Abstract

Liquid chromatography in tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as an informative tool to investigate oxysterols (oxidized derivatives of cholesterol) in helminth parasite associated cancers. Here, we used LC-MS/MS to investigate in soluble extracts of the adult developmental stage of O. viverrini from experimentally infected hamsters. Using comparisons with known bile acids and the metabolites of estrogens, the LC-MS data indicated the existence of novel oxysterol derivatives in O. viverrini. Most of these derivatives were ramified at C-17, in similar fashion to bile acids and their conjugated salts. Several were compatible with the presence of an estrogen core, and/or hydroxylation of the steroid aromatic ring A, hydroxylation of both C-2 and C-3 of the steroid ring and further oxidation into an estradiol-2,3-quinone.

Keywords: bile acids, flukes, Opisthorchis viverrini, oxysterols

1. Introduction

Liver fluke infection caused by Opisthorchis viverrini, Clonorchis sinensis and related flukes remains a major public health problem in East Asia and Eastern Europe where >40 million people are infected. O. viverrini is endemic in Thailand, Lao PDR, Vietnam and Cambodia. Humans acquire the infection by eating raw or undercooked fish infected with the metacercaria (MC) stage of the parasite (reviewed in [1]). Upon ingestion, MCs excyst in the duodenum and juvenile flukes migrate into the biliary tree. In the bile ducts, the parasites mature over six weeks into adult flukes which graze on biliary epithelia. Parasites eggs are shed in the fecal stream and the eggs are ingested by freshwater snails. The parasite undergoes transformations within the snail host, culminating in the release of cercariae which seek out and penetrate the skin of a freshwater fish. The infection in humans causes hepatobiliary abnormalities, including cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly, periductal fibrosis, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis [1]. Much more problematically, both experimental and epidemiological evidence strongly implicates liver fluke infection in the etiology of one of the major liver cancer subtypes cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), bile duct cancer [2].

Opisthorchiasis is associated with elevation of bile acids, including deoxycholic acid (3, Supplementary Table 1), which are potent tumor promoters in cholangiocarcinogenesis. Bile acids (Supplementary Table 1) are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol, and the majorities are conjugated with either glycine or taurine [3–7]. Inflammation-related carcinogenesis has also been associated to oxidative and nitrative DNA damage as 8-oxo-7,8-hydro-2′-deoxiguanine (8-oxodG) and 8-nitroguanine (8-NG) [4]. Akaike et al [5] demonstrated the close association of 8-nitroguanosine with NO production in mice with viral pneumonia. Increased levels of nitrate and nitrite, which reflect endogenous generation of NO, have also been detected during O. viverrini infection in humans [6] and animals [7]. In view of the above, a study on nucleic acid damage by reactive nitrogen and oxygen species may contribute to clarification of mechanisms of carcinogenesis triggered by O. viverrini infection.

Oxysterols, which are oxidation products of cholesterol not generated by enzymatic or enzymatic (P450) reactions, have been shown to be mutagenic, genotoxic, and to possess pro-oxidative and pro-inflammation properties that can contribute to carcinogenesis. Binding domains in human genes studies have demonstrated an association between different types of oxysterols and the development and progression of cancer of the colon, lung, breast and bile ducts. Given our experience in LC-MS/MS studies towards drug development [16–21] or understanding of the molecular basis of disease [8,9], we set out to explore the prospective presence of novel steroids in O. viverrini, in line with recent findings on steroid metabolites reported by others and us [8,10].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Extracts of Opisthorchis viverrini liver flukes

Metacercariae of O. viverrini were obtained from naturally infected cyprinoid fish in Khon Kaen province, Thailand. The fish were digested by the pepsin-HCl method. After several washes with normal saline, metacercariae were collected and identified under a dissecting microscope. Metacercariae were used to infect hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), which were maintained at the rodent facility of the Faculty of Medicine at Khon Kaen University. Protocols approved by the Khon Kaen University Animal Ethics Committee were used for this investigation (Animal Ethic No. AEKKU 05/2550). At about three months after infection, hamsters were euthanized and necropsied, and adult O. viverrini flukes recovered from their bile ducts. The worms were washed extensively in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing antibiotics (100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin G) and cultured overnight in serum free RPMI-1640 medium containing 1% glucose, and protease inhibitors (0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 2μM E-64 and 10μM leupeptin) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 [11]. Then, the worms were washed thoroughly with PBS. Soluble extracts of these worms were prepared by sonication (5×5 s bursts, output cycle 4, Misonix Sonicator 3000, Newtown, CT 06470, USA) in PBS supplemented with protease inhibitors (500 μM AEBSF, HCl, 150 nM aprotinin, 1 μM E-64, and 1 μM leupeptin hemisulfate) (EMD Millipore, Calbiochem, Billerica, MA, USA), followed by 30-min centrifugation at 10000 rpm and 4°C. Supernatants were collected and protein concentration determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA kit, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). These soluble extracts of O. viverrini worms were stored in small aliquots at −80°C until needed.

Methanol was added to the soluble extract of O. viverrini worms (with lipidic fraction) to 20% (volume/volume); 25 μl of this solution was injected into the LC-MS/MS instrument for analysis. Methanol displayed excellent chromatographic performance (separation and sensitivity) with short gradient times possible for chromatographic separation with this solvent.

2.2. LC-MS/MS analysis

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was employed to investigate relevant molecular species in the soluble extracts from adult O. viverrini worms. The HPLC module was constituted with a thermostatted automated sample injector and a thermostatted column compartment; the column was a 125×4.6 cm Merck Purospher STAR RP-18e (3 μm), equipped with a Merck Lichrocart pre-column (Merck, Germany) and the mobile phase consisted of 1% acetic acid in water (A) / acetonitrile (B) mixtures; elution was carried out at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, with the following programme: 0–5 min, 100% A; 5–10 min, linear gradient from 100% to 80% A; 10–15 min, 80% A; 15–50 min, linear gradient from 80 to 40 % A; 50–65 min, 40% A; 65–75 min, linear gradient from 40% A to 100% B; detection was achieved on a diode array detector (DAD) at 280 nm. MS analysis relied on a Finnigan Surveyor LCQ XP MAX quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA) utilizing electrospray ionization. Mass spectra were acquired in the negative mode (species mainly detected as [M-H]− ions or M−).

3. Results

The introduction and refinement of LC-MS/MS methods have made the analysis of conjugated bile acids possible with high sensitivity, minimal sample size requirements and simplified sample preparation procedures [28]. In view of this, we developed an LC-MS/MS approach to search for new steroid-based molecules whose presence in extracts of O. viverrini worms we had postulated on the basis of bile acids and the metabolism of estrogens [8,10]. Figure 1 depicts the full chromatogram (MS detection) obtained for the worm extracts, and relevant data from MS analysis are presented in Table 1, along with the structures postulated to be associated with each of the main species detected here.

Figure 1.

Full chromatogram (MS detection) obtained in the LC- MS/MS analysis of soluble extracts of adult O. viverrini worms; the X-axis presents the retention time (r. t.) on the LC column, the Y-axis shows the relative abundance of each component.

Table 1.

Postulated structures for components detected by LC-MS/MS analysis of extracts of adult O. viverrini worms; # represents the number of structure in this report, MS is the principal peak observed in mass spectrum, MS2 is the first fragmentation of principal peak observed in MS, and r.t. is the retention time.

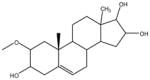

| Compound # | Postulated structure | m/z | r.t. (min.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | MS2 | |||

| 9 |

|

384.87 | - | 16.49 |

| 10 |

|

716.07 | 656.02 511.98 453.17 |

17.99 |

| 11 |

|

802.40 | 742.20 724.13 597.87 |

18.53 |

| 12 |

|

355.87 | - | 19.45 |

| 13 |

|

577.13 | - | 20.85 |

| 14 |

|

335.07 | - | 21.60 |

| 15 |

|

357.13 | - | 30.45 |

| 16 |

|

438.93 | - | 38.84 |

| 17 |

|

667.20 | 515.07 497.00 541.27 |

39.20 |

| 18 |

|

455.13 | - | 41.90 |

| 19 |

|

329.47 | - | 43.12 |

| 20 |

|

495.13 | 407.20 450.72 340.80 |

45.20 |

| 21 |

|

280.87 | - | 48.47 |

| 22 |

|

757.23 | 649.13 540.93 497.07 |

49.11 |

| 23 |

|

255.20 | - | 50.10 |

| 24 |

|

529.07 | 393.60 | 51.98 |

| 25 |

|

887.07 | 882.57 859.95 803.94 |

57.78 |

| 26 |

|

451.20 | - | 59.34 |

As shown on Table 2, most of the proposed structures present C-17 ramification (i.e. discrete and variable chains linked to carbon 17 of the steroid ring), in similar fashion to bile acids and their conjugated salts. Also, MS data are compatible with the presence of derivatives of catechol-estrogens and other components hydroxylated at the steroid ring, including at both C-2 and C-3 and respective oxidized 2,3-quinone.

Some oxidative metabolites of estrogens can react with DNA and the mutations resulting from these adducts can lead to cell transformation. Bile acids constitute a large family of steroids carrying a carboxyl group in the side chain, e.g. 10, 11, 11 and 22. Bile alcohols have similar products in bile acid biosynthesis or as end products, and we can see these compounds in 18, 19 and 26, but conjugated at different positions. Free bile acids are reconjugated in some species like aldehydes (12 and 15) or as sulfates (20, 24 and 25). The effects of these individual species can be anticipated to be structure-dependent, and metabolic conversions will result in a complex mixture of biologically active and inactive forms.

4. Discussion

Chronic infection by the liver fluke O. viverrini is associated with carcinogenesis of CCA. ROS/RNS generated during inflammatory response to O. viverrini possess highly oxidative potential [12]. These oxidative species could react with biomolecules in inflammatory area which include of O. viverrini residing in bile duct. Cholesterol is one of the targets of the free radicals. Here, we identified oxidized derivatives, oxysterols, from the liver fluke O. viverrini, which might - at least in part – be generated from non-enzymatic reaction by the oxidative free radicals. It is also feasible that these novel oxysterols are produced enzymatically by the liver fluke, and in this regard, the prospective occurrence of cholesterol metabolic enzymes in fluke tissues deserves to be investigated. On the other hand, O. viverrini worms reside within the biliary tree, bathed in bile, and hence some of these oxysterol like species may be of host origin. Regardless of the provenance of these metabolites, the parasite might take up and/or utilize these oxysterols for its own needs or benefit.

Since oxysterols can traverse cell membranes more quickly than cholesterol, oxysterols of O. viverrini origin might enter biliary epithelia and contribute to O. viverrini-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Moreover, oxysterols may contribute at several stages of carcinogenesis; 1) tumor initiation by enhancing the production of ROS/RNS and 2) tumor promotion through upregulated expression COX-2 leading to the alteration of cellular phenotypes [14]. Also, oxysterols may support cancer progression through the induction of migration and/or may exert their effect by binding to specific proteins and activating signaling cascades. Oxysterols have been identified in livers of hamsters infected with O. viverrini that develop cholangiocarcinoma; among others, both Triol and 3K4 occur at elevated levels in the livers of hamsters with O. viverrini-induced cholangiocarcinoma. In concert with the novel liver fluke oxysterols reported here migh contribute to cholangiocarcinoma including through formation of DNA adducts and dysregulation of apoptosis and other homeostatic pathways [14–16].

Most of the bile acids excreted to bile duct are reabsorbed in the intestine and return to liver via portal vein. Reabsorbed bile acids act as a negative regulator of the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol catabolism termed cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) in the liver, which in turn slow down bile acid production [13]. The oxysterols in O. viverrini adult worms released into bile duct, some of them are structurally similar to bile acid, might act the same way as bile acid to down regulate the bile acid metabolism. In turn, this might contribute to digestive dysfunction that is not uncommon during opisthorchiasis [17], and hence further investigation of this issue can be expected to be informative. Nonetheless, whereas we anticipate that similar physiological phenomena take place in infected humans, the present study investigated worms from experimentally infected hamsters.

A water soluble lysate of O. viverrini liver flukes was investigated here because we wanted to investigate soluble forms of oxysterol(s). This would likely reflect physiological forms released/exported/secreted from the liver fluke in vivo. Since we wondered whether oxysterols might be involved in carcinogenesis of liver fluke induced bile duct cancer, it seems likely that soluble forms would be transferred from the worm to surrounding tissues. One possible mechanism for transferring of these oxysterols is binding to carrier proteins, including fatty acid binding proteins in tegumental membrane and excretory-secretory products of O. viverrini ( Mulvenna J, Sripa B, Brindley PJ, et al 2010 The secreted and surface proteomes of the adult stage of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini. Proteomics 10, 1063–1078). Fatty acid binding proteins are members of lipid-binding protein family that serve as carrier proteins for hydrophobic ligand trafficking (Smathers RL, Petersen DR.2011 “The human fatty acid-binding protein family: evolutionary divergences and functions”. Hum Genomics 5 (1): 170–191). The mechanism and role of these proteins in O. viverrini also are being investigated in our laboratories.

MS analysis alone cannot provide a conclusive structural assignment. Nonetheless, we have used caution in interpreting the new LC-MS data in light of what has been reported/ is known about metabolism of bile acids and estradiol [8,18–20]. Furthermore, our structural interpretation of MS data for the postulated novel oxysterols is further supported by MS fragmentation analysis, presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

MS/MS analysis of several putative oxysterols (numbering according to Table 1) detected in soluble extracts of adult O. viverrini worms, including structures hypothesized for fragments.

We have postulated structures based only on the mass of the [M-H]− ion associated to each component detected by the LC-MS/MS analysis of O. viverrini extracts. However, in view of all the above, and based on the literature available about bile acids and the metabolism of estrogen-related biomolecules [18,19], the structures presented in Table 2 are likely to be valid. Some of these structures represent the estrogen core with minimal or only a few changes, e.g. 9, 12–15, 23 and 24. The majority of these exhibit C-17 ramifications, similar to structures of bile acids and their conjugated salts e.g. 10, 11, 17–20, 22, 25 and 26 (Table 2). In addition, structure 18 is compatible with a pattern of steroid-ring hydroxylation on both C-2 and C-3 and further oxidation into an estradiol-2,3-quinone. Overall, the proposed structures suggest that carcinogenesis-related steroids may be present in significant amounts in the adult O. viverrini liver fluke. It also should be noted that a relation between putative oxysterol or bile acid metabolites from O. viverrini and bile duct cancer has been previously hypothesized, in pioneering studies by Thai investigators during 1980s [21].

The chemical structures of oxysterols vary depending upon the number and position of oxygenated functional group, and include keto-, hydroxyperoxy, and epoxy forms. Enzymatic pathways that result in production of oxysterols mainly involve cytochrome P450 family enzymes, but certain oxysterols are produced by non-enzymatic oxidation (or auto-oxidation), a process that involves reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [22]. Oxysterols can act as intermediates in cholesterol catabolism, especially in synthesis of bile acids [23,24]. Bile acids, in turn, are acidic molecules with pKa values of ~1.5 for taurine-conjugated, ~4.5 for glycine-conjugated, and ~6.0 for unconjugated bile acids [25]. Thus, detection of bile acids and respective conjugates in ionized/non-ionized forms will depend on the pH of the mobile phase [26,27]. In our case, where a slightly acidic mobile phase was employed, taurine conjugates would be mainly deprotonated, and glycine and unconjugated bile acids would occur predominantly in the non-ionized form.

Cytochrome P450 enzymes play a critical role in both estrogen formation and its subsequent oxidative metabolism. The biosynthesis of estrogen hormones from androgens is mediated by the action of aromatase, a cytochrome P450 specific enzyme. Subsequent to their synthesis, estrogens undergo extensive metabolism [10]. The oxygenated metabolites of estrogens represent structures with newly generated hydroxyl and keto functions at specific sites in the steroid nucleus, which are analogous to other steroid categories that undergo oxidative metabolism, as androgens, vitamin D and bile acids [28]. The estrogens also share with other steroids similar modes of conjugative metabolism involving the formation of sulfates and glucoronides. Recently, we reported novel estrogenic conjugates with guanine [8], and although steroid and/or bile acid metabolites apparently have not been reported before for O. viverrini, formation of 8-oxodG and 8-NG have been described in the course of O. viverrini infection [4].

To conclude, advances in the methods of LC-MS/MS have facilitated the analysis of conjugated bile acids with high sensitivity, requiring only minimal quantities of the samples, and simplified sample preparation procedures [18]. As such, LC-MS/MS was utilized in this study, which enabled us to putatively identify novel oxysterols in adult O. viverrini liver flukes. Whereas the role of these new oxysterols of O. viverrini in bile duct cancer remains to be examined, this topic clearly is worthy of deeper investigation. Future studies will aim at isolation or chemically synthesis of some of these oxysterols and downstream investigation of interactions of the fluke oxysterols with informative cells such as cholangiocytes [15] and with oxysterol binding proteins (OSP). Given that other metabolites of O. viverrini also are predicted to play a role in tumorigenesis of O. viverrini induced bile duct cancer, including liver fluke granulin [29], it will be informative also to compare and contrast action of liver fluke granulin and the fluke oxysterols in these analyses. OSP are potential biomarkers of liver fluke induced liver cancer [16]. As ligands of OSP, O. viverrini-derived oxysterols and related metabolites may become useful biomarkers for O. viverrini infection and associated diseases [30].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

LC-MS/MS and novel oxysterols in O. viverrini worms

Oxysterols are ramified in C-17 and compatible with the presence of an estrogen core

Conjugation of these steroid derivatives with guanine may lead to DNA damage of bile duct epithelia

Acknowledgments

PG and NV thank Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT, Portugal) and FEDER (European Union) for funding through project grants CONC-REEQ/275/QUI and PEst-C/QUI/UI0081/2011. NV also thanks FCT for Post-Doc grant SFRH/BPD/48345/2008. JMCC thanks also FCT for Pest-OE/AGR/UI0211/2011 and Strategic Project UI211–2011–2013. PJB received support from award R01CA155297 and R01CA164719 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sithithaworn P, Andrews RH, Van De N, Wongsaroj T, Sinuon M, Odermatt P, Nawa Y, Liang S, Brindley PJ, Sripa B. The current status of opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis in the Mekong Basin. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sripa B, Pairojkul C. Cholangiocarcinoma: lessons from Thailand. Curr Opin Gastroen. 2008;24:349–356. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282fbf9b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirica AE. Cholangiocarcinoma: Molecular targeting strategies for chemoprevention and therapy. Hepatology. 2005;41:5–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yongvanit P, Pinlaor S, Bartsch H. Oxidative and nitrative DNA damage: Keys event in opisthorchiasis-induced carcinogenesis. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akaike T, Okamoto S, Sawa T, Yoshitake J, Tamura F, Ichimori K, Miyazaki K, Sasamoto K, Maeda S. 8-nitroguanosine formation in viral pneumonia and its implication for pathogenesis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:685–690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235623100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haswell-Elkins MR, Satarug S, Tsuda M, Mairing E, Esumi H, Sithithaworn P, Mairiang P, Saitoh M, Yongvanit P, Elkins DB. Liver fluke infection and cholangiocarcinoma: model of endogenous nitric oxide and extragastric nitrosation in human carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1994;305:241–252. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohshima H, Bandaletova TY, Brouet I, Bartsch H, Kirby K, Ogunbiyi F, Vatanasapt V, Pipitgool V. Incresead nitrosamine and nitrate biosynthesis mediated by nitric oxide synthase induced in hamster infected with liver fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini) Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:271–275. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botelho MC, Soares R, Vale N, Ribeiro R, Camilo V, Almeida R, Medeiros R, Gomes P, Machado JC, Costa JMC. Schistosoma haematobium: Identification of new estrogenic molecules with estradiol antagonistic activity and ability to inactive estrogen receptor in mammalian cells. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vale N, Fernandes I, Moreira R, Mateus N, Gomes P. Comparative analysis of in vitro rat liver metabolism of the antimalarial primaquine and a derived imidazoquine. Drug Metabol Lett. 2012;11:15–25. doi: 10.2174/187231212800229273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martucci CP, Fishman C. P450 enzymes of estrogen metabolism. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;57:237–257. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90057-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suttiprapa S, Loukas A, Laha T, Pongkham S, Kaewkes S, Gaze S, Brindley PJ, Sripa B. Characterization of the antioxidant enzyme, thioredoxin peroxidase, from the carcinogenic liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;120:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawanishi S, Hiraku Y, Pinlaor S, Ma N. Oxidative and nitrative DNA damage in animals and patients with inflammatory disease in relation to inflammation-related carcinogenesis. Biol Chem. 2006;387:365–372. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björkhem I. Do oxysterols control cholesterol homeostasis? J Clin Invest. 2002;110:725–730. doi: 10.1172/JCI16388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jusakul A, Loilome W, Namwat N, Haigh WG, Kuver R, Dechakhamphu S, Sukontawarin P, Pinlaor S, Lee SP, Yongvanit P. Liver fluke-induced hepatic oxysterols stimulate DNA damage and apoptosis in cultured human cholangiocytes. Mutat Res. 2012;731 (1–2):48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jusakul A, Loilome W, Namwat N, Haigh WG, Kuver R, Dechakhamphu S, Sukontawarin P, Pinlaor S, Lee SP. Liver fluke-induced hepatic oxysterols stimulate DNA damage and apoptosis in cultured human cholangiocytes. Mutat Res. 2012;731:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loilome W, Wechagama P, Namwat N, Jusakul A, Sripa B, Miwa M, Kuver R, Yongvanit P. Expression of oxysterol binding protein isoforms in opisthorchiais-associated cholangiocarcinoma: A potential molecular marker for tumor metastasis. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mairiang E, Mairiang P. Clinical manifestation of opisthorchiasis and treatment. Acta Trop. 2003;88:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gouveia MJ, Botelho M, Brindley PJ, Costa JMCC, Gomes P, Vale N. Mass spectrometry techniques in the survey of steroid metabolites as potential disease biomarkers: a review. Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.003. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Unbalanced metabolism of endogenous estrogens in the etiology and prevention of human cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;125:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lövgren-Sandlom A, Heverin M, Larsson H, Lundström E, Wahren J, Diczfalusy U, Björkhem I. Novel LC-MS/MS method of assay of 7a-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one in human plasma. Evidence for a significant extrahepatic metabolism. J Chromatogr A. 2007;856:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Migasena S, Egoramaiphol S, Tungtrongchitr R, Migasena P. Study on serum bile acids in opisthorchiasis in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1983;66:464–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown AJ, Jessup W. Oxysterols: Sources, cellular storage and metabolism, and new insights into their roles in cholesterol homeostasis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diczfalusy U, Lund E, Lutjohann D, Bjorkhem I. Novel pathways for elimination of cholesterol by extrahepatic formation of side-chain oxidized oxysterols. Scand J Clin Laboratorial Inv. 1996;226:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meaney S, Bodin K, Diczfalusy U, Bjorkhem I. On the rate of translocation in vitro and kinetics in vivo of the major oxysterols in human circulation: critical importance of the position of the oxygen function. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:2130–2135. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200293-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scalia S. Bile acid separation. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1995;671:299–317. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bobeldijk L, Hekman J, de Vries-van der Weij J, Coulier L, Ramaker R, Kleemann R, Kooistra T, Rubingh C, Freidig A, Verheij E. Quantitative profiling of bile acids in biolfluids and tissues based on accurate mass high resolution LC-FT-MS: compound class targeting in metabolomics workflow. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;871:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burkard L, von Eckardstein A, Rentsch KM. Differentiated quantification of human bile acids in serum by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;826:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young ND, Campbell BE, Hall RS, Jex AR, Cantacessi C, Laha T, Sohn W-M, Sripa B, Loukas A, Brindley PJ, Gasser RB. Unlocking the transcriptomes of the carcinogens Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sripa B, Brindley PJ, Mulvenna J, Laha T, Smout MJ, Mairiang E, Bethony JM, Loukas A. The tumorigenic liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini multiple pathways to cancer. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter FD, Scherrer DE, Lanier MH, Langmade SJ, Molugu V, Gale SE, Olzeski D, Sidhu R, Dietzen DJ, Fu R, Wassif CA, Yanjanin NM, Marso SP, House J, Vite C, Schaffer JE, Ory DS. Cholesterol oxidation products are sensitive and specific blood-based biomarkers for Niemann-Pick C1 Disease. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:56ra81. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.