Abstract

In 2013, the fifth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD V) will be hosted by the Japanese government. TICAD, which has been held every five years, has played a catalytic role in African policy dialogue and a leading role in promoting the human security approach (HSA). We review the development of the HSA in the TICAD dialogue on health agendas and recommend TICAD’s role in the integration of the HSA beyond the 2015 agenda. While health was not the main agenda in TICAD I and II, the importance of primary health care, and the development of regional health systems was noted in TICAD III. In 2008, when Japan hosted both the G8 summit and TICAD IV, the Takemi Working Group developed strong momentum for health in Africa. Their policy dialogues on global health in Sub-Saharan Africa incubated several recommendations highlighting HSA and health system strengthening (HSS). HSA is relevant to HSS because it focuses on individuals and communities. It has two mutually reinforcing strategies, a top-down approach by central or local governments (protection) and a bottom-up approach by individuals and communities (empowerment). The “Yokohama Action Plan,” which promotes HSA was welcomed by the TICAD IV member countries. Universal health coverage (UHC) is a major candidate for the post-2015 agenda recommended by the World Health Organization. We expect UHC to provide a more balanced approach between specific disease focus and system-based solutions. Japan’s global health policy is coherent with HSA because human security can be the basis of UHC-compatible HSS.

Keywords: Japan, human security concept, health systems strengthening, primary health care, universal health coverage

Introduction

The year 2013 can be a landmark year for global health trends because the 5th Tokyo International Conference on African development (TICAD V) will be held in Yokohama, Japan, followed by a high-level panel on the post-2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDG) agenda in the United Nations [1]. This is expected to cast light on global health in the post-MDG agendas.

Since its first launch in 1993, TICAD, which is co-hosted by the government of Japan, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank, has aimed primarily at promoting policy dialogue on Africa with action-oriented results as opposed to the pump-priming of pledges [2]. Thus far, TICAD has been held every five years with several additional meetings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Brief overview of the TICAD Process

| Year | Title of conferences and meetings | Date | Venue | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | TICAD I First Tokyo International Conference on African Development | October 5–6 | Tokyo, Japan | Co-organizers vowed to resuscitate the decline in development assistance for Africa which had followed the end of the Cold War. |

| “Tokyo Declaration on African Development,” guidelines for African development were adopted. The emphasized priorities are: | ||||

| Importance of ‘Africa’s ownership’ of its development as well as of the ‘partnership’ between Africa and the international community. | ||||

| Harnessing of Asian experience for the benefit of African development. | ||||

| 1998 | TICAD II Second Tokyo International Conference on African Development | October 19–21 | Tokyo, Japan | Primary Theme: Poverty Reduction and Integration into the Global Economy |

| “African Development Towards the 21st Century: the Tokyo Agenda for Action” was adopted. | ||||

| Ownership and partnership were the underlying principles. | ||||

| Expressed commitment to the agreed goals and priority actions in the following areas: | ||||

| Social development: education, health and population, and other measures to assist the poor. | ||||

| Economic development: private sector development, industrial development, agricultural development, external debt. | ||||

| Foundations for development: good governance, conflict prevention and post-conflict development. | ||||

| 2001 | TICAD Ministerial Meeting | December 3–4 | Tokyo, Japan | Substantive discussions took place on TICAD II review and on NEPAD (the New Partnership for Africa’s Development), the development initiative by African people themselves. |

| 2003 | TICAD III Third Tokyo International Conference on African Development | September 29–October 1 | Tokyo, Japan | Succeeded in bringing together international support for African development, NEPAD in particular, and expanding partnership within the international community. In addition, at TICAD III priority challenges were specified in the various development areas, and a new initiative toward future African development was adopted. |

| The three pillars of Japan’s assistance for Africa was announced including “human centered development”, “poverty reduction through economic growth” and “consolidation of peace”. | ||||

| “The TICAD Tenth Anniversary Declaration,” which confirmed approaches to development including consolidation of peace and human security was adopted. | ||||

| 2008 | TICAD IV Fourth Tokyo International Conference on African Development | May 28–30 | Yokohama, Japan | “Yokohama Declaration” accompanied by “Yokohama Action Plan” was adopted. |

| Action to be taken by 2012 was described in “Yokohama Action Plan”. | ||||

| 2010 | Second TICAD Ministerial Follow-up Meeting | May 2–3 | Arusha, Tanzania | Discussion focused on progress in the implementation of the Yokohama Action Plan as TICAD IV follow-up, as well as MDGs. |

| 2011 | Third TICAD Ministerial Follow-up Meeting | May 1–2 | Dakar, Senegal | Political and financial issues in Africa were also discussed. |

| 2012 | Fourth TICAD Ministerial Follow-up Meeting | May 5–6 | Marrakech, Morocco | The “Kan commitment” was mentioned. |

| 2012 | TICAD V Preparatory Senior Officials’ Meeting | Nov 15–17 | Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso | Remaining development challenges including MDGs were mentioned. |

The items were modified from the web http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad/meeting.html (accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

TICAD has played a leading role in promoting the human security concept in policy dialogue on Africa. As stated above, TICAD is not a pledge conference, thus it may not be appropriate to evaluate it from the financial aspect. It is, however, necessary to examine the relationship between global health and TICAD to understand its catalytic function.

In this article, we briefly review the development of the human security concept in the TICAD health agenda dialogue, and finally recommend a role for TICAD in the integration of the human security concept in the post-2015 agenda.

Agenda on health and integration of human security in the TICAD dialogue

Looking back on TICAD’s dialogue, health in Africa has not been the main agenda. Its momentum in relation to health has grown gradually.

In the Tokyo declaration adopted in TICAD I (1993), health was treated as an ad-hoc topic. The statement mentioned that investment priority should be given to nutrition, health, and education with special reference to the improvement of the situation of woman and children. In addition, the threat posed by the HIV/AIDS pandemic was recognized [3].

In TICAD II (1998), the statement items in “Towards the 21st century,” included health through all life stages and an increase of access to primary health care [4].

The term “Human Security” was first adopted in TICAD III [5]. In the Chair’s summary of TICAD III, the three pillars of Japanese assistance in Africa were announced including: “human centered development,” “poverty reduction through economic growth,” and “consolidation of peace.” Under the item “human centered development,” besides underscoring the seriousness of HIV/AIDS as one of the most serious threats to African development and the serious impact of tuberculosis, malaria, and polio, the importance of primary health care (PHC), and the development of a regional health system as well as health education to deal with infectious diseases was recognized.

The year 2008 was a very special year for global health trends because the G8 Toyako Summit, Japan and the TICAD IV were both co-hosted by the Government of Japan. A strong momentum for global health that focused on Africa was developed and which kept MDGs 4, 5, and 6 high on the agenda. The momentum was developed by the Takemi Working Group (TWG), which was chaired by Prof. Keizo Takemi [6]. The high-level working group, which was comprised of scholars, government officials, and practitioners from a diverse range of sectors in Japan, was managed by the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE). The group held several dialogues on global health. The TWG membership included officers from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which is in charge of handling Japan’s overseas domestic aid activities, alongside officers from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Over the course of dialogues, focus was set primarily on Sub-Saharan Africa because the Millennium Development Goals Report, 2007 revealed that Sub-Saharan African countries had fallen far behind in the achievement of MDG 4, 5, and 6 [6]. At that time, since health systems strengthening was considered a key to empowering individuals and communities [7], the focus of the topic gradually evolved to health system strengthening with human security. The TWG proposed several recommendations to the Government of Japan that emphasized these two points of focus [7, 8]. In TICAD IV, their recommendations were also reflected in the “Yokohama Action Plan,” which indicated that the TICAD process should focus on the notion of “human security” for the achievement of the MDGs [9].

In the TICAD V Preparatory Senior Officials’ Meeting held in Burkina Faso (November, 2012), which was attended by the delegations of African countries and TICAD co-organizers (the Government of Japan, the African Union Commission, the United Nations, the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank), participants commended African countries for having achieved remarkable economic and social development, but stressed that they are still faced with various development challenges, including growing economic disparity and insufficient progress towards achieving the MDGs [10].

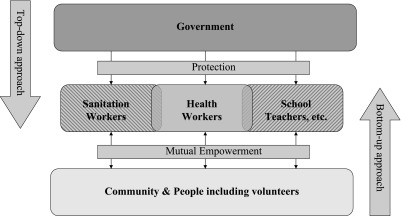

The relevance of human security to health system strengthening

The human security approach has particular adaptability with regard to the promotion of health system strengthening because of its focus on comprehensive health care services for improving the health and wellbeing of individuals and communities [11]. Human security builds on two kinds of mutually reinforcing strategies: protection and empowerment. Protection shields people from dangers, while empowerment enables people to develop their potential and to participate fully in decision-making [12]. According to the Takemi schema (Fig. 1) of health system strengthening in Japan’s post World War II period [13], protection equates to a top-down approach. Empowerment, in contrast, is a bottom-up approach. The top-down approach can be made by central or local governments, while the bottom-up approach can be achieved by individuals and communities. Both are therefore required in a variety of situations and are mutually reinforcing. The Takemi schema is a dual approach in that it is both top-down and bottom-up and as such aims to protect communities as it empowers [13]. Tall and Jimba modified this dual approach into a model that fits the situation of Africa, with a structure that is almost same as the Takemi schema [14].

Fig. 1.

Takemi’s schema on health system strengthening—Two sided strategy—

Source: Modified from Takemi K. Japan’s Role in Global Health and Human Security. 2008. http://www.jcie.or.jp/cross/globalhealth/cgh-jc01.pdf

The government of Japan has made global health a high priority in its foreign policy agenda and it has been among the strongest advocates for human security.

The government of Japan thus welcomed the TWG recommendation. Interestingly, in the Kyushu-Okinawa G8 summit held in 2000, infectious diseases were picked up as a threat with the potential to reverse decades of development and rob an entire generation of hope for a better future, upholding the importance of human security [15]. The Japanese foreign minister of the day declared Japan’s commitment to the support of global health through the human security approach with a mention of the vital importance of not only focusing on the health and protection of individuals, but also striving to empower individuals and communities through the strengthening of health systems [7, 16].

In February 2008, the G8 health experts group (GHEG) meeting was organized among G8 member countries. In its dialogue process, respect for human security was affirmed and its importance for global health was stipulated in the report entitled “Toyako Framework for Action on Global Health,” which was welcomed by the chair’s summary of G8 Toyako Summit [17, 18].

The post-2015 agenda

Now that the year 2015 is approaching, the post-2015 agenda should be carefully considered. Universal health coverage (UHC) is, thus far, a major candidate for the post-2015 agenda since the WHO emphasizes its importance as a single overarching health agenda that makes sense [19]. We support this recommendation because UHC is deemed to be able to provide a more balanced approach between specific disease focus and system-based solutions including PHC [20], and the human security approach would be more effective for covering vulnerable groups that have been excluded from UHC and for fragile countries with weak health systems. One of the weaknesses of PHC is the legacy that the system failed to integrate HIV/AIDS care, which was a major component of MDG 6. We expect UHC to essentially be PHC with HIV/AIDS countermeasures (MDG 6). If MDG 6 is successfully integrated into PHC by UHC, it would make PHC the winning method for integrating health system strengthening with regard to MDGs 4, 5, and 6.

One of major success stories with regard to UHC is Japan. Its successes have been detailed and analyzed in several articles [21–23]. Many factors are suggested to have contributed to the establishment of UHC and improvement of health of Japanese people including public health policies, high literacy and education levels, traditional diet and exercise, economic growth, and a stable political environment with a social, democratic movement [22–24]. In the period following World War II until the mid-1960s, Japan reduced mortality rates due to infectious diseases in children under the age of five and of adult mortality due to tuberculosis. While improvement of nutrition and environmental conditions are primary contributors to health, we speculate that the “selection and concentration strategy” contributed strongly to this success after 1961, at which time UHC was launched and treatment costs of patients with TB were treated as a public expense [25]. As the Takemi schema shows, while local health workers made a conscious effort to deliver services to community people based on the egalitarian principles of treatment, the central government developed the strategy of nationwide utilization of UHC [25]. However, we should keep in mind that, in spite of Japan’s success with regard to UHC development, the country still faces its own challenges. With its rapidly aging society and the burden of the Great East Tohoku disasters, UHC in Japan is losing its affordability to all people and has required structural reform [26].

The introduction of UHC to global health needs to be considered a dynamic issue and it would be very difficult to provide a one size fits all solution for impoverished countries in Africa and beyond. Africa has its own unique health problem with the high level of HIV/AIDS [27]. In addition to the burden of HIV/AIDS, recent reports indicate that the number of people with undiagnosed hypertension and diabetes is greater than the number of people living with HIV/AIDS [28, 29]. Japan’s healthcare challenge is that it must adapt to the pressures of a rapidly aging population. In this regard, we see some similarity as to the issues that must be tackled. Thus, we recommend the UHC for the post-2015 agenda. The lessons Japan has learned from tackling the dynamic challenges of its aging population would apply well to Africa and provide a good opportunity for mutual learning. As Shibuya et al. pointed out in their four key policy recommendations, reconsidering the meaning of global health in aging populations and identifying areas in which Japan has greater expertise is a key facet of the strategic agenda [26].

In this regard, the series of dialogues in TICAD and subsequent meetings should be respected since we see a clue in the implementation of the human security concept.

It is widely recognized that in order to deliver both preventive and curative healthcare services in an efficient and effective manner, health system strengthening with local ownership, local diagnosis and local capacity building is required. For that purpose, a two-sided strategy is needed to both strengthen the state’s capacity to deliver prevention and curative health services and to empower community-based health workers, volunteers and parents [20]. In Sub-Saharan African countries, in particular, donors and partners must coordinate and harmonize their approaches to UHC in order to avoid duplication and fragmentation. Thus, the human security approach should not be an additional effort, it should be integrated into efforts towards UHC.

As Vega pointed out [30], for the achievement of sustainable UHC, two inter-related components are required: access to coverage for necessary health services and access to coverage with financial protection. This challenge can be discussed in the coming TICAD and subsequent meetings with a view to the human security approach (protection and empowerment).

Japan’s global health policy has been consistent from the Okinawa G8 summit in 2000, through the Toyako G8 Summit and TICAD IV in 2008 to TICAD V in 2013 because it has been based on the human security concept with a special emphasis on bottom-up, comprehensive, multi-sectoral, and participatory approaches that allow it to transform legacy PHC into effective UHC.

Challenges to be considered

For the reasons noted above, there is a great opportunity for Japan’s global health policy and its domestic experiences of developing UHC to contribute to Africa. We should, however, consider several challenges with respect to its applicability, sustainability and outcome in the African setting.

First, the applicability of the human security model (Takemi’s dual approach) to Africa should be carefully discussed. The promotion of the human security approach may not be well accepted given the promotion of a rights-based approach by several stakeholders including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund [31], Sweden [32] and the United Kingdom [34]. Although the applicability of the HS model is recognized with a level of expectation [34], it should be a matter of discussion in TICAD V policy dialogues and subsequent meetings. While we see some similarity between the rights-based approach and HSA, including top-down and bottom-up approach [31], we speculate that the rights-based approach, a kind of legal-based and normative approach, may not be effective when “instant choices need to be made between two fundamentally bad options.” In contrast, HSA might assist decision-making by “identifying the least objectionable option” [12]. In addition, we should consider the coherence of UHC with existing social franchising systems and conditional cash transfer [35–37], both of which are considered to be innovative and of great impact to health in Africa. A system of UHC with HSA integrated with social franchising and conditional cash transfer could be recognized as being favorable.

Second, the sustainability of UHC should be considered. Looking back on the history of PHC, the lesson of selective PHC is deemed to be important. Criticisms of PHC included that it was too broad and there were doubts over its feasibility. Selective PHC, which consisted of GOBI (growth monitoring, oral rehydration therapy, breastfeeding, and immunization) approaches, was advocated by UNICEF and supported by several donors. However, the scheme has been criticized for its narrow focus on technocentric approaches [38], which did not encourage community participation and which were unable to take a central position in the global health community. As a result, the PHC concept and its implementation fluctuated and common interest was lost. The sustainability of UHC may be associated with health finance and management capacity, which is another challenge. Once UHC is prioritized and targeted for the post-MDG agenda, it is less likely to fluctuate than PHC. However, the global health community has been swinging like a pendulum from a vertical approach (selective PHC and the MDGs), to a horizontal approach (health system strengthening and PHC). Even if the UHC concept achieves mainstream acceptance among the global health community, the direction of the stream should be carefully monitored through the TICAD dialogue processes and the World Health Assembly agendas, which cover a variety of items but which do not always reflect international health issues in terms of disease burden [39].

Third, the outcomes achieved through TICAD should be considered. As the TICAD monitoring process reported, the renovation of more than 1,000 health facilities and the training of more than 100,000 health workers have already been achieved. These indicators were set in reflection on the “Yokohama Action Plan” and “Toyako Framework for Action on Global Health”. In a sense, Japan may have achieved accountability to the global health community, however these achievements and inputs including an ongoing model project named “EMBRACE” (Ensure Mothers and Babies Regular Access to Care) [40], and education services in poor countries from 2011 to present (continuing to 2015) [41] have been made based on a large amount of donor funds, including Japan’s pledge of US$ 8.5 million at the UN MDG Summit in September 2010, named the “Kan commitment,” from the name of the prime minister of the day [42]. The Kan commitment was not restricted to TICAD actions. The problem, however, is that this achievement came at the cost of such a large amount of input. As noted above, the main objective of TICAD is to promote output-oriented policy dialogue, not the pump-priming of the pledges, which are necessary to sustain high-input programs.

Japan has gained newer accountability for establishing the means by which this achievement can vitalize communities in the light of the human security concept. In the coming TICAD V and follow-up meetings, the direction of policy dialogue should focus on how to bring about outcome and establish accountability in African countries while best utilizing existing outputs along with evaluating the appropriateness and effectiveness of these inputs; even though evaluating outcomes will be difficult due as it will take longer to confirm the actual outcomes.

Conclusion

Japan’s health system experiences and the global health policy presented by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and JICA are consistent with the human security concept. The human security concept can be the basis of health system strengthening, which complements UHC. It is also Japan’s challenge to incorporate PHC into health system strengthening and infectious disease control activities, to strengthen newborn and child health activities, and to contribute to UHC development. In the coming TICAD dialogue, the human security approach should be strengthened with a view to the post-2015 agenda.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Grant of Research on global health issues, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Contribution

Takahashi K and Kobayashi J made a significant contribution to the writing of the manuscript. Nomura M made a significant contribution to the writing of the Table 1. Kakimoto K and Nakamura Y supervised all parts of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Webster PC. What next for MDGs? CMAJ 2012; 184: E931–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Government of Japan, United Nations (OSCAL U, Global Coalition for Africa). Launching of TICAD II Process. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad2/ticad23.html. (Accessed on Feb 8, 2013)

- 3.The Government of Japan. Tokyo Declaration on African Development “Towards the 21st Century”. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad2/ticad22.html. (Accessed on Feb 8, 2013)

- 4.The Government of Japan. Second Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD II). Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad2/ticad22.html. (Accessed on Feb 8, 2013)

- 5.The Government of Japan. Summary by the Chair of TICAD III. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad3/chair-1.html. (Accessed on Feb 8, 2013)

- 6.Japan Center for International Exchange. Challenges in Global Health and Japan’s Contributions. Available from: http://www.jcie.or.jp/cross/globalhealth/overview.html. (Accessed on Feb 12, 2013)

- 7.Takemi K, Jimba M, Ishii S, Katsuma Y, Nakamura Y; Working Group challenges with Global Health and Japan’s contribution. Human security approach for global health. Lancet 2008; 372: 13–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takemi K, Masamine J, Sumie I, Katsuma Y, Nakamura Y. Task Force on “Challenges in Global Health and Japan’s Contribution”. Global Health, Human Security, and Japan’s Contributions. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Center of International Exchange; 2009.

- 9.Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. Yokohama Action Plan. Yokohama, Japan: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; 2008.

- 10.Ministry of foreign affairs J. The TICAD V Preparatory Senior Officials’ Meeting (SOM), Chair’s Summary: Ministry of foreign affairs, Japan, 2012. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/area/ticad/tc5/pdfs/som_1211_01.pdf. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 11.Takemi K, Reich MR. The G8 and Global Health: Emerging Architecture from the Toyako Summit. In: Hubbard S, Ashizawa K, eds. G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit Follow-Up Global Action for Health System Strengthening: Policy Recommendations to the G8 Task Force. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Center for International Exchange; 2009.

- 12.Comission on Human Security. Human Security Now. New York: United Nations, 2003.

- 13.Takemi K. Japan’s Role in Global Health and Human Security. Available from: http://www.jcie.or.jp/cross/globalhealth /cgh-jc01.pdf. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 14.Tall CT, Jimba M. Health and Human Security in Action—Presentation from the Ground. Available from: http://www.jcie.org/japan/j/pdf/csc/ghhs/hhs/ticad/symposium_jimba.pdf. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 15.Kunii O. The Okinawa Infectious Diseases Initiative. Trends Parasitol 2007; 23: 58–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koumura M. Global health and Japan’s foreign policy. Lancet 2007; 370: 1983–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.G8 Health Experts Group. Toyako Framework for Action on Global Health. Tokyo, Japan: United Nations, 2008.

- 18.The Government of Japan. Summary by the Chair of Hokkaido Toyako Summit. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/summit/2008/doc/doc080709_ 09_en.html. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 19.The World Health Organization. Positioning Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda, WHO Discusssion Paper. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/post2015/WHOdiscussionpaper_October2012.pdf. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 20.Reich MR, Takemi K, Roberts MJ, Hsiao WC. Global action on health systems: a proposal for the Toyako G8 summit. Lancet 2008; 371: 865–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda N, Saito E, Kondo N, Inoue M, Ikeda S, Satoh T, Wada K, Stickley A, Katanoda K, Mizoue T, Noda M, Iso H, Fujino Y, Sobue T, Tsugane S, Naghavi M, Ezzati M, Shibuya K. What has made the population of Japan healthy? Lancet 2011; 378: 1094–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reich MR, Ikegami N, Shibuya K, Takemi K. 50 years of pursuing a healthy society in Japan. Lancet 2011; 378: 1051–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikegami N, Yoo BK, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto M, Ogata H, Babazono A, Watanabe R, Shibuya K, Yang BM, Reich MR, Kobayashi Y. Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet 2011; 378: 1106–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKee M, Balabanova D, Basu S, Ricciardi W, Stuckler D. Universal health coverage: a quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value Health 2013; 16: S39–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Japan International Coperation Agency (JICA). Japan’s Experiences in Public Health and Medical Systems. Available from: http://jica-ri.jica.go.jp/IFIC_and_JBICI-Studies/english/publications/reports/study/topical/health/index.html. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 26.Shibuya K, Hashimoto H, Ikegami N, Nishi A, Tanimoto T, Miyata H, Takemi K, Reich MR. Future of Japan’s system of good health at low cost with equity: beyond universal coverage. Lancet 2011; 378: 1265–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. MDG 6: combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/diseases/en/. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 28.United Nations News Center. Hypertension and Diabetes on the Rise Worldwide, Says UN Report 2013. Available from: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?newsid=42012#.UbFHi-eeOEY. (Accessed on May 30, 2013)

- 29.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013.

- 30.Vega J. Universal health coverage: the post-2015 development agenda. Lancet 2012; 381: 179–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United Nations. The Human Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation Towards a Common Understanding Among the UN Agencies. The Interagency Workshop on a Human Rights Based Approach. Geneva: United Nations; 2003.

- 32.Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sweden. Human Rights in Swedish Foreign Policy. Stockholm, Sweden: Government Offices of Sweden; 2009.

- 33.Bluck S. DFID’s Rights Based Approach. Equity and Rights Team, ed. London: DFID; 2006.

- 34.Were M. Human Security Approach in the Health Sector in Africa. Available from: http://www.jcie.org/japan/j/pdf/csc/ghhs/hhs/ticad/symposium_were.pdf. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)

- 35.International Poverty Centre. Cash Transfers: Lessons from Africa and Latin America. Brasilia: UNDP; 2008.

- 36.Schubert B, Slater R.Social cash transfers in low-income African countries: conditional or unconditional? Dev Policy Rev 2006; 24: 571–578 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beyeler N, York De La Cruz A, Montagu D. The impact of clinical social franchising on health services in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8: e60669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cueto M. The origins of primary health care and selective primary health care. Am J Public Health 2004; 94: 1864–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitamura T, Obara H, Takashima Y, Takahashi K, Inaoka K, Nagai M, Endo H, Jimba M, Sugiura Y. World Health Assembly Agendas and trends of international health issues for the last 43 years: Analysis of World Health Assembly Agendas between 1970 and 2012. Health Policy 2013; 110: 198–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Government of Japan. Japan’s Global Health Policy 2011–2015. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; 2010.

- 41.The Government of Japan. Japan’s Education Cooperation Policy 2011–2015. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; 2010.

- 42.Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. The Fourth TICAD Ministerial Follow-up Meeting. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/africa/ticad/min1205/. (Accessed on Apr 15, 2013)