Abstract

Context

Cost-related medication nonadherence (CRN) has been a persistent problem for elderly and disabled Americans. The impact of Medicare prescription drug coverage (Part D) on CRN is unknown.

Objectives

To estimate changes in CRN and forgoing basic needs to pay for drugs following Part D implementation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In a population-level design, we compared changes in study outcomes from 2005 to 2006, before and after Part D, to historical changes from 2004 to 2005. We used the community-dwelling sample of the nationally representative Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (unweighted unique n=24,234, response rate =72.3%) Logistic regression analyses controlled for demographic characteristics, health status, and historical trends.

Main Outcome Measures

Self-reports of cost-related nonadherence (skipping or reducing doses, not obtaining prescriptions) and spending less on basic needs in order to afford medicines.

Results

The unadjusted, weighted prevalence of CRN was 15.2% in 2004, 14.1% in 2005, and 11.5% after Part D in 2006; the prevalence of spending less on basic needs was 10.6% in 2004, 11.1% in 2005, and 7.6% in 2006. Adjusted analyses comparing 2006 to 2005, controlling for historical changes (2005 versus 2004), demonstrated significant decreases in the odds of CRN (OR ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74–0.98; P = .03) and spending less on basic needs (OR ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.48–0.72; P < .000). No significant changes in CRN were observed among beneficiaries with fair-to-poor health (OR ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82–1.21; P = .97), despite high baseline CRN prevalence for this group (22.2% in 2005) and significant decreases among those with good-to-excellent health (OR ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63–0.95; P = .02). However, we did detect significant reductions in spending less on basic needs in both groups (OR ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47–0.75; P < .000, for fair-to-poor health; OR ratio, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.44–0.75; P < .000 for good-to-excellent health).

Conclusions

In this survey population, there was evidence for a small but significant overall decrease in cost-related nonadherence and forgoing basic needs following Part D implementation. However, we detected no net decrease in CRN after Part D among the sickest beneficiaries, who continued to experience higher rates of CRN.

In perhaps the most extensive restructuring of the Medicare system since its introduction in 1965, Congress passed the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA) in the fall of 2003. Prior to the MMA, millions of elderly and disabled had insufficient or no insurance coverage for outpatient medications.1,2,3 In the face of these economic barriers, several large surveys have shown that older Americans have resorted to behaviors such as skipping doses, reducing doses, and letting prescriptions go unfilled.4,5,6,7,8,9 Such cost-related medication nonadherence (CRN) is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and preventable hospitalization.10

Since January 2006, Medicare beneficiaries may elect to purchase a prescription drug benefit (Part D), subsidized by Medicare and available through private plans.11 Additional subsidies are available to low-income beneficiaries and those with very high drug costs. Recent data have shown that only about 10% of Medicare beneficiaries remain without prescription coverage after Medicare Part D implementation, compared with rates of 25–38% in the preceding years.2,4,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 The Congressional Budget Office projected total federal spending on Part D to be $850 billion over the first 10 years.19

There have been no published studies using longitudinal data to examine possible changes in CRN before and after Medicare Part D implementation. In this paper, we report changes in the prevalences of CRN and spending less on basic needs (e.g., food) in order to afford medicines among 24,234 nationally representative, community-dwelling Medicare enrollees who participated in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey during the fall seasons of 2004, 2005, and 2006. We estimated changes in CRN among respondents between 2005 and 2006, before and after Part D implementation, controlling for changes observed in identically defined populations in the two years before Part D implementation. To avoid selection biases due to greater Part D enrollment among sicker and poorer beneficiaries,20,21 we conducted full population analyses including all respondents regardless of Part D enrollment. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine changes in populations with demographic and health characteristics associated with CRN (e.g., fair-to-poor health).5

METHODS

Data Source and Sample

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services conducts the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) based on a representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries drawn from Medicare enrollment data.22 The MCBS is the principal national survey for informing and evaluating health policies for Medicare beneficiaries. A 4-year rotating panel design, with annual replenishments, ensures continued generalizability and allows longitudinal analyses. The annual survey population of approximately 15,700 Medicare enrollees is selected using a multistage sampling plan, with oversampling of vulnerable subgroups such as the disabled and the oldest old. MCBS conducts a baseline interview between September and December covering demographic and household factors, as well as health insurance, health status, and experiences with health care. This general interview is repeated yearly for the following 3 years. Additional thrice-annual interviews collect detailed information on health care use and expenditures, with reviews of respondents’ insurance statements and receipts to enhance data accuracy. Interviews are conducted in person with computer assistance. MCBS produces two data files annually, Access to Care (ATC) and Cost and Use (CAU). Since 2004, the MCBS has included in the fall interview and the ATC file a module of questions on different aspects of cost-related medication nonadherence (CRN), developed by the study team.4,5,6,23 We used MCBS data from only the ATC files in our analyses, because CAU files containing data on health care utilization after implementation of Part D will not become available until 2009. We included all community-dwelling respondents (approximately 94% of total) from 2004 through 2006; sample sizes by year are shown in Table 1. Accounting for overlap among years, the total number of individual respondents in this study was 24,234. Average ATC response rates across panels in this period were 72.3%.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and health characteristics of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries, 2004-2006a

| 2004 N=14,500 |

2005 N=14,701 |

2006 N=14,732 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 55.8 | (55.0, 56.6) | 55.8 | (54.9, 56.6) | 55.2 | (54.2, 56.1) |

| Ageb | ||||||

| Under 55 | 7.9 | (7.4, 8.5) | 7.8 | (7.3, 8.2) | 8.0 | (7.4, 8.6) |

| 55–64 | 7.0 | (6.4, 7.6) | 7.3 | (6.7, 8.0) | 7.5 | (6.9, 8.2) |

| 65–74 | 42.7 | (41.9, 43.6) | 42.5 | (41.6, 43.3) | 42.5 | (41.7, 43.4) |

| 75–84 | 32.2 | (31.3, 33.1) | 32.4 | (31.6, 33.2) | 31.6 | (30.9, 32.2) |

| 85 and over | 10.2 | (9.7, 10.6) | 10.1 | (9.7, 10.5) | 10.4 | (10.0, 10.9) |

| Income, $ | ||||||

| Less than $25,000 | 58.9 | (57.1, 60.6) | 57.5 | (55.8, 59.1) | 55.1 | (53.4, 56.8) |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 9.7 | (8.1, 11.5) | 9.4 | (7.9, 11.2) | 9.4 | (7.9, 11.2) |

| White | 83.9 | (82.0, 85.6) | 84.3 | (82.4, 86.0) | 84.0 | (82.4, 85.6) |

| Other | 6.4 | (5.7, 7.3) | 6.4 | (5.6, 7.2) | 6.5 | (5.8, 7.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||||

| Hispanic | 7.8 | (6.7, 9.1) | 7.7 | (6.6, 8.9) | 7.8 | (6.7, 9.1) |

| Education | ||||||

| Above high school | 41.0 | (39.2, 42.9) | 42.1 | (40.2, 44.1) | 42.6 | (40.7, 44.5) |

| High school diploma | 30.4 | (29.1, 31.8) | 30.4 | (29.0, 31.9) | 30.9 | (29.7, 32.1) |

| No high school | 28.6 | (27.2, 30.0) | 27.5 | (26.0, 29.0) | 26.6 | (25.2, 28.0) |

| Number of morbiditiesc | ||||||

| 0–1 | 28.1 | (27.0, 29.1) | 26.5 | (25.5, 27.5) | 25.9 | (24.9, 27.0) |

| 2–3 | 47.9 | (46.9, 48.9) | 47.0 | (46.1, 47.9) | 48.1 | (47.1, 49.1) |

| 4+ | 24.0 | (23.2, 24.9) | 26.5 | (25.6, 27.5) | 26.0 | (25.0, 27.0) |

| Number of limitations in | ||||||

| 0 | 70.7 | (69.3, 72.0) | 70.0 | (68.9, 71.2) | 69.9 | (68.3, 71.6) |

| 1–2 | 20.6 | (19.6, 21.7) | 21.0 | (20.0, 22.1) | 20.4 | (19.2, 21.6) |

| 3+ | 8.7 | (7.9, 9.6) | 8.9 | (8.3, 9.7) | 9.7 | (8.9, 10.6) |

| Self-reported health status | ||||||

| Excellent, very good, or good | 73.0 | (72.0, 74.1) | 73.2 | (72.1, 74.3) | 73.3 | (72.2, 74.5) |

| Fair or poor | 27.0 | (25.9, 28.1) | 26.8 | (25.7, 27.9) | 26.7 | (25.6, 27.8) |

Abbreviation: ADLs, activities of daily living

Percentage bases excluded those with missing values. Drug coverage type was missing for 3.5% of respondents; other characteristics missing for no more than 2%. Percentages calculated with national survey weights.

Respondents aged less than 65 years were defined as disabled.

Morbidity categories included cardiac disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, lung disease, cancer, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, psychiatric disorder or depression, dementia, and other neurological conditions.

Limitations in ADLs indicate reduced functional status.

Study Variables

In 2004, the MCBS incorporated a battery of validated measures of cost-related nonadherence (“decide not to fill or refill a prescription because it was too expensive”; “skipped doses to make the medicine last longer”; “taken smaller doses of a medicine to make the medicine last longer”), as well as a companion measure of extreme compensatory behaviors, “spent less money on food, heat, or other basic needs so that you would have money for medicine.”5 Previous work has shown that all four measures exhibit high test-retest reliability23 and construct validity.4,5,6

As described previously,5 we constructed a summary indicator of CRN for analysis which took the value yes if a respondent indicated yes/ever during the current year on any of the following: “skipped doses to make the medicine last longer”; “taken smaller doses of a medicine to make the medicine last longer”; or, “any medicines prescribed for you that you did not get” in combination with “(a reason or the main reason) you did not obtain the medicine was you thought it would cost too much” or “decide not to fill or refill a prescription because it was too expensive”. Preliminary analyses revealed that the reported prevalence of CRN and spending less on basic needs was higher in initial MCBS interviews than in subsequent annual interviews, irrespective of calendar year. We controlled for this interview sequence effect by incorporating MCBS sample replenishments in all years, estimating changes before and after Part D relative to a historical period without the same sequence effect, and adjusting all models for interview sequence.

From the MCBS ATC file, we used previously validated covariates5,6,24,25,26,27 to explore possible differences in population groups over time and as control variables in regression analyses. These covariates were all self-reported by survey respondents: demographic information (race, Hispanic ethnicity, age, gender, income, education); general health status (using a single-item measure28 dichotomized into fair or poor vs. good, very good, or excellent); functional status (using a 6-item assessment of limitations in activities of daily living29); and, presence of specific diseases/conditions (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

First, we described the rates (and 95% confidence intervals) of demographic and health characteristics of the population in 2004, 2005, and 2006, weighted to represent the overall population of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. We calculated unadjusted annual prevalences of cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs with 95% confidence intervals from 2004 to 2006.

To model changes in cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs over time, we used a logistic regression model and the full population in each calendar year to predict the odds of CRN (1=yes, 0=no) by year. The key covariates in the model were two indicators for response year (2006, 2005), with 2004 as the reference year. In addition to the odds ratio of CRN in 2005 versus 2004 produced directly by the model, we used contrast terms to estimate the odds ratio of CRN for 2006 versus 2005. Finally, we calculated a ratio of these two ORs, namely 2006 versus 2005 relative to 2005 versus 2004. This approach estimated the change in study outcomes following Part D implementation, controlling for historical year-to-year changes in the absence of Part D.

Our model controlled for interview sequence, demographic characteristics (gender, age, income, race), and health status (number of morbidities, general health status) using dummy variables, and applied MCBS cross-sectional survey weights.22 We corrected for the clustering at the primary sampling unit level inherent in the MCBS design,22 thereby also controlling for repeated responses by individuals over time.30 The odds of forgoing basic needs were modeled separately using the same approach. We then repeated both analyses separately in subgroups based on demographic and health characteristics determined earlier5 to be associated with CRN (e.g., disabled versus elderly, fair-to-poor versus good–to-excellent health, number of morbidities, and lower [<$25,000] versus higher income).

Because odds ratios can sometimes exaggerate risk ratios (RRs), we also converted ORs into RRs using previously validated methods31,32 and repeated the analyses. The results using risk ratios were nearly identical to those from the OR models. However, as no established methods exist for constructing precise confidence intervals or P values for RR ratios, we report the results from the OR models.

We assessed the robustness of our results by conducting three alternative analyses: adjustment for repeated measures on the same individuals across survey years using unweighted general estimating equation regression models; adjustment for drug coverage status5 prior to Part D for a subgroup of long-term survey respondents; and, two-year continuous cohort models, stratified by interview sequence, to investigate individual pre-post changes in mutually exclusive comparison groups (2005 to 2006 versus 2004 to 2005). These alternative approaches had little to no impact on estimates of changes in CRN and forgoing basic needs after Part D. We also determined that there were no differences in these outcomes between respondents who re-interviewed versus those who were lost to follow-up.

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) and the a priori level of statistical significance was P <.05

RESULTS

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries, 2004 to 2006

The demographic and health characteristics of the community-dwelling Medicare population in 2004, 2005, and 2006 were very similar (Table 1). A majority lived in low income (<$25,000) households. Disabled non-elderly beneficiaries represented about 15% of the weighted sample. Over 72% of beneficiaries were estimated to have at least 2 morbid conditions.

Unadjusted changes in study outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries, 2004–2006

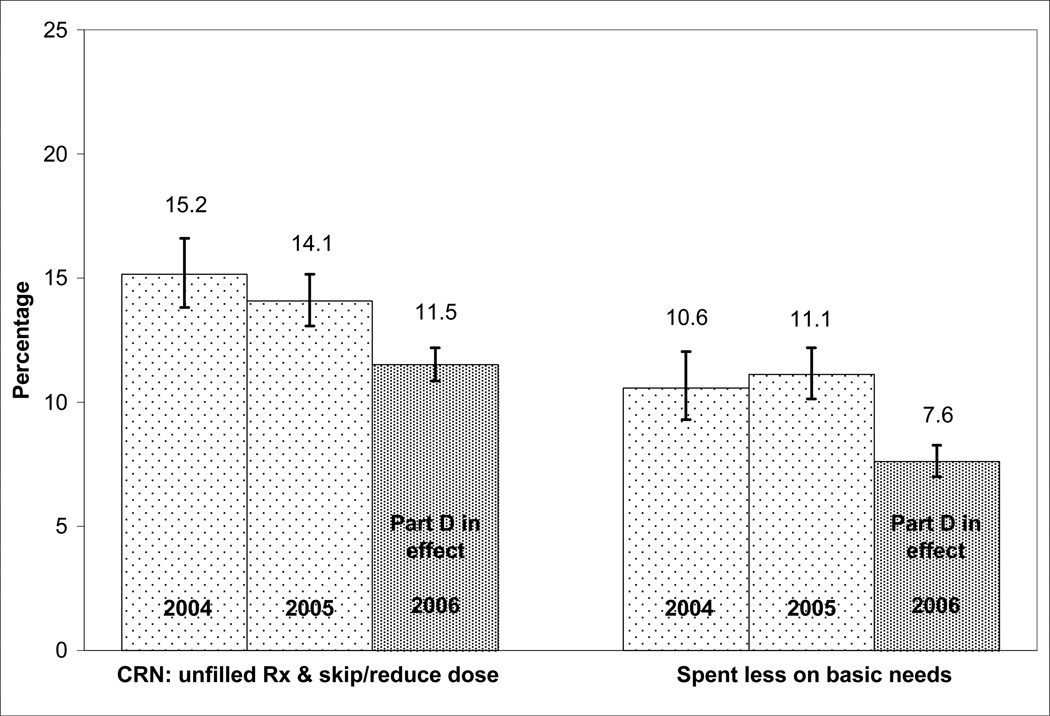

Figure 1 displays unadjusted year-to-year changes in the prevalence of cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs to afford medicines among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. We observed a larger absolute decrease in CRN following Medicare Part D implementation (from 14.1% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2006) than occurred between 2004 and 2005 (15.2% to 14.1%). At the same time, while forgoing basic needs rose slightly between 2004 and 2005 (10.6% to 11.1%), there was a 3.5 percentage point decrease (to 7.6%) in this measure after Part D in 2006. The overlaps in 95% CIs for the above measures between 2004 and 2005 and the lack of overlap in CIs between 2005 and 2006 suggest significant overall declines in unadjusted CRN and forgoing basic needs from 2005 to 2006 compared to historical changes.

FIGURE 1.

Unadjusted prevalence rates of cost-related medication nonadherence and spending less on basic needs among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries, 2004–2006a

Abbreviation: CRN, cost-related medication nonadherence

a Survey results weighted to national Medicare population. N ~37 to 38 million; item response rates, survey sample size, and Medicare target population vary by year and study measure. Brackets represent 95% confidence intervals around rates.

Adjusted changes in CRN

Table 2 shows overall estimated changes in cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs after the implementation of Part D, from logistic regression analyses. The 2006 versus 2005 odds ratio for cost-related nonadherence, relative to historical changes, was 0.85 (95% CI for OR ratio, 0.74–0.98), and the corresponding odds ratio for forgoing basic needs after Part D was 0.59 (95% CI for OR ratio, 0.48–0.72).

TABLE 2.

Overall changes in cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs following Part D implementation among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiariesa

| Outcome measure |

Odds Ratio 2005 vs. 2004 OR (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio 2006 vs. 2005 OR (95% CI) |

Ratio of ORs: 2006-2005 vs. 2005-2004 (95% CI) |

P-value for Ratio of ORs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-related nonadherence | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) | 0.85 (0.74, 0.98) | 0.030 |

| Spent less on basic needs | 1.07 (0.94, 1.21) | 0.63 (0.55, 0.72) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.72) | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

N=43,011 observations, 23,792 respondents for CRN; 42,923 observations, 23,776 respondents for spending less. Models adjusted for number of years’ participation in MCBS, sex, age group, income level, race, general health status, and number of morbidities, as defined in Table 1. All covariates were statistically significant in both models at the p=0.05 level, except “other” race (white= reference category) in both models, and 2nd and 3rd year of MCBS participation (4th=reference category) in CRN model. All results weighted to national population.

Findings for subgroups based on health status and income

Results from the subgroup analyses are presented in Table 3. As expected, prevalence rates in 2005 (before Part D) indicated that cost-related nonadherence was strongly associated with disabled status, poorer self-reported health, higher numbers of morbidities, and lower income. For example, in 2005, the prevalence of CRN among disabled non-elderly beneficiaries was 29.7%, while the prevalence of forgoing basic needs was 24.6%. Among the elderly, these rates were 11.3% and 8.8%, respectively. Those in fair-to-poor health status reported nearly double the rate of CRN (22.2%) and three times the rate of forgoing basic needs (21.3%) as compared with those in good-to-excellent health.

TABLE 3.

Changes in cost-related nonadherence and spending less on basic needs following Part D implementation among subgroups of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiariesa

| Subgroup Model | Nb | Cost Related Nonadherence | Spent Less on Basic Needs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Prevalencec 2005 (%) (95% CI) |

Ratio of ORs 2006-2005 vs. 2005-2004 (95% CI) |

P value for Ratio of ORs |

Unadjusted Prevalencec 2005 (%) (95% CI) |

Ratio of ORs 2006-2005 vs. 2005-2004 (95% CI) |

P value for Ratio of ORs |

||

| Elderly | 35,583 | 11.3 (10.4–12.3) | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 0.030 | 8.7 (7.8–9.7) | 0.49 (0.39–0.61) | 0.000 |

| Non-elderly disabled | 7,428 | 29.7 (26.9–32.6) | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) | 0.411 | 24.6 (22.1–27.2) | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | 0.178 |

| Health Status: | |||||||

| Good-to-excellent | 31,294 | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 0.77 (0.63–0.95) | 0.015 | 7.4 (6.6–8.4) | 0.57 (0.44–0.75) | 0.000 |

| Fair-to-poor | 11,717 | 22.2 (20.5–23.9) | 1.00 (0.82–1.21) | 0.970 | 21.3 (19.6–23.2) | 0.60 (0.47–0.75) | 0.000 |

| No. Morbidities | |||||||

| 0 to 1 | 11,332 | 9.6 (8.2–11.1) | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.080 | 6.5 (5.4–7.8) | 0.55 (0.37–0.82) | 0.004 |

| 2 to 3 | 20,570 | 14.4 (13.0–15.9) | 0.79 (0.64–0.97) | 0.025 | 10.7 (9.5–11.9) | 0.52 (0.40–0.68) | 0.000 |

| 4+ | 11,109 | 18.0 (16.6–19.5) | 1.04 (0.83–1.30) | 0.761 | 16.4 (14.9–18.0) | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.002 |

| Income | |||||||

| <$25,000 | 25,897 | 17.3 (16.1–18.6) | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | 0.003 | 15.0 (13.7–16.4) | 0.60 (0.49–0.74) | 0.000 |

| ≥$25,000 | 17,114 | 9.7 (8.7–10.9) | 1.02 (0.79–1.32) | 0.877 | 5.9 (5.0–6.9) | 0.53 (0.36–0.79) | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Models included national survey weights

Total number of observations for cost-related nonadherence in 2004, 2005, and 2006. There are 88 fewer total observations for the spent less on basic needs outcome

Prevalence rates weighted to national population

We did not detect any significant changes in CRN following Part D among the clinically more vulnerable subgroups (disabled, fair-to-poor health, and 4 or more morbidities, see Table 3), although among disabled respondents the sample was relatively small and the direction of change was downward (OR ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.69–1.16). Among the subgroups with fair-to-poor health or 4 or more morbidities, the OR ratios were ≥ 1, suggesting no change in CRN after Part D. Among those with 0–3 morbidities or good-to-excellent health, the OR ratios (Table 3) suggest some declines in CRN (in the case of 0–1 morbidities, the decline was not significant.) There were modest and significant declines in CRN among lower income beneficiaries, controlling for changes from 2004 to 2005, but not for higher income beneficiaries (Table 3).

The risk of forgoing basic needs declined among all subgroups, relative to historical changes, though the decline was not significant for the non-elderly disabled.

COMMENT

The inclusion of prescription drug coverage in Medicare represents the largest expansion of the program in over 40 years; it came after decades of media and scientific reports on the increasing financial burden of life-saving medicines for Medicare enrollees,1 nonadherence due to costs,4,5,6,7,9 and subsequent adverse health outcomes.10 A principal goal of Part D was to increase economic access to medications, especially among vulnerable poor and chronically ill populations. This is the first controlled study in a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries of changes in cost-related nonadherence and financial hardship after implementation of Part D.

Our data suggest that the implementation of Part D was associated with a modest but significant decline in the prevalence of cost-related nonadherence. In absolute terms, unadjusted prevalences of CRN and spending less on basic needs declined 2.6 and 3.5 percentage points, respectively; adjusted OR ratios were 0.85 and 0.59. Similar results were found for elderly Medicare beneficiaries, but our findings were inconclusive for the non-elderly disabled. We did not observe a decline in CRN among the sickest patients with fair-to-poor health or ≥ 4 morbidities; however, these groups reported some reductions in forgoing basic needs to afford medication. Those with incomes below $25,000 also experienced significant declines in CRN and forgoing basic needs, relative to historical trends.

The finding of only small absolute changes following implementation of Part D was predictable given our full-population design, which included all non-institutionalized MCBS respondents, regardless of whether they enrolled in Part D. Many Medicare beneficiaries already had drug coverage prior to Part D. Probably less than a quarter acquired drug coverage for the first time in 2006, while drug coverage was strengthened for other beneficiaries, particularly those in Medicare Advantage plans (managed care).9 Our findings provide an estimate of the national effect of the policy, rather than the effect on specific population subgroups who enrolled in Part D. The population-level approach is not subject to selection biases that result from higher rates of Part D enrollment among sicker patients.20,21

The lack of observed change in CRN among the disabled and those in poorer health deserves comment. We have shown here and in previous studies4,5,6,7 that the disabled and other Medicare beneficiaries in poor health have very high and persistent CRN over time, caused in part by intensive use of medication and high out-of-pocket medication expenditures.8,16,33,34,35 Further, those not enrolling in Part D or switching to Part D from other drug coverage would not be expected to exhibit substantial changes in CRN. For example, the disabled were more likely than elderly beneficiaries to have had Medicaid drug coverage prior to 2006 (30% versus 7%),5 and Medicaid recipients were autoenrolled into Part D plans. Less healthy beneficiaries who did enroll in a Part D plan would have paid substantially more in copayments than other beneficiaries and would more likely have fallen into the “doughnut hole” coverage gap (100% cost-sharing after exceeding $2250 in drug costs) by the end of the year, when this survey was conducted.11 Overall, our findings suggest that that the intensive medicine needs and financial barriers to access among the sickest beneficiaries may not have been fully addressed by Part D. A decline in CRN in the lower income group may reflect that the Medicare drug benefit provided additional subsidies to some low income beneficiaries.11

The observations in this report should also be considered in the context of concerns about specific aspects of the Part D benefit which could reduce its impact on CRN. For example, the size of the Part D subsidy varies considerably among beneficiaries.11 The complexity of Part D and initial confusion in its implementation may have led to uneven uptake or poor choices among available private plans.36 There has been little analysis so far of the differences in formularies and coverage policies across Part D plans, though such differences are strongly correlated with differences in adherence.37 However, this paper cannot explore the relative impact of different features of Part D, because we estimated population-wide effects of the benefit and the 2006 MCBS ATC data do not include benefit details.

The consistent reduction in the prevalence of forgoing food and basic needs to pay for medications merits discussion. To the extent that Part D reduced the burden of out-of-pocket prescription costs, a common initial effect of Part D might be to loosen constraints on the purchasing of food and other basic needs. Consequently, helping beneficiaries purchase medication may have economic and social effects that transcend medication adherence per se. Previous studies have documented that hunger and food insecurity are commonplace among careseekers in a public hospital setting38 and that some patients face difficult choices between food and medicines.39

This study has several limitations. We lack data on actual use of individual medications and health services after Part D, because 2006 utilization measures will not be available in the MCBS until 2009. Nevertheless, our measures of CRN and cutting back on basic needs are important intermediate outcomes of the Medicare drug benefit and have been shown to be reliable and valid in several previous studies.4,5,6,9,23 We used measures of cost-related nonadherence in fall MCBS surveys over three successive years (2004–2006). The 2006 round was conducted nine to twelve months after the launch of Part D, by which time much of the initial confusion40,41,42 should have subsided.

An additional CRN measure (delayed filling prescription because of cost) was added to the survey in 2006, but could not be used in our longitudinal analyses. Also in 2006, the MCBS began to ask all respondents directly about not filling prescription because of cost (instead of asking only a subset that first reported having failed to obtain a prescription for any reason). Although the summary CRN measure we used was fully comparable across the three years of observation, this measure underestimates CRN. A more complete summary measure, including all the CRN information available in the 2006 survey, would have resulted in a prevalence of CRN 37% higher for 2006 (15.8% instead of 11.5% in Figure 1) This undercounting is in addition to the well-established observation that people, particularly the elderly, underreport their health- and finance-related difficulties.43,44,45 The reasons for higher CRN among first-time respondents are unknown, but our design and alternative analyses largely precluded any confounding by duration of survey participation.

The two years of pre-policy data provide an important comparison and context for our analyses. However, an even longer pre-policy series would provide more clarity. Other factors unrelated to Part D (such as contemporaneous changes in the financial condition of Medicare beneficiaries) may have influenced observed changes in CRN before and after Part D implementation. Thus, our results should be considered early evidence until longer-term data are available. Nevertheless, the declines we found in CRN and spending less on basic needs after Part D were consistent across analytic approaches and suggest a positive population-level effect of the drug benefit. Characteristics known to predict CRN5 were nearly identical across the three years we observed (e.g., self-reported health, number of morbidities, etc), and controlling for these factors did not alter our conclusions. The reasons for an apparent historical decrease in CRN (between 2004 and 2005) are not known, but may include uptake of Medicare-approved drug discount cards – an interim form of assistance prior to Part D.46 Other state-level and company-sponsored assistance programs proliferated in recent years,3,6,47 and there was increased use of generics and drug purchasing by internet and mail-order, and from abroad.48,49 However, the median income and total non-housing assets of elderly Americans remained nearly constant between 2004 and 2006 (income, $30,858 to $30,100; assets $80,042 to $79,500, based on inflation-adjusted figures from the national Health and Retirement Survey50).

In summary, we found small but significant population-level declines in cost-related medication nonadherence and spending less on basic needs to afford medicines, nearly a year after an unprecedented shift in Medicare policy: the implementation of the Part D drug benefit. Those in poor health or with multiple morbidities, who had substantially higher baseline CRN, did not experience declines in CRN associated with Part D, although they did report reductions in spending less on basic needs. Further research is needed to determine which specific aspects of Part D did or did not alleviate the persistent burdens of medication costs. Part D claims data, linked to detailed Part D plan characteristics, must be made available to study the impact of the new Medicare drug benefit on actual utilization of medications and health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grants # R01AG028745 and # RO1 AG022362, and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation. Drs. Zhang, Briesacher, Ross-Degnan, Gurwitz, and Soumerai are investigators in the HMO Research Network Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics, supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant # 2U18HS010391).

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations did not participate in the design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Madden had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Madden, Soumerai, Zhang, Safran, Ross-Degnan, Adams, Briesacher, Gurwitz.

Acquisition of the data: Adler, Pierre-Jacques, Madden, Soumerai, Safran.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Madden, Soumerai, Graves, Zhang, Adams, Briesacher, Ross-Degnan, Gurwitz, Pierre-Jacques, Safran.

Drafting of the manuscript: Madden, Soumerai.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Madden, Soumerai, Adams, Briesacher, Ross-Degnan, Gurwitz, Safran, Graves, Zhang, Pierre-Jacques, Adler.

Statistical analysis: Graves, Zhang, Madden, Pierre-Jacques.

Obtained funding: Soumerai, Madden, Ross-Degnan, Adams, Zhang, Briesacher, Gurwitz, Safran.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Graves, Pierre-Jacques.

Study supervision: Madden, Soumerai.

Financial Disclosures: No financial disclosures reported.

Additional contributions: We are grateful for the generosity and insight of Franklin Eppig, JD, of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for helping us to integrate measures of CRN into the MCBS, and we thank Andrew Shatto of CMS for assistance with data access and definition. Michael Law, MSc, of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HMS & HPHC) gave helpful advice on modeling strategies and Alan Zaslavsky, PhD, of HMS was generous with statistical advice. We thank Robert LeCates, MA, of HMS & HPHC for assistance during manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Inadequate drug coverage in Medicare: A call to action. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:722–728. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. The case for a Medicare drug coverage benefit: a critical review of the empirical evidence. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001;22:49–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Ayanian JZ. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286:1732–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, Kitchman MS, Wilson I, Cooper B, Li A, Chang H, Rogers WH. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: where do things stand on the eve of implementing the new part d benefit? Findings from a 2003 National survey of seniors? Health Aff April. 2005;19:W5-152–W5-166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.152. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS, Gurwitz J, Adler G, Safran DG. Cost-related medication nonadherence among the elderly and the disabled: A national survey one year before the Medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1829–1835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, Montgomery JE, Li W, Wilson IB, Kitchman MS, Bowen AE, Rogers WH. Prescription Drug Coverage and Seniors: How Well Are States Closing the Gap? Health Aff July. 2002;31:W253–W268. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.253. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briesacher BA, Gurwitz JH, Soumerai SB. Patients at-risk for cost-related medication nonadherence: a review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:864–871. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson KW, Neuman P, Dutwin D, Kasper JD. Uncovering the health challenges facing people with disabilities: the role of health insurance. Health Aff November. 2003;19:W3522–W3565. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.552. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuman P, Strollo MK, Guterman S, Rogers WH, Li A, Rodday AM, Safran DG. Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report: findings from a 2006 national survey of seniors. Health Aff. 2007;26:w630–w643. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heisler M, Langa KM, Eby EL, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MU, Piette JD. The health effects of restricting prescription medication use because of cost. Med Care. 2004;42:626–634. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129352.36733.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed March 6, 2008];The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Fact Sheet. 2006 Jun; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044_04.pdf.

- 12.The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed on January 3, 2008];Overview of Medicare Part D Organizations, Plans and Benefits By Enrollment in 2006 and 2007. 2007 Nov; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7710.pdf.

- 13.The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed on January 3, 2008];Medicare Chartbook 2005. 2005 Summer; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/Medicare-Chart-Book-3rd-Edition-Summer-2005-Report.pdf.

- 14.Poisal JA, Chulis GS. Medicare Beneficiaries and Drug Coverage. Health Aff. 2000;19:251. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crippen DL. Projections of Medicare and Prescription Drug Spending. [accessed February 28, 2008];Statement before the Committee on Finance, United States Senate. 2002 Mar 7; Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/33xx/doc3304/03-07-MedicareSpending.pdf.

- 16.Stuart B, Simoni-Wastila L, Chauncey D. Assessing the impact of coverage gaps in the Medicare Part D drug benefit. Health Aff April. 2005;19:W5-167–W5-179. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.167. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart B, Shea D, Briesacher B. Dynamics in drug coverage of Medicare beneficiaries: finders, losers, switchers. Health Aff. 2001;20:86–99. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laschober MA, Kitchman M, Neuman P, Strabic AA. Trends in Medicare supplemental insurance and prescription drug coverage 1996–1999. Health Aff February. 2002;27:W127–W138. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.127. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Congress of the United States, Congressional Budget Office. [accessed March 6, 2008];An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2006. 2005 Mar;:42. CBO report: Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/61xx/doc6146/03-15-PresAnalysis.pdf.

- 20.Levy J, Weir DR. Take-Up of Medicare Part D and the SSA subsidy: early results from the Health and Retirement Study. Challenges and Solutions for Retirement Security; Prepared for the 9th annual joint conference of the retirement research consortium; August 9-10, 2007; Washington, DC. [accessed Dec 14, 2007]. Available at: http://www.mrrc.isr.umich.edu/publications/conference/pdf/UM07-06A0807C.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heiss F, McFadden D, Winter J. Who failed to enroll in Medicare Part D, and Why? Early Results. Health Aff. 2006;25:w344–w354. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appendix A. Sourcebook Series: Health and Health Care of the Medicare Population. [accessed Dec. 14, 2007];Technical Documentation for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Study. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2002. 2002 Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/mcbs/downloads/HHC2002appendixA.pdf.

- 23.Pierre-Jacques M, Safran DG, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Adams AS, Gurwitz J, Rusinak D, Soumerai SB. Reliability of New Measures of Cost Related Medication Nonadherence. Medical Care. 2008:46. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc59a. (In press, April) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Use of antihypertensive drugs by Medicare enrollees: Does type of drug coverage matter? Health Aff. 2001;20:276–286. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blustein J. Drug coverage and drug purchases by Medicare beneficiaries with hypertension. Health Aff. 2000;19:219–230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Briesacher B, Stuart B, Ren X, Doshi J, Wrobel MV. Medicare beneficiaries and the impact of gaining prescription drug coverage on inpatient and physician spending. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1279–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuart B, Shea D, Briesacher B. Prescription drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries: coverage and health status matter. Issue Brief (Commonwealth Fund) 2000:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:721–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarndal CE, Swensson B, Wretman J. Series: Springer Series in Statistics. 2nd edition. Springer Verlag; 2003. Nov, Model Assisted Survey Sampling, sections 4.5-4.6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins A. What's the relative risk? A method to directly estimate risk ratios in cohort studies of common outcomes. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:452–454. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breisacher B, Stuart B, Doshi J, Kamal-Bahl S, Shea D. [accessed on December 20, 2007];Medicare’s disabled beneficiaries: The forgotten population in the debate over drug benefits. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/briesacher_disabled.pdf?section=4039.

- 34.Crystal S, Johnson RW, Harman J, Sambamoorthi U, Kumar R. Out-of-pocket health care costs among older Americans. J Gerontol Series B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000 Jan;55:S51–S62. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.1.s51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenberg NE, Kim H, Edwards W, Fleming ST. Burden of common multiple-morbidity constellations on out-of-pocket medical expenditures among older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:423–437. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank RG, Newhouse JP. Mending the Medicare prescription drug benefit: Improving consumer choices and restructuring purchasing. The Brooking Institute; 2007. [accessed on December 20, 2007]. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2007/04useconomics_frank.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soumerai SB. Benefits and risks of increasing restrictions on access to costly drugs in Medicaid. Health Aff. 2004;23:135–146. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson K, Brown ME, Lurie N. Hunger in an adult patient population. JAMA. 1998;279:1211–1214. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kersey MA, Beran MS, McGovern PG, Biros MH, Lurie N. The prevalence and effects of hunger in an emergency department patient population. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1999;6L:1109–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed December 6, 2007];Early Experiences of Medicare Beneficiaries in Prescription Drug Plans. 2006 Aug; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7552.pdf.

- 41.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed December 19, 2007];The Transition of Dual Eligibles to Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage: State Actions During Implementation. 2006 Feb; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7467.pdf.

- 42.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed December 19, 2007];Voices of Beneficiaries: Early Experiences with the Medicare Drug Benefit. 2006 Apr; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7504.pdf.

- 43.Levkoff SE, Cleary PD, Wetle T, Besdine RW. Illness behavior in the aged. Implications for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:622–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb06158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fried LP, Storer DJ, King DE, Lodder F. Diagnosis of illness presentation in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poisal JA. Reporting of drug expenditures in the MCBS. Health Care Financing Review Winter. 2003–2004;25:23–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas CP, Wallack SS, Martin TC. How do seniors use their prescription drug discount cards? Health Aff April. 2005;19:W5-180–W5-190. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.180. (web exclusive) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chisholm MA, DiPiro JT. Pharmaceutical manufacturer assistance programs. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:780–784. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Henry J.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed March 6, 2008];Prescription Drug Trends Fact Sheet. 2005 Nov; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/3057-04.pdf.

- 49.Smith C, Cowan C, Heffler S, Catlin A the National Health Accounts Team. National health spending in 2004: Recent slowdown led by prescription drug spending. Health Aff. 2006;25:186–196. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The Health and Retirement Study. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; [accessed 03 March 2008]. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/ [Google Scholar]