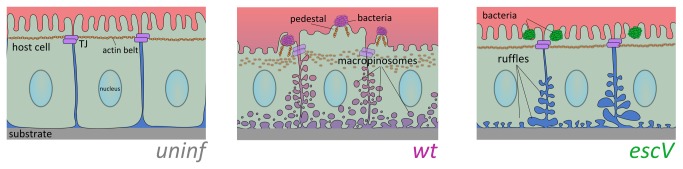

Figure 5. Schematic representation of the effects of EPEC infection on epithelial host cell architecture.

In normal uninfected columnar epithelial cells (left panel), the cells maintain close intercellular contacts via tight junctions (TJ), and other junctional complexes (e.g., adherence junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes). These junction complexes allow the regulation and exchange of different compounds between the underlying tissues and external body cavities, as well as among the connected cells. They are also responsible for maintaining physical contact between the cells and the underlying substrate. In particular, epithelial TJs, which are linked to actin fibers (the apical actin belt), interconnect individual cells into a continuous and rigid epithelial cell sheet. Proper TJ-actin interconnections are essential for developing tall and columnar epithelial cell morphology [42,43]. EPEC-wt (middle panel) attached to the apical cell surface of host epithelial cells injects a series of protein effectors into the host cells via T3SS (not shown), among which are effector proteins that subvert the TJs and the actin cytoskeleton, and thereby have broad effects on the epithelial host cell monolayer. Our novel findings suggest that some effector proteins exclusively induce the formation of large fluid-phase-filled endocytic vesicles, reminiscent of (macro)pinosomes. They also evoke substantial host cell detachment from the underlying substratum and a reduction in cell height. The latter could be contributed by a loss of the cortical actin tension maintained by the TJs and the associated cortical actin belt [43]. On the basis of these observations, and combined with other data implying that EPEC disrupts the TJ barrier functions, we can conclude that apically adhered EPEC impair the structural properties of the host in a way that causes a watery extracellular environment to infiltrate into the epithelial sheets, and possibly to the gut’s lumen, which contributes to the diarrheal effect. EPEC-escV (right panel) causes host cell basolateral membrane ruffling, expansion of intercellular spaces and some degree of host cell detachment, but does not initiate (macro)pinocytic vesicles formation. EPEC-escV has a much weaker effect on the disorganization of the epithelial cell monolayer and the actin cytoskeleton, which still allows the maintenance of the epithelium barrier function. Clearly, these type III secretion independent processes might be contributed by factors associated with the bacterial exterior. One interesting candidate is the EPEC bundle-forming pilus (BFP), which extends out from the bacteria and mediates the initial attachment of EPEC to its host [4]. Following attachment to the host, BFP retracts by a very powerful force generating machinery, bringing to a close apposition the bacterial and host cell surfaces [53]. The host cell may respond to this mechanical force by reorganizing its cortical actin cytoskeleton [54,55], signal transducing proteins [56] and proteins of the junction polarity complex [57]. An intriguing hypothesis is that at least some of these effects have contributed to the type III-independent changes observed upon EPEC-escV attachment to its host.