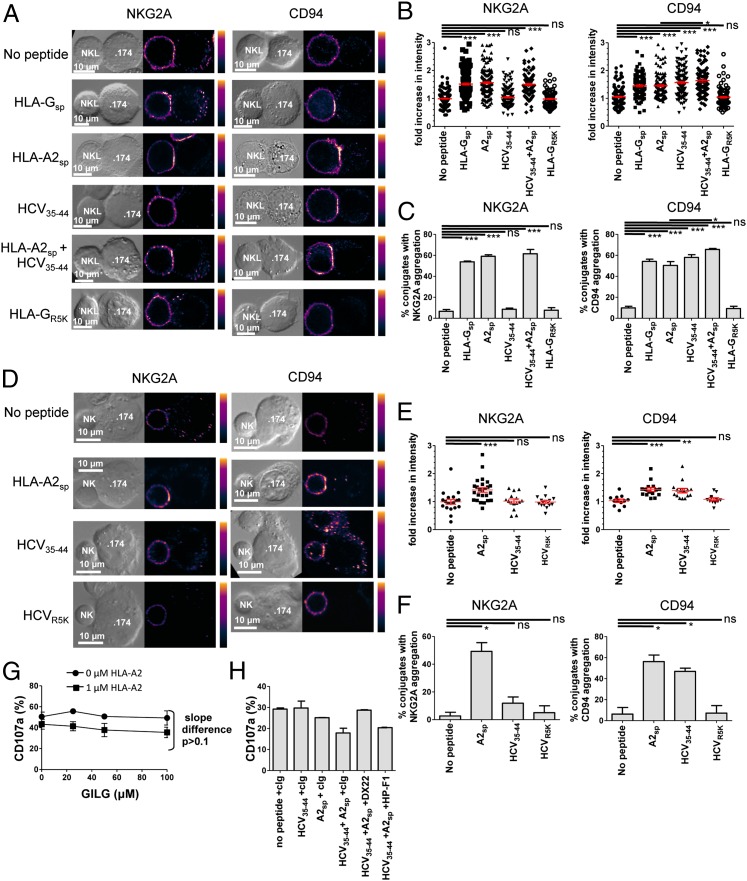

Fig. 3.

HCV core35–44 induces aggregation of CD94 but not NKG2A at the interface between NK and target cells. (A) Comparison of NKG2A (Left) and CD94 (Right) clustering at the interface between NKL effector and .174 target cells, loaded with the indicated peptides. (B) Fold increase of fluorescence intensity at the interface between NKL and .174 target cells compared with a noncontact area of the NKL plasma membrane. (C) The percentage of conjugates with aggregation at the interface between NK cells and target cells. For B and C 100–150 conjugates were analyzed for each condition. (D–F) Clustering of NKG2A (Left) and CD94 (Right) between primary NK cells and .174 target cells as in A–C. E shows the fold increase in intensity, and F shows the percentage of conjugates with aggregation at the interface between the NK cells and .174 target cells. For each condition 20–30 conjugates were analyzed. (G) Degranulation of CD3− CD56+ NKG2A+ CD158b− NK cells in response to increasing concentrations of the HLA-A2–binding peptide GILGFVFTL (GILG) in the presence or absence of 1 µM HLA-A2sp. (H) Degranulation assay of CD3− CD56+ CD158b− NK cells incubated with .174 cells in the presence or absence of the indicated peptides and antibodies to CD94 (DX22), LILRB-1 (HP-F1), or an isotype control antibody (cIg). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test to compare individual pairs of conditions. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.001; ns, nonsignificant.