Abstract

Src kinase plays an important role in integrin signaling by regulating cytoskeletal organization and cell remodeling. Previous in vivo studies have revealed that the SH3 domain of c-Src kinase directly associates with the C-terminus of β3 integrin cytoplasmic tail. Here, we explore this binding interface with a combination of different spectroscopic and computational methods. Chemical shift mapping, PRE, transferred NOE and CD data were used to obtain a docked model of the complex. This model suggests a different binding mode from the one proposed through previous studies wherein, the C-terminal end of β3 spans the region in between the RT and n-Src loops of SH3 domain. Furthermore, we show that tyrosine phosphorylation of β3 prevents this interaction, supporting the notion of a constitutive interaction between β3 integrin and Src kinase.

Keywords: integrin, Src-kinase, NMR

Introduction

Integrins comprise a large family of bidirectional signaling receptors that tether extracellular matrix to the cytoskeleton and regulate cellular behavior via classical signaling pathways.1 These major cell surface receptors mediate cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death through “inside-out” and “outside-in” signaling events. Over the last decade, substantial progress has been made in structural characterization of integrins within these signaling cascades. Inside-out signaling is initiated by the separation of heterodimeric cytoplasmic tails causing an overall conformational change that propagates across the membrane to the extra-cellular domain of the receptor.2 In contrast, ligand binding to the extracellular domain leads to conformational changes across the receptor transducing the signal through the membrane, to the cytoplasm further leading to a series of downstream signaling events referred to as outside-in signaling.3 Major platelet integrin αIIbβ3, an archetypical representative of the class, regulates platelet aggregation and serves as a molecular scaffold interacting with various extracellular and intracellular binding partners. Shattil and co-workers4,5 have shown that outside-in signaling in platelets is mediated by a direct interaction of carboxyl terminus β3 integrin with Src kinase.

In humans, c-Src, a founding member of Src family non-receptor tyrosine kinases (SFKs), is a 60 kDa membrane anchoring cytosolic protein. The role of c-Src (hereafter referred to as Src) has been implicated in various cellular functions including cell division, motility, and cell survival. It is abundantly expressed in platelets and is vital to many vascular processes.6 Src is a multi-domain protein composed of: (i) an N-terminal myristoylation site, (ii) SH4 domain, (iii) SH3 domain, (iv) SH2 scaffold domain, and (v) catalytic kinase domain, followed by a tyrosine (Y527) containing C-terminal regulatory sequence. In resting cells, intra- and inter-molecular interactions mediated by Src SH2 domain and Csk (C-terminal Src kinase) respectively, maintain Src kinase in its auto-inhibited state, characterized by the phosphorylation of its Tyr527. This inactive form of Src is proposed to bind the resting β3 integrin cytoplasmic tail through its SH3 domain.7 Once integrins engage with their extracellular ligands, sequential αIIbβ3 microclustering induces the Src activation by a series of events including auto-phosphorylation of Tyr416 in the activation loop, dissociation of Csk and recruitment of phosphatase (PTP-1B) responsible for dephosphorylating Tyr527.7 Thus structural characterization of β3 integrin interaction with Src should help in the comprehension of its outside-in signaling events. This is particularly true for platelets, osteoclasts, and endothelial cells, where both proteins are found in abundance.4,7

Src SH3 domain, recognized as the key integrin binding site,5 has been extensively studied and structurally characterized in both free and ligand bound states (PDB: 1RLQ, 1QWF, 1NLP). It consists of two antiparallel β sheets positioned at right angles to one another. The β strands are linked via RT loop, n-Src loop, distal loop, and a short 310-helix.8,9 In general, SH3 domains are known to favor peptides bearing a PxxP motif.10 The PxxP motif adopts a polyproline type II (PPII) helix and binds between the RT loop and n-Src loop. The selectivity of these peptides is further enhanced by basic residues, arginines or lysines, which flank the core motif. In addition, other mechanisms may contribute towards the specificity of this interaction with the SH3 domain.11 Although two classes of peptides, class I—(R/K)xxPxxP and class II—PxxPx(R/K),10–12 are considered as canonical SH3 binding targets, accumulating evidence suggests that SH3 can also recognize non-PxxP motifs.10,13–15 The exact molecular details of such recognition still remain unclear. However, some non-PxxP peptides have been shown to occupy the same interface as PxxP motifs.16

In this article, we present the NMR data and a docked model of SH3 with cytoplasmic integrin β3. We also show that the C-terminal RGT motif of β3 adopts a partial PPII type helix facilitating its interaction with the RT and n-Src loops of SH3 in an orientation opposite to that obtained from X-ray studies.17 Finally, NMR titration studies demonstrate no interaction with the phosphorylated β3, supporting the idea of a constitutive interaction between non-stimulated/resting (non-phosphorylated) β3 integrin and the SH3 domain of Src kinase.

Results

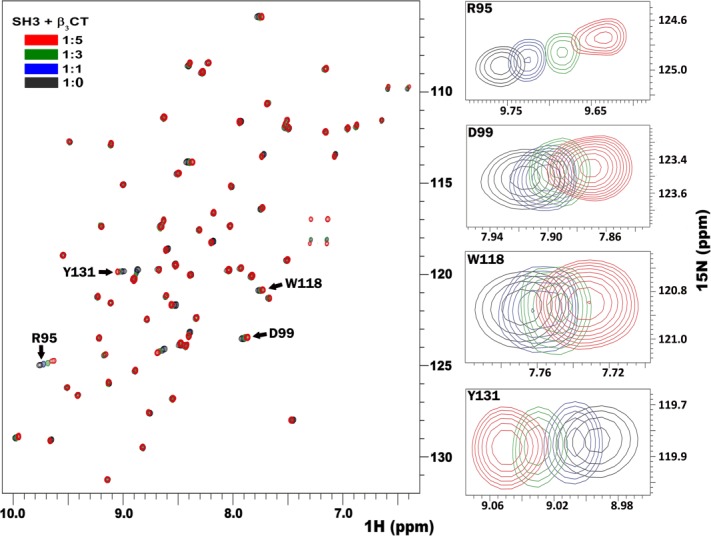

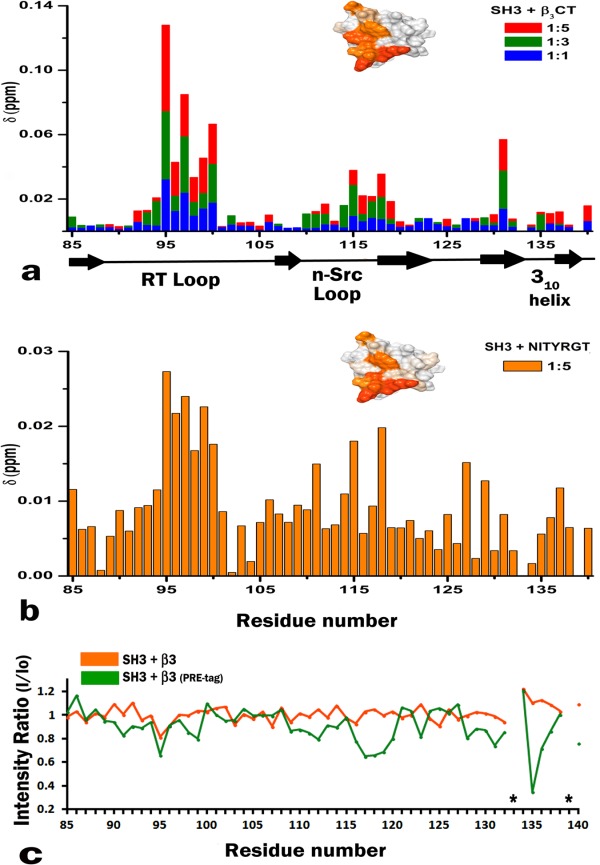

Previous studies have identified the C-terminal RGT762 motif of β3 integrin4,5,18 as the binding site for Src kinase through its SH3 domain. Hence we decided to map the binding site of this interaction onto the surface of SH3 using solution NMR. First, the full length unlabeled β3 cytoplasmic tail (hereafter referred to as β3CT) was titrated against 15N-labeled SH3. The 15N-HSQC spectra of SH3, shown in Figure 1, clearly indicate significant chemical shift differences when compared to the spectrum from free protein (shown in black). This titration was performed at an SH3 to β3 molar ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 1:5 while maintaining a constant pH throughout the experiment. The observed chemical shift differences, shown in Figure 2(a), were concentration dependent, reproducible, and specific to the interaction. Additionally, control experiments with the SH3 domain at different pH showed no similar effect, validating the perturbations being a consequence of binding. Amino acids affected the most, belong to the RT loop (residues R95 to L100) and the n-Src loop (E115 to W118), with Y131 perturbed in isolation. The RT loop amide peaks (R95, T96) were broadened upon titration, a manifestation of conformational exchange [Fig. 2(c) and also shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2]; while the peak intensities corresponding to the residues from the n-Src loop remained unaffected, suggesting a single conformation within this loop. Next, we tested β3 heptapeptide, composed of the last seven β3 residues containing the RGT motif. Chemical shift perturbation pattern obtained with β3 heptapeptide [Fig. 2(b)] closely resembled the one obtained with the full-length β3CT. The insets in Figure 2 represent the mapping of the chemical shifts onto the surface of SH3 domain (PDB: 1SRL) in the presence of full-length β3CT [Fig. 2(a)] and β3 heptapeptide [Fig. 2(b)]. The similar binding interfaces between the two confirms that the C-terminal motif of β3 is sufficient to define its binding to Src SH3 domain.

Figure 1.

The superimposition of 15N-HSQC spectra of Src SH3 (shown in black) in the presence of varying molar excess of β3CT as shown in blue (1:1), green (1:3) and red (1:5). Also shown to the right are several individual residues displaying significant shifts.

Figure 2.

(a) Chemical shift differences in SH3 HSQC spectra upon β3CT binding at different molar ratios. Bars are colored according to the different ratios as presented in Figure 1; Delta [ppm] refers to the combined HN and N chemical shift changes according to the equation: Δδ(HN,N) = [(ΔδHN2 + 0.2(ΔδN)2]1/2, where Δδ = δbound − δfree; The inset shows the chemical shift differences (obtained from 1:5 ratio) mapped onto the surface of SH3 domain (PDB: 1SRL), where the darker color represents the residues maximally affected. (b) Chemical shift differences obtained from the 15N HSQC spectrum of SH3 upon binding to β3 heptapeptide also at 1:5 ratio, further mapped onto the surface of SH3 domain (inset). (c) Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data of the backbone amide groups of SH3 in the presence of PRE tagged β3CT (green) in comparison to the untagged β3CT (orange). The asterisk mark represents proline residues.

We further used the chemical shifts mapping approach to test the influence of tyrosine phosphorylation, a characteristic feature of activated β3 receptor,19 on its binding to Src kinase. These titrations were performed against 15N-labeled SH3 with mono-(pY747) or bi-(pY747&pY759)-phosphorylated β3-derived peptides (MPCβ3 and BPβ3 respectively, refer to the Material and Methods section). Since no chemical shift differences were found in either case, even at a high molar ratio of 1 to 5 (Supporting Information Fig. S1), we concluded that tyrosine phosphorylation prevents SH3 from binding to β3. This finding is consistent with the previously suggested mechanism of constitutive interaction of Src with unactivated/resting, non-phosphorylated integrin β3.5

We additionally carried out Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) experiments to ascertain the orientation of bound integrin. A paramagnetic spin label was attached to the β3 mutant containing a cysteine residue added to its C-terminal end. The nitroxide radical from the spin label attenuates peak intensities of nearby residues allowing direct mapping of its location onto the binding surface. Since the label is attached next to the RGT motif, maximum attenuation is expected for SH3 residues adjacent to the ones involved in binding of this motif. To test whether the addition of a paramagnetic tag affected the interaction, we compared the spectra of SH3 in the presence of wild type β3CT and its tagged mutant (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Since no significant differences were observed we proceeded with the PRE analysis to study this interaction. 15N-HSQC spectra were collected at an SH3 to β3 mutant ratios of 1:2 and 1:4. Peak intensities for SH3 in complex with the tagged β3 mutant were normalized to the intensities of SH3 in complex with the untagged mutant. Maximum attenuation was observed for the residue N135 (with its side chain signals broadened beyond detection; Supporting Information Fig. S2) and a moderate decrease for Y136 suggesting their close proximity to the tag. A moderate decrease in the intensities of the n-Src loop also confirmed its positioning near-to the β3 RGT motif, while the RT loop was less affected, showing similar intensities to the bound untagged β3 [Fig. 2(c), shown in orange]. Attaching the tag to a cysteine residue present at the end of the C-terminus makes it quite flexible, hence preventing the quantitative analysis of the PRE data for structure calculations. However, having the N135 residue from the SH3 domain in close proximity to the nitric oxide from the tag, allowed us to reliably predict the orientation of the RGT motif within the SH3 binding interface.

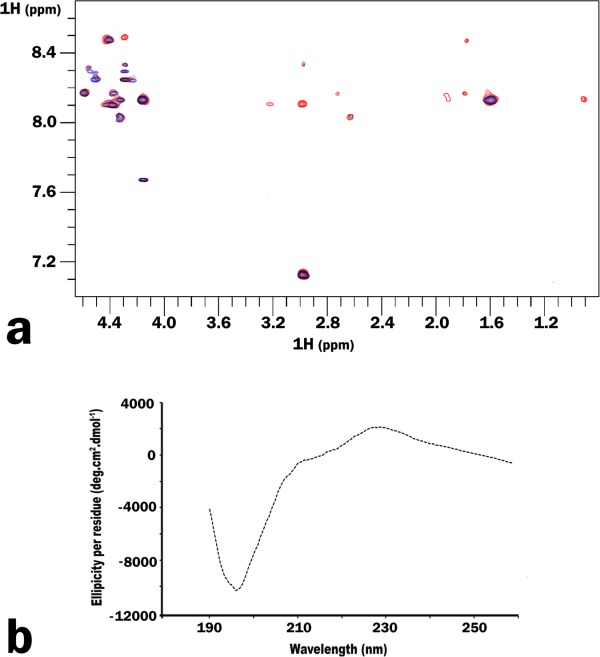

To further define the molecular details of the complex, in particular, the conformation of integrin C-terminus bound to the SH3 domain, we employed transferred NOE (trNOE). This method is best suited to study weakly associating systems comprising of small ligands bound to large molecules. NOESY spectrum of β3 heptapeptide, collected in the presence of GST-fused SH3 at an optimized peptide to protein molar ratio of 200 to 1, demonstrates the additional peaks manifesting the binding [Fig. 3(a)]. These peaks were absent in the control experiment with GST alone. Although partial assignments for the bound heptapeptide were made, insufficient amount of distance restraints deterred us from obtaining the complete structure of the complex. As no medium-range NOEs characteristic for α-helical secondary structure were observed, we speculate that upon binding the peptide exists as an ensemble of random coil and extended conformers. The secondary structure of the heptapeptide was further probed by circular dichroism (CD). The spectra showed a negative band at 197 nm and a positive band at 229 nm [Fig. 3(b)], reflecting the presence of a left handed PPII helix. Molar ellipticities per residue for these two bands are somewhat weaker for β3 heptapeptide when compared to the values reported in literature for peptides adopting a polyproline type II helix conformation.20,21 This suggests that β3 heptapeptide might adopt a partial PPII type helical conformation.

Figure 3.

(a) Superimposition of the NOESY spectra obtained for β3 hepta-peptide alone (blue) and in the presence of GST-SH3 (red). (b) Circular dichorism spectrum obtained for β3 hepta-peptide shows a negative band at 197 nm and a positive band at 229 nm, typical for a partial polyproline type II-like helix.

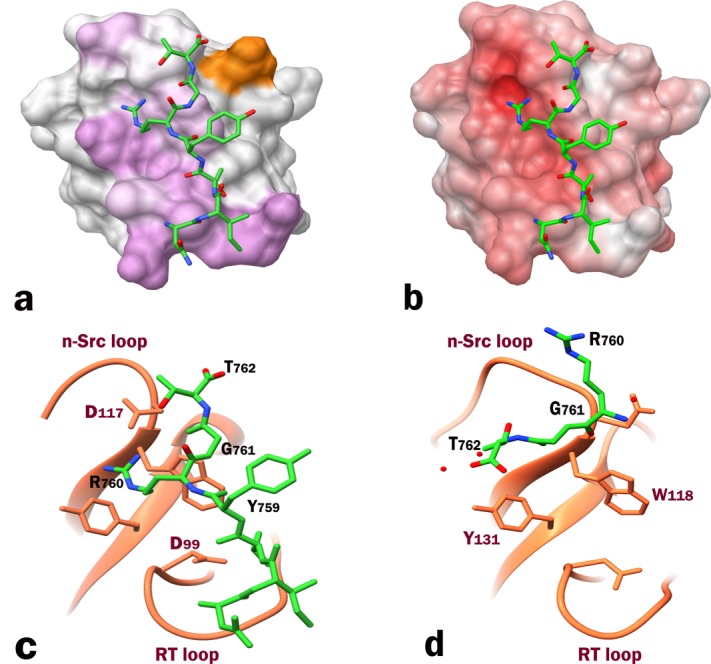

Various models of β3 heptapeptide were generated (with or without C-terminal paramagnetic label attached) using the Haddock (High Ambiguity data driven protein–protein DOCKing) web server22,23 to investigate the binding of β3 heptapeptide to SH3 domain (PDB: 1SRL). The ambiguous interaction restraints (AIRs) were defined by NMR titration and PRE experiments with the starting conformation of the heptapeptide consistent with our trNOE and CD data. Cluster analysis of the resulting 200 water-refined models reveals 72% (with the paramagnetic tag) and 69% (without tag) of these models belong to a single cluster. Both clusters accommodate very similar binding interfaces as shown in the inset of Supporting Information Figure S2. The backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) from the lowest energy model for the conformers from the cluster with tag is 1.1 Å, while for the conformers from the cluster without tag is 1.3 Å.

Discussion

The initial events in β3 integrin outside-in signaling rely on its association with the SH3 domain of Src kinase. We have deduced the molecular details of this interaction using NMR. Chemical shifts mapping experiments depict the C-terminus of β3 located between the RT and n-Src loops of SH3 domain, with Y131 from the β4 strand serving as a bridge between the two. As per our PRE results, the RGT motif binds to the pocket formed by the n-Src loop. The preceding NITY motif makes occasional intermediate contacts with the RT loop rendering its conformational heterogeneity.

The experimental data allowed us to obtain a reliable docked model of the complex using the HADDOCK web server. We are certain that our docking model provides a more accurate representation of the binding interface [Fig. 4(c)] than the recent X-ray model (PDB: 4HXJ) containing the RGT tri-peptide17 [Fig. 4(d)] for the following reasons: (i) We have used the longer construct, full length β3 cytoplasmic tail, in addition to the heptapeptide. According to our model, the RGT motif binds to n-Src loop while the remainder of the β3 tail extends into the RT loop. The “fishing hook” arrangement presented in the X-ray structure which places integrin on top of SH3, would not explain the conformational exchange in the RT loop observed in our titration experiments. Moreover, our CD data shows that the heptapeptide has a partial PPII helix, a characteristic feature of SH3 binding ligands which tend to interact between the RT and the n-Src loops. (ii) We have attached the paramagnetic tag to the C-terminal end of RGT sequence, which allowed us to orient the RGT motif unambiguously with respect to its SH3 binding pocket. If the orientation were to be as per the X-ray structure, we would have seen the PRE effect opposite to the current site on SH3's surface. Moreover, the weak electron density map, used to fit the small RGT tri-peptide, could easily lead to an ambiguous orientation. This ambiguity is further accentuated by the following two observations form the X-ray structure: the average B-factor for RGT is 67 Å2, much higher than that of the SH3 domain itself (13.5 Å2), and the asymmetric unit of the crystal structure containing two SH3 molecules binds to a single RGT peptide. (iii) Our model also supports the biochemical studies that have clearly shown the importance of R760 from integrin β3 YRGT motif and D117, W118, and Y131 residues from the SH3 domain.17 According to our model, the partial PPII characteristic of the peptide allows arginine side chain from the RGT motif to be positioned between the aromatic residues W118 and Y131 within the specificity pocket. This allows R760 to easily interact with either of the residues, while no such interactions occur in the X-ray model. Additionally, the guanidinium group of R760 forms a salt bridge with the side chains of either D99 or D117 or with both, as shown by some conformers of the ensemble, while in the X-ray model this crucial arginine exhibits predominantly hydrophobic contacts with a single backbone amide hydrogen bonded to D117. (iv) Furthermore, the electrostatic surface potential of SH3, presented for the apo-domain in Supporting Information Figure S3(a) and for our model in Supporting Information Figure S3(c) provides a more plausible binding opportunity that is driven by polar interactions between the negatively charged groove on the SH3 surface and positively charged side-chain of R760, proving critical for the complex formation17 and shown to enhance selectivity (as an R/Kxx or xR/K addition) when linked to PxxP, the canonical SH3 binding motif.11 The surface potential for SH3 domain calculated based upon the coordinates from the X-ray complex (PDB: 4HXJ), presented in Supporting Information Figure S3(b), makes it electrostatically unfavorable to place the negatively charged carboxyl end of the peptide into the negatively charged groove on SH3.

Figure 4.

(a) β3 heptapeptide docked onto Src SH3 domain using HADDOCK program. Chemical shift perturbations are mapped in purple. Additionally, the residue most affected by the spin label is shown in orange. (b) Electrostatic surface potential of SH3 domain bound to β3 heptapeptide (colored with +6 kT/e). (c) A ribbon representation of the binding interface obtained from the docked model highlighting R760 which could make potential contacts with either D99 or D117 in the specificity zone. (d) X-ray structure of the RGT peptide in complex with SH3 domain (PDB: 4HXJ) comparatively showing the reverse orientation of the peptide.

The X-ray structure of the inactive Src kinase (PDB: 2SRC) shows the linker connecting the SH2 and the kinase domains in close proximity to the RT and n-Src loops of SH3 domain.24 The question remains whether β3 binds to Src kinase in its inactive closed form in the presence of the linker, and, if so, how does the linker affects its affinity for Src kinase. Or, alternatively, β3 might bind to the open form, replacing the linker, thus preventing Src kinase from becoming inactive and maintaining a small population of active kinase partially poised to start the activation process induced by integrin microclustering.

In light of the proposed mechanism of outside-in signaling,7 where some integrin β3 molecules are primed for activation of Src kinase, the weak binding as observed from our trNOE experiments seem pertinent. In addition, we have further investigated whether SH3 domain binds to the phosphorylated β3 and found no interaction, suggesting that Src can be associated with integrin through its SH3 domain only in the resting non-phosphorylated state of the receptor. We believe that this weak but constitutive interaction would keep Src tethered to the integrin and consequently bring two or more Src kinases to close proximity upon integrin activation via clustering.5 This, in turn, would aid in trans-activation of the kinase through auto-phosphorylation of Y418 in the Src activation loop.

In conclusion, our chemical shifts mapping data in concert with PRE, trNOE and CD studies have confirmed the RGT762 motif of β3 integrin as the binding site for Src kinase. We have used these datas to generate a reliable model of the complex through docking. Furthermore, we have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of β3 cytoplasmic tail prevents it from binding to SH3, corroborating the reports of a constitutive interaction between resting integrin β3 and Src kinase.5

Materials and Methods

Peptides

β3 heptapeptide (NITYRGT762), mono (ATSTFTNITpYRGT762), and bi-phosphorylated (RAKWDTANNPLpYKEATSTFTNITpYRGT762) C-termini of β3 (MPCβ3 and BPβ3 respectively) were synthesized chemically (Genemed Synthesis; NEO-peptides).

Expression and purification

Cloning, expression, and purification of cytosolic β3 was done as described elsewhere.2 The human Src SH3 (residue 80–144) in pGEX-4T1 vector was expressed in BL21(DE3) after induction with 1 mM IPTG. To produce 15N isotopically labeled Src SH3, cells were grown in M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl. GST-tagged SH3 was purified in PBS buffer (140 mM NaCl, 27 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2) using Pierce Glutathione Agarose resin (Thermo Scientific). SH3 was eluted by either cleavage with thrombin or by using 10 mM glutathione in PBS buffer. The eluate was further purified through HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with PBS buffer.

NMR spectroscopy

All experiments were performed at 25°C using 0.1 mM protein samples (unless otherwise mentioned), on 600 MHz magnet (Agilent) equipped with inverse-triple resonance cold probe. 15N-HSQC titration: Concentrated stock solutions of β3 peptides were prepared in the same buffer as Src and added to the 15N-labeled SH3 domain at different peptide to protein molar ratios. Each data point was also reverse titrated beginning from the saturated conditions for the peptides. Experiments were performed at pH 5.8. The SH3 spectra at different pH were collected as a negative control. All the spectra were collected with 2048 complex data points in t2 and 128 increments in t1 dimensions and zero filled to 2048 × 1024 data points. The spectra were processed with NMRPipe25 and analyzed by CCPN software suite.26 Chemical shift assignments for SH3 domain were obtained from BMRB database entry 3433.9 The shifts were adjusted to match our experimental conditions. Transferred NOE: β3 heptapeptide was mixed with GST-fused SH3 at pH 6.5. Different peptide to SH3 ratios were investigated to find the optimal one for NOE transfer in two-dimensional proton NOESY experiments with the mixing time of 400 ms. A negative control with just the GST tag was performed under the same conditions at an optimized heptapeptide to GST ratio of 200 to 1. Partial 1H resonance assignments for the heptapeptide were obtained by collecting TOCSY (mixing time of 70 ms) and NOESY (mixing time of 400 ms) spectra. Paramagnetic Labeling: In order to introduce a spin label, β3 mutant was constructed with an additional cysteine residue after the terminal YRGT sequence using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). Prior to the reaction, the mutant was reduced by 1 mM TCEP, which was subsequently removed by washing on a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). The reduced β3 mutant was allowed to react overnight with either an excess of cysteine specific spin label, 3-maleimido-PROXYL, hereafter referred to as mProxyl (Sigma-Aldrich), or 1-Oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate, hereafter referred to as MTSL (Alexis Biochemicals). The reactions were performed at room temperature at a pH of 7.0. The unreacted spin label was separated from the tagged mutant by reverse phase HPLC on PROTO C4 column (The Nest Group). Attachment of the tag was confirmed through mass spectrometry. 15N-HSQC spectrum of SH3 in the presence of tagged β3 mutant (as well as a control with untagged mutant) was collected under the same conditions as used for wild type β3 titrations.

Circular dichroism

CD experiments were done on PiStar 180 Spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, UK). The sample was prepared by dissolving β3 heptapeptide in 20 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6.5. Spectrum was collected in the far UV range at 25°C with a step resolution of 0.5 nm, bandwidth of 3.0 nm and data averaging of 30 s/point.

Electrostatic potentials mapping

The potential files used for mapping were prepared from the respective PDB files by Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver (APBS),27 a program that maps the electrostatic potential energy based on Poisson–Boltzmann equation. The resultant (.pqr and.in) files from pdb2pqr webserver served as input for APBS calculations. APBS webserver as well as Chimera's APBS built-in tool were used to prepare the electrostatic potential maps which further rendered the electrostatic surface using Chimera's Electrostatic Surface Coloring tool. Alternatively the surface potential was also directly mapped using Coulombic surface mapping.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jun Qin for the Src-SH3 plasmid. We are grateful to Dr. Amy Anderson and Stephanie Reeve for their help in retrieving and analyzing the raw X-ray data of SH3:RGT complex, Margaret Suhanovsky for assistance with CD experiments and Dr. Vitaliy Gorbatyuk for help with docking.

Glossary

- BPβ3

bi-phosphorylated integrin β3 peptide

- MPCβ3

C-terminus mono-phosphorylated β3 peptide

- CT

cytoplasmic tail

- PRE

paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- trNOE

transferred nuclear overhauser effect

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinogradova O, Velyvis A, Velyviene A, Hu B, Haas T, Plow E, Qin J. A structural mechanism of integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) "inside-out" activation as regulated by its cytoplasmic face. Cell. 2002;110:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Calderwood DA, Ginsberg MH. Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3563–3571. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Specification of the direction of adhesive signaling by the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29699–29707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias-Salgado EG Lizano S, Sarkar S, Brugge JS, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13298–13302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roskoski R., Jr Src kinase regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shattil SJ. Integrins and Src: dynamic duo of adhesion signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordier F, Wang C, Grzesiek S, Nicholson LK. Ligand-induced strain in hydrogen bonds of the c-Src SH3 domain detected by NMR. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:497–505. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Rosen MK, Schreiber SL. 1H and 15N assignments and secondary structure of the Src SH3 domain. FEBS Lett. 1993;324:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81538-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer BJ. SH3 domains: complexity in moderation. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1253–1263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarrinpar A, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. The structure and function of proline recognition domains. Science's STKE. 2003:RE8. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.179.re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng S, Chen JK, Yu H, Simon JA, Schreiber SL. Two binding orientations for peptides to the Src SH3 domain: development of a general model for SH3-ligand interactions. Science. 1994;266:1241–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.7526465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang H, Freund C, Duke-Cohan JS, Musacchio A, Wagner G, Rudd CE. SH3 domain recognition of a proline-independent tyrosine-based RKxxYxxY motif in immune cell adaptor SKAP55. EMBO J. 2000;19:2889–2899. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishan KV, Scita G, Wong WT, Di Fiore PP, Newcomer ME. The SH3 domain of Eps8 exists as a novel intertwined dimer. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:739–743. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mongiovi AM, Romano PR, Panni S, Mendoza M, Wong WT, Musacchio A, Cesareni G, Di Fiore PP. A novel peptide-SH3 interaction. EMBO J. 1999;18:5300–5309. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kami K, Takeya R, Sumimoto H, Kohda D. Diverse recognition of non-PxxP peptide ligands by the SH3 domains from p67(phox), Grb2 and Pex13p. EMBO J. 2002;21:4268–4276. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao R, Xi XD, Chen Z, Chen SJ, Meng G. Structural framework of c-Src activation by integrin beta3. Blood. 2013;121:700–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-440644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ablooglu AJ, Kang J, Petrich BG, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Antithrombotic effects of targeting alphaIIbbeta3 signaling in platelets. Blood. 2009;113:3585–3592. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips DR, Prasad KS, Manganello J, Bao M, Nannizzi-Alaimo L. Integrin tyrosine phosphorylation in platelet signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:546–554. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly MA, Chellgren BW, Rucker AL, Troutman JM, Fried MG, Miller AF, Creamer TP. Host-guest study of left-handed polyproline II helix formation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14376–14383. doi: 10.1021/bi011043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rucker AL, Creamer TP. Polyproline II helical structure in protein unfolded states: lysine peptides revisited. Protein Sci. 2002;11:980–985. doi: 10.1110/ps.4550102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries SJ, van Dijk M, Bonvin AM. The HADDOCK web server for data-driven biomolecular docking. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:883–897. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M, Eck MJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon MJ. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.