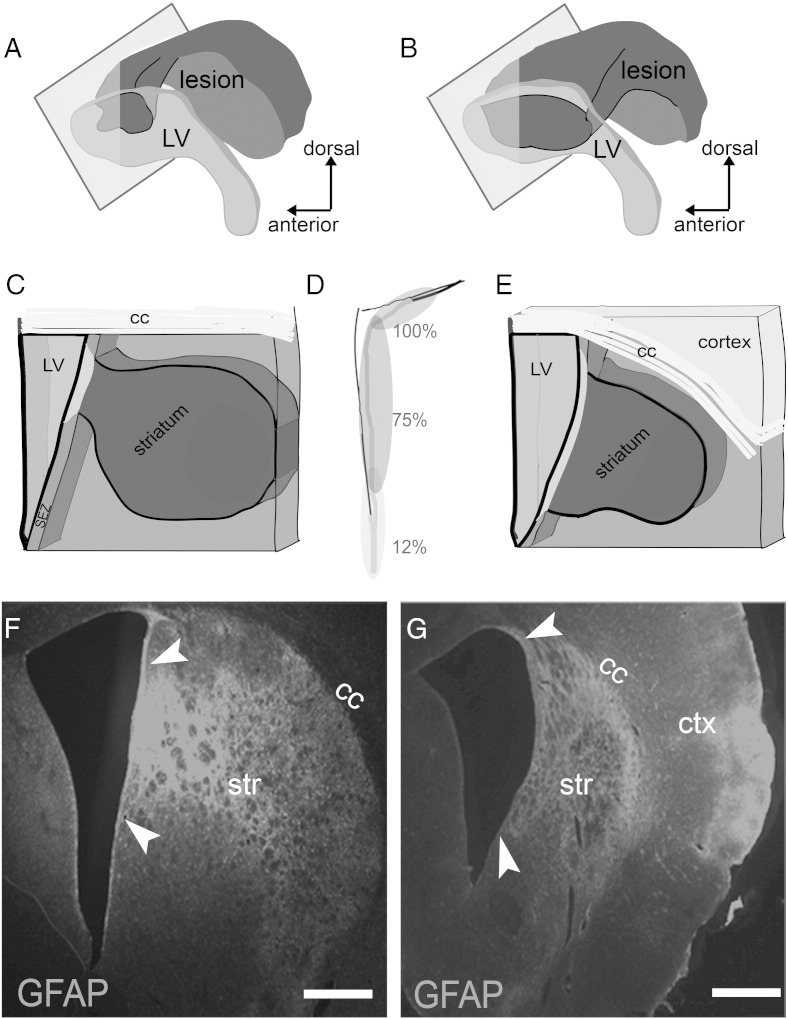

Fig. 2.

Anatomy of the lesion and of its connection with the SEZ. (Panels A–B) Illustrations summarizing results from all animals, showing the striatal lesion (dark grey) and its expansion towards the lateral walls of the lateral ventricle (the ventricle depicted in light grey). In (A) the case of a rat killed 5 weeks after ischaemia is illustrated. This was the case with the minimal observed damage to the SEZ. In (B) the case of a rat killed 1 year after ischaemia is illustrated. This was the case with the maximal observed damage to the SEZ. (Panels C and E) Illustrations of thick coronal sections showing the anatomy of the lesion in relation to the SEZ; the panels correspond to (A) and (B), respectively, in which the plane of the section is depicted as a rectangle. (D) Schematic illustration of the lateral ventricle in which the average percentage of inclusion of part or the whole of different areas of the SEZ in the ischaemic lesion is shown. Note that the dorsal part was always directly affected by ischaemia (100%), the ventral part in few cases (12%). (Panels F, G) Microphotographs of thick coronal sections of rat brains after ischaemia, in which increased GFAP immunostaining is shown to delineate the lesion (the affected part of the SEZ is highlighted by arrowheads). Note the extensive tissue loss in the striatum in (G) (the size of the striatum is less than half of that in (F)) and the expansion of the infarcted area in the cortex. The corpus callosum (cc) seems to be more resistant to degeneration. [Scale bar: 500 μm].