universities can be exposed to TB infection during clinic rotations.18 Thus, adequate knowledge of TB epidemiology and control is critically important for this population. Knowledge of TB among medical undergraduates in university is also important since they represent potential future physicians or leaders in the fight against TB.19 In 1997, WHO released a report following a workshop on Tuberculosis Control and Medical Schools held in Rome, Italy, which stressed the importance of equipping graduating medical students with proper knowledge and skills related to effective TB control.20 WHO later released a manual that aims to inform medical students and medical practitioners about best practices in managing patients with TB.21 Several studies have documented inadequate TB knowledge and poor compliance with TB treatment guidelines among practicing physicians.22–24 In countries where TB (including MDR-TB) presents significant challenges to public health, equipping emerging physicians with in-depth TB knowledge is of critical importance in the overall efforts to reduce the burden of the disease. In China, TB-health promotion in schools was emphasised in the 2008 National Guideline for TB Control.25 It was important to assess the level of TB knowledge in schools following 5-year implementation of the guideline. This survey assessed TB knowledge and access to TB-health information among 1486 preclinical undergraduate students from two medical universities in Southwest China, which has one of the highest TB burdens in the country. It was hoped that the findings could help to identify whether the information was reaching the targets, and thus engender efforts to strengthen TB school education in the region and similar locales in low-income and middle-income countries with high TB burden.

Methods

Study setting

The study setting, Southwest China, includes Chongqing Municipality, the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou and Tibet Autonomous Region (figure 1) where prevalence rates (cases/100 000) of active TB (695), smear-positive TB (105) and culture-positive TB (198) are much higher than the national prevalence rates of 459, 66 and 119, respectively.2 Southwest China has a population of more than 19 million which represent more than 10% of China's population of 1.3 billion people.

Figure 1.

The Southwestern People's Republic of China. Southwest China is demonstrated in this figure. The place marked with red colour is Southwest China which includes the municipality of Chongqing, the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Guizhou and the Tibet Autonomous Regions.

Participants

Southwest China has 10 medical universities offering 5-year majors in clinical medicine, public health, pharmacy, medical laboratory, Chinese medicine and nursing. We randomly selected 2 of the 10 universities and restricted our sample frame to preclinical students (students who have not received clinic curriculum) in their first to third year of training. We excluded fourth-year and fifth-year students as they might have already obtained TB knowledge from their clinical training as part of their clinical curriculum rather than from government school TB health education. The survey was conducted between November 2011 and May 2012 and focused on the assessment of TB knowledge among the respondents. The sample frame consisted of 20 000 eligible students. To obtain a power of 80% and a confidence level of 95%, we calculated the study sample to be 1536.26 During recruitment, potential participants were approached and provided with detailed explanation of the study and its objectives. They were then asked if they would be interested in volunteering to participate. Those who expressed interest were asked to read the informed consent form, and were assured of confidentiality. They were then asked to sign the informed consent form as a conformation of their voluntary participation in the study. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the College of Preventive Medicine, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China (20 October 2011) and the School of Nursing, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (28 April 2012).

Questionnaire

The survey was cross-sectional in design. Following participant enrolment in the study, data were collected by self-administered questionnaire that assessed participants’ knowledge about TB signs/symptoms, transmission, management and control. Data were elicited on the following variables: sociodemographic profile (age and sex), degree major (clinical and non-clinical), year in the medical programme, TB knowledge (symptoms, mode of transmission, treatment, knowledge of TB control facilities in the study setting, local TB control policies and programme) and core knowledge of TB, namely, five core TB knowledge areas which include the following: (1) classic TB symptoms of cough/blood-tinged sputum, (2) TB modes of transmission, (3) curability of TB, (5) location and services provided by TB local dispensaries and (5) the national-free TB treatment policy.

Data analysis

Epi-data V.6.0 was used for data entry. Data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences V.18.0. To assess TB knowledge among the participants, we calculated the percentage of people who provided correct response to questions about the six symptoms of TB, three ways of transmitting TB, five items related to TB treatment and five core knowledge of TB. We used χ2 statistics to assess participants’ responses by gender, year in medical school and degree major. A binary logistic regression model which included variables with statistical significance on the χ2 test, were used to examine factors associated with core knowledge of TB among the respondents. We used a two-tailed probability level of <0.05 as the level of statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

A total of 1486 undergraduate medical students participated in the survey. Of these, 617 were in their first-year medical training, 399 in the second year and 470 in the third year. A majority of the respondents (74.2%; n=1102) were men, and 68.4% students were majoring in clinical medicine. Only 54% of the students indicated having access to some kind of TB health information (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of undergraduates surveyed in medical universities in Southwest China (n=1486)

| Demographic factors | N | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1102 | 74.2 |

| Female | 384 | 25.8 |

| Grade | ||

| Year 1 | 617 | 41.5 |

| Year 2 | 399 | 26.9 |

| Year 3 | 470 | 31.6 |

| Major | ||

| Clinic medicine | 1017 | 68.4 |

| Non-clinic medicine | 469 | 31.6 |

| Access to TB health education | ||

| Yes | 802 | 54 |

| No | 684 | 45 |

TB, tuberculosis.

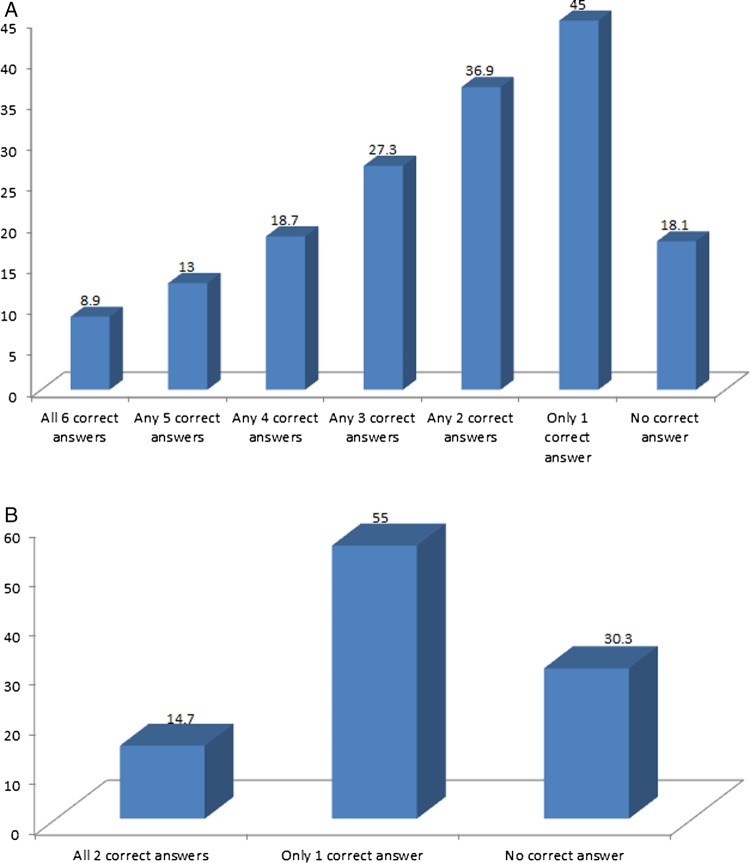

Knowledge of TB symptoms

The respondents’ knowledge of symptoms is shown in table 2. About 18% (n=261) had no knowledge of any TB symptoms, and less than 10% (n=132) were able to identify all TB symptoms (figure 2A). As for overall knowledge of TB symptoms, 10.8% (n=119) of men and 3.4% (n=13) of women had knowledge of all of the classic symptoms of TB (p≤0.05). Slightly more than 13% (13.6%; n=84) of students in the third year of medical school, 4.3% (n=17) of those in the second year and 6.6% (n=31) of first-year students had knowledge of all of the classic symptoms (p≤0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in knowledge of TB symptoms between students in clinical and non-clinical degree majors (p>0.05; table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge of TB signs/symptoms, transmission and treatment among undergraduates in medical universities in Southwest China†

| Sex n (%) |

Grade n (%) |

Major n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of TB | Total n (%) | Male | Female | Year 3 | Year 2 | Year 1 | Clinical medicine | Non-clinical medicine |

| Students had knowledge of TB signs/symptoms | ||||||||

| Chronic cough | 597 (40.2) | 501 (45.5) | 96 (25.0)* | 262 (42.5) | 118 (29.6) | 217 (46.0)* | 399 (39.2) | 198 (42.2) |

| Haemoptysis | 756 (50.9) | 608 (55.2) | 148 (38.5)* | 332 (53.8) | 176 (44.2) | 248 (52.9)* | 509 (50.0) | 247 (52.8) |

| Fever | 371 (25.0) | 298 (27.1) | 73 (19.0)* | 204 (33.1) | 73 (18.4) | 94 (20.0)* | 269 (26.5) | 102 (21.7) |

| Night sweats | 328 (22.1) | 265 (24.1) | 63 (16.4)* | 209 (33.9) | 54 (13.6) | 65 (13.8)* | 235 (23.1) | 93 (19.8) |

| Weakness | 398 (26.8) | 348 (31.6) | 50 (13.0)* | 212 (34.4) | 73 (18.3) | 113 (24.0)* | 270 (26.5) | 128 (27.3) |

| Weight loss | 318 (21.4) | 286 (26.0) | 32 (8.3)* | 190 (30.8) | 43 (10.8) | 85 (18.1)* | 220 (21.7) | 98 (20.9) |

| All above TB signs/symptoms | 132 (8.9) | 119 (10.8) | 13 (3.4) * | 84 (13.6) | 17 (4.3) | 31 (6.6) * | 88 (8.7) | 44 (9.4) |

| Students had knowledge of TB transmission | ||||||||

| TB is an infectious disease | 1231 (82.8) | 893 (81.0) | 338 (88.0)* | 531 (86.1) | 316 (79.4) | 384 (81.5)* | 854 (84.0) | 377 (80.4) |

| Transmitted by cough | 414 (27.9) | 338 (30.7) | 76 (19.8)* | 186 (30.1) | 92 (23.1) | 136 (29.0) | 293 (28.8) | 121 (25.8) |

| Transmitted by sneezing and talking loudly | 841 (56.6) | 607 (55.1) | 234 (60.9)* | 386 (62.6) | 191 (48.0) | 264 (56.3)* | 597 (58.8) | 244 (52.0)* |

| Students had knowledge of TB treatment | ||||||||

| TB is a treatable disease | 1183 (79.6) | 891 (81.0) | 292 (76.0)* | 477 (77.3) | 318 (80.1) | 388 (82.6)* | 802 (79.0) | 381 (81.4) |

| Duration of treatment | 439 (29.5) | 313 (28.5) | 126 (32.8)* | 207 (33.5) | 109 (27.5) | 123 (26.2)* | 304 (30.0) | 135 (28.8) |

| Aware of TB dispensary | 404 (27.2) | 267 (24.4) | 137 (35.7)* | 169 (27.4) | 108 (27.1) | 127 (27.0) | 270 (26.5) | 134 (28.6) |

| Aware of free treatment policy | 506 (34.1) | 345 (31.4) | 161 (41.9)* | 197 (31.9) | 123 (31.1) | 186 (39.5)* | 356 (35.1) | 150 (32.0) |

| Aware of DOTS | 215 (14.5) | 142 (12.9) | 73 (19.0)* | 110 (17.8) | 55 (13.9) | 50 (10.8)* | 148 (14.6) | 67 (14.3) |

*p<0.05.

†χ2 Test used to compare between men and women, different grades and different majors.

DOTS, Directly Observed Therapy Short Course; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 2 .

Knowledge of tuberculosis (TB) symptoms and transmission among undergraduate medical students in Southwest China. (A) Presents the percentage of undergraduate medical students with who correctly identified the classic symptoms of TB. (B) Presents the percentage of undergraduate medical students who correctly identified means of TB transmission.

Knowledge about TB transmission

Only 27.9% (n=414) of the respondents were aware that TB could be transmitted through exposure to droplet nuclei from the cough of an infected person (table 2), and only 14.7% (n=218) knew the two main routes of TB transmission (figure 2B). Overall, more women (88%; n=338) and third-year students (86.1%; n=531) knew the transmission routes of TB (p<0.05).

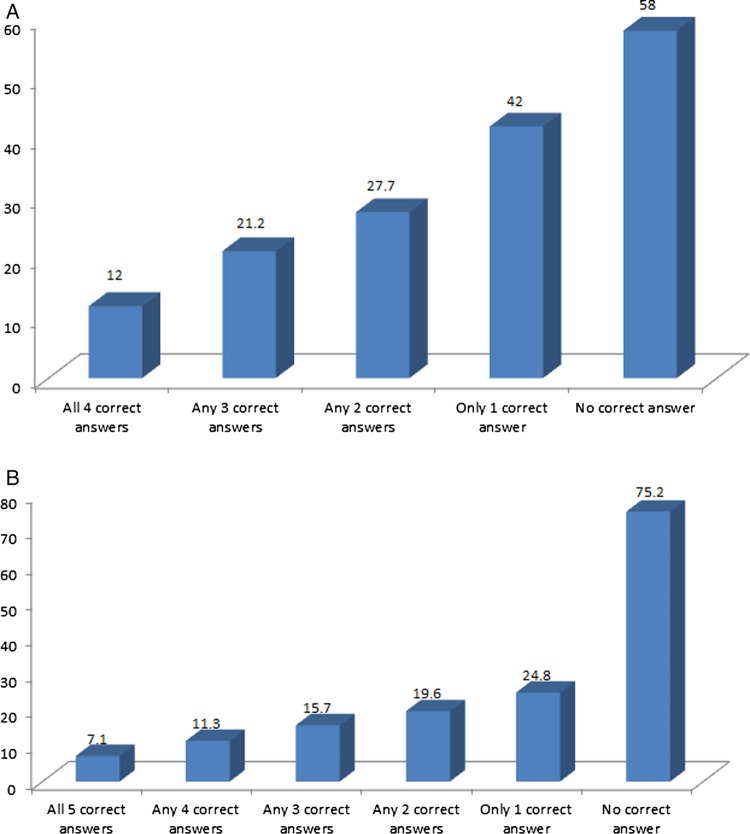

Knowledge about TB treatment and policies

Although 80% of the students knew that TB was curable, only 30% (n=446) knew the duration of TB treatment. Only 27.2% (n=404) knew TB control facilities (TB dispensaries); 34% and 14.5% had heard of the national-free TB treatment policy and Directly Observed Therapy Short Course (DOTS), respectively (table 2). A greater proportion of female than male respondents had better knowledge about the duration of TB treatment, TB control facilities, free TB treatment policy and DOTS (p≤0.05). Overall, third-year students had better knowledge of TB treatment except for knowledge on TB as a curable disease and free treatment policy. There were no significant differences between students in clinical and non-clinical majors (table 2). Only 12% (n=178) of the respondents knew all the four items included in the free TB treatment policy (registration, sputum test, chest x-rays and anti-TB drugs; figure 3A). Less than 10% (n=106) of the students were familiar with all five items of DOTS (figure 3B).

Figure 3 .

Knowledge of tuberculosis (TB)-free policy and Directly Observed Therapy-Short Course (DOTS) among undergraduate medical students in Southwest China. (A) Presents the percentage of undergraduate medical students with who have knowledge of the free TB treatment policy in China; (B) presents the percentage of undergraduate medical students correctly identified the contents of the Directly Observed Therapy-Short Course (DOTS) programme.

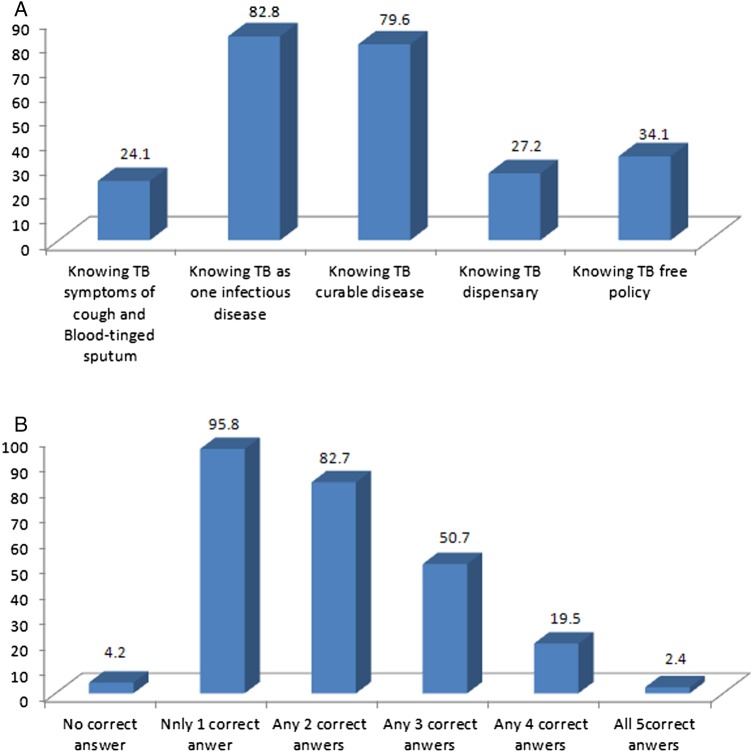

Core knowledge of TB

With regard to core knowledge of TB, less than half students had knowledge of TB symptoms of cough/blood-tinged sputum, their local TB dispensaries and the national free TB treatment policy (figure 4A). Only 2.4% were familiar with all five core TB knowledge areas (figure 4B). Multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that access to health education was associated with the five core TB knowledge: (OR (95% CI) 0.5(0.4 to 0.7)) for classic TB symptoms of cough/blood-tinged sputum; (OR (95%CI) 0.4(0.3 to 0.5)) for means of TB transmission; (OR (95% CI) 0.6(0.5 to 0.7)) for curability of TB; (OR (95% CI) 0.6(0.5 to 0.8)) for TB dispensaries and (OR (95% CI) 0.7(0.5 to 0.8)) for the national-free TB treatment policy. Men had poor knowledge related to transmission of TB, TB dispensaries and free TB treatment policy (OR (95% CI) 1.8(1.3 to 2.7), 1.7(1.3 to 2.4), 1.9(1.5 to 2.4)), respectively. Third-year students had better knowledge of TB compared with students in the first and second years (table 3).

Figure 4 .

Knowledge of core tuberculosis (TB) knowledge among undergraduate medical students in Southwest China. (A) Presents the percentage of undergraduate medical students correctly answered each question for core TB knowledge and (B) percentage of undergraduate medical students correctly answered none, only one question, any two, any three, any four and any five questions for core TB knowledge. This figure presents undergraduate medical students’ knowledge of core TB symptoms.

Table 3.

Factors associated with the core knowledge of tuberculosis (TB) among undergraduates in medical university in Southwest China

| OR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | TB symptoms of cough and blood-tinged sputum | TB as one infectious disease | TB as one curable disease | TB dispensary | TB-free policy |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.7) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.4) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.4) |

| Grade | |||||

| Year 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Year 2 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.7 (1.5, 1.9) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.0) |

| Year 3 | 1.8 (1.2,2.6) | 1.2 (0.8,1.7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) |

| Major | |||||

| Clinic medicine | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Non-clinic medicine | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.7 (0.5, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) |

| Access to TB-health education | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| No | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) |

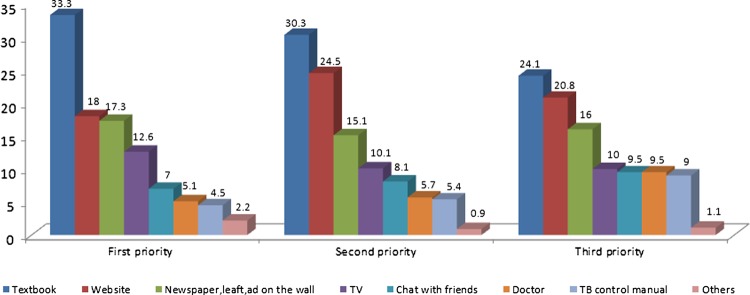

Sources of TB knowledge

With regard to how the respondents gained awareness and understanding of TB, survey results indicated that the most frequent source of information was textbooks, the second was the internet and the third was the media (newspaper and billboards; figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sources of tuberculosis (TB) knowledge among undergraduate medical students in Southwest China. This figure presents undergraduate medical students’ major sources of information on TB: the percentage of undergraduate medical students ranked the approach to get TB knowledge.

Discussion

TB is still one of the most important global public health threats. If global control of the disease does not improve, the annual global incidence is expected to increase from the current 21% to 61% by 2020.27 Early detection and adequate treatment are critical control measures. Despite the fact that China carries one of the highest TB burdens in the world, lack of knowledge about the disease remains an abiding problem in the country, and thus, presents a barrier to control efforts.2

Medical students are China's future health professionals and clinical leaders. Thus, understanding their level of awareness about TB is important. Unfortunately, this survey revealed that these students had generally poor knowledge of TB. Surveys conducted in other countries have reported inadequate knowledge of TB among medical professions students. In Turkey, for example,28 a study of 828 fourth-year medical students found that they lacked skills in interpreting radiology and smears even in their last year of medical school. One study in Brazil found that although medical students had had good knowledge of biosafety norms, they engaged in risky behaviours in healthcare settings where patients with TB were assisted29 Similarly, a study in the USA reported that, prior to implementation of the National Tuberculosis Curriculum Consortium (NTCC) in US medical schools, about one-third of medical students did not know the method for administering tuberculin skin test or that the BCG vaccine was not a contraindication for TB skin testing.30

The 2008 National Guideline for TB Control in China emphasises five items of core knowledge of TB.25 In the present study, it is of particular concern that the students scored very low in the TB core knowledge domain. The average knowledge base for all of the five core knowledge domains was only 2.4%, which was lower than the score (43.45%) reported in a previous study in China's Hunan province.31 We also found that only 24.1% knew the classic symptoms of TB (cough and blood stained sputum), which was similar to the report in Nanjing, China, where only 26.3% students were familiar with TB symptoms.32 This study observed that less than 30% of the respondents knew the course of TB treatment and were aware of TB control facilities in Southwest China which was lower than the rate observed in a previous study (36.66%).32 We found that only 30% knew the free TB treatment policy in China, which was similar to that reported in a related study.33 One-third of our respondents could not identify a mode of transmission for TB. A survey of final-year medical students in China's Hunan province in 2000 concluded that knowledge and practical competencies regarding TB among final-year medical students were generally inadequate.34 Results of our current study showed that the situation has not improved in the past 13 years.

TB education has been widely recognised as an effective way to promote TB knowledge among students. In 2003, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) perceived a need to strengthen the teaching of TB to health-profession students, and funded the NTCC to help address this need.30 Evidence shows that this has contributed to marked improvement in TB knowledge among students, nationally.30 35 36 Strong recommendations to strengthen TB knowledge of medical and other health-profession students through education have also been made by other countries.37 Although the National Guideline for TB Control in China emphasises TB health education and promotion for the public, patients with TB and students, TB health education and promotion in universities remain suboptimal.25 Findings from several studies have shown that 40–63.7% of students reported ‘hearing from others’ as their primary source of information about TB.32 37 This study also found that only 54% students had ever received TB health education. Accessing TB health education was significantly associated with core knowledge of TB. Given that non-clinical students have less opportunity to learn about TB as part of their regular curriculum, school TB health education should be seen as a primary source of information on TB for them.

Conclusion

In countries with high TB burden, it is important that all opportunities to raise population awareness about the disease are used to the optimum. In line with the WHO settings approach to health promotion,20 schools should be seen as important avenues for TB health education given the multiplier effect such intervention is likely to have on the students, their families, communities and others in their social networks.20 Unfortunately, there is the tendency to focus promotion of TB awareness on national/global TB Control Days to the neglect of a plethora of opportunities for ongoing promotion in diverse settings. The overall poor knowledge of TB among medical students demonstrated by this study supports the need to increase school TB health promotion, especially in the light of recent outbreaks of TB in universities in Southwest China.13 17 Given the high burden of TB in Southwest China, especially in rural provinces, TB health promotion in schools should be strengthened on an ongoing basis and in coordination with local TB control departments and district-level Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is a need for targeted efforts to educate students about TB since the students can be a major source of information to rural dwellers, including their own families and others in their circles of influence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YL designed this survey; JE guided the questionnaire design and data collection; YZ, DL and XL collected the data; DL managed the data; and YZ analysed the data. YZ and YL drafted the manuscript and JE edited the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results, revised the report and approved the final version.

Funding: The study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Award #: 81001297).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Boards of the College of Preventive Medicine, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China (20 October 2011) and the School of Nursing, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China (28 April 2012).

Ethics approval: The ethics committees of the two study universities approved the study protocol prior to its implementation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization 2012. Global Tuberculosis report. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf

- 2.Wang Y. Report of the fifth national sampling survey of TB epidemiology. Beijing: Military Medical Science Press, 2011:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y, Xu S, Wang L, et al. National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in China. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2161–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Ehiri J, Tang S, et al. Factors associated with patient, and diagnostic delays in Chinese TB patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2013;11:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbara V. Epidemiology in health care. 3rd edn Prentice Hall, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Lodi Tuberculosis Working Group A school- and community-based outbreak of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in northern Italy, 1992–3. Epidemiol Infect 1994;113:83–93 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridzon R, Kent JH, Valway S, et al. Outbreak of drug-resistant tuberculosis with second-generation transmission in a high school in California. J Pediatr 1997;131:863–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoge CW, Fisher L, Donnell HD, Jret al. Risk factors for transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a primary school outbreak: lack of racial difference in susceptibility to infection. Am J Epidemiol 1994;139:520–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quigley C. Investigation of tuberculosis in an adolescent. The Outbreak Control Team. Common Dis Rep CDR Rev 1997;7:R113–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shannon A, Kelly P, Lucey M, et al. Izoniazid resistant tuberculosis in a school outbreak: the protective effect of BCG. Eur Respir J 1991;4:778–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Pan JP, Zhang TH, et al. Survey on the knowledge, attitude and behaviors of TB among college students. Chin J Public Health 2006;22:661–2 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X, Chen W, Huang F. Analysis on TB of national report of students TB during 2004–2008. Chin Health Educ 2009;25:803–5 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou S, Chen M. Epidemiology survey on outbreaks of TB in the universities in Chongqing. Health Med Res Pract Higher Inst 2005;2:7–10 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi HY, Meng W, Liu DS. Epidemiology survey on outbreaks of TB in universities in Dandong city. Chin. J Health Lab Technol 2005;15:1377 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu M, Luo J, Lu M, et al. Epidemiology survey on outbreak of TB in university in Hangzhou city. J Med Res 2006;35:61–3 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu QQ, Ju YX, Li YY. Survey on outbreak of TB in university. Chin J Sch Health 2007;28:1147 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan MB, Yu YL, Zhang HW. Epidemiology survey on outbreak of TB in university in Guizhou province. Chin Mod Doct 2009;47:102–3 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva VM, Cunha AJ, Kritski AL. Tuberculin skin test conversion among medical students at a teaching hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23:591–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta D, Bassi R, Singh M, et al. To study the knowledge about tuberculosis management and national tuberculosis program among medical students and aspiring doctors in a high tubercular endemic country. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2012;5:206–8 [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Tuberculosis control and medical schools. Report of a WHO Workshop, Rome, Italy, 29–31 October 1997. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1998/WHO_TB_98.236.pdf

- 21.Nadia AK, Donald AE. Tuberculosis. A manual for medical students. World Health Organization, 2005, WHO/CDS/TB/99.272 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arif K, Ali SA, Amanullah S. Physician compliance with national tuberculosis treatment guidelines: a university hospital study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1997;2:2225–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LoBue PA, Moser K, Catanzaro A. Management of tuberculosis in San Diego County: a survey of physicians’ knowledge, attitudes and practices. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001;5:933–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan JA, Zahid S, Khan R, et al. Medical interns’ knowledge of TB in Pakistan. Trop Doct 2005;35:144–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Disease Control in China The operational guideline for tuberculosis control program in China. Beijing: Ministry of Health, 2008:101–5 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braden CR. Infectiousness of a university student with laryngeal and cavitary tuberculosis. Investigative team Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:565–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dye C, Garnett GP, Sleeman K, et al. Prospects for worldwide tuberculosis control under the WHODOTS strategy. Lancet 1998;352:1886–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilicaslan Z, Kiyan E, Erkan F, et al. Evaluation of undergraduate training on tuberculosis at Istanbul Medical School. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:159–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teixeira EG, Menzies D, Cunha AJ, et al. Knowledge and practices of medical students to prevent tuberculosis transmission in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2008;24:265–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson M, Harrity S, Hoffman H, et al. A survey of health-profession students for knowledge, attitudes, and confidence about tuberculosis, 2005. BMC Public Health 2007;7:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng SD, Yang SQ, Ling HY. Investigation on knowledge, attitude and behavior regarding tuberculosis in university students in Hengyan City. Chin J Sch Doct 2011;25:815–17 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Zhang XN, Cao SY, et al. Cognition of tuberculosis related knowledge and attitude among college students in Nanjing. Chin J Sch Health 2012;33:263–4 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan HY. Survey on the knowledge, attitude and behaviors related to TB among undergraduate students in universities. Chin J Sch Health 2009;30:639 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai LQ, Ziao SY, Xie HW, et al. Knowledge and practice regarding tuberculosis among final-year medical students in Hunan, China. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2003;26:458–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrity S, Jackson M, Hoffman H, et al. The National Tuberculosis Curriculum Consortium: a model of multi-disciplinary educational collaboration. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007;11: 270–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen PA. Where should infection control programs for tuberculosis begin? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu L, Tian M, Pan R, et al. Investigation on college student’ knowledge, confidence and behavior about prevention and treatment for tuberculosis in chengdu. Parasitoses Infect Dis 2008;6:185–7 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.