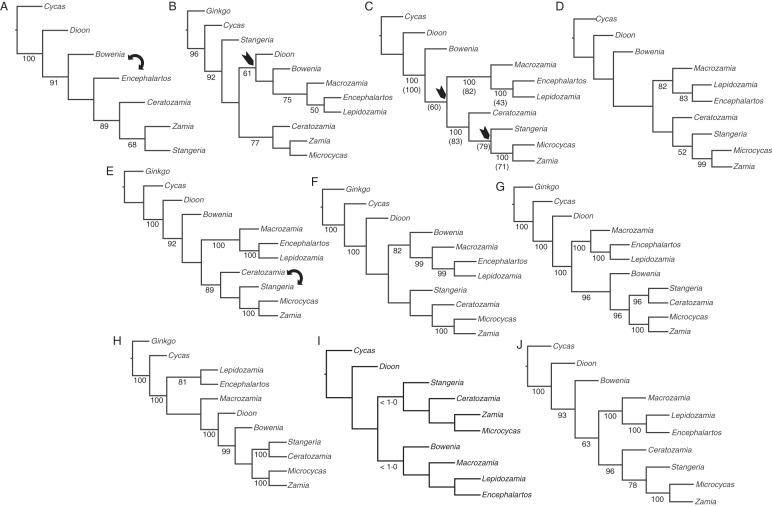

Fig. 2.

Molecular phylogenetic trees of Cycadales from various authors. Numbers below branches are bootstrap percentages ≥50 unless otherwise stated. (A) One of the two most-parsimonious trees from analysis of 17 plastid genes and non-coding regions (Rai et al., 2003). The second tree exchanged positions for Bowenia and Encephalartos (double-headed arrow). (B) One of the 81 most-parsimonious trees from analysis of concatenated plastid rbcL and trnL-F, and nrDNA ITS and 26S (Hill et al., 2003). (C) One of the 45 most-parsimonious trees from analysis of plastid matK (Chaw et al., 2005). Arrows indicate nodes that collapse in the strict consensus. With nrDNA ITS, the authors found the four most-parsimonious trees, the strict consensus of which was fully resolved at the generic level. Bootstrap values in parentheses are from the ITS analysis. (D) Single most-parsimonious tree found by Bogler and Francisco-Ortega (2004) using combined plastid trnL-F and nrDNA ITS2. (E) One of the two most-parsimonious trees found in the analysis of Zgurski et al. (2008) of the same 17 plastid genes and non-coding regions used by Rai et al. (2003). (F–H) Maximum likelihood trees from Nagalingum et al. (2011). (F) Plastid rbcL and matK. (G) Nuclear PHYP. (H) Combined plastid and nuclear genes. (I) Cladogram of Cycadales inferred from the maximum clade credability chronogram of the gymnosperms using plastid matK and 25S nrDNA (Crisp and Cook, 2011). Numbers below branches indicate those branches with posterior probabilities <1·0. (J) Strict consensus of the 96 most-parsimonious trees based on analysis of combined plastid matK, rpoB and rps4, mitochondrial mtITS and nad1, nrITS, nuclear NEEDLY sequences and 130 morphological characters (Griffith et al., 2012).