Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to report the long-term remission results from the ConstaTRE relapse prevention trial, in which clinically stable adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder treated with oral risperidone, olanzapine, or oral conventional antipsychotics were randomized to risperidone long-acting injectable (RLAI) or oral quetiapine, dosed according to package-insert recommendations.

Methods:

In the ConstaTRE trial, efficacy and tolerability were recorded for up to 24 months. This post hoc analysis presents remission data, defined, according to the Schizophrenia Working Group criteria, as achieving and maintaining eight core symptoms of schizophrenia that are mild or less over 6 months. Additional secondary outcome measures are also presented.

Results:

A total of 710 patients were randomized to RLAI (n = 355) or quetiapine (n = 355). Mean mode ± standard deviation (SD) drug doses were RLAI 33 ± 10 mg every 2 weeks and quetiapine 413 ± 159 mg daily. Full remission was achieved by 51.1% of patients with RLAI and 39.3% with quetiapine (p = 0.003). Mean ± SD of full remission durations were not significantly different with RLAI (540 ± 181 days) and quetiapine (508 ± 188 days). Overall tolerability was similar between treatment groups.

Conclusions:

Among stable patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, remission was more likely after switching to RLAI than quetiapine.

Keywords: antipsychotics, long-acting injectable risperidone, quetiapine, remission, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic, disabling disease that requires long-term treatment. Remission is increasingly recognized by clinicians and researchers as a particularly important outcome measure when treating schizophrenia and related disorders [Davidson et al. 2008]. The Schizophrenia Working Group has defined remission as achieving and maintaining symptoms of schizophrenia that are mild or less over a 6-month period [Andreasen et al. 2005]. This definition has been utilized in numerous studies investigating schizophrenia outcome [Ciudad et al. 2009; Díaz et al. 2012; Dunayevich et al. 2006; Haynes et al. 2012; Lambert et al. 2010; San et al. 2007; Wunderink et al. 2007].

Unfortunately, effective long-term symptom improvement is often complicated by symptomatic relapse [Schooler, 2006]. Treatment nonadherence is a major risk factor for relapse [Leucht and Heres, 2006], with medication nonadherence affecting nearly half of all outpatients with schizophrenia treated for 1 year [Rosa et al. 2005]. A variety of factors contribute to poor treatment adherence, including poor treatment tolerability [Yamada et al. 2006], poor insight, health beliefs, the patient or family being opposed to medications, problems with treatment access, embarrassment/stigma over illness, no perceived daily benefit, medication interference with life goals, poor therapeutic alliance, complicated treatment regimen, cognitive dysfunction, and lack of social support [Dolder et al. 2002; Kane, 2007; Linden and Godemann, 2007; Löffler et al. 2003].

Medication adherence may be improved by treating patients with long-acting antipsychotic formulations [Kane, 2006; Leucht and Heres, 2006; Schooler, 2003] and selecting better-tolerated atypical antipsychotics compared with conventional neuroleptics [Dolder et al. 2002]. Currently, three long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotics have been developed and have completed randomized controlled clinical trials for the treatment of schizophrenia: risperidone long-acting injectable (RLAI), olanzapine pamoate and paliperidone palmitate [Zhornitsky and Stip, 2012]. An open-label, 50-week RLAI study has evaluated remission using the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria in stable patients converted to RLAI [Lasser et al. 2005]. In this study, all patients were considered clinically stable at baseline; however, 68% were not in remission. After switching to RLAI, 21% of previously nonremitted patients achieved symptom remission for at least 6 months. Remission was also assessed in patients treated in the Switch to Risperidone Microspheres (StoRMi) open-label study following patients switched to RLAI for up to 18 months [Llorca et al. 2008]. In this sample of 529 patients, 94% of those who achieved or maintained remission at 6 months were in remission at endpoint. Among patients not meeting remission criteria at baseline, 45% were in remission at endpoint; among patients meeting remission severity criteria at baseline, 85% were in remission at endpoint. In a small long-term study, 50 patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder were treated with RLAI for 2 years [Emsley et al. 2008a]. Remission was achieved by 32 of the 50 patients (64%).

The 2-year, RLAI relapse prevention trial (ConstaTRE) was designed to compare relapse in stable patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders treated with either RLAI or the oral atypical antipsychotic quetiapine [Gaebel et al. 2010]. The use of nonblinded treatment in this study allows a more real-world evaluation of treatment efficacy as influenced by adherence, rather than a direct efficacy analysis of differences between risperidone and quetiapine. In this study, relapse occurred in 16.5% of patients treated with RLAI and 31.3% with quetiapine. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) time to relapse among patients experiencing a relapse was 244.9 ± 208.0 days with RLAI and 207.6 ± 171.0 days with quetiapine. The mean ± SD relapse-free period was 607.1 ± 11.4 days with RLAI and 532.5 ± 15.6 days with quetiapine. The current report expands on the earlier report by presenting long-term remission results from the ConstaTRE study [Gaebel et al. 2010].

Experimental procedures

Study design

ConstaTRE was a multicentre, open-label, randomized, active-control, 2-year study comparing RLAI and oral quetiapine [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00216476]. This study was conducted from October 2004 to November 2007 at 124 sites in 25 countries. Results of a small descriptive arm in which patients could also be randomized to aripiprazole were described in a separate paper [De Arce Cordón et al. 2012]. This trial was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice, and the study protocol and consent were approved by an Institutional Review Board. Informed, written consent was obtained from all patients prior to study enrolment. A full description of ConstaTRE study methods is described in a previously published report of primary outcome data [Gaebel et al. 2010].

Patients

Eligible patients for this study were adults (aged ≥18 years) with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [American Psychiatric Association, 1994] who were: symptomatically stable; treated with monotherapy with oral risperidone ≤6 mg daily, olanzapine ≤20 mg daily, or a conventional oral neuroleptic (≤10 mg haloperidol or its equivalent); and candidates for switching therapy. Patients were excluded if they had a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or were treated with antipsychotics other than oral risperidone, olanzapine or conventional oral neuroleptics.

Treatment

Treatment recommendations followed approved dosing guidelines for RLAI and quetiapine. Stratified randomization according to previous treatment was used to ensure comparability of treatment arms with regard to previous treatment. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive open-label treatment with RLAI or oral quetiapine for a maximum of 24 months, with doses adjusted based on symptoms and tolerability.

Concomitant treatment with mood stabilizers or antidepressants was permitted if clinically necessary. Anticholinergic medication and benzotropine mesylate were permitted to treat extrapyramidal symptoms. Sedatives were prohibited, except for benzodiazepines for sleep.

Assessments

Assessments were made every 2 weeks throughout the study, using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and Clinical Global Impression – Change (CGI-C) scores. The primary efficacy assessment in ConstaTRE was relapse, which was detailed in a previously published paper [Gaebel et al. 2010]. Remission was a secondary, preplanned and prespecified outcome parameter which was conducted as a post hoc analysis and is the major focus of this report. Remission was defined using criteria proposed by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group [Andreasen et al. 2005] and has been used in previous long-term studies with RLAI [Kissling et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2005]. For full remission, both symptom severity and duration requirements had to be met. Symptomatic severity for remission required: patients to score ≤3 on all eight key PANSS items for negative symptoms (blunted affect, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, and lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation), disorganization (conceptual disorganization and mannerisms/posturing), and psychoticism (delusions, unusual thought content, and hallucinatory behaviour). Duration remission criteria required that the above severity criterion be achieved and fulfilled for ≥6 months regardless of whether or not remission was maintained until the end of the study. Both achievement and maintenance of PANSS scores were evaluated. Additional secondary efficacy outcome measures, not described in the previous report [Gaebel et al. 2010], included changes in MADRS total and individual symptom scores and CGI-C scores.

Safety and tolerability were assessed by recording the occurrence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) at each visit.

Data analysis

All patients treated with at least one dose of study drug were eligible for efficacy and tolerability analyses (intent-to-treat). Time to remission was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method. Comparison of time to remission between RLAI and quetiapine was performed using the log-rank test with alpha of 5%. A hazard ratio (HR) was calculated to estimate the difference in remission risk between RLAI and quetiapine. Demographics, disease characteristics, and adverse events (AEs) were assessed using descriptive analyses. Within-group differences for ordinal/continuous data were assessed using the Wilcoxon two-sample test. Nominal data were tested using the Fisher exact test. All statistical tests were interpreted at the 5% significance level (two-tailed).

Results

The results of the designed prespecified analysis of the ConstaTRE trial after the last enrolled patient completed 1 year of treatment led to the recommendation by independent experts to terminate the trial early due to achieving the predetermined difference in efficacy.

Patients

ConstaTRE included an evaluable sample of 666 patients (329 RLAI and 337 quetiapine). Baseline demographics have been previously described and were similar between treatment groups [Gaebel et al. 2010]. Most patients were male (58.0%), Caucasian (97.6%), and diagnosed with schizophrenia (82.3%), with a median time since diagnosis of 7 years (range 0–66 years).

Among the 666 evaluable patients, 2-year treatment was completed by 45.9% of patients randomized to treatment with RLAI (n = 151) and 35.6%of patients randomized to quetiapine (n = 120). The between-group difference in treatment completion was significant (p = 0.0074). Mean mode ± SD drug doses were 33.6 ± 10.1 mg RLAI every 2 weeks and quetiapine 413.4 ± 159.2 mg daily.

Remission

Efficacy data were available for 327 patients treated with RLAI and 326 treated with quetiapine.

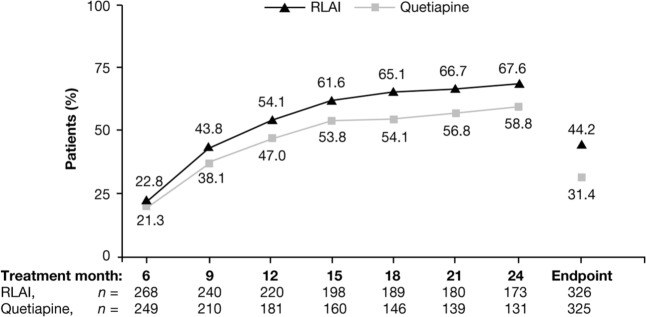

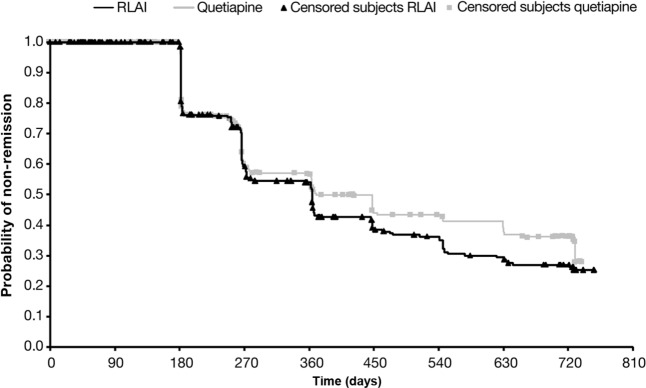

PANSS remission severity criteria were met at baseline by 113 patients treated with RLAI (34.6%) and 112 with quetiapine (34.4%). Full remission (including both severity and duration criteria) was more likely to occur at some point during the study in patients treated with RLAI(n = 167, 51.1%) than quetiapine (n = 128, 39.3%; p = 0.003). The percentage of patients in full remission at each assessment, starting at 6 months, is shown in Figure 1. Among those patients achieving full remission, remission was maintained until the end of the trial in 144 patients treated with RLAI (86.2%) and 102 treated with quetiapine (79.7%). This numerical difference was not significant. A Kaplan–Meier plot showing time to full remission for each treatment, using the combined severity and duration remission criteria, is shown in Figure 2. The HR using quetiapine treatment as the reference showed that the likelihood of reaching remission was numerically slightly higher with RLAI (1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.94–1.49). The Kaplan–Meier estimate of mean ± SE time to full remission was 422.6 ± 14.3 days with RLAI and 457.5 ± 16.5 days with quetiapine. Mean ± SD duration of full remission was 540.8 ± 181.4 days with RLAI and 508.1 ± 188.0 days with quetiapine. This numerical difference was not significant.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients in full remission by treatment month, starting at month 6.

RLAI, risperidone long-acting injectable.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to full remission. Log-rank test: p = 0.143.

RLAI, risperidone long-acting injectable.

Time to full remission was also evaluated in patients who completed the full 24 months of the study (n = 151 RLAI and n = 120 quetiapine). Among these patients, remission severity criteria were met at baseline by 55/151 patients treated with RLAI for 2 years and 34/120 patients with quetiapine for 2 years (36.4% versus 28.3%, p = 0.1929). Full remission criteria were met during the trial for 114/151 patients treated with RLAI for 2 years and 79/120 patients with quetiapine for 2 years (75.5% versus 65.8%, p = 0.1048). At endpoint, 101/151 patients receiving RLAI for 2 years (66.9%) and 72/120 patients receiving quetiapine for 2 years (60.0%) were in remission. Among this sample, the relative risk for reaching remission was similar between RLAI and quetiapine (HR 1.312, 95% CI 0.984–1.750).

Secondary efficacy outcomes

Endpoint changes in MADRS total and individual symptom scores and CGI-C are shown in Table 1. Improvements in each measure favoured RLAI, except for MADRS-reported sadness. According to CGI-C, at endpoint 86 RLAI patients (26.4%) and 64 quetiapine patients (19.7%) were improved, with 37 RLAI (11.3%) and 22 quetiapine (6.8%) patients ‘much’ or ‘very much’ improved.

Table 1.

Endpoint changes in secondary efficacy measures.

| Efficacy measure | RLAI (n = 326) |

Quetiapine | p-value (RLAI versus quetiapine) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS scores | |||

| Total | −2.85±8.65*** | −0.88±9.22* | 0.004 |

| Apparent sadness | −0.51±1.31*** | −0.22±1.29* | 0.003 |

| Reported sadness | −0.37±1.36*** | −0.23±1.32** | 0.177 |

| CGI-C | 0.03±1.23*** | −0.39±1.31# | <0.0001 |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation.

Decreases represent symptomatic improvement in MADRS scores.

CGI-C scores range from 3 (very much improved) to −3 (very much worse); improvement in CGI-C, therefore, is signified by a positive change.

Within-treatment change from baseline to endpoint was significant: #p < 0.05; *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001.

CGI-C, Clinical Global Impression–Change; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; RLAI, risperidone long-acting injectable.

Safety and tolerability

Safety data were available for all patients (329 RLAI and 337 quetiapine). TEAEs occurred similarly between treatment groups, most commonly psychiatric symptoms (43.2% of patients with RLAI and 43.0% with quetiapine) and nervous system disorders (18.8% with RLAI and 27.6% with quetiapine). Somnolence occurred in 11.3% of patients with quetiapine and 1.8% with RLAI. Death occurred in three patients treated with RLAI (two patients committed suicide and one had deep-vein thrombosis and peptic ulcer perforation) and two patients with quetiapine (one suicide and one myocardial infarction). None of the deaths was considered to be possibly or probably related to study drug by the principal investigator.

Discussion

Patients with clinically stable schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who switched to RLAI had a greater occurrence of sustained remission than those who switched to quetiapine. Remission was achieved by 51% of patients treated with RLAI compared with 39% receiving quetiapine (p = 0.003). Numerical differences favoured RLAI for maintaining full remission for the duration of the study and duration of remission, although these differences did not achieve statistical significance. Both remission and other secondary efficacy measures generally favoured RLAI.

Data from the current study parallel and confirm results reported by previously published open-label studies, switching symptomatically stable patients with schizophrenia and related disorders from stable antipsychotics to RLAI [Kissling et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2005]. Similar to these earlier open-label trials, the current study also found that remission severity criteria were met at baseline in around one-third of patients enrolled [Kissling et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2005]. A 50-week, open-label study has reported endpoint remission in 41% of patients switched to RLAI (21% of those not in remission at baseline and 85% of those in remission at baseline) [Lasser et al. 2005]. A 6-month extension to an initial 6-month, single-arm RLAI-switch study similarly reported remission in 45% of patients at endpoint (31% of those who were not in remission at baseline and 79% of those who were) [Kissling et al. 2005].

Interpretation of these data is limited by factors inherent to all open-label treatment studies. An important question is whether differential outcomes between injectable and oral drugs reflect differences in delivery systems, rather than the drugs themselves. Previous research has shown comparable efficacy for patients with stable schizophrenia treated with RLAI versus oral risperidone [Bai et al. 2006], and better efficacy with oral risperidone compared with quetiapine [Komossa et al. 2010]. These results are supported by a meta-analysis by Davis and colleagues, demonstrating significant differences between individual second-generation antipsychotics with better efficacy for oral risperidone over first-generation antipsychotics, compared with quetiapine [Davis et al. 2003]. Previous publications have additionally reported reduced relapse with RLAI compared with oral antipsychotics; however, treatment adherence is generally better with RLAI, which likely confers an impact to better efficacy maintenance [Emsley et al. 2008b; Kim et al. 2008; Olivares et al. 2009]. Comparisons of remission data among long-term users of RLAI and quetiapine (24-month completers) may be limited due to the higher dropout rate among patients treated with quetiapine. In addition, quetiapine doses used in clinical practice may be higher than those used in the current study. However, mean doses of both drugs were similar to effective doses reported in other controlled clinical trials for schizophrenia or related disorders; RLAI near-maximal effective dose 25 mg every 2 weeks and quetiapine near-maximal effective dose 150–600 mg/day [Davis and Chen, 2004]. In addition, face-to-face contact time was greater for patients treated with RLAI due to appointments required for injection administration, compared with quetiapine patients whose 2-weekly follow-up appointments were conducted by telephone. The therapeutic benefit with RLAI may have been accentuated by more frequent face-to-face contact.

Furthermore, analysing patients with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as a single group may have affected the results. In comparison with patients with schizophrenia, patients diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder typically function better prior to the onset of psychotic symptoms, have psychotic symptoms that are often relatively briefer in duration (although usually recurrent), and have a more favourable long-term prognosis than patients with schizophrenia [Marneros, 2003]. It has been argued that evaluations of patients with psychotic disorders should ideally include separate evaluations for those with schizophrenia and those with schizoaffective disorder, due to differences in disease characteristics and anticipated outcome [Huber et al. 2008]. Moreover, a recent review of clinical trials evaluating treatment of schizoaffective disorder was unable to reach a conclusion about whether antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or a combination of these therapies should be the preferred treatment in this patient group [Jäger et al. 2010]. An independent analysis of patients with schizoaffective disorder might add to the understanding of benefits with antipsychotic therapy when used in patients who were or were not concomitantly using mood stabilizers. Furthermore, over half of all patients withdrew before completing the full 2-year treatment; with treatment completed by 46% with RLAI and 36% with quetiapine. Rates and reasons for withdrawal were comparable with an earlier, analogous study of stable patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder randomized to oral risperidone or haloperidol [Csernansky et al. 2002]. In this study, 18% of patients given either risperidone or haloperidol withdrew due to patient choice, 12% of risperidone and 15% of haloperidol patients withdrew due to side effects, and 14% of risperidone and 20% of haloperidol patients withdrew for reasons other than relapse. Likewise, only 12 of the initial 29 patients in a trial randomizing patients to quetiapine or haloperidol decanoate for 48 weeks completed treatment [Glick and Marder, 2005].

Furthermore, in the current study, as patients were clinically stable but requiring/desiring a treatment change at study entry, additional analysis on extent of improvement would supplement data on evaluation of symptom worsening or relapse after switching therapies. Finally, efficacy may have been overestimated by having to exclude patients who had been previously determined to be risperidone or quetiapine nonresponders because they were unlikely to benefit from the treatment provided during the study, therefore, including an artificially high proportion of potential responders. Future analyses may include an evaluation of factors that may have predicted remission in each patient group, including treatment noncompliance, baseline remission and baseline symptom severity.

In summary, data from the current study demonstrate good sustained remission in patients with stable schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched to RLAI treatment. Remission occurred more frequently among patients treated with RLAI compared with the oral atypical quetiapine (51% versus 39%, p = 0.003). Duration of remission was not significantly different between treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Rossella Medori for trial design and medical-conduct supervision. Dr Medori was European Medical Director at Janssen-Cilag during study conduct and analysis. Dr Alice Lex from Janssen-Cilag GmbH was involved in protocol design, protocol execution, and reporting. Paul Bergmans from Janssen-Cilag BV, the Netherlands, is also acknowledged for providing statistical analyses. Editorial and writing support was provided by Tam Vo, PhD, and a team from Excerpta Medica.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported with a grant provided by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson in EMEA.

Declaration of conflicting interests: Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson in EMEA designed the study and collected and analysed the data. Non-Janssen-Cilag- affiliated (independent) authors were fully responsible for interpreting the data and had access to the data. All authors were involved in the writing of the report and were responsible for the decision to submit the paper for publication. Enrico Smeraldi received research grants and fees for consultancy from Janssen. Roberto Cavallaro received fees for consultancy, participation to advisory boards from Janssen, and as a speaker from Janssen, and Pfizer.

Vera Folnegović-Šmalc declares no conflicts of interest. Leszek Bidzan has received research grants from Eli Lilly and has given industry-sponsored lectures for Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Novartis, Pfizer, KRKA and Sanofi. Mehmet Emin Ceylan received consultancy fees from Janssen-Cilag. Andreas Schreiner is an employee and a member of Medical Affairs EMEA at Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Germany, and is a shareholder of Johnson & Johnson.

Contributor Information

Enrico Smeraldi, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, San Raffaele University Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute University School of Medicine, Via Stamira D’Ancona 20, 20127 Milan, Italy.

Roberto Cavallaro, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, I.R.C.C.S. Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy.

Vera Folnegović-Šmalc, University Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Hospital Vrapče, Zagreb, Croatia.

Leszek Bidzan, Department of Developmental, Psychotic, and Geriatric Psychiatry, Medical University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland.

Mehmet Emin Ceylan, Molecular Biology and Genetics Department, Uskudar University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Andreas Schreiner, Medical Affairs EMEA, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Neuss, Germany.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N., Carpenter W., Jr, Kane J., Lasser R., Marder S., Weinberger D. (2005) Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 162: 441–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Chen T., Wu B., Hung C., Lin W., Hu T., et al. (2006) A comparative efficacy and safety study of long-acting risperidone injection and risperidone oral tablets among hospitalized patients: 12-week randomized, single-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry 39: 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad A., Álvarez E., Bobes J., San L., Polavieja P., Gilaberte I. (2009) Remission in schizophrenia: results from a 1-year follow-up observational study. Schizophr Res 108: 214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csernansky J., Mahmoud R., Brenner R., Risperidone-USA-79 Study Group (2002) A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 346: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L., Schmutte T., Dinzeo T., Andres-Hyman R. (2008) Remission and recovery in schizophrenia: practitioner and patient perspectives. Schizophr Bull 34: 5–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Chen N. (2004) Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 24: 192–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Chen N., Glick I. (2003) A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 553–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arce Cordón R., Eding E., Marques-Teixeira J., Milanova V., Rancans E., Schreiner A. (2012) Descriptive analyses of the aripiprazole arm in the risperidone long-acting injectable versus quetiapine relapse prevention trial (ConstaTRE). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262: 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz I., Pelayo-Terán J., Pérez-Iglesias R., Mata I., Tabarés-Seisdedos R., Suárez-Pinilla P., et al. (2012) Predictors of clinical remission following a first episode of non-affective psychosis: Sociodemographics, premorbid and clinical variables. Psychiatry Res pii: S0165–1781(12)00641–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolder C., Lacro J., Dunn L., Jeste D. (2002) Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? Am J Psychiatry 159: 103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevich E., Sethuraman G., Enerson M., Taylor C., Lin D. (2006) Characteristics of two alternative schizophrenia remission definitions: relationship to clinical and quality of life outcomes. Schizophr Res 86: 300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R., Medori R., Koen L., Oosthuizen P., Niehaus D., Rabinowitz J. (2008a) Long-acting injectable risperidone in the treatment of subjects with recent-onset psychosis: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28: 210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R., Oosthuizen P., Koen L., Niehaus D., Medori R., Rabinowitz J. (2008b) Oral versus injectable antipsychotic treatment in early psychosis: post hoc comparison of two studies. Clin Ther 30: 2378–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W., Schreiner A., Bergmans P., de Arce R., Rouillon F., Cordes J., et al. (2010) Relapse prevention in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder with risperidone long-acting injectable versus quetiapine: results of a long-term, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 2367–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick I., Marder S. (2005) Long-term maintenance therapy with quetiapine versus haloperidol decanoate in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 638–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes V., Zhu B., Stauffer V., Kinon B., Stensland M., Xu L., et al. (2012) Long-term healthcare costs and functional outcomes associated with lack of remission in schizophrenia: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatr 12: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C., Naber D., Lambert M. (2008) Incomplete remission and treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: definition, prevalence and predictors. Expert Opin Pharmacother 9: 2027–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger M., Becker T., Weinmann S., Frasch K. (2010) Treatment of schizoaffective disorder - a challenge for evidence-based psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand 121: 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. (2006) Review of treatments that can ameliorate nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 67(Suppl. 5): 9–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. (2007) Treatment adherence and long-term outcomes. CNS Spectr 12(Suppl. 17): 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Lee S., Choi T., Suh S., Kim Y., Lee E., et al. (2008) Efficacy of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32: 1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissling W., Heres S., Lloyd K., Sacchetti E., Bouhours P., Medori R., et al. (2005) Direct transition to long-acting risperidone–analysis of long-term efficacy. J Psychopharmacol 19(Suppl.): 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., Schmid F., Hunger H., Schwarz S., Srisurapanont M., et al. (2010) Quetiapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD006625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M., Karow A., Leucht S., Schimmelmann B., Naber D. (2010) Remission in schizophrenia: validity, frequency, predictors, and patients’ perspective 5 years later. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 12: 393–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser R., Bossie C., Gharabawi G., Kane J. (2005) Remission in schizophrenia: Results from a 1-year study of long-acting risperidone injection. Schizophr Res 77: 215–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Heres S. (2006) Epidemiology, clinical consequences, and psychosocial treatment of nonadherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 67(Suppl. 5): 3–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M., Godemann F. (2007) The differentiation between “lack of insight” and “dysfunctional health beliefs” in schizophrenia. Psychopathology 40: 236–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca P., Sacchetti E., Lloyd K., Kissling W., Medori R. (2008) Long-term remission in schizophrenia and related psychoses with long-acting risperidone: results obtained in an open-label study with an observation period of 18 months. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 46: 14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löffler W., Kilian R., Toumi M., Angermeyer M. (2003) Schizophrenic patients’ subjective reasons for compliance and noncompliance with neuroleptic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry 36: 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marneros A. (2003) Schizoaffective disorder: clinical aspects, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 5: 202–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares J., Peuskens J., Pecenak J., Resseler S., Jacobs A., Akhras K., et al. (2009) Clinical and resource-use outcomes of risperidone longacting injection in recent and long-term diagnosed schizophrenia patients: results from a multinational electronic registry. Curr Med Res Opin 25: 2197–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa M., Marcolin M., Elkis H. (2005) Evaluation of the factors interfering with drug treatment compliance among Brazilian patients with schizophrenia. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 27: 178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San L., Ciudad A., Alvarez E., Bobes J., Gilaberte I. (2007) Symptomatic remission and social/vocational functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia: prevalence and associations in a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry 22: 490–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler N. (2003) Relapse and rehospitalization: comparing oral and depot antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 64(Suppl. 16): 14–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler N. (2006) Relapse prevention and recovery in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 67(Suppl. 5): 19–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderink L., Niehuis F., Sytem S., Wiersma D. (2007) Predictive validity of proposed remission criteria in first-episode schizophrenic patients responding to antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull 33: 792–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Watanabe K., Nemoto N., Fujita H., Chikaraishi C., Yamauchi K., et al. (2006) Prediction of medication noncompliance in outpatients with schizophrenia: 2-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res 141: 61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhornitsky S., Stip E. (2012) Oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and special populations at risk for treatment nonadherence: a systematic review. Schizophr Res Treatment 2012: 407171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]