Abstract

Human utilization of the mulberry–silkworm interaction started at least 5,000 years ago and greatly influenced world history through the Silk Road. Complementing the silkworm genome sequence, here we describe the genome of a mulberry species Morus notabilis. In the 330-Mb genome assembly, we identify 128 Mb of repetitive sequences and 29,338 genes, 60.8% of which are supported by transcriptome sequencing. Mulberry gene sequences appear to evolve ~3 times faster than other Rosales, perhaps facilitating the species’ spread worldwide. The mulberry tree is among a few eudicots but several Rosales that have not preserved genome duplications in more than 100 million years; however, a neopolyploid series found in the mulberry tree and several others suggest that new duplications may confer benefits. Five predicted mulberry miRNAs are found in the haemolymph and silk glands of the silkworm, suggesting interactions at molecular levels in the plant–herbivore relationship. The identification and analyses of mulberry genes involved in diversifying selection, resistance and protease inhibitor expressed in the laticifers will accelerate the improvement of mulberry plants.

Mulberry trees are the primary food source for silkworms, which are reared for the production of silk. In this study, He et al. present the draft genome sequence of Morus notabilis and find that it evolved significantly faster than other plants in the Rosales order.

Mulberry trees are the primary food source for silkworms, which are reared for the production of silk. In this study, He et al. present the draft genome sequence of Morus notabilis and find that it evolved significantly faster than other plants in the Rosales order.

Mulberry is a deciduous tree and is an economically important food crop for the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori. The practice of producing valuable silk from silkworms nourished by mulberry leaves started at least 5,000 years ago1 and helped to shape world history through the Silk Road.

The family Moraceae comprises 37 genera with ~1,100 species, including well-known plants such as mulberry, breadfruit, fig, banyan and upas2. Mulberry belongs to the genus Morus with 10–13 recognized species and over a 1,000 cultivated varieties3, which are widely planted in the Eurasian continent, Africa and the United States. Mulberry leaf production for silkworm uses ~626,000 and 280,000 hectares of land in China and India, respectively4. Mulberry also attracts farmers for its delicious fruit, bark for paper production and multiple usages in traditional oriental medicine5,6.

B. mori, a lepidopteran model system and a specialist, feeds on mulberry leaves. The majority of known Lepidoptera species are herbivorous and are, therefore, economically important as major pests of agriculture and forestry. The adoption of silkworm rearing has led to intensive studies on feeding stimulants that are critical to the understanding of plant–insect interactions. The genome sequencing of silkworm was completed in 2008 (refs 7, 8). However, very little genomic information is available for species in the genus Morus. Although the genomic sequence of mulberry will facilitate the improvement of mulberry plants, the mulberry–silkworm genome pair will deepen our understanding of the fundamentals in plant–herbivore adaptation.

Here we report the draft genome sequence of a mulberry species (M. notabilis). The estimated 357-Mb genome of M. notabilis, composed of 7 chromosome pairs, is sequenced using Illumina technology to a 236-fold depth coverage. On the basis of the 330-Mb assembly genome, we identify 128 Mb repetitive sequences and 29,338 protein-coding genes. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that mulberry evolved more rapidly than other sequenced Rosales. The identification and analyses of mulberry genes involved in resistance will accelerate the improvement of mulberry plants. The presence of predicted mulberry micro RNAs (miRNAs) in two tissues of the silkworm suggest probable interactions at molecular levels between the plant–herbivore pair.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

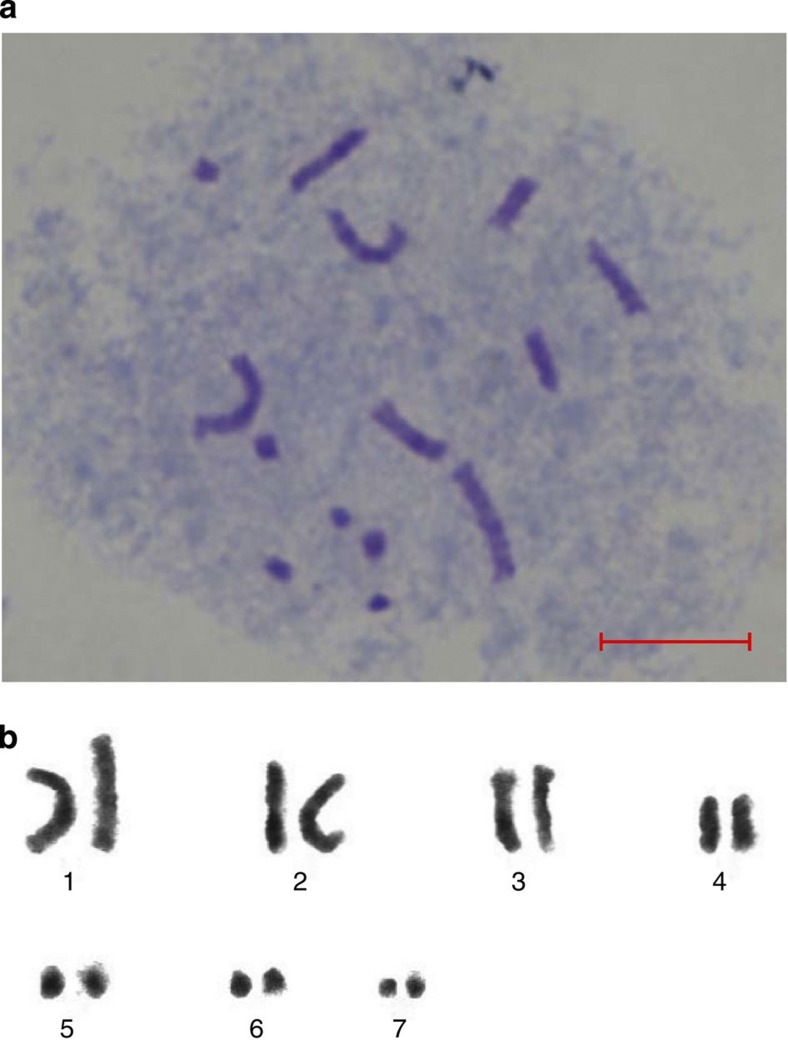

We applied a whole-genome shotgun sequencing strategy to the mulberry species M. notabilis, which contains seven distinct pairs of chromosomes in their somatic cells (Fig. 1). A total of 78.34 billion high-quality bases (236-fold genome coverage) were assembled into a 330.79-Mb mulberry genome with a scaffold N50 length of 390,115 bp and contig N50 length of 34,476 bp (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). There were 16,281 kb (4.9%) gaps and 314,510 kb (95.1%) non-gapped continuous sequences in the final assembly. We selected 10.46 Gb high-quality sequenced short reads from the library with an average insert size of 500 bp to calculate the distribution of K-mer depth, defined as 17 bp here. A total of 8,577,674,309 17-mer were obtained and the genome size of M. notabilis was determined to be 357.4 Mb (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S3). Over 80% of the assembly was represented by 681 scaffolds and the largest scaffold was 3,477,367 bp, with 93.96% of bases covered by more than 20 reads (Supplementary Fig. S2) and 97% of 10,000 random expressed sequence tags (ESTs) more than 90% covered by a scaffold (Supplementary Table S4). The 35.02% GC content of the mulberry genome is similar to that of other eudicots (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 1. Cytological analysis of M. notabilis chromosomes.

(a) Cytological detection of M. notabilis chromosomes. (b) Chromosome karyotyping of M. notabilis. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Table 1. Global statistics of the M. notabilis genome sequencing and assembly.

| Assembling processing | Insert size (bp) | Read length (bp) | Raw data (MB) | Effective data (MB) | Sequence coverage | N50*(bp) | Total length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig and scaffold | 170–800 | 100 | 76,884.40 | 54,625.60 | 165.14 | 5,719 | 280,787,257 |

| Scaffold | 2,000–20,000 | 49 | 49,803.50 | 23,713.73 | 71.69 | 394,221 | 332,102,025 |

| Gap-closure | 170–800 | 100 | 76,884.40 | 54,625.60 | — | — | — |

| Final result | — | — | 126,687.90 | 78,339.33 | 236.82 | 390,115 | 330,791,087 |

*N50 refers to the size above which half of the total length of the sequence is found.

Repetitive sequences

A combination of both de novo repeat prediction and homology-based search against the Repbase library (v15.02) resulted in 127.98 Mb repetitive sequences in the non-gapped mulberry genome (Supplementary Table S5). The transposable element (TE) content in the mulberry genome was probably underestimated because of the inherent limitations of de novo sequencing in dealing with repetitive sequences. After the exclusion of ‘N’s, according to the average coverage depth and the total reads mapped to the repetitive-sequence (~127.7 MB) and non-repetitive-sequence regions (~166.0 Mb) in the mulberry genome, we estimated that there are about 18.48 Mb repetitive sequences in the unassembled sequences. Hence, up to ~47% of the mulberry genome is composed of repetitive sequences. The proportion of repetitive sequences in the mulberry genome is comparable with that in apple (42%), whereas it is slightly higher than that in poplar (35%). More than 50% of mulberry repetitive sequences could be clearly classified into known categories, such as Gypsy-like (6.58%) and Copia-like (6.84%) long-terminal repeat retrotransposons. About 99.11% of TEs had a >10% divergence rate, indicating that most mulberry TEs are relatively ancient (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Gene prediction and functional annotation

We identified 27,085 high-confidence protein-coding loci with complete gene structures in the mulberry genome, using 21 Gb RNA-seq data from five tissues and 5,833 unique ESTs for gene model prediction and validation (Supplementary Method and Supplementary Table S6). Of the 27,085 predicted genes, 99.93% were supported by de novo gene prediction, 58.38% (15,811 genes) by RNA-seq/EST and 69.94% (18,943 genes) by homology-based approaches. More than half (52.19%) of the genes were supported by all three methods. Including 2,253 partial genes annotated by RNA-seq data and ESTs (Supplementary Table S7), we predicted 29,338 genes with an average mRNA length of 2,849 bp, an average coding gene length of 1,156 bp and a mean number of 4.6 exons per gene (Supplementary Table S8). Of these genes, 60.8% were supported by RNA-seq data and 76.92% (22,566/29,338) had homologous targets in functional databases, such as the NCBI non-redundant protein, Swissprot, InterPro, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) and COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups; Supplementary Table S9).

On the basis of the RNA-seq data, we calculated the tissue specificity index τ, to screen for tissue-specific genes and housekeeping genes. We found that 241, 213, 285, 360 and 404 genes specifically expressed in the root, bark, winter bud, male flower and leaf, respectively. In comparison, 1,805 genes were expressed constitutively in the 5 tissue/organs, including 116 encoding ribosomal proteins and 26 encoding translation initiation factors (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Genome evolution

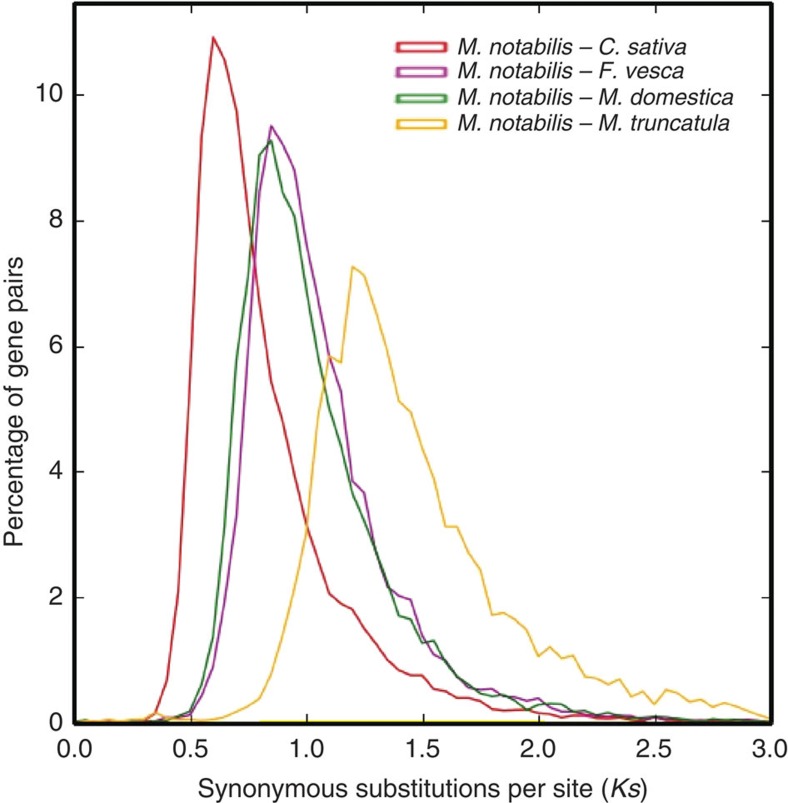

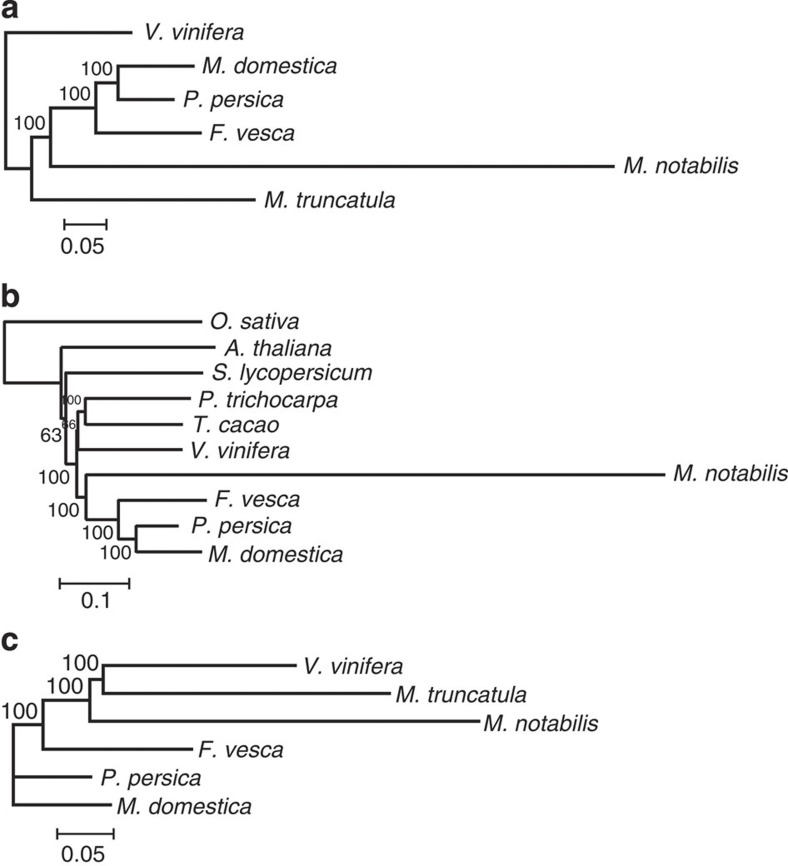

Comparison of the mulberry genome to a rich collection of Rosales genome sequences, including Cannabis sativa9, Malus domestica10 and Fragaria vesca11, offers insights into levels and patterns of DNA-level diversity in this important clade. A phylogenetic tree based on single-copy mulberry genes and other 12 sequenced plants (Fig. 2) supports Moraceae as one of the closest relatives of Rosaceae12,13. The results suggest the speciation times of 63.5 million years ago (mya) for mulberry and C. sativa (Cannabaceae), 88.2 mya for mulberry and apple/strawberry (Rosaceae), and 101.6 mya for mulberry and Medicago truncatula (Fabales)14. Ks plots suggest that mulberry (Moraceae) and C. sativa diverged later than the divergence of apple and strawberry in the Rosaceae family (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships of 13 plant species.

The species are: M. notabilis, T. cacao, A. thaliana, P. trichocarpa, S. lycopersicum, V. vinifera, P. bretschneideri, M. domestica, P. persica, F. vesca, C. sativa, M. truncatula and O. sativa. The scale bar indicates 7.5 million years. The values at the branch points indicated the estimates of divergence time (mya) with a 95% credibility interval.

Figure 3. Ks distribution plot.

The red, magenta, green and yellow lines represent Ks distribution of orthologous gene pairs in M. notabilis–C. sativa, M. notabilis–F. vesca, M. notabilis–M. domestica and M. notabilis–M. truncatula, respectively.

Different gene groups of several plants were then used to construct three phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4). First, we used single-copy genes in the predicted mulberry gene data sets and their best-matched ones in other species to reconstruct phylogeny (Fig. 4a). Second, we used single-copy genes of genewise-predicted mulberry genes to reconstruct phylogeny (Fig. 4b). Third, we used best-matched genes in collinear positions across different genomes to reconstruct phylogeny (Fig. 4c). In all of the reconstructed phylogenetic trees, the branch of mulberry is longer than those of the other species, suggesting that mulberry evolved much (~3 times) faster than other Rosales.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic trees of M. notabilis and other plants.

Different data set were used to construct a phylogeny of the considered species. (a) A tree constructed using 136 single genes in the predicted M. notabilis gene data sets and their best-matched ones. (b) A tree constructed using 62 single genes predicted by Genewise in 10 plants. (c) A tree constructed using 318 best-matched collinear genes across 6 plant genomes. The scale of a unit is shown below each tree and the number on it shows how many amino acid substitutions per sites.

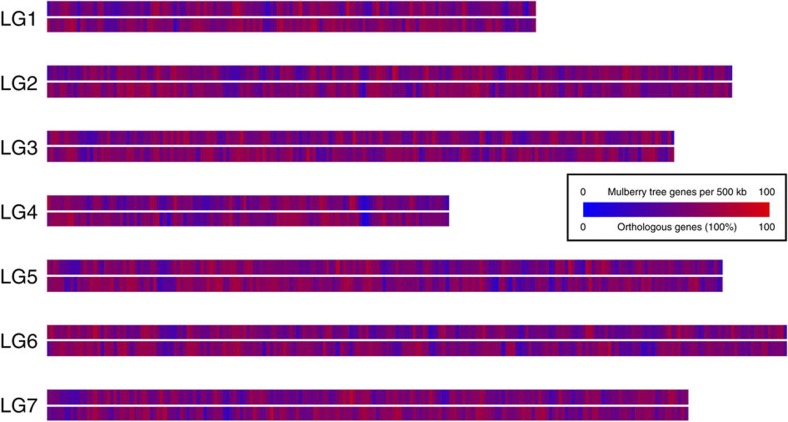

To investigate the syntenic and evolutionary relationship of the mulberry genome, without any available genetic map, in-silico gene staining or genome zipper approach was performed against the strawberry (F. vesca) genome sequences15. The gene density distribution of the conserved syntenic regions against strawberry was computed and visualized as a heatmap using a sliding window approach (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 1).

Figure 5. In-silico staining of M. notabilis gene models against F. vesca.

Using a sliding window approach (500 kb), the total gene density (upper track) and the relative distribution of orthologous genes (lower track) were calculated for M. notabilis.

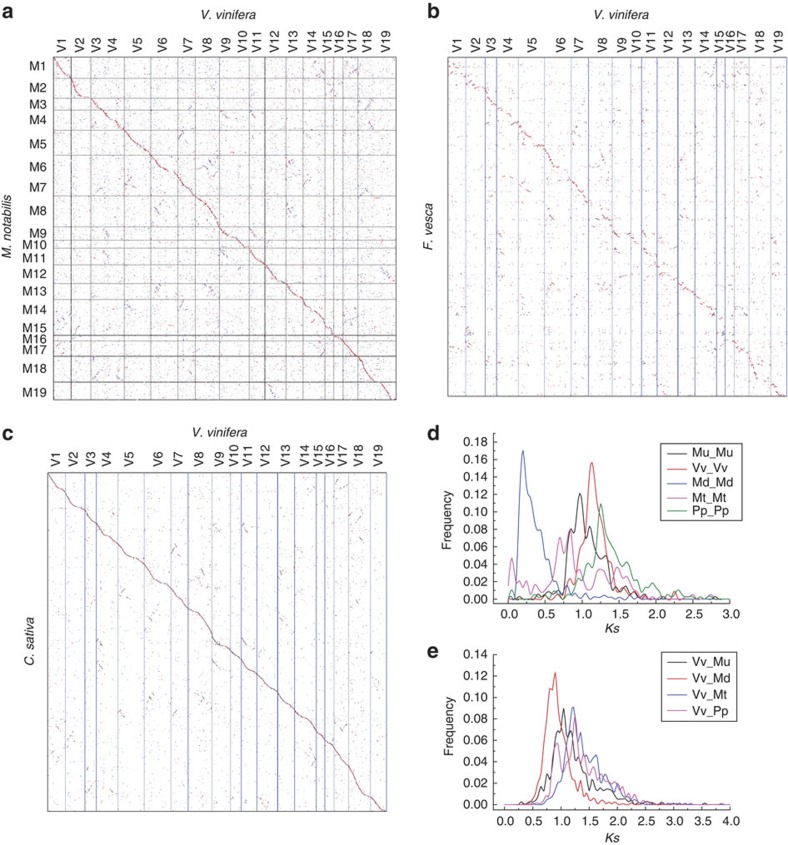

Alignment of mulberry scaffolds to their best-matched grape chromosomal regions (Fig. 6a) often revealed two additional but less pronounced homologous regions, indicating that mulberry shares the eudicot-common triplication revealed initially by the analysis of the grape genome16. Similarly, a region of the strawberry or cannabis genomes often has one primary and two secondary homologous grape genome regions (Fig. 6b,c), contrary to an earlier report of no paleopolypoidization in strawberry11. The fact that mulberry, strawberry and cannabis have the pan-eudicot hexaploidization as their most recent polyploidy is further supported by the distribution of synonymous nucleotide substitution rates of homologous genes in collinear blocks within and between these genomes (Fig. 6d,e).

Figure 6. Dotplots of species and Ks distributions.

M. notabilis–V. vinifera (a), F. vesca–V. vinifera (b), C. sativa–V. vinifera (c) and Ks distribution of within-each-plant homologues (d) and between-different-plant homologues (e) in collinearity. For M. notabilis and C. sativa, gene coding DNA sequences of V. vinifera were searched against their genomes by using BLASTN, and their hit locations were found. This BLASTN information was used to produce the dotplots. Unanchored scaffolds were linked together as to their best-matched grape genomic regions, and the putative pseudochromosomal regions of M. notabilis and C. sativa genomes were produced. For F. vesca, protein–protein searches using BLASTP were conducted to reveal putative homologous genes, and this information was used to make dotplot; along chromosomes, genes were placed with their chromosomal order as coordinates.

Diversifying selection

The divergent morphologies and phytochemistries for which various Rosales are cultivated may reflect diversifying selections on orthologous genes. By regression analysis between the ω, the non-synonymous (Ka) versus synonymous (Ks) nucleotide substitution rate ratio (Ka/Ks) and the Ks values, we estimated that 307, 338, 353 and 197 gene pairs have significantly higher-than-average non-synonymous (Ka) versus synonymous (Ks) nucleotide substitution rate ratios (ω), indicating diversifying selection for M. notabilis–C. sativa, M. notabilis–F. vesca, M. notabilis–M. domestica and M. notabilis–M. truncatula (Supplementary Data 2). Interestingly, for the subset of genes that meet the more stringent Fisher’s exact test, diversifying selection between 222 pairs of M. notabilis–C. sativa genes (Supplementary Fig. S6 and Supplementary Table S10) is enriched in aging and stress response-related genes, perhaps linked to the difference in life expectancy of the plants. In M. notabilis–F. vesca and M. notabilis–M. domestica comparisons, 228 and 258 diversifying selected orthologous pairs (Supplementary Data 2) may be associated with functional differences, for example, Morus000754 (mulberry)–MDP0000252168 (apple) and Morus009486 (mulberry)–MDP0000290357 (apple) involved in cutin biosynthetic processes may be related to the apple’s thick cuticle (although mechanisms of cuticle biogenesis are not clear17). Particularly prominent in the mulberry–Rosaceae (apple, strawberry) diversification are the gene pairs related to plastid components (Supplementary Data 3 and 4), suggesting that Rubisco18 and many plastid genes were under positive diversifying selection.

Resistance genes

The mulberry genome has 142 nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-containing resistance (R) genes that constitute about 0.53% of all Morus genes, comparable to that of Arabidopsis (0.52%) and strawberry (0.58%), and lower than that of poplar (0.86%) and apple (1.49%) (Supplementary Data 5 and Supplementary Table S11). All of these R genes were classified into six groups, TIR-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS-LRR, NBS-LRR, NBS, CC-NBS and TIR-NBS, with the maximum number of 46 belonging to the CC-NBS-LRR group. The Morus genome contains 127 cysteine protease (CP; 0.47%) and 129 aspartic protease (AP; 0.48%) encoding genes, which is comparable to that of apple (0.59%, 0.37%) and of strawberry (0.49%, 0.53%; Supplementary Data 6 and 7, and Supplementary Table S12). Prominent among these are 13 CP and 4 AP genes expressed in the laticifers of mulberry (Supplementary Table S13). Interestingly, one of the four AP genes (Morus008067) is under diversifying selection with an apple gene (MDP0000201076; Supplementary Data 2).

Protease inhibitor genes

To alleviate insect infestation, plants have evolved a defence mechanism to interfere with the digestive systems of insects by expressing a number of plant protease inhibitors (PIs). On the basis of the known PI sequences and their conserved domains, we identified 79 PIs in the mulberry genome (Supplementary Table S14). Twenty-two family C1 cysteine peptidase inhibitor genes and 19 family A1/C1 serine peptidase inhibitor genes were annotated in the Morus genome, accounting for half of the identified inhibitor genes.

Mulberry miRNAs identified in silkworm tissues

Adaptation of silkworm to the seasonal growth of mulberry leaves may involve cross-kingdom molecular signalling. By aligning the Morus genome to various plant small RNA databases, we predicted 311 small nuclear RNAs and 223 miRNAs (Supplementary Table S15). Five of the mulberry miRNAs, absent in the silkworm genome, were found in the miRNA database derived from silkworm larval haemolymph (two), anterior-middle silk glands (two), and posterior silk glands (one) (Supplementary Table S16). The sequencing of small RNAs was repeated using a different batch of silkworm haemolymph. The presence of the mulberry miRNAs in silkworm haemolymph identified in an earlier database was confirmed in the repeat experiment.

Discussion

Early studies proposed a basic chromosome number of 14 for mulberry species19. This number is widely cited in the literature even though later cytological studies on two M. indica species proposed a basic chromosome number of 7 for Morus species20. The diverse levels of polyploidization in the genus are reflected in the wide range of chromosome numbers: 14 in M. notabilis21, 28 in M. indica or M. alba, 42 in M. bombycis and even 308 in M. nigra22. Because of the high complexity of polyploid genomes, the species (M. notabilis) with 14 chromosomes is chosen for whole-genome sequencing. To verify the number of chromosomes of the M. notabilis, somatic cells at metaphase stage in the apical bud was used for cytological analyses. We confirmed that the cells of M. notabilis contained 14 chromosomes. Chromosome karyotyping clearly grouped the 14 chromosomes of M. notabilis into seven distinct pairs, supporting the basic chromosome number of seven proposed in the studies on M. indica20.

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the mulberry genes form a clade with those of other Rosales. Moraceae, conventionally considered as belonging to Urticales, is thought to be one of the closest relatives of Rosaceae. However, a recent report suggested that the families Ulmaceae, Cannabaceae, Moraceae and Urticaceae belong to a single clade23, named as the urticalean rosids24. Moraceae was later classified into Rosales by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group III13. Our results support this reclassification.

Mulberry is rapidly evolving at the nucleotide level. It’s fast evolving genes may have contributed to the flexibility of mulberry to adapt to environments outside of its native range, facilitating its spread to Europe, Africa and the United States. In contrast to its rapid nucleotide changes, Rosales ploidies have evolved conservatively. Mulberry, strawberry, cannabis, papaya and grape underwent the most recent pan-eudicot hexaploidization. Widespread neopolyploidy in mulberry with up to 308 (44 × ) chromosomes22 and strawberry with up to 70, suggest an intriguing scenario that these lineages may be receptive to the benefits of a new wave of polyploidization.

Mulberry is a woody perennial tree and constant pruning is a common practice not only to collect leaves for silkworms but also to boost leaf production. Pruning increases risk of pest infestation and pathogen infection; therefore, a robust defence system helps to fend off these biotic stresses. Proteins encoded by plant R genes allow the recognition of pathogen effectors, such as their cognate avirulence gene products25. Most of the extensively studied plant R genes are NBS-containing R genes26. In the mulberry genome, we identified a total of 142 NBS-containing R genes. Mulberry is a lactiferous plant and protein components, such as the chitinase-like protein, in mulberry latexes are believed to be involved in the defence system against microbes or herbivores27,28,29. Cysteine proteases in the laticifers of papaya and aspartic proteases secreted into the pitcher of Nepenthes alata30,31 have also been shown to be toxic to herbivorous insects. Sequencing of mulberry genome revealed 127 CP genes and 129 aspartic protease genes. The functional studies of these genes will expand our knowledge on mulberry defence mechanisms.

It remains unclear how the oligophagous silkworm bypasses plant defence mechanisms that interfere with insect digestive systems. In particular, plant PIs reduce the activity of the digestive enzymes in the guts of herbivorous insects, resulting in serious developmental malformations, lethality and reduced procreation32,33. Previous studies reported that plants produce more PIs with multidomains and multimeric structures, which have antinutritional effects on Spodoptera frugiperda34. The insect circumvents plant PIs via inducible PI-insensitive proteases and the degradation of plant PIs by specific proteases35,36. The diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, a notorious Lepidopteran pest of cruciferous crops, inactivates mustard trypsin inhibitor 2 to break through host plant defence37. Parallel transcriptome analysis of the silkworm–mulberry oligophagy, benefiting from the respective genome sequences may accelerate our understanding of the fundamentals in plant–herbivore adaptation.

A total of five mulberry miRNAs were found in the silkworm sequencing data. None of them seem to come from the silkworm genome. One of them, MIR156, is abundantly expressed in the old leaves at the vegetative growth stage of rice and has a major role in the juvenile-to-adult transition in plants38,39,40. Noting that rice MIR168a can be transferred to human and regulate the low-density lipoprotein receptor adaptor protein 1 (ref. 41), it remains unclear whether mulberry MIR156 in silkgland signals leaf aging and stimulates cocoon spinning, or whether tissue-specific presence of other mulberry MIRs has a role in coordinating development of silkworm.

In summary, genomic information is an important resource for modern genetic research of mulberry. The genomic features of mulberry, such as gene families, segmental duplication, and syntenic blocks not only enrich the data available for plant comparative genomics but also accelerate future identification of target genes from closely related species of the family Moraceae. Genetic markers can be developed based on these genome sequences for studies involving genetic map construction, positional cloning, strain identification and marker-assisted selection. These molecular tools and genomic techniques will accelerate agricultural improvement. As a model system for studies of plant–herbivore relationships, the availability of the mulberry and silkworm genome sequences offers a unique opportunity to gain insights into such biological partnerships prevalent in most terrestrial habitats.

Methods

Karyotype analysis of M. notabilis C.K. Schn

Young leaves were treated with 2 mM 8-hydroxy-quinoline for 3 h at room temperature, and then fixed in 3:1 methanol/glacial acetic acid for 2 h at 4 °C. Fixed leaves were incubated with 1/15 M KCl solution for 30 min and digested by 2.5% (W/V) cellulose (YaKult Co., Japan) and 2.5% (W/V) pectolyase (YaKult Co.) for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Digested leaves were treated with ddH2O for 10 min and post-fixed in 3:1 methanol/glacial acetic acid for 30 min at room temperature. Post-fixed leaves were smashed and two drops of cell suspension were added on a glass slide for Giemsa staining at room temperature for 6 h. Slides were analysed under a microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

DNA and RNA preparation

A wild mulberry species, M. notabilis, with a chromosome number of 14 was used for genome sequencing. Genomic DNA used as a template for the library construction was extracted from the winter buds by a CTAB method. Total RNA was isolated from five tissues (root; 1-year-old branch bark; winter bud; male flower; leaf) according to the methods of Wan and Wilkins42, and was treated with RNase-free DNase I for 30 min at 37 °C (New England BioLabs) to remove residual DNA. Beads with oligo(dT) were used to isolate poly(A) mRNA. First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers and reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase I (New England BioLabs) in the presence of RNase H (Invitrogen).

Genome sequencing

A whole-genome shotgun approach was used to sequence the mulberry genome. Sequencing libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA). For short-insert DNA libraries, 5 μg of genomic DNA was fragmented by nebulization with compressed nitrogen gas. The DNA ends were blunted with an ‘A’ base to the ends of the DNA fragments. Next, the DNA adaptors (Illumina) with a single ‘T’ base overhang at the 3′-end were ligated to the DNA fragment. We then purified the ligation products on a 2% agarose gel, and excised and purified gel slices for each insert size (Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit). For long (≥2 Kb), mate-paired libraries, 10–30 μg genomic DNA was fragmented by nebulization with compressed nitrogen gas. We then used biotin-labelled dNTPs for polishing and gel selection for the main bands of 2, 5 and 10 Kb. The DNA fragments were then circularized for self-ligation. The two ends of the DNA fragment were merged together and the linear DNA fragments were digested by DNA exonuclease. The circularized DNA was fragmented again, followed by enrichment of the ‘merged ends’ with magnetic beads using biotin and streptavidin interaction, then the ends were blunted, and ‘A’ base and adaptors were added. We followed the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina) for paired-end (PE) sequencing runs by the following workflow: cluster generation, template hybridization, isothermal amplification, linearization, blocking, denaturing and hybridization of sequencing primers. The base-calling pipeline (SolexaPipeline-0.3) was used to obtain sequences from the raw fluorescent images.

Genome assembly

Before de novo assembly, we filtered the low-quality data by the following five steps: (1) trim the low-quality bases on both 5′- and 3′-end of each read according to quality reports from Hiseq2000 pipeline; (2) discard those reads with Ns>10% of the read length; (3) remove those reads when the total low-quality bases (Q<8) was >50% of the read length; (4) discard the reads contaminated by adapters; and (5) remove duplicated reads caused by PCR during library construction. SOAPdenovo is a genome assembler developed in BGI-Shenzhen and this software preformed de Bruijn graph algorithm assemblies in a stepwise strategy43. We first assembled short reads from fragmented small insert-size (<1 kb) libraries into contigs using 49-kmers. We then realigned all the reads to contig sequences with 41-kmers and compiled all aligned reads to the available contigs. According to the PE information, we joined the contigs into scaffolds by seven steps from 170 bp insert-size libraries to 20 kb insert-size libraries. To fill the gaps in scaffolds, we collected the PE reads, one of which uniquely aligned to a contig and the other located in gaps, to repeat a local assembly. The intra-scaffold gaps were filled by local assembly using the reads from a read pair with one end uniquely aligned to a contig and the other in a gap.

TEs and repetitive DNA

To predict the TEs in the mulberry genome, we first constructed a TE library with RepeatModeler (version 1.0.3, http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html), RepeatScout44 (version 1.0.5, http://bix.ucsd.edu/repeatscout/) and Piler45 (version 1.0, http://www.drive5.com/piler/), and then performed de novo prediction of TEs on it using RepeatMasker (version 3.2.9, http://www.repeatmasker.org/)46. RepeatMasker and ProteinMask (version 3.0) were also used to find known TEs with a TE library composed of Repbase47 (version 15.02, http://www.girinst.org/repbase/) and eudicot TEs from TIGR (version 3.0, http://plantta.jcvi.org)48. Tandem Repeats Finder (version 4.04, http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html) was used to identify tandem repeats. Simple repeats, satellite sequences and low-complexity repeats were identified by RepeatMasker with the option of ‘-noint’49. The classified TE families in the M. notabilis genome were aligned to the consensus sequences in the Repbase library (v15.02) and the sequence divergence rates of TEs were determined.

Gene prediction and annotation

Three methods were used to predict the mulberry genes: a homology-based method, a de novo method and an EST/transcript-based method. High-confidence set of genes were predicted by both homology-based and de novo methods. For the annotation of the mulberry protein-coding genes, we searched the nucleotide sequences of 27,085 high-confidence genes against NCBI, KEGG, COG and Swissport databases with a minimal e-value of 1e−5. Protein domains and functions of predicted 27,085 amino acid sequences of mulberry were annotated with Iprscan (v4.4.1).

RNA-seq and EST sequencing

The cDNA libraries were prepared and sequenced according to Illumina’s protocols. TopHat (v1.3.3) was used to align these RNA-seq reads to the mulberry genome. The reads per kb per million reads values were calculated to measure the gene expression levels of the five tissues, and the tissue specificity index τ was computed to identify the specific expressed genes in each tissue. For EST sequencing, RNA samples from the same five tissues were combined for cDNA synthesis using Creator SMART cDNA Kit (Clontech). A normalized cDNA library was constructed with Trimmer-Director kit (Evrogen). Ten thousand randomly chosen clones from the normalized library were sequenced using ABI3730 (Applied Biosystem).

Non-coding RNA genes

The transfer RNAs in the M. notabilis genome were found using tRNAscan-SE (v1.23) with the ‘eukaryotes’ option50. The M. notabilis genome was aligned to plant ribosomal RNAs with BLASTN (e-value, 1e−5), and rRNAs with sequence identity >85% and heat shock protein length longer than 50 bp were recorded. The M. notabilis genome was aligned to the Rfam database (v 9.1) with BLASTN (e-value, 1). The raw output was further analysed by the INFERNAL software, which was used to predict miRNA and small nuclear RNA by searching DNA sequence databases owing to the RNA structure and sequence similarities.

In-silico gene staining

We used BLASTP (e-value, 1e−5) to identify reciprocal best-hit orthologous gene pairs between mulberry and strawberry. This reciprocal best-hit matrix and the orthologous gene pairs were used to further define the syntenic blocks between two species in the MCscan pipeline. The scaffolds of mulberry with syntenic blocks were aligned together according to the syntenic order in the strawberry linkage groups using Genome Zipper15. The distributions of gene density and orthologous gene density were calculated using a 500-kb sliding window approach.

Identification of mulberry miRNAs in silkworm tissues

The small RNA was extracted from 12 ml of silkworm haemolymph (collected from the fifth instar day-5 larvae) using mirVana PARIS kit (Ambion, USA). The sequencing of small RNA in haemolymph was conducted following the procedure describe by Liu51. The sequences of small RNA in the anterior-middle and posterior silk glands were downloaded from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds?term=GSE17965. The small RNA sequenced data of three silkworm tissues were used as queries to search against mulberry-predicted miRNAs by BLASTN without mismatch. The sequences aligned to silkworm genome, rRNAs and tRNAs were filtered out.

Phylogenetic tree and determine the speciation time

Single-copy genes from 13 plant species were used to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree based on the maximum likelihood method. Orthologous gene pairs had been determined by top-ranked BLAST hits in each other with an e-value 1e−10. The Ks value52 between the orthologous pairs were calculated by the yn00 programme in PAML package53. The speciation time base on Ks value was dated by the equation T=Ks/2λ with λ=6.1 × 10−9 (ref. 54). Orthologous gene pairs likely to be under positive (diversifying) selection between mulberry and each of the other four plants were determined by regression analysis between Ka and Ks values based on a 95% prediction interval range55. Gene pairs with ω-values greater than the prediction interval upper limit were considered to show evidence of positive selection. Gene Ontology groups in which the high omega pairs were significantly included were determined by BLAST2GO56 with a cut-off P-value<0.05 using Fisher’s exact test.

Inference of gene collinearity

We inferred gene collinearity with MCSCAN57, a multiple-chromosome alignment tool, complemented by analyses using COLINEARSCAN58, a pairwise-chromosome alignment tool. The inferred collinear genes were used to perform phylogenetic and evolutionary analyses.

Dating evolutionary event

We used collinear genes between plants, and within-each-plant homologues with high confidence, to infer evolutionary events. For example, collinear genes between mulberry scaffolds are likely to have resulted from ancient polyploidization event(s) if present; and collinear genes between mulberry and grape are likely to have resulted from a divergence of the two species. The synonymous nucleotide substitution rates (Ks) were calculated by using Nei–Gojobori approach52 implemented in PAML53. The distributions of Ks values were drawn to infer the relative time of evolutionary events.

Homologous dotplotting

We used predicted gene sets that are described above and a gene data set predicted by Genewise59 in the analysis. Genome sequences and annotations of grape, apple, strawberry and cannabis were downloaded from online databases, and the most up-to-date versions till October 2012 were used in the analyses. In comparison with genomes with available pseudochromosomes, we used protein–protein searches using BLASTP to reveal putative homologous genes, and the output was used to make dotplot; genes were placed along with their chromosomal order as coordinates. When a comparison was done involving genomes (for example, cannabis and mulberry) without available pseudochromosomes, that is, those with unanchored scaffolds, gene coding DNA sequences from a genome sequences with pseudochromosomes (for example, grape) were searched against the cannabis and mulberry genomes using BLASTN, and hits on the pseudochromosomes were located. The BLASTN output was used to produce dotplots. To detect the genome duplication events, the unanchored scaffolds were linked to their best-matched grape genomic regions on the putative pseudochromosomes. The putative pseudochromosomal regions of mulberry and cannabis were identified this way. A corresponding grape region would have two matched regions clustered together in the dotplot.

Data used in this study

The genome data were downloaded from the following websites and are associated with the accession codes provided.

Arabidopsis thaliana (TAIR9), ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/Genes/TAIR9_genome_release/, GCA_000001735.1.

C. sativa, http://genome.ccbr.utoronto.ca/downloads.html, GCA_000230575.1.

Carica papaya (version 1th), ftp://ftp.jgi-psf.org/pub/compgen/phytozome/v5.0/Cpapaya/, GCA_000150535.1.

Cucumis sativus (version 1th) http://cucumber.genomics.org.cn/page/cucumber/download.jsp, GCA_000004075.1.

F. vesca (version 1.1), http://www.rosaceae.org/species/fragaria/fragaria_vesca/genome_v1.1, GCA_000184155.1.

Glycine max (version 1.0), ftp://ftp.jgi-psf.org/pub/compgen/phytozome/v5.0/Gmax/, GCA_000004515.1.

M. domestica (version 1.0), http://genomics.research.iasma.it/index.html, GCA_000148765.2.

M. truncatula, ftp://ftp.jgi-psf.org/pub/compgen/phytozome/v8.0/Mtruncatula/, GCA_000219495.1.

Populus trichocarpa (version 5.0), ftp://ftp.jgi-psf.org/pub/compgen/phytozome/v5.0/Ptrichocarpa/, GCA_000002775.1.

Prunus persica, ftp://ftp.jgi-psf.org/pub/compgen/phytozome/v8.0/Ppersica/, GCA_000346465.1.

Pyrus bretschneideri, http://peargenome.njau.edu.cn:8004/default.asp?d=1&m=1, GCA_000315295.1.

Theobroma cacao (version 1.0), http://cocoagendb.cirad.fr/gbrowse/download.html, GCA_000403535.1.

Vitis vinifera, http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/Download/Projets/Projet_ML/data/12X/, GCA_000003745.2.

Author contributions

N.H., C.Z., X.Q., Shancen Z. and Y.T. have contributed equally to this paper. N.H., D.J., S.L., M.L., Q.X. and Z.X. coordinated the project; C.Z., Y.T., Shancen Z., C.G. and D.L. performed genome and transcriptome sequencing; Tae-Ho L., Xiyin W., Q.C., R.H., X.T., G.Y., D.L., Jinpeng W. and Tao L. performed evolution analyses; Y.X., N.H. and Xiling W. contributed to the cytological analyses; X.Q., Q.F., Tian L., A.Z., Q.Z., B.M., L.J., J.L., P.S., L.F., J.S., J.Z., C.W., Q.S., Q.W., K.Z. and H.W. analysed the genomic data; M.Y., C.T., Z.W., F.D., J.C., Y.L., Shutang Z., Tianbao L., Shougong Z., Jian W., Junyi W., H.Y., G.Y. and Jun W. made the characteristic analyses of the Morus genome; N.H. and Shancen Z. wrote the paper; N.H., A.P. and G.Y. revised the manuscript.

Additional information

Accession codes: The Morus genome data has been deposited in the Genbank short-read archive (Bioproject: PRJNA202089; short reads: SRA075563). The version described in this paper is ATGF01000000. The miRNA data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession code GSE48168.

How to cite this article: He, N. et al. Draft genome sequence of the mulberry tree Morus notabilis. Nat. Commun. 4:2445 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3445 (2013).

Supplementary Material

The distribution of mulberry gene according to the syntenic order in the strawberry linkage groups using Genome Zipper.

Gene ontology information of orthologous gene pairs determined that were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and each of C. sativa, M. domestica, F. vesca and M. truncatula.

Fisher exact test results of the 228 orthologous pairs, which were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and F. vesca.

Fisher exact test results of the 258 orthologous pairs, which were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and M. domestica.

NBS-containing resistance genes in the M. notabilis genome.

Predicted cysteine proteases in M. notabilis genome.

Predicted aspartic proteases in M. notabilis genome.

Supplementary Figures S1-S6, Supplementary Tables S1-S16 and Supplementary Methods

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by research grants from the National Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China (No. 2013AA100605-3), the ‘111’ Project(B12006), the Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of Chongqing (Grant No. cstc2011jjjq0010), the grant for National Non-profit Research Institutions to Research Institute of Forestry, CAF, earmarked fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System of Zhejiang Province, China, Modern Agriculture Industry Technology System Construction Project (Sericulture), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation Research Team project (No. 9351064001000002), Silkworm and Mulberry Resistance Breeding Center of the State Key Laboratory of Silkworm Genome Biology (No. 2012B090600049) and the Chong Qing Science & Technology Commission (No. cstc2012jjys80001).

References

- Barber E. J. W. Prehistoric Textiles: The Development Of Cloth In The Neolithic And Bronze Ages With Special Reference To The Aegean Princeton University Press (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Clement W. L. & Weiblen G. D. Morphological evolution in the mulberry family (Moraceae). Syst. Bot. 34, 530–552 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Nepal M. P. & Ferguson C. J. Phylogenetics of Morus (Moraceae) inferred from ITS and trnL-trnF sequence data. Syst. Bot. 37, 442–450 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez M. D. World distribution and utilization of mulberry, potential for animal feeding. FAO Electron. Conf. Mulberry Animal Prod. (Morus1-L) 1–11 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y. et al. Antioxidative flavonoids from the leaves of Morus alba. Arch. Pharm. Res. 22, 81–85 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano N., Tomioka E., Kizu H. & Matsui K. Sugars with nitrogen in the ring isolated from the leaves of Morus bombycis. Carbohyd. Res. 253, 235–245 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q. et al. A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 306, 1937 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, I. S. G. The genome of a lepidopteran model insect, the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 1036–1045 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bakel H. et al. The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa. Genome Biol. 12, R102 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco R. et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). Nat. Genet. 42, 833–839 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V. et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat. Genet. 43, 109–116 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. R., Soltis D. E. & Robertson K. R. Systematic and evolutionary implications of rbcL sequence variation in Rosaceae. Am. J. Bot. 81, 890–903 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Chase M. W. et al. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 105–121 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Crepet W. L., Nixon K. C. & Gandolfo M. A. Fossil evidence and phylogeny: the age of major angiosperm clades based on mesofossil and macrofossil evidence from Cretaceous deposits. Am. J. Bot. 91, 1666–1682 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. F. et al. Gene content and virtual gene order of barley chromosome 1H. Plant Physiol. 151, 496–505 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O. et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 449, 463–467 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeats T. H. et al. Mining the surface proteome of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit for proteins associated with cuticle biogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 3759–3771 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov M. V. & Filatov D. A. Widespread positive selection in the photosynthetic Rubisco enzyme. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 73 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janaki Ammal E. The origin of black mulberry. J. R. Hortic. Soc. 73, 117–120 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- Datta M. Cytogenetical studies on two species of Morus. Cytologia (Tokyo) 19, 86–95 (1954). [Google Scholar]

- Yu M. D. et al. The discovery and study on a natural haploid Morus notabilis Schneid. Sci. Sericult. 22, 67–71 (1996) (Chinese writing). [Google Scholar]

- Tojyo I. Studies on the polypolid in mulberry tree (IV) On the flower and pollen grains of one race in Morus nigra L. J. Sericult. Sci. Jpn 35, 360–364 (1966) (Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Soltis D. E., Yang Y., Li D. & Yi T. Multi-gene analysis provides a well-supported phylogeny of Rosales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 60, 21–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytsma K. J. et al. Urticalean rosids: circumscription, rosid ancestry, and phylogenetics based on rbcL, trnL-F, and ndhF sequences. Am. J. Bot. 89, 1531–1546 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield J. W. From bacterial avirulence genes to effector functions via the hrp delivery system: an overview of 25 years of progress in our understanding of plant innate immunity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 721–734 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers B. C., Kaushik S. & Nandety R. S. Evolving disease resistance genes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 129–134 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasano N. et al. A unique latex protein, MLX56, defends mulberry trees from insects. Phytochemistry 70, 880–888 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima S. et al. Two chitinase-like proteins abundantly accumulated in latex of mulberry show insecticidal activity. BMC Biochem. 11, 6 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima S. et al. Comparative study of gene expression and major proteins’ function of laticifers in lignified and unlignified organs of mulberry. Planta 235, 589–601 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K. et al. Papain protects papaya trees from herbivorous insects: role of cysteine proteases in latex. Plant J. 37, 370–378 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An C. I., Fukusaki E. & Kobayashi A. Aspartic proteinases are expressed in pitchers of the carnivorous plant Nepenthes alata Blanco. Planta 214, 661–667 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayés A. et al. Structural basis of the resistance of an insect carboxypeptidase to plant protease inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16602 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Song X., Li G. & Wang P. Midgut cysteine protease-inhibiting activity in Trichoplusia ni protects the peritrophic membrane from degradation by plant cysteine proteases. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 726–734 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekwilder J. & Jongsma M. Co-evolution of insect proteases and plant protease inhibitors. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 12, 437–447 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C., Capella A. N., Sitnik R. & Terra W. R. Properties of the digestive enzymes and the permeability of the peritrophic membrane of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera) larvae. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A 107, 631–640 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Zavala J. A., Giri A. P., Jongsma M. A. & Baldwin I. T. Digestive duet: midgut digestive proteinases of Manduca sexta ingesting Nicotiana attenuata with manipulated trypsin proteinase inhibitor expression. PloS One 3, e2008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Fang Z., Dicke M., Loon J. J. A. & Jongsma M. A. The diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, specifically inactivates Mustard Trypsin Inhibitor 2 (MTI2) to overcome host plant defence. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 55–61 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K. et al. Gradual increase of miR156 regulates temporal expression changes of numerous genes during leaf development in rice. Plant Physiol. 158, 1382–1394 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Czech B. & Weigel D. miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 138, 738–749 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W. et al. miRNA control of vegetative phase change in trees. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002012 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 22, 107–126 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C. Y. & Wilkins T. A. A modified hot borate method significantly enhances the yield of high-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Anal. Biochem. 223, 7–12 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Li Y., Kristiansen K. & Wang J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 24, 713–714 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. L., Jones N. C. & Pevzner P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358 (2005) http://bix.ucsd.edu/repeatscout/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. & Myers E. W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21, i152–i158 (2005) http://www.drive5.com/piler/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A., Hubley R. & Green P. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. URL http://www.repeatmasker.org (2004).

- Jurka J. et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005) http://www.girinst.org/repbase/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea G. et al. TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics 19, 651–652 (2003) http://plantta.jcvi.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M. & Eddy S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 0955 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. et al. MicroRNAs of Bombyx mori identified by Solexa sequencing. BMC Genomics 11, 148 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. & Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3, 418–426 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. & Conery J. S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290, 1151–1155 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S. et al. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz S. et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H. et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 18, 1944–1954 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Statistical inference of chromosomal homology based on gene colinearity and applications to Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 447 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Clamp M. & Durbin R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The distribution of mulberry gene according to the syntenic order in the strawberry linkage groups using Genome Zipper.

Gene ontology information of orthologous gene pairs determined that were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and each of C. sativa, M. domestica, F. vesca and M. truncatula.

Fisher exact test results of the 228 orthologous pairs, which were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and F. vesca.

Fisher exact test results of the 258 orthologous pairs, which were under diversifying selection, between M. notabilis and M. domestica.

NBS-containing resistance genes in the M. notabilis genome.

Predicted cysteine proteases in M. notabilis genome.

Predicted aspartic proteases in M. notabilis genome.

Supplementary Figures S1-S6, Supplementary Tables S1-S16 and Supplementary Methods