Abstract

Purpose

To develop a new concept for a hardware platform that enables integrated parallel reception, excitation, and shimming (iPRES).

Theory

This concept uses a single coil array rather than separate arrays for parallel excitation/reception and B0 shimming. It relies on a novel design that allows a radiofrequency current (for excitation/reception) and a direct current (for B0 shimming) to coexist independently in the same coil.

Methods

Proof-of-concept B0 shimming experiments were performed with a two-coil array in a phantom, whereas B0 shimming simulations were performed with a 48-coil array in the human brain.

Results

Our experiments show that individually optimized direct currents applied in each coil can reduce the B0 root-mean-square error by 62–81% and minimize distortions in echo-planar images. The simulations show that dynamic shimming with the 48-coil iPRES array can reduce the B0 root-mean-square error in the prefrontal and temporal regions by 66–79% as compared to static 2nd-order spherical harmonic shimming and by 12–23% as compared to dynamic shimming with a 48-coil conventional shim array.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate the feasibility of the iPRES concept to perform parallel excitation/reception and B0 shimming with a unified coil system as well as its promise for in vivo applications.

Keywords: Parallel, excitation, reception, shimming, coil array

Introduction

Major developments in MRI technology have been driven by the ever increasing demand for higher static magnetic field (B0) strengths. This increase, however, has posed many technical challenges, notably larger B0 and radiofrequency (RF) magnetic field (B1) inhomogeneity (1,2). A homogeneous B1 field is required to ensure a uniform excitation across the sample. Recent advances in parallel transmit technology have provided effective means to address this issue by using a process termed RF or B1 shimming, in which the amplitude, phase, timing, and frequency of the RF current in each coil element are independently adjusted (3,4).

A homogeneous B0 field is required to ensure a correct spatial representation of the imaged object. Homogenization of the magnetic field distribution (i.e., B0 shimming) is often a difficult task when strong, localized B0 inhomogeneities are present (5). Passive shimming, which relies on the optimal arrangement of magnetized materials, is limited by the tedious work required and the lack of flexibility in subject-specific conditions (6). On the other hand, active shimming, which utilizes continuously adjustable electromagnets, is the most widely used shimming method and typically employs spherical harmonic (SH) coils (7,8), including the ability to provide dynamic shimming (9). In practice, however, SH shimming often cannot effectively correct for high-order localized field distortions because the required number of coils increases dramatically with the SH order (7). As such, it is typically limited to the second or third order.

Recently, Juchem et al. have proposed a multi-coil modeling and shimming method (10–12), in which a large number of small, localized electrical coils is used to shape the B0 field by independently adjusting the direct current (DC) in each coil, thus achieving an improved performance relative to SH shimming (11,12). However, this approach requires a separate set of shim coils adjacent to the RF coil array, which in turn requires considerable space within the constricted area between the subject and the magnet bore (12). In addition, when the shim coil array is placed within the RF coil array, a large gap is needed in the shim coil array to allow RF penetration and to reduce the electromagnetic interference between both arrays (i.e., RF damping), which reduces the flexibility and performance of the shimming (12).

Here, we propose a new concept for a hardware platform that enables integrated parallel reception, excitation, and shimming (iPRES) with a unified coil system to address these limitations, and perform proof-of-concept phantom experiments with a two-coil array and in vivo simulations with a 48-coil array to demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.

Theory

The proposed iPRES concept is to implement parallel excitation/reception and B0 shimming by employing a single set of localized coils, with each coil simultaneously working in both an RF mode for excitation/reception and a DC mode for B0 shimming. The DC mode is integrated into each coil element of a conventional RF coil array by modifying its circuit to create a closed loop and enable a DC current to flow, thereby generating additional B0 fields that can be used for B0 shimming. This concept is based on the simple principle in electronics that currents at different frequencies can coexist independently in the same circuit with no electromagnetic interference between them (13,14).

This modification does not compromise the design characteristics of the RF coil array for generating flexible B1 fields, including the coil orientation and geometry and the RF current properties (amplitude, phase, timing, and frequency) in each coil element. Furthermore, previous studies on multi-coil field modeling and shimming (10–12) have shown that the B0 field shaping capability of a shim coil array does not critically depend on the exact number, size, positioning, or geometry of the individual coils as long as a reasonably large number of coils is used (typically 24–48). In particular, flexible B0 fields can be generated even if the coils are all oriented parallel to the B0 field, as would be the case for a conventional RF coil array. This advantage is naturally preserved in a unified coil system, which makes the proposed concept generally applicable to a variety of coil geometries designed for different applications, such as cardiac (15), brain (16), or musculoskeletal (17) imaging.

In its most general form, the iPRES concept can therefore perform multiple coil RF transmission (for B1 shimming), parallel reception, and B0 shimming with the same coil array, which may be desirable for specific ultra-high field applications. For other applications (e.g., at 3T and below), it may be preferable to use separate transmit and receive coil arrays, for example to minimize the local specific absorption rate and maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In this case, the iPRES concept can still be applied by adding the B0 shimming capability to the receive array. Such an implementation may be more practical as it would require fewer modifications to the architecture of state-of-the-art MRI systems.

Methods

Proof-of-Concept Implementation with a Two-Coil Array

To demonstrate the feasibility of the iPRES concept without loss of generality, proof-of-concept experiments were performed with a two-coil array designed for concurrent RF excitation/reception and B0 shimming. Two RF coil prototypes were designed and built based on an 11×11 cm figure-8 surface coil and an 11×11 cm single-loop surface coil.

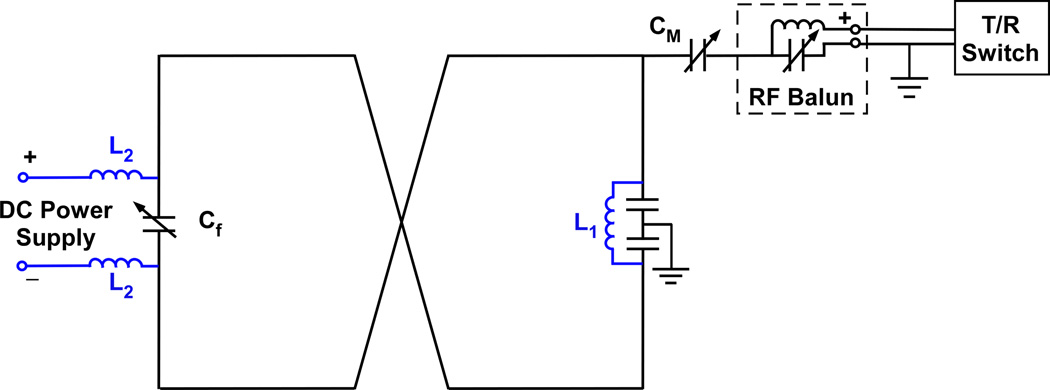

Fig. 1 shows a schematic circuit of the modified figure-8 coil. The addition of an inductor L1 to the original circuit forms a closed loop and allows a DC current to circulate in the figure-8 pathway, thereby generating an additional B0 field that can be used for B0 shimming. A DC power supply is fed into the circuit across the frequency-tuning capacitor. As a result, both the RF and DC currents can circulate in the same coil simultaneously with no interference between them.

FIG. 1.

Schematic circuit of the modified figure-8 coil. The addition of an inductor L1 in conjunction with a DC power supply forms a closed DC loop and allows a DC current to circulate in the figure-8 pathway. The inductors L2 prevent the propagation of RF currents. The RF balun reduces RF coupling between the coil and the surrounding. Cf and Cm are tuning and matching capacitors, respectively.

With a parallel LC circuit, the figure-8 coil becomes a dual-tuned RF coil with a high and a low resonance frequency (18), but with no degradation in performance as compared to the original coil. In our implementation, L1 was chosen to be 2.6 µH, resulting in a low resonance frequency of 28 MHz and a high resonance frequency of 131 MHz, which is close to the original resonance frequency of 128 MHz (at 3T) and makes it easy to tune and match the circuit.

To reduce the electromagnetic coupling between the coil and the MRI system environment, an RF balun was placed between the RF matching circuit and the transmit/receive switch. In addition, to prevent RF power from leaking through the extended DC loop, two inductors L2 of 2.5 µH were placed as RF chokes between the DC loop and the DC power supply. A similar design was applied to the single-loop coil and can also be applied to other types of coils.

The coils were tuned and matched with an HP 4396A network analyzer (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA). Their quality factor remained the same as that of the original coils. The DC loops of both coils were connected in parallel to an HP E3631A DC power supply (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) with a maximum output of ±25 V and 1 A. An adjustable resistor (0–25 Ω) and a switch were inserted into each DC loop, so that the amplitude and direction of the DC current in each coil could be independently adjusted.

Phantom Experiments

All experiments were conducted on a 3T Excite MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Both coils were positioned in a coronal plane on top of a square water phantom containing a grid. The coils were partially overlapped for RF decoupling and the figure-8 coil was placed on top of the single-loop coil, with its two halves along the right/left direction. Second-order shimming using the SH shim coils of the scanner was first performed to obtain a uniform B0 field.

Linear or nonlinear B0 inhomogeneities were then deliberately introduced in the phantom by offsetting the linear shims of the scanner or by placing a stack of 20 coins (US quarters) on top of the figure-8 coil, respectively. The optimal DC currents to be applied in each coil to shim these B0 inhomogeneities were then determined as follows. First, two B0 maps were acquired, as described below, with a DC current of 130 mA applied in either the single-loop coil or the figure-8 coil, but with no linear shim offsets and no coins. Second, two B0 maps were acquired with no DC current in the coils, but with either the linear shim offsets or the coins. The optimal DC currents for B0 shimming were then determined by minimizing the residual field between a weighted combination of the first two B0 maps and either one of the latter two B0 maps.

Coronal B0 maps of the phantom were acquired with a gradient-echo sequence and with repetition time (TR) = 1 s, echo time (TE) = 4.7/5.7 ms, field-of-view (FOV) = 15×15 cm, matrix size = 128×128, and slice thickness = 4 mm. B0 maps were computed from the phase images acquired at both TEs. Coronal images were also acquired with a spin-echo single-shot echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence and with TR = 2 s, TE = 60 ms, FOV = 15×15 cm, matrix size = 128×128, slice thickness = 4 mm, and frequency direction = right/left or superior/inferior. The distance between the figure-8 and single-loop coils and the slice of interest was 4 and 3 cm, respectively. Since our scanner does not have parallel transmit capability, the data were acquired sequentially by exciting only one coil at a time. The images from both coils were then combined by using the square root of the sum of squares method.

In vivo Simulations

Numerical simulations of the B0 field were also performed by using a 48-coil (receive-only) array and a three-dimensional B0 map acquired in the human brain to further investigate the feasibility of the iPRES concept for in vivo applications and to compare it with the conventional multi-coil shimming strategy (12). To this end, we studied a healthy volunteer, who provided written informed consent as approved by our Institutional Review Board, on our 3T scanner. After 2nd-order shimming using the SH shim coils of the scanner, axial images of the whole brain were acquired with a 4-shot spiral asymmetric spin-echo sequence and with TR = 5 s, TE = 24 ms, ΔTE = 0/1/2 ms, FOV 21×21 cm, matrix size = 70×70, slice thickness = 3 mm, and 40 slices. A B0 map was then computed from the phase images acquired at the different ΔTEs.

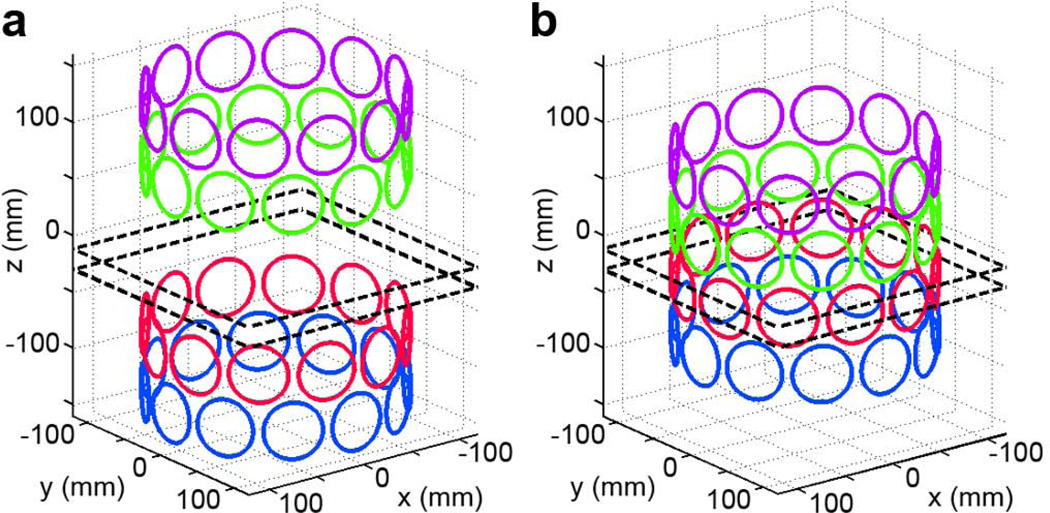

To ensure a fair comparison between the conventional shim coil array and the iPRES coil array, a coil geometry similar to that used in (12) was chosen for both arrays and consisted of four rings of coils arranged on a cylinder surrounding the head, with a 22-cm ring diameter and 5-cm spacing between neighboring rings (Fig. 2). Each ring contained 12 circular single-loop coils with a 5-cm diameter. For the conventional shim coil array (a), the four rings were split into two sets of two rings, with a central 10-cm gap in-between to allow RF penetration and to reduce the RF damping caused by the presence of the shim coil array between the RF coil array and the subject (12). For the iPRES coil array (b), such a gap was not necessary, but four rings of coils were still used (rather than six) in order to maintain the same number of degrees of freedom for B0 shimming. Although the coil array used in (12) consisted of multiple-turn coils, the simulations were performed with single-loop coils and the resulting B0 maps simply scaled by the number of turns.

FIG. 2.

Conventional shim coil array (a) and iPRES coil array (b) used in the simulations. Each ring of coils is drawn in a different color for clarity. The dashed lines denote the location of the two axial slices shown in Fig. 6.

For each coil array, the Biot-Savart law was used to compute a three-dimensional map of the z-component of the magnetic field generated by applying a DC current of 1 A in one coil at a time, resulting in 48 B0 maps. The optimal DC currents to be applied in each coil to shim the brain were then determined by minimizing the residual field between a weighted combination of these 48 B0 maps and the B0 map acquired in vivo. This optimization was performed separately for each axial slice to simulate dynamic shimming. Finally, the B0 map obtained after dynamic shimming was derived by scaling the 48 B0 maps with the optimal DC currents and subtracting them from the B0 map acquired in vivo. All computations were performed in Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Results

Phantom Experiments

Fig. 3 shows B0 maps in a 6×6 cm region-of-interest (ROI) acquired with a DC current of 130 mA applied in one coil at a time. These results show that the modified single-loop and figure-8 coils can both generate a non-uniform B0 field, but with a very different spatial pattern, which can be used for B0 shimming.

FIG. 3.

B0 maps acquired with a DC current of 130 mA applied either in the single-loop coil (a) or in the figure-8 coil (b), after subtraction of the baseline B0 map acquired with no DC current.

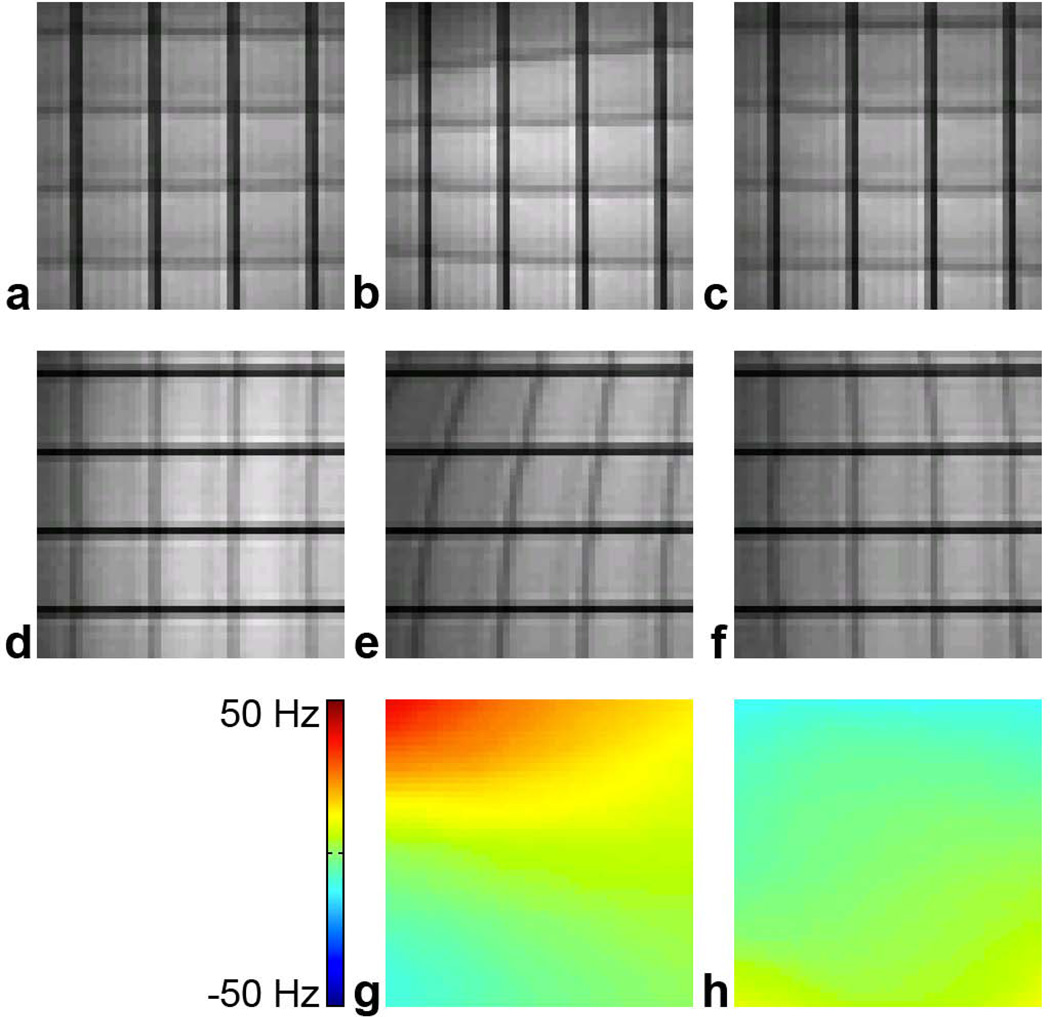

Fig. 4 shows representative EPI images and B0 maps in a 6×6 cm ROI acquired under three conditions. First, images were acquired without DC currents, resulting in minimal geometric distortions (a,d). Second, the linear y-shim (anterior/posterior) and z-shim (superior/inferior) were offset by 5 and 17 (arbitrary units), resulting in a global B0 offset and a linear B0 gradient along z (g) as well as a stretching (b) or shearing (e) of the EPI images. Third, individually optimized DC currents of 228 and 80 mA were applied in the single-loop and figure-8 coils, respectively, resulting in a significant reduction of these B0 inhomogeneities (h) and distortions (c,f). The B0 root-mean-square error (RMSE) was reduced by 80.7% from 19.14 to 3.69 Hz.

FIG. 4.

Reduction of linear B0 inhomogeneities. EPI images with frequency direction = right/left (horizontal) (a–c) or superior/inferior (vertical) (d–f) and B0 maps (g–h) acquired with no linear shim offsets and no DC currents (a,d), with linear shim offsets and no DC currents (b,e,g), or with linear shim offsets and optimal DC currents (c,f,h). The baseline B0 map acquired with no linear shim offsets and no DC currents was first subtracted from those acquired with the other two conditions to yield the B0 maps shown in (g,h).

Fig. 5 shows representative EPI images and B0 maps in a 6×6 cm ROI acquired under three conditions. First, images were acquired without DC currents, resulting in minimal distortions (a,d). Second, a stack of coins was placed in the left-superior quarter of the figure-8 coil, resulting in a strong, localized nonlinear B0 inhomogeneity (g) and nonlinear distortions in the EPI images (b,e). Third, individually optimized DC currents of −278 and 280 mA were applied in the single-loop and figure-8 coils, respectively, resulting in a significant reduction of these B0 inhomogeneities (h) and distortions (c,f). The B0 RMSE was reduced by 61.9% from 12.39 to 4.72 Hz.

FIG. 5.

Reduction of localized nonlinear B0 inhomogeneities. EPI images with frequency direction = right/left (horizontal) (a–c) or superior/inferior (vertical) (d–f) and B0 maps (g–h) acquired with no coins and no DC currents (a,d), with coins and no DC currents (b,e,g), or with coins and optimal DC currents (c,f,h). The baseline B0 map acquired with no coins and no DC currents was first subtracted from those acquired with the other two conditions to yield the B0 maps shown in (g,h).

In vivo Simulations

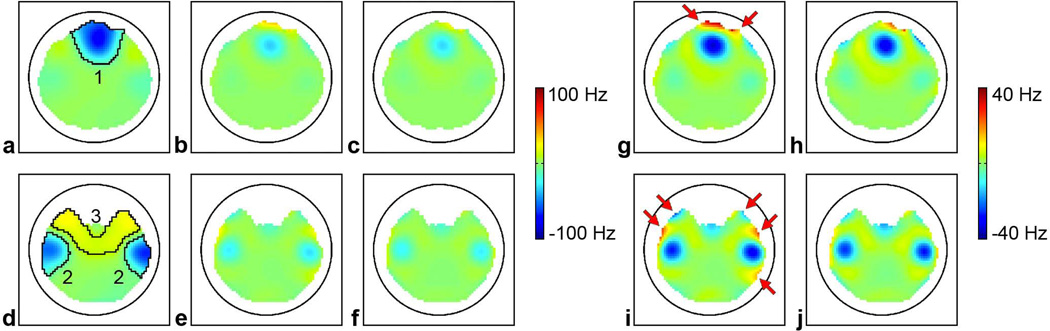

Fig. 6 shows representative B0 maps in two axial slices through the prefrontal cortex and temporal lobes, which are affected by severe B0 inhomogeneities. As expected, static 2nd-order SH shimming alone cannot shim these localized B0 inhomogeneities (a,d). In contrast, dynamic shimming with either the conventional shim coil array (b,e) or the iPRES coil array (c,f) can significantly reduce the B0 inhomogeneity in these regions. However, the iPRES coil array can generate more localized magnetic fields and hence achieve a more effective shimming than the conventional shim coil array (e.g., in the areas indicated by arrows), since it does not require a gap to reduce the RF damping and thus allows the coils to be positioned close to the subject even for central slices, which are typically affected by strong B0 inhomogeneities. Dynamic shimming with the iPRES coil array can reduce the B0 RMSE in the ROIs shown in Fig. 6 by 65.9–78.8% as compared to static 2nd-order SH shimming alone and by 12.1–22.7% as compared to dynamic shimming with the conventional shim coil array (Table 1). The average and maximum DC currents for all coils and for the shimming of all brain slices were 0.52 and 4.05 A for the conventional shim coil array and were 0.38 and 2.37 A for the iPRES coil array, which represents an efficiency (i.e., B0 amplitude per unit current) gain of 1.4 and 1.7, respectively.

FIG. 6.

B0 maps in two axial slices through the prefrontal cortex (a–c) and temporal lobes (d–f) after static 2nd-order SH shimming alone (a,d) or after additional dynamic shimming with the conventional shim coil array (b,e) or the iPRES coil array (c,f). The circle denotes the location of the coil array. The maps shown in (g,h,i,j) are the same as those shown in (b,c,e,f), respectively, but with a different scaling to highlight the differences between the two setups.

Table 1.

B0 RMSE (Hz) in the ROIs shown in Fig. 6

| ROI | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| static 2nd-order SH shimming | 19.46 | 17.54 | 8.87 |

| static 2nd-order SH shimming + dynamic shimming with the conventional shim coil array | 6.75 | 6.81 | 2.43 |

| static 2nd-order SH shimming + dynamic shimming with the iPRES coil array | 5.65 | 5.99 | 1.88 |

Discussion

Our phantom experiments demonstrate that the RF and DC modes of the modified single-loop and figure-8 coils can work simultaneously with no interference between each other and that the DC mode can be used for B0 shimming by individually optimizing the DC current in each coil. Although our proof-of-concept two-coil array only provides relatively limited flexibility for B0 shimming, our simulations based on a 48-coil array show that a full implementation of the iPRES concept with a larger number of coils can generate flexible B0 fields to shim various brain regions affected by B0 inhomogeneities without reducing the B0 homogeneity in other areas, thereby suggesting its feasibility for in vivo applications.

Comparison with Conventional Shimming Methods

The proposed iPRES concept benefits from a number of advantages over existing shimming methods. Our simulations show that it can achieve a more effective B0 shimming than both static 2nd-order SH shimming, by using a large number of localized coils, and conventional multi-coil shimming (12), by eliminating the need to use separate coil arrays for excitation/reception and B0 shimming, thereby avoiding the RF damping effect and allowing the coils to be positioned close to the subject for all slices.

In addition, the iPRES coil array provides greatly improved RF performance relative to the conventional shim coil array. First, the presence of a separate shim coil array between the RF coil array and the subject was found to result in a uniform B1 damping of 15–20% for a human shim coil array with a 10-cm gap in the middle (12) and up to a factor of 2 for a mouse shim coil array with no gap (10). Second, using a separate shim coil array inside the RF coil array increases the distance between the RF coils and the subject by at least a few centimeters, which further reduces the RF sensitivity throughout the whole coil volume. More importantly, since the SNR gain achieved by increasing the number of coil elements in a coil array is highest within a few centimeters of the coil surface, the major benefit of a dramatic increase in peripheral SNR, particularly for parallel imaging, is largely sacrificed (19,20).

In our simulations, a coil geometry similar to that used in (12) was chosen to ensure a fair comparison between both coil arrays. However, further improvements in B0 shimming and/or RF performance may be achieved by using other coil geometries, such as a helmet coil array (16) with coils positioned closer to the head. Finally, the iPRES coil array not only provides improved B0 shimming and RF performance, but can also simplify the scanner design and save valuable space within the magnet bore.

In our simulations of the conventional shim coil array, the maximum DC current was over an order of magnitude smaller than that reported in (12) (0.662 A for 100-turn coils). This discrepancy can be explained by the following reasons: the difference in field strength (3T vs. 7T); the fact that the B0 maps were acquired after static 2nd-order SH shimming in our simulations, but not in (12); the fact that dynamic shimming was performed on individual 3-mm slices in our simulations, but on 9-mm slabs in (12); anatomical differences across subjects; slight variations in coil geometry; and possible differences in the optimization algorithm and convergence criterion.

Technical Considerations

While our proof-of-concept iPRES coil array used home-made inductors L1 with an inductance of 2.6 µH, future implementations can use smaller commercial inductors with an inductance reduced to a few hundreds of nH, which is similar to what is used in conventional RF coil arrays (18). For example, a reduction of L1 to 260 nH and a corresponding doubling of the tuning capacitance will result in the same resonance frequency. Furthermore, the inductors L2 can be placed away from the coil and the subject. As such, none of these inductors will impact the local B0 homogeneity in the subject.

In our simulations of the iPRES coil array, the DC currents were on the order of 1 A. If needed, the maximum current can be limited by using constrained fitting to compute the currents. The DC resistance of each DC loop can be on the order of 1 mΩ. For example, a circular loop with a 5-cm diameter made of a 0.5-mm thick and 5-mm wide copper tape has a DC resistance of 1 mΩ. The inductor L1 can use a power inductor with a DC resistance also on the order of 1 mΩ. Assuming that the total DC resistance of each coil is 10 mΩ, the power generated in a coil by a DC current of 1 A is only 10 mW. Furthermore, in dynamic shimming, both the maximum current and the individual coil carrying that current can largely vary for different slices. In addition, the time-averaged power can be significantly reduced by applying the DC currents only between the excitation and data acquisition of each slice rather than continuously. Therefore, the DC currents are not expected to create any heating issues and active cooling will not be necessary.

Since the iPRES coil array consists of single-turn coils with a relatively small diameter, the Lorentz force generated by a DC current of 1 A on each coil (which is proportional to the current and the number of turns) and the corresponding torque (which is proportional to the force and the coil radius) would be several orders of magnitude smaller than those experienced by gradient coils, which are multiple-turn coils with a total winding length of several hundred meters and currents on the order of a few hundred amperes. Therefore, such forces are not expected to impact the mechanical stability and reliability of the proposed method.

When implementing the iPRES concept in a receive-only coil array, detuning of the RF coil elements will be required and can be achieved without interfering with the DC current used for B0 shimming by adding a DC-blocking capacitor to a conventional active detuning circuit (Fig. S1). Other detuning strategies may also be possible.

Conclusions

A new concept for a hardware platform that enables integrated parallel reception, excitation, and shimming was proposed in this study. Proof-of-concept phantom experiments were performed with a two-coil array designed for concurrent RF excitation/reception and B0 shimming to demonstrate its feasibility. Numerical simulations were further performed with a 48-coil array and B0 maps acquired in the human brain to confirm its utility for future in vivo applications and to demonstrate its advantages over conventional shimming methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Cecil Charles for his suggestions and help with building the RF coils, Dr. Chunlei Liu for stimulating discussions about the multi-coil shimming method, and Dr. Todd Harshbarger for valuable comments on the manuscript. H. Han also thanks Dr. Bruce Balcom and colleagues at the University of New Brunswick MRI Centre for useful knowledge acquired. This work was supported by grants R01EB012586 (to TKT) and R01EB009483 (to AWS) from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Blamire AM. The technology of MRI — the next 10 years? Brit J Radiol. 2008;81:601–617. doi: 10.1259/bjr/96872829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein MA, Huston J, Ward HA. Imaging artifacts at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:735–746. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaughan T, DelaBarre L, Snyder C, Tian JF, Akgun C, Shrivastava D, et al. 9.4T human MRI: preliminary results. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1274–1282. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setsompop K, Wald LL, Alagappan V, Gagoski B, Hebrank F, Fontius U, Schmitt F, Adalsteinsson E. Parallel RF transmission with eight channels at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1163–1171. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch KM, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Optimization of static magnetic field homogeneity in the human and animal brain in vivo. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2009;54:69–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson JL, Jenkinson M, Jezzard P. Optimization of static field homogeneity in human brain using diamagnetic passive shims. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:906–914. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golay MJ. Field homogenizing coils for nuclear spin resonance instrumentation. Rev Sci Instrum. 1958;29:313–315. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romeo F, Hoult DI. Magnet field profiling: analysis and correcting coil design. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1:44–65. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Graaf RA, Brown PB, McIntyre S, Rothman DL, Nixon T. Dynamic shim updating (DSU) for multislice signal acquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:409–416. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juchem C, Nixon TW, McIntyre S, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Magnetic field modeling with a set of individual localized coils. J Magn Reson. 2010;204:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juchem C, Brown PB, Nixon TW, McIntyre S, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Multi-coil shimming of the mouse brain. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:893–900. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juchem C, Brown PB, Nixon TW, McIntyre S, Boer VO, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Dynamic multi-coil shimming of the human brain at 7 T. J Magn Reson. 2011;212:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz P, Hill W. The art of electronics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Martin J, Wu J, Wang H, Promislow K, Balcom BJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of water content across the Nafion membrane in an operational PEM fuel cell. J Magn Reson. 2008;193:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gräßl A, Renz W, Hezel F, Frauenrath T, Pfeiffer H, Hoffmann W, Kellman P, Martin C, Niendorf T. Design, evaluation and application of a modular 32 channel transmit/receive surface coil array for cardiac MRI at 7T. Proceedings of the ISMRM 20th Annual Meeting; Melbourne. 2012. p. 305. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggins GC, Triantafyllou C, Potthast A, Reykowski A, Nittka M, Wald LL. 32-channel 3 Tesla receive-only phased-array head coil with soccer-ball element geometry. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:216–223. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraff O, Bitz AK, Dammann P, Susanne C, Ladd SC, Ladd ME, Quick HH. An eight-channel transmit/receive multipurpose coil for musculoskeletal MR imaging at 7 T. Med Phys. 2010;37:6368–6376. doi: 10.1118/1.3517176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha S, Hamamura MJ, Nalcioglu O, Muftuler LT. A PIN diode controlled dual-tuned MRI RF coil and phased array for multi nuclear imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:2589–2600. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/9/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright SM, Wald LL. Theory and application of array coils in MR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 1997;10:394–410. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199712)10:8<394::aid-nbm494>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiesinger F. Ph.D. thesis. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich; 2005. Parallel magnetic resonance imaging: potential and limitations at high fields. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.