Abstract

Objective

Evaluating the effects of Tai Chi exercise on physical fitness, blood pressure, and perceived health in community-dwelling elderly.

Design

A randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Community-dwelling elderly in Vinh city, Vietnam.

Participants

Ninety-six community-dwelling participants aged 60 to 79 years (68.9 ± 5.1 years) were recruited.

Intervention

Subjects were divided randomly into two groups: Tai Chi and Control groups. Participants in the Tai Chi group (aged 69.02 ± 5.16 years) attended a 60-minute Tai Chi practice session twice a week for 6 months. The session consisted of a 15-minute warm-up and a 15-minute cool-down period. The Control group (aged 68.72 ± 4.94 years) maintained routine daily activities.

Outcome measures

The Senior Fitness Test and Short-Form 36® (SF-36®) are primary outcome measures.

Results

After 24 weeks of the Tai Chi training program, the intervention group showed significant decrease in systole of 12 mmHg and heart rate 6.46 bpm. Body mass index and waist–hip ratio were also reduced by 1.23 and 0.04, respectively. The Senior Fitness Test and SF-36 showed significant improvement.

Conclusion

In this randomized controlled trial study, Tai Chi is beneficial to improve systole blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index, waist–hip ratio, perceived health, and physical fitness. Assessment of the effects of Tai Chi may be focused more on chronic disease with a long-term training program in the future.

Keywords: physical fitness, health, Tai Chi

Introduction

Functional losses have been related to aging and these losses are also affected by physical inactivity.1 Moreover, an active lifestyle is important to prevent declines in functional capacity with age. The benefits of Tai Chi on physical function and health-related quality of life for elderly have been documented, such as improved balance, flexibility, and increased confidence in less-robust elderly,2 improved physical strength and reduced fall risk for fall-prone older adults,3 benefits of strengthened hamstrings and dynamic balance,4 a beneficial effect on physical functioning,5 and increased perceptions of self-efficacy.6

Tai Chi is widely practiced in China and Asia. It consists of a series of gentle physical activities with elements of meditation, body awareness, imagery, and attention to breathing.7 Furthermore, Tai Chi is a low-intensity exercise that has aerobic benefits,8 is effective for improving health fitness,9 and prevents decline in functional balance and gait.10 Tai Chi also appears to have physiological and psychological benefits and to be safe and effective in promoting balance control, flexibility, and cardiovascular fitness.11

By using the Short Form-36® (SF-36®) and exploring eight indicators related to quality of life,12 the specific problems of health-related quality of life can be identified. Therefore, the 36-item short-form questionnaire which was constructed to survey health status in the Medical Outcomes Study, was used. It was designed for use in clinical practice and research, health policy evaluations, and general population surveys. It is also a survey used to assess the change in multiple dimensions or scales of health status involving physical-, social-, and role-functioning, bodily pain, mental health, and health perception. Scores for each scale range from 1 to 100 with higher scores reflecting better health status. We also used the Senior Fitness Test (SFT) kit developed by Rikli and Jones which has become a standard tool for assessing physical fitness with older adults.13 This test protocol was designed to evaluate the physiological capability related to independently functioning: lower and upper body strength, aerobic endurance, lower and upper body flexibility and agility, and dynamic balance.

Many community-dwelling elderly people living in Vinh city engage in Tai Chi. However, there has been no comprehensive systematic study carried out on long-term physical function and perceived health as well as fall efficacy effects of Tai Chi in Vietnam. Our study was to investigate and examine the effects of Tai Chi on physical fitness, perceived health, blood pressure, and fall efficacy for the elderly. From these results, we may promote more people to engage in Tai Chi.

Methods

Participants

Ninety-six community-dwelling participants aged 60 to 79 years (68.9 ± 5.1 years) were recruited from Vinh city (urban area) to undertake a Tai Chi program. Six subjects (6.2%) dropped out within 3 months (first phase). Seventeen subjects (17.7%) dropped out after the next 3 months. A 6-month Tai Chi training program included pretraining, posttraining, and follow-up (follow-up was used only for Tai Chi group). Inclusion criteria for both groups included the subjects being able to perform the SFT fully, finish the Mini-Mental State Examination with a score greater than 24, and have no previous experience in Tai Chi. Exclusion criteria included subjects with serious disease such as: symptomatic coronary insufficiency, angina, arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, or dementia problems.

Intervention

A randomized, controlled trial: One hundred and two subjects were recruited. Six subjects did not the meet the exclusion criteria of the Mini-Mental State Examination (>24). Subjects were divided randomly into two groups: Tai Chi training group and Control group. The subjects were expected to consent and volunteer. Participants in Training group (n = 48, median (M) age = 69.2 years, standard deviation (SD) = 5.3) were assigned to 6 months of Tai Chi training. Participants in the control group (n = 48, mean age = 68.7, SD = 4.9) were instructed to maintain their routine daily activities and not to begin any new exercise programs. Based on the previous findings14,15 with the standardized mean difference of the group means, alpha level = 0.05, desired statistical power = 0.8, effect size (ES) is set at medium (0.5). Experienced Tai Chi instructors were selected by investigators to teach classes. Tai Chi is a 24-form exercise incorporating elements of balance, postural alignment, and concentration.

Participants in the Tai Chi group attended a 60-minute Tai Chi practice session twice a week for 6 months. The session consisted of a 15-minute warm-up and a 15-minute cool-down period. Participants in the Control group were instructed to maintain their routine daily activities and not to begin any new exercise programs.

Outcome measures and test protocol

Physical fitness and perceived health were the two main outcomes of this study assessed by utilizing the SFT13 and a short-form general health survey (SF-36).12

Senior Fitness Test

The SFT instrument includes seven items consisting of six domains of physical function: lower body strength, upper body strength, aerobic endurance, lower body flexibility, and upper body flexibility (as described by Rikli and Jones).13

Short Form-36

The SF-36 includes 36 items indicating eight domains of health related-quality of life: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health (as described by Ware and Sherbourne).12

Blood pressure measurement protocol

Blood pressure was measured while the subject is seated comfortably. The arm being used should be relaxed, uncovered, and supported at the level of the heart. Only the part of the arm where the blood pressure cuff is fastened needs to be at heart level, not the entire arm. An adjustable cuff-sided sphygmomanometer was used for arm circumference 27 to 34 cm, ‘adult’ cuff 16 × 30 cm. Subjects were measured at least two times within one test-period, before exercise and at least 1 hour after exercise. Having measured the participant before exercise, they were given 10 minutes to adjust to the temperature of the testing room. Subjects were told and encouraged to be relaxed before being tested. Measurements were taken by the same colleagues and physicians expert in blood pressure measurement methods and procedures.

Instrumentation

The instrumentation for this study included: a folding chair; stopwatches with 1/10 second reading (Hanhart profile J.W. German); hand-weights were dumbbells: 5 Ibs (2.27 kg) for women and 8 Ibs (3.63 kg) for men (weight-changeable dumbbells, German); scale (China); masking tapes (Vietnam); long tape measures (Butterfly, Shanghai, China); cones (or similar markers); small pencils; sphygmomanometer; SF-36 sheets; and SFT score cards.

Statistical analyses

An independent samples t-test was performed to analyze the differences between two groups. Bland–Altman plot (mean and difference) was used for comparisons of pre-post-training within group. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the differences in test phases. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Before applying the t-test, however, the normal distribution of the data was controlled.

Results

The descriptive characteristics of the samples in both Tai Chi and Control groups are shown in Table 1. The average age of participants is 68.98 years (SD 5.11), average BMI 24.28, and average WHR 0.94 cm. The sexes of ninety-six participants were split equally between female and male. Their marital status is as follows: living with other, n = 24 (25%); married, 53 (55.2%); widowed, 13 (13.5%); single, 1 (1.0%); and no response, 5 (5.2%). The participants; education level is as follows: range 5–9 years, n = 25 (25%); 10–12 years, 45 (49.6%); and over 12 years, 27 (28.1%). The number of participants in Tai Chi and Control groups at baseline is equal, and the ratio of males and females in both groups were also equally distributed randomly. The average age of Tai Chi and Control groups is 69.23 and 68.73 years, respectively. In the Tai Chi group, the average height is 1.58 m, average weight is 60.76 kg, average BMI is 24.14 kg/m2, and WHR is 0.94 cm. In the Control group, the average height is 1.58 m, weight is 62.42 kg, BMI is 24.42 kg/m2, and WHR is 0.95 cm.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD (min–max) | Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 68.97 ± 5.11 (60–79) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.28 ± 1.10 (21.30–27.56) | |||

| WHR (cm) | 0.94 ± 0.05 (0.82–1.27) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48 (50) | |||

| Female | 48 (50) | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Living with other | 24 (25) | |||

| Married | 53 (55.2) | |||

| Widowed | 13 (13.5) | |||

| Single | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Not disclosed | 5 (5.2) | |||

| Education (years) | ||||

| 5–9 | 24 (25) | |||

| 10–12 | 45 (49.6) | |||

| >12 | 27 (28.1) | |||

|

|

||||

|

N

|

||||

| Tai Chi group | Control group | |||

|

|

||||

| Number of participants | 48 | |||

| Male | 24 | 24 | ||

| Female | 24 | 24 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|

|

||||

| Age | 69.23 | 5.30 | 68.73 | 4.95 |

| Height (m) | 1.58 | 0.06 | 1.59 | 0.06 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.76 | 4.78 | 62.42 | 5.82 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.14 | 1.38 | 24.42 | 0.71 |

| WHR (cm) | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; WHR, waist–hip ratio.

During the intervention period, at the second phase (midpoint), three participants in the Tai Chi group dropped out because one did not want to take part and two left the city. Three participants in the Control group dropped out because one did not want to participate and two left the city. At the third phase (endpoint), six participants in the Tai Chi group dropped out: one of them refused to continue, two left the city, and three could no longer participate due to time constraints. Eleven participants in the Control group withdrew, four refused to continue, one had a sprained ankle, two left the city, and five had unknown reasons for leaving. At the final phase (follow-up), only 14 participants in the Tai Chi group took part in intervention. Others did not want to take part and had unknown reasons or could not participate due to lack of time.

Table 2 shows that there are no significant differences between Tai Chi and Control groups for all variables (P > 0.05) at baseline.

Table 2.

Comparisons of variables between Tai Chi and Control groups at baseline

| Dependent variables | Mean ± SD

|

Significance* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tai Chi (n = 48) | Control (n = 48) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.14 ± 1.38 | 24.42 ± 0.71 | 0.213 |

| WHR (cm) | 0.93 ± 0.064 | 0.95 ± 0.033 | 0.202 |

| Systole (mmHg) | 145.42 ± 10.21 | 147.40 ± 8.32 | 0.301 |

| Diastole (mmHg) | 81.48 ± 6.23 | 82.19 ± 5.18 | 0.547 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 84.48 ± 6.24 | 83.08 ± 4.46 | 0.211 |

| Chair stand (stands) | 16.31 ± 2.74 | 16.33 ± 2.56 | 0.969 |

| Arm curl (times) | 16.92 ± 2.54 | 16.62 ± 2.39 | 0.564 |

| 2-minute step (steps) | 88.12 ± 8.53 | 85.75 ± 6.96 | 0.139 |

| Chair sit reach (cm) | −1.10 ± 5.68 | −1.25 ± 5.73 | 0.901 |

| Back scratch (cm) | −2.23 ± 4.25 | −1.69 ± 4.45 | 0.544 |

| 8 foot up and go (second) | 6.98 ± 0.85 | 7.16 ± 0.67 | 0.231 |

| PCS (scale) | 51.81 ± 23.28 | 48.23 ± 23.86 | 0.458 |

| MCS (scale) | 52.19 ± 18.77 | 49.65 ± 20.34 | 0.526 |

| SF-36 total (scale) | 52.31 ± 22.42 | 48.69 ± 23.40 | 0.442 |

Note:

Determined by ANOVA.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist–hip ratio; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36, Short Form-36; bpm, beats per minute.

Table 3 shows that there are significant differences in any variables between the Tai Chi and Control groups at endtest except diastole blood pressure (significance of 0.093, P > 0.05). Most of variables have mean differences at significant level (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Comparisons of variables between Tai Chi and Control groups at endtest

| Dependent variables | Mean ± SD

|

Difference | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tai Chi (n = 39) | Control (n = 34) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.22 ± 1.24 | 24.45 ± 0.76 | −1.23 | 0.000* |

| WHR (cm) | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.001* |

| Systole (mmHg) | 134.51 ± 4.96 | 146.51 ± 6.54 | −12 | 0.000† |

| Diastole (mmHg) | 80.95 ± 3.63 | 82.41 ± 3.84 | −1.46 | 0.093 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 76.72 ± 3.23 | 82.86 ± 3.20 | −6.14 | 0.000* |

| Chair stand (stands) | 20.26 ± 2.39 | 16.00 ± 2.11 | 4.26 | 0.000* |

| Arm curl (times) | 20.69 ± 2.46 | 16.41 ± 2.13 | 4.28 | 0.000* |

| 2-minute step (steps) | 91.62 ± 6.28 | 84.50 ± 5.59 | 7.12 | 0.000* |

| Chair sit reach (cm) | 3.67 ± 3.23 | −0.65 ± 4.66 | 4.32 | 0.000† |

| Back scratch (cm) | 3.10 ± 2.68 | −1.74 ± 3.80 | 4.84 | 0.000* |

| 8 foot up and go (second) | 6.11 ± 0.71 | 7.22 ± 0.62 | −1.11 | 0.000* |

| PCS (scale) | 80.31 ± 6.85 | 47.32 ± 24.51 | 32.99 | 0.000† |

| MCS (scale) | 76.36 ± 5.76 | 49.53 ± 20.52 | 26.83 | 0.000† |

| SF-36 total (scale) | 80.18 ± 6.56 | 47.97 ± 24.52 | 32.21 | 0.000† |

Notes:

Student’s t-test;

Mann–Whitney test.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist–hip ratio; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36, Short Form-36; bpm, beats per minute.

Table 4 shows that there are no significant differences in correlation between variables of the two periods of test (endtest and follow up) in the Tai Chi group. It can be concluded that the effects of Tai Chi training remain in physical performance levels and subjectively perceived health as well as blood pressure for at least 8 weeks after stopping Tai Chi training.

Table 4.

Comparisons of variables between endtest and follow-up of the Tai Chi group

| Dependent variables | Mean (SD)

|

Difference | Ra | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endtest (n = 39) | Follow-up (n = 14) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.22 (1.24) | 23.40 (1.24) | −0.18 | 0.97 | 1.73 |

| WHR (cm) | 0.91 (0.05) | 0.93 (0.06) | −0.02 | 0.97 | 1.24 |

| Systole (mmHg) | 134.51 (4.96) | 135.50 (5.50) | −0.99 | 0.98 | 3.97 |

| Diastole (mmHg) | 80.95 (3.63) | 80.21 (3.76) | 0.74 | 0.98 | 5.41 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 76.72 (3.23) | 78.29 (2.33) | −1.57 | 0.98 | 1.39 |

| Chair stand (stands) | 20.26 (2.39) | 20.14 (2.24) | 0.12 | 0.89 | 3.40 |

| Arm curl (times) | 20.69 (2.46) | 20.00 (1.96) | 0.69 | 0.88 | 1.38 |

| 2-minute step (steps) | 91.62 (6.28) | 91.14 (7.22) | 0.48 | 0.96 | 2.41 |

| Chair sit reach (cm) | 3.67 (3.23) | 4.07 (3.95) | −0.4 | 0.08 | 0.60 |

| Back scratch (cm) | 3.10 (2.68) | 2.64 (3.00) | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| 8 foot up and go (s) | 6.11 (0.71) | 6.08 (0.64) | 0.03 | 0.89 | 3.46 |

| PCS (scale) | 80.31 (6.85) | 81.07 (5.78) | −0.67 | 0.95 | 1.49 |

| MCS (scale) | 76.36 (5.76) | 77.43 (4.45) | −1.07 | 0.96 | 3.75 |

| SF-36 total (scale) | 80.18 (6.56) | 81.36 (5.19) | −1.18 | 0.96 | 4.41 |

Notes:

Determined by Pearson regression (calculated by mean and difference presented in the Bland–Altman plots in Figures 1, 3, 5, and 6).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist–hip ratio; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36, Short Form-36; bpm, beats per minute.

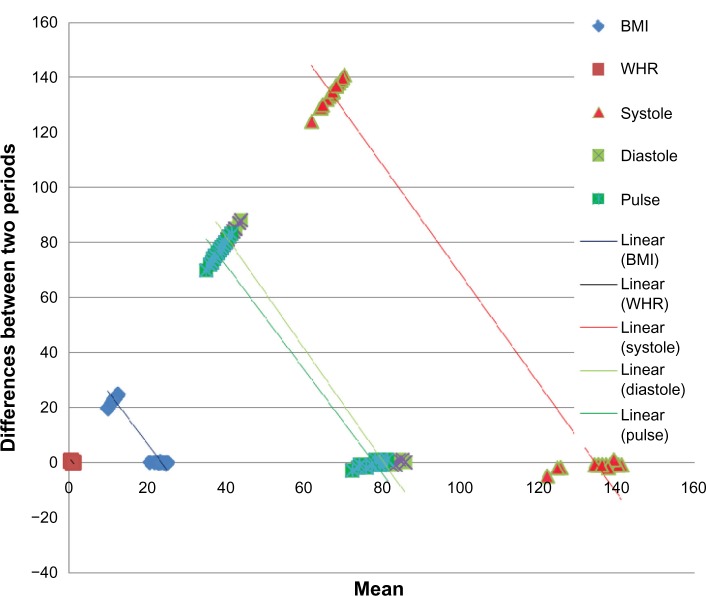

Figure 1 shows the Bland–Altman plots of data obtained from paired samples analyzed on the endtest and followup periods for BMI, WHR, and blood pressure. Significance for all factors was P > 0.05. BMI: correlation, R = 0.97; slope = −0.05; intercept = 23.31; WHR: R = 0.97, slope = −0.53; intercept = 0.93; systole: R = 0.98, slope = −0.49, intercept = 113.9; diastole: R = 0.98, slope = −0.47, intercept = 79.70; pulse: R = 0.98, slope = −0.51, intercept = 77.24, respectively.

Figure 1.

Differences between endtest and follow-up periods for BMI, WHR, and blood pressure of the Tai Chi group.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist–hip ratio.

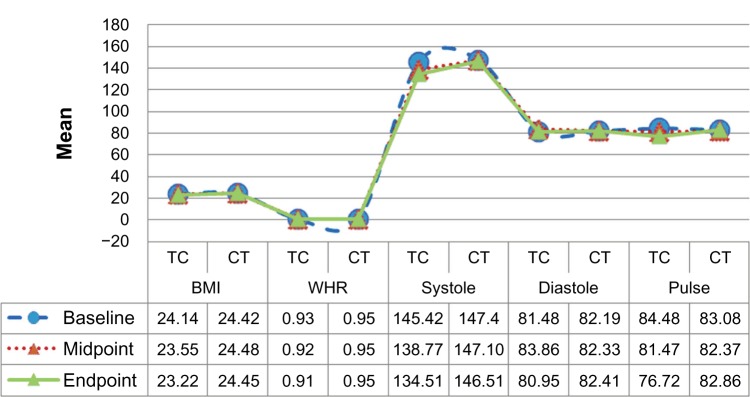

Tai Chi group shows better results than the Control group for BMI, WHR, and blood pressure at three test periods (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean BMI, WHR, and blood pressure of the Tai Chi and Control groups at three test times.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CT, Control group; TC, Tai Chi group; WHR, waist–hip ratio.

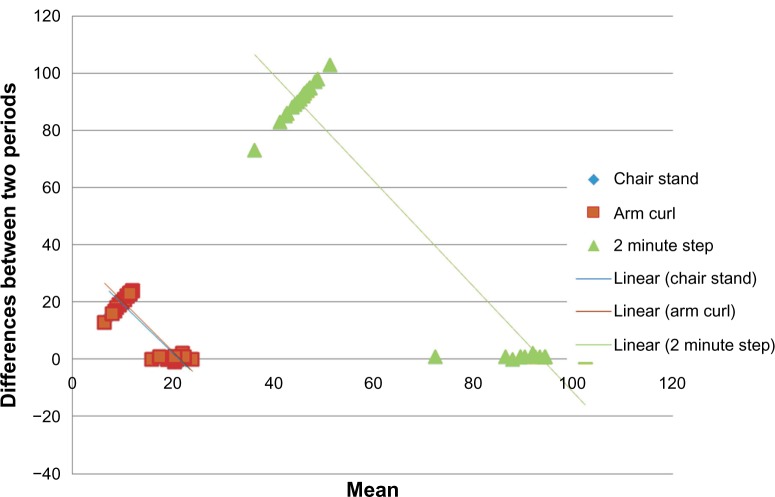

Figure 3 shows the Bland–Altman plots of data obtained from paired samples analysed on the endtest and follow up periods for lower-upper strength, and endurance. Significance for all was P > 0.05. Chair stand: R = 0.89, slope = −0.46, intercept = 19.81; arm curl: R = 0.88, slope = −0.44, intercept = 19.93; 2-minute step: R = 0.96, slope = −0.49, intercept = 19.49, respectively.

Figure 3.

Differences between endtest and follow-up periods for senior fitness test (lower and upper strength) of the Tai Chi group.

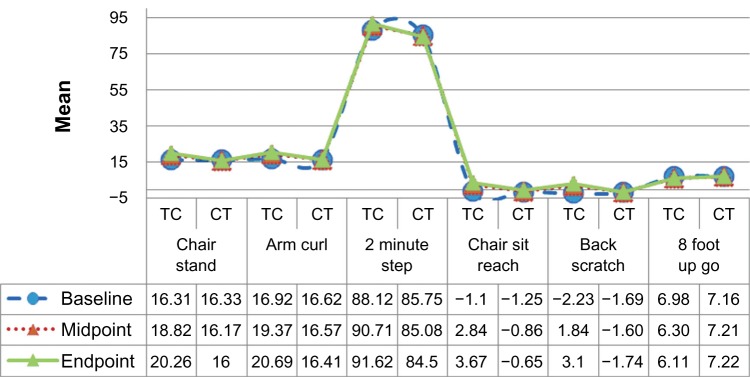

The Tai Chi group showed better physical fitness peformance than the Control group at three test periods (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean SFT of the Tai Chi and Control groups at three test times.

Abbreviations: CT, Control group; SFT, Senior Fitness Test; TC, Tai Chi group.

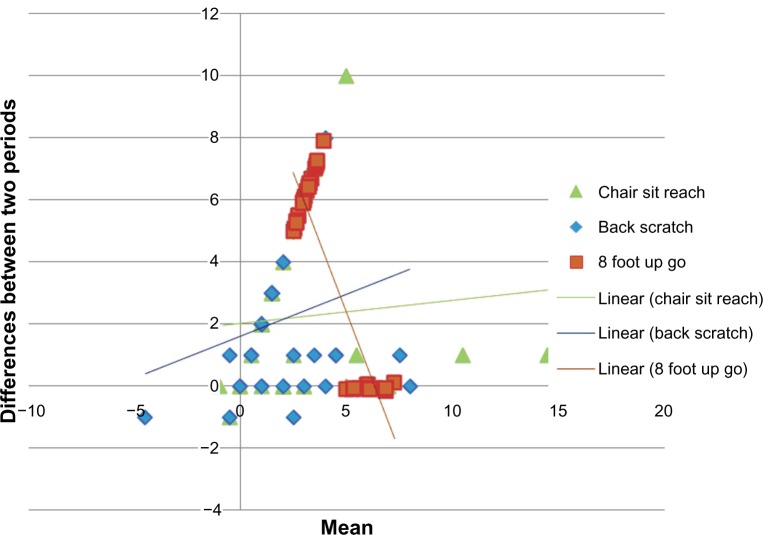

Figure 5 shows the Bland–Altman plots of data obtained from paired samples analyzed on the endtest and follow-up periods for lower-upper flexibility and dynamic balance. Significance for all was P > 0.05. Chair sit reach: R = 0.085, slope = 0.09, intercept = 2.34; back scratch: R = 0.059, slope = 0.21, intercept = 1.55; 8 foot up and go: R = 0.89, slope = −0.44, intercept = 5.87, respectively.

Figure 5.

Differences between endtest and follow-up periods for SFT (lower-upper flexibility and dynamic balance) of the Tai Chi group.

Abbreviation: SFT, Senior Fitness Test.

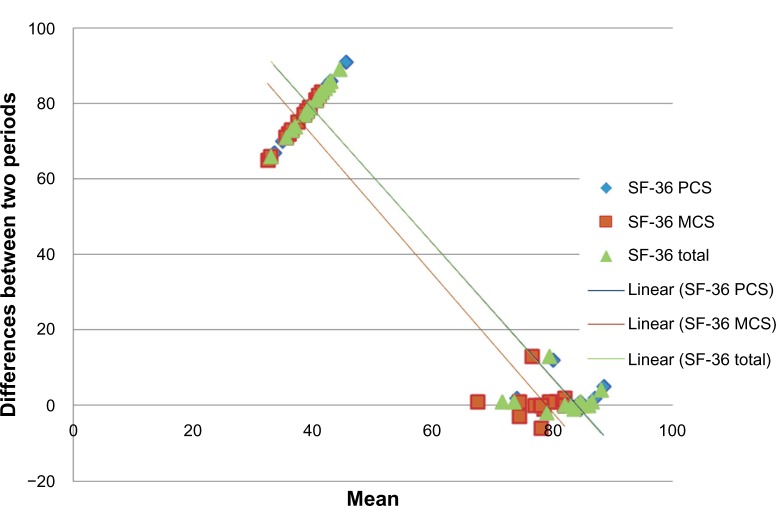

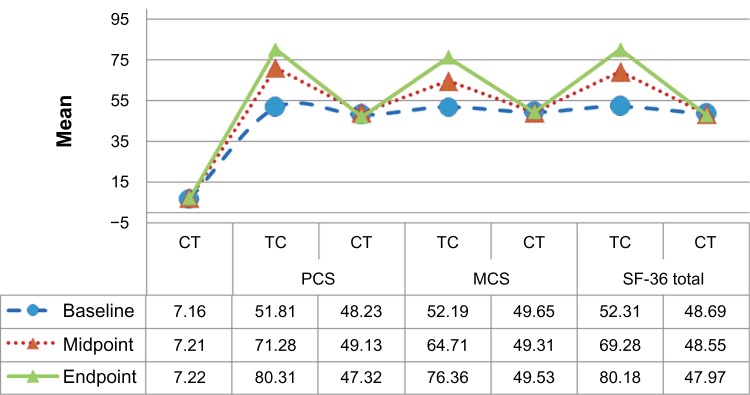

Figure 6 shows the Bland–Altman plots of data obtained from paired samples analysed on the endtest and follow-up periods for perceived health. Significance for all was P > 0.05. PCS: R = 0.95, slope = −0.51, intercept = 81.70; MCS: R = 0.09, slope = −0.51, intercept = 77.39; SF-36 total: R = 0.96, slope = −0.51, intercept = 81.89, respectively. The Tai Chi group reported better scores in perceived health than the Control group at three test periods (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Differences between endtest and follow-up periods for SF-36 (PCS, MCS, and SF-36 total) for Tai Chi group.

Abbreviations: MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36, Short Form-36.

Figure 7.

Mean SF-36 of the Tai Chi and Control groups at three test times.

Abbreviations: CT, Control group; MCS, mental component summary; PCS, physical component summary; TC, Tai Chi group.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the effects of a 24-form Tai Chi exercise in 6 months on physical fitness, blood pressure, and perceived health of community-dwelling elderly. On the basis of this study, it may be concluded that a 24-week Tai Chi training course does not affect the diastole variable. However, we found Tai Chi improved BMI, WHR, systole, pulse, physical fitness, and perceived health.

Previous findings supported Tai Chi as a measure to improve balance and blood pressure for middle-aged women.16,17 The present Tai Chi training improved systolic blood pressure and pulse, but did not improve diastolic blood pressure. This is consistent with the finding of Ko18 that a 10-week Tai Chi exercise program improved systolic blood pressure, lipid profiles, and some parameters of health-related quality of life in Hong Kong women. Tai Chi is a traditional Chinese aerobic exercise. Its benefits are to improve balance, flexibility, muscle strength, neuromuscular reaction, and endurance in elderly individuals.19–22 It was also reported that a high level of physical activity was associated with better scores in quality of life assessments.23

Based on previous studies, we know that Tai Chi enhances physiological well-being and improves cardiopulmonary functions related to quality of life.18,24–26 Tai Chi can improve quality of life among the elderly27 and its characteristics are highly relevant for promoting health among elderly, and is particularly effective in nursing home residents.28 Tai Chi increased subjective health and decreased stress.29 In our study, we also found that Tai Chi improved physical functions in community-dwelling elderly. It has been indicated that Tai Chi has a primary effect on strength, balance, and overall physical functioning.8 Caminiti and colleagues30 reported that the association of Tai Chi and education training improves the exercise tolerance of patients with chronic heart failure than with education training alone. Tai Chi appears to be beneficial for strength and aerobic training.31 Jacobson and colleagues32 reported that a 12-week Tai Chi program could improve the muscular strength of knee extensors. The present study also indicates that Tai Chi participants outperformed their counterparts in the Control group in almost all parameters of physical and mental health. Previous studies demonstrated that regular Tai Chi exercise leads to improvement in postural stability, functional mobility, and balance control.19,33–36

Over the 6-month Tai Chi program, we had a 18.75% drop-out rate (not including the follow-up period) in the Tai Chi group. This is evident that a relatively high rate of participants was likely to engage in Tai Chi training. The attrition of participation was due mainly to travelling or leaving the city rather than dissatisfaction with training program. Tai Chi is a low-technology exercise that can be easily carried out in a variety of communities.

This study has several limitations, such as small sample size, low-frequency training schedule with only two sessions per week. The follow-up period should be longer to examine how long the effects of Tai Chi remain. The follow-up group should be large enough for reliable statistical calculation. Furthermore, we have used two research groups while the Tai Chi group received treatment but the Control group did not. The social effects or biased opinions resulting from individuals in both groups might be raised. It should be, therefore, a comparative design that accounts for equal intervention conditions. Moreover, all participants come from urban areas that may not be representative for the whole Vietnamese population.

Conclusion

In this randomized controlled trial study, Tai Chi is beneficial to improve systole blood pressure, heart rate, BMI, WHR, perceived health, and physical fitness. Assessment of the effects of Tai Chi may be focused more on chronic disease with a long-term training program in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. 3612/QD-BGDDT from the Vietnam International Education Development, Travel Grant from Graduiertenakademie Universität Heidelberg/Heidelberg University Graduate Academy, 12.2010, and Institute of Gerontology, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Authors’ contributions

AK had substantial contributions to the study conception and design, supervised the study, and critically revised the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this work. The study sponsors played no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Brill PA. Functional fitness for older adults. Champaign, III: Human Kinetics. 2004:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang JG, Ishikawa TK, Yamazaki H, Morita T, Ohta T. The effects of Tai Chi Chuan on physiological function and fear of falling in the less robust elderly: An intervention study for preventing falls. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;42(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi JH, Moon JS, Song R. Effects of Sun-style Tai Chi exercise on physical fitness and fall prevention in fall-prone older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong SM, Ng GY. The effects on sensorimotor performance and balance with Tai Chi training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, McAuley E. Delineating the impact of Tai Chi training on physical function among the elderly. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(Suppl 2):92–97. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li F, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, McAuley E, Chaumeton NR, Harmer P. Enhancing the psychological well-being of elderly individual through Tai Chi exercise: A latent growth curve analysis. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:53–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh GY, Wang C, Wayne PM, Phillips RS. The effect of tai chi exercise on blood pressure: a systematic review. Prev Cardiol. 2008;11(2):82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2008.07565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li F, Harmer P, McAuley E, Fisher KJ, Duncan TE, Duncan SC. Tai Chi, self-efficacy, and physical function in the elderly. Prev Sci. 2001;2(4):229–239. doi: 10.1023/a:1013614200329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan C, Lai JS, Chen SY, Wong MK. 12-month Tai Chi training in the elderly: its effect on health fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(3):345–351. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin MR, Hwang HF, Wang YW, Chang SH, Wolf SL. Community-based tai chi and its effect on injurious falls, balance, gait, and fear of falling in older people. Phys Ther. 2006;86(9):1189–1201. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20040408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J. The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(5):493–501. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rikli R, Jones CJ. Senior Fitness Tests Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Harmer P, McAuley E, et al. An evaluation of the effect of Tai Chi exercise on physical function among older persons: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2001;2:89–101. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YH, Devault CN, Van Oteghen S. Effects of extended Tai Chi intervention on balance and selected motor functions of the elderly. Am J Chinese Med. 2007;35(3):383–391. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X07004904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton EW, Sykes KS, Tang WK. Health benefits of Tai Chi exercise: improved balance and blood pressure in middle-aged women. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(1):33–38. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai JC, Wang WH, Chan P, et al. The beneficial effects of Tai Chi Chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(5):747–754. doi: 10.1089/107555303322524599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko GT, Tsang PC, Chan HC. A 10-week Tai-Chi program improved the blood pressure, lipid profile and SF-36 scores in Hong Kong Chinese women. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(5):CR196–CR199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong Y, Li JX, Robinson PD. Balance control, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness among older Tai Chi practitioners. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(1):29–34. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan C, Lai JS, Chen SY, Wong MK. Tai Chi Chuan to improve muscular strength and endurance in elderly individuals: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(5):604–607. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, Hillsdon M, Narici M, Van Der Bij AK. Physical activity and older adults: a review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. J Sports Sci. 2004;22(8):703–725. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001712421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu DQ, Li JX, Hong YL. Effect of regular Tai Chi and jogging exercise on neuromuscular reaction in older people. Age Ageing. 2005;34(5):439–444. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drewnowski A, Evans WJ. Nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:89–94. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeeuwe PE, Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Rossum E, Faber MJ, Koes BW. The effect of Tai Chi Chuan in reducing falls among elderly people: design of a randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands [ISRCTN98840266] BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutner NG, Barnhart H, Wolf SL, McNeely E, Xu TS. Self-report benefits of Tai Chi practice by older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(5):P242–P246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.5.p242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YT, Taylor L, Pearl M, Chang LS. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on physical and mental health of college students. Am J Chin Med. 2004;32(3):453–459. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X04002107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho TJ, Liang WM, Lien CH, et al. Health-related quality of life in the elderly practicing T’ai Chi Chuan. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1077–1083. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee LY, Lee DT, Woo J. Tai Chi and health-related quality of life in nursing home residents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esch T, Duckstein J, Welke J, Braun V. Mind/body techniques for physiological and psychological stress reduction: Stress management via Tai Chi training – a pilot study. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(11):488–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caminiti G, Volterrani M, Marrzzi G, Cerrito A, et al. Tai Chi enhances the effects of endurance training in the rehabilitation of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Rehabil Res Pract. 2011;2011:761958. doi: 10.1155/2011/761958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young DR, Appel LJ, Jee SH, Miller ER. The effects of aerobic exercise and Tai Chi in blood pressure in older people: Results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson BH, Chen HC, Cashel C, et al. The effect of Tai Chi Chuan training on balance, knesthetic sense, and strength. Percept Mot Skills. 1997;84:27–33. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.84.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin YC, Wong AM, Chou SW, Tang FT, Wong PY. The effects of Tai Chi Chuan on postural stability in the elderly: preliminary report. Chang Gung Med J. 2000;23(4):197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross MCBA, Davis DC, Gurchiek L. The effects of a short-term exercise program on movement, pain, and mood in the elderly. J Holist Nurs. 1999;17:139–147. doi: 10.1177/089801019901700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf LS, Barnhart HX, Kutner NG, et al. Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: An investigation of Tai Chi and computerized balance training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:489–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfson L, Whipple R, Derby C, et al. Balance and strength training in older adults: intervention gains and Tai Chi maintenance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(5):498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]