Abstract

Antidiscrimination law offers protection to workers who have been treated unfairly on the basis of their race, gender, religion, or national origin. In order for these protections to be invoked, however, potential plaintiffs must be aware of and able to document discriminatory treatment. Given the subtlety of contemporary forms of discrimination, it is often difficult to identify discrimination when it has taken place. The methodology of field experiments offers one approach to measuring and detecting hiring discrimination, providing direct observation of discrimination in real-world settings. In this article, we discuss the findings of two recent field experiments measuring racial discrimination in low wage labor markets. This research provides several relevant findings for researchers and those interested in civil rights enforcement: (1) it produces estimates of the rate of discrimination at the point of hire; (2) it yields evidence about the interactions associated with discrimination (many of which reveal the subtlety with which contemporary discrimination is practiced); and (3) it provides a vehicle for both research on and enforcement of antidiscrimination law.

Antidiscrimination law offers protection to workers who have been treated unfairly on the basis of their race, gender, religion, or national origin. In order for these protections to be invoked, however, potential plaintiffs must be aware of and able to document discriminatory treatment. In the case of unequal pay or wrongful termination, employees are often able to gather sufficient evidence based on information about coworkers or through interactions with the employer to identify and document unfair treatment. In the case of hiring discrimination, by contrast, applicants have very little information with which to assess the legitimacy of employers’ decision-making. With little or no information about the qualifications of other applicants, the relevant needs of the employer or requirements of the job, applicants who may have been unfairly dismissed on the basis of their race or gender are often left unaware or unable to take action (see also Bendick & Nunes, 2012).

Indeed, trends in the composition of antidiscrimination enforcement show that, in stark contrast to the composition of claims filed in the 1970s, claims today are far more likely to emphasize wrongful termination or on-the-job discrimination than to target instances of discrimination at the point of hire. In the mid-1960s charges of discrimination in hiring outnumbered charges of wrongful termination by 50%; by the mid-1980s this ratio had reversed by more than 6 to 1 (Donohue & Siegelman, 1991, p. 1015). This changing pattern of claims could reflect a change in the distribution of discrimination, indicating a reduction in discrimination at the point of hire relative to increases (relative or absolute) in wage discrimination or wrongful termination. The bulk of evidence, by contrast, suggests that declines in claims of hiring discrimination result from changing standards of legal evidence and the difficulties facing plaintiffs in acquiring the necessary information to pursue a successful claim (Nielsen & Nelson, 2005). In fact, changing patterns of enforcement may have the perverse effect of increasing the relative importance of discrimination at the point of hire. Declining enforcement of discrimination at the point of hire lowers the risk to employers who discriminate at this stage; the simultaneous increase in the rate of claims for wrongful termination increases the risks associated with firing minority workers (see Donohue & Siegelman, 1991, p. 1024; Posner, 1987, p. 519). Thus, despite the fact that claims of employment discrimination at any stage are rare, their relative distribution implies far less vulnerability for employers over decisions made at the initial-hiring stage. It may be the case, then, that even if overall levels of racial discrimination have declined, the relative importance of hiring discrimination (compared to discrimination at later stages) may be increasing in importance.

Like applicants, researchers face similar difficulties in identifying discrimination in labor markets. Social psychological studies demonstrate the persistence of stereotypes and biases and their effects on conscious and unconscious decision-making, but lab-based studies often have limited generalizability to real-world outcomes (Levitt & List, 2007) Survey-based analyses more typical of research in sociology and economics can identify race or gender gaps in employment or wages, but residual estimates from statistical models leave open the possibility of omitted variables that may inflate estimates of discrimination (see, for example, the debate between Cancio et al., 1996 and Farkas & Vicknair, 1996).

Direct measures of hiring discrimination are few and far between. Particularly in the contemporary United States where acts of discrimination are likely to be subtle and covert, it is extremely difficult to measure discrimination directly. Fortunately, the methodology of field experiments offers one approach to the study of hiring discrimination which allows researchers to directly observe discrimination in real-world settings. In this article, we discuss the findings of two recent field experiments measuring racial discrimination in low wage labor markets. Complementing Bendick and Egan (2012)—which offers a review of the broader potential of field experiments—this article focuses on the use of field experiments to reveal both gross-hiring inequities and extremely subtle processes of bias in decision-making. Providing both quantitative evidence of hiring discrimination and qualitative evidence of bias in the hiring process, field experiments represent a powerful tool for researchers and those interested in civil rights enforcement. In the following discussion, we illustrate three desirable features of the field experiment: (1) it produces estimates of the rate of discrimination at the point of hire; (2) it yields evidence about the interactions associated with discrimination (many of which reveal the subtlety with which contemporary discrimination is practiced); and (3) it provides a vehicle for both research on and enforcement of antidiscrimination law.

Field Experiments for Measuring Discrimination

The basic design of an employment audit involves sending matched pairs of individuals (called testers) to apply for real job openings in order to see whether employers respond differently to applicants on the basis of selected characteristics. The appeal of the audit methodology lies in its ability to combine experimental methods with real-life contexts. This combination allows for greater generalizability than a lab experiment, and a better grasp of the causal mechanisms than what we can normally obtain from observational or correlational data. Indeed, for those with an interest in studying discrimination in real-world settings, the audit methodology provides an ideal tool.

The audit approach has been applied to numerous settings, including mortgage applications, negotiations at a car dealership, housing searches, and hailing a taxi (Ayres & Siegelman, 1995; Bendick et al., 1994; Cross et al., 1990; Massey & Lundy, 2001; Neumark, 1996; Ridley et al., 1989; Turner et al., 1991; Turner & Skidmore, 1999; Yinger, 1995). In the employment context, researchers have studied hiring discrimination by presenting employers with equivalent applicants who differ only by their race or ethnicity, either via resumes (known as “correspondence studies”) or through in-person applicants (“in-person audit studies”). Marian Betrand and Sendhill Mullainathan (2004), for example, prepared two sets of matched resumes reflecting applicant pools of two skill levels. Using racially distinctive names to signal the race of applicants, the researchers mailed out resumes to more than 1,300 employers in Chicago and Boston, targeting job ads for sales, administrative support, and clerical and customer-services positions. The results of their study indicate that White-sounding names were 50% more likely to elicit positive responses from employers relative to equally qualified applicants with “Black” names (9.7% vs. 6.5%). Moreover, applicants with White names received a significant payoff to additional qualifications, while those with Black names did not. The racial gap among job applicants was thus higher among the more highly skilled applicant pairs than among those with fewer qualifications.

The primary advantage of the correspondence-test approach is that it requires no actual job applicants (only fictitious paper applicants). This is desirable for both methodological and practical reasons. Methodologically, the use of fictitious paper applicants allows researchers to create carefully matched applicant pairs without needing to accommodate the complexities of real people. The researcher thus has far more control over the precise content of “treatment” and “control” conditions. Practically, the reliance on paper applicants is also desirable in terms of the logistical ease with which the application process can be carried out. Rather than coordinating job visits by real people (creating opportunities for applicants to get lost, to contact the employer under differing circumstances), the correspondence test approach simply requires that resumes be sent out at specified intervals. Additionally, the small cost of postage or fax charges is trivial relative to the cost involved in hiring individuals to pose as job applicants.

At the same time, while correspondence tests do have many attractive features, there are also certain limitations of this design that have led some researchers to prefer the in-person audit approach. First, because correspondence tests rely on paper applications only, all relevant target information must be conveyed without the visual cues of in-person contact. This can pose complications for certain signals. The correspondence study discussed above, for example, used names like “Jamal” and “Lakisha” to signal African Americans. While these names are reliably associated with their intended race groups, some critics have argued that the more distinctive African American names are also associated with lower socioeconomic status, thus confounding the effects of race and class. Indeed, mother's education is a significant (negative) predictor of a child having a distinctively African American name (Fryer & Levitt, 2004). Directly assessing these connotations/associations is thus an important first step in developing the materials necessary for a strong test of discrimination.

In addition to signaling complexities, the correspondence-test method is also somewhat limited with respect to the types of jobs available for testing. The type of application procedure used in correspondence tests—sending resumes by mail—is typically reserved for studies of administrative, clerical, and other white-collar occupations. The vast majority of entry-level jobs, by contrast, often require inperson applications. For jobs such as busboy, messenger, laborer, or cashier, for example, a mailed-in resume would appear out of place.

Finally, as we discuss below, correspondence studies are limited in the information they provide about the evaluation process that precedes the hiring decision. The ability to observe the level of attention, encouragement, or hostility applicants elicit can provide important information about the subtle and contingent aspects of hiring process. For many of these reasons, some researchers have turned to the use of in-person audit studies.

Though in-person audits are time consuming and require intensive supervision, the approach offers several desirable qualities. In-person audits allow for the inclusion of a wide range of entry-level job types (which often require in-person applications); they provide a clear method for signaling race, without concerns over the class connotations of racially distinctive names (e.g., Fryer & Levitt, 2004); and they provide the opportunity to gather both quantitative and qualitative data, with information on whether or not the applicant receives the job as well as how he or she is treated during the interview process. Unfortunately, in part because of taxing logistical requirements, the use of in-person audit studies of employment remains quite rare, with only a handful of such studies conducted over the past 20 years (Bendick et al., 1991; Bendick et al. 1994; Cross et al. 1990; Pager, 2003; Turner et al. 1991; for a recent summary, see Pager 2007a).

The current article discusses the results from two recent field experiments that used an in-person audit approach to study racial and ethnic discrimination in the low wage labor markets of Milwaukee and New York City. In both studies, young men between the ages of 21 and 24 were hired to play the role of job applicants. These young men (called testers) were matched on the basis of their physical appearance (height, weight, attractiveness), verbal skills, and interactional styles (level of eye-contact, demeanor, and verbosity). Testers were assigned fictitious resumes indicating identical educational attainment, work experience (quantity and kind), and neighborhood of residence. Resumes were prepared in different fonts and formats and randomly varied across testers, with each resume used by testers from each race group. Testers presented themselves as high school graduates with steady work experience in entry-level jobs. Finally, the testers passed through a common training program to ensure uniform behavior in job interviews. While in the field, the testers dressed similarly and communicated with teammates by cell phone to anticipate unusual interview situations. In Milwaukee, racial comparisons are based on between-team comparisons, as Black and White testers applied to separate employers (the effect of a criminal record was measured within same-race pairs (see Pager, 2003). In New York City, Black, White, and Latino testers applied to the same set of employers for racial comparisons based within team.

Entry level job listings, defined as jobs requiring no previous experience and no education greater than high school, were randomly selected each week from the classified sections of the major city newspapers. Job titles included restaurant jobs, retail sales, warehouse workers, couriers, telemarketers, customer-service positions, clerical workers, stockers, movers, delivery drivers, and a wide range of other low-wage positions. Jobs were randomly assigned across teams, with testers in each team randomly varying the order in which they applied for each position. Eight testers in the Milwaukee study visited 350 employers; 10 testers in the New York City study visited 340 employers. The dependent variable in each study recorded any positive response in which a tester was either offered a job or called back for a second interview. Callbacks were recorded by voicemail boxes set up for each tester.

Results

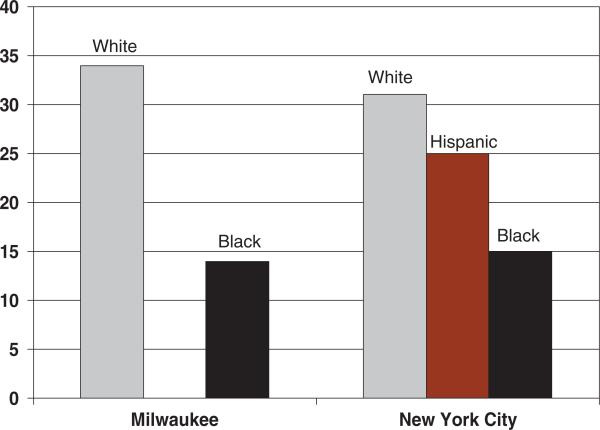

Figure 1 presents the percent of applicants receiving a callback or job offer, by race of the applicant. The results across the two cities are highly consistent, with Whites receiving positive responses at roughly twice the rate of equally qualified Black applicants. In the Milwaukee study, Whites received callbacks or job offers in 34% of cases relative to 14% for equally qualified Black applicants (p < .01). In New York City, Whites received callbacks or job offers in 31% of cases, relative to 25% of Latino applicants and 15% for Blacks (for Black–White comparison, p < .01). The remarkable consistency of Black–White disparities across the two cities suggests that racial discrimination in hiring is not the product of distinctive local cultures or labor market dynamics but rather a more generalized phenomenon. Milwaukee and New York are quite distinct in their demographics, industrial composition, segregation patterns, and histories of racial conflict. Despite these differences, the prevalence and magnitude of discrimination in both cities is nearly identical.

Fig. 1.

Percent of applicants receiving a callback or job offer, by race.

Perceptibility of Discrimination

Despite the frequency of differential treatment recorded in these data, few of the incidents were noticeable from the job applicant's perspective. In the Milwaukee experiment, more than three fourths of applications were submitted with little or no personal contact with the employer. In such cases, applicants have virtually no information with which to assess their reception by employers, and employers make first-round cuts on the basis of superficial impressions (if they see the applicant), a name on the resume, or the brief information provided on the application form. Testers in Milwaukee generally reported cordial treatment by employers and, apart from a few notable exceptions, Black testers did not feel unwelcome submitting their applications.

In the New York City experiment, testers more often had the opportunity to talk with employers, with such conversations occurring in roughly half of the firms to which they applied. But even in these cases it was difficult to decipher the employer's preferences or biases based on a single interaction. Indeed, in many cases it was only after the side by side comparisons of test partners that evidence of possible bias could be detected. In one case from the New York City study, for example, the three testers inquired about a sales position at a retail clothing store. The employer spoke with each of the applicants and appeared to treat each one fairly.

Joe, one of our African-American tester, reported: “[The employer] said the position was just filled and that she would be calling people in for an interview if the person doesn't work out.” Josue, his Latino-test partner, was told something very similar: “She informed me that the position was already filled, but did not know if the hired employee would work out. She told me to leave my resume with her.” By contrast, when Simon, their White-test partner, applied last, his experience was notably different: “ . . . I asked what the hiring process was—if they're taking applications now, interviewing, etc. She looked at my application. ‘You can start immediately?’ Yes. ‘Can you start tomorrow?’ Yes. ‘10 a.m.’ She was very friendly and introduced me to another woman (White, 28) at the cash register who will be training me.”

When evaluated individually, these interactions would not have raised any concern. All three testers were asked about their availability and about their sales experience. The employer appeared willing to consider each of them. But when it came down to it, it was the White applicant who walked out with the job.

Indeed, in the majority of applications testers did not detect signs from employers that anticipated the differential treatment we observed. As a way of gauging testers’ subjective experiences, we had testers in the New York City study fill out “treatment thermometers” recording their perception of how they were treated by an employer after each visit. On a scale of 1 to 100, the average rating for Blacks was 69.6 overall, and among Blacks experiencing differential treatment, 67.5. This small and statistically insignificant decrease in perceived treatment suggests that employers’ preferences and biases were largely concealed in the interview process, with the majority of Black applicants unaware that their candidacy was in question.

Some have argued that Blacks are quick to interpret ambiguous interactions as evidence of racism (Ford, 2008), a concern particularly relevant to a study that relies on the performance of testers who are aware of the intended focus of the research (Heckman, 1998). Quite unlike expectations that testers would be vigilant in perceiving the slightest hint of foul play, the present research suggests that testers were rarely able to identify discrimination at work. Indeed, this research is more consistent with social psychological studies that suggest targets of discrimination often underestimate the significance of discrimination in their own lives, even as they recognize it as a problem facing their group (Crosby, 1984; Taylor et al., 1990).

In addition to testers’ weak ability to perceive discrimination in action, testers’ perceptions of their treatment by employers did little to predict their actual likelihood of employment. There was essentially zero correlation between testers’ ratings on the “treatment thermometer” and their likelihood of getting a callback. Excluding those cases in which testers were offered the job on the spot (and therefore, the tester had concrete feedback regarding the employers’ approval), the correlation between the “treatment thermometer” score and the likelihood of a callback was .02 for Whites and .05 for Blacks. The friendliness or gruffness of an employer thus did little to signal actual-hiring intentions. Even among these “professional applicants”—in the sense that our testers were being paid to monitor the application process and had significant experience with a wide range of employment interactions—their ability to detect racial preferences at work was extremely limited.

In most cases, it is only by comparing the experiences of similar applicants side by side that we observe the ways in which race appears to shape employers’ evaluations in subtle but systematic ways. These patterns have significant implications for the enforcement of antidiscrimination law. The reliance on individual plaintiffs to come forward with evidence of discrimination represents a bar that few incidents of hiring discrimination can meet. In contrast to cases of wage discrimination or wrongful termination, in which victims presumably have access to better information about the comparative treatment of other similarly situated employees, job applicants have access to very little information with which to gauge suspicions of discrimination. Moreover, because acts of discrimination are themselves typically subtle and covert, the applicant's suspicions are unlikely to be aroused even when systematic or regularly occurring forms of bias are solidly in place. Under these conditions, we would expect the vast majority of incidents of hiring discrimination to go undetected. The difficulty in identifying and enforcing discrimination at the point of hire leaves this stage of the employment process particularly vulnerable to the influences of persistent racial bias.

Are Employers Hiding Racist Beliefs?

Employers are adamant that race does not affect their decisions about who to hire; they speak about looking for the best-possible candidate whether “White, Black, Yellow or Green” (employer at a retail clothing store). In order to better understand employers’ perspectives on hiring, we conducted in-depth interviews with 55 employers in New York City (Pager & Karafin, 2009). When asked what his sense was of how African American men are doing in terms of employment compared to other groups, the manager of a supply company simply said, “Skip that question because that has nothing to do with me. I just hire people based on their abilities.” Another employer for a retail sales company expressed a common sentiment of universality: “Number one, they are all the same to me. When I look, I don't look at religion, I don't look at what color you are because we are all human beings.” These employers, like many we spoke with, appear committed to an evaluation process that is blind to race or color.

At the same time, when asked to step back from their own hiring process to think about race differences more generally, employers were surprisingly willing to express strong opinions about the characteristics and attributes they perceive among different groups of workers. Indeed, the plurality of employers we spoke with, when considering Black men independent of their own workplace, characterized this group according to three common tropes: as lazy or having a poor work ethic; threatening or criminal; or possessing an inappropriate style or demeanor (Pager & Karafin, 2009). For example, one employer at a retail store said simply, “I will tell you the truth. African Americans don't want to work.” An employer at a local garment factory commented, “I find that the great majority of this minority group that you are talking about either doesn't qualify for certain jobs because they look a little bit more, they come on as if, well, they are threatening.” Previous studies have found similar characterizations by employers in the context of open-ended interviews (Kirschenman & Neckerman, 1991; Moss & Tilly, 2001; Waldinger & Lichter, 2003; Wilson, 1996).

One possible interpretation of this discrepancy, between employers’ characterization of their own color-blind hiring philosophy and their strong negative portrayals of Black men, is simply that employers work to conceal the ways that their own biases result in discriminatory hiring practices. Surely employers who hold such negative stereotypes about African Americans are unlikely to give them a fair shake in the hiring process. And yet, a puzzling finding in attempts to match employer attitudes with hiring behavior is the striking lack of consistency between the two (Moss & Tilly, 2001; Pager & Quillian, 2005; see also LaPiere, 1934). In some cases, employers expressing strong negative attitudes about Black men appear more likely to hire Black-male applicants. Indeed, Moss and Tilly (2001) report the surprising finding that “businesses where a plurality of managers complained about Black motivation [and other negative characteristics] are more likely to hire Black men” (p.151). These results point the fact that hiring decisions are influenced by a complex range of factors, conscious racial attitudes being only one. The stated preferences of employers, then, leave uncertain the degree to which negative attitudes about Blacks translate into active forms of discrimination.

Indeed, it is difficult to know exactly what is going through employers’ minds as they evaluate candidates of different races. Based on the evidence we can glean from the interactions between testers and employers in our field experiments, it seemed that only in rare cases were employers categorically unwilling to hire African Americans (see Pager et al., 2009, p. 787–788). Rather, employers often seemed genuinely interested in evaluating the qualifications of a given candidate, irrespective of their race in an effort to identify the best candidate for the job. Unfortunately, these evaluations themselves appeared influenced by race. Indeed, in analyzing the interactions between employers and our testers, we noticed a pattern in which employers appeared to perceive real-skill or experience differences among applicants despite the fact that the testers’ resumes were designed to convey identical qualifications (for additional discussion and analyses of these interactions see Pager, Western, and Bonikowski, 2009). In one case from NYC, for example, the testers applied for a job at a moving company.

Joe, the African American applicant, spoke with the employer about his prior experience at a delivery company. Nevertheless, “[the employer] told me that he couldn't use me because he is looking for someone with moving experience.” Josue, his Latino partner, presented his experience as a stocker at a delivery company and reports a similar reaction: “He then told me that since I have no experience . . . there is nothing he could do for me.” Simon, their White-test partner, presented his identical qualifications to which the employer responds more favorably: “‘To be honest, we're looking for someone with specific moving experience. But because you've worked for [a storage company], that has a little to do with moving.’ He wanted me to come in tomorrow between 10 and 11 for an interview.”

The employer is consistent in his preference for workers with relevant prior experience, but he is willing to apply a more flexible, inclusive standard in evaluating the experience of the White applicant than in the case of the minority applicants.

When applying for a job as a line cook at a midlevel Manhattan restaurant, the three testers encountered similar concerns about their lack of relevant experience.

Josue, the Latino tester, reported, “[The employer] then asked me if I had any prior kitchen or cooking experience. I told him that I did not really have any, but that I worked alongside cooks at [my prior job as a server]. He then asked me if I had any ‘knife’ experience and I told him no . . . He told me he would give me a try and wanted to know if I was available this coming Sunday at 2 p.m.” Simon, his White-test partner, was also invited to come back for a trial period. By contrast, Joe, the Black tester, found that “they are only looking for experienced-line cooks.” Joe wrote, “I started to try and convince him to give me a chance but he cut me off and said I didn't qualify.”

None of the testers had direct experience with kitchen work, but the White and Latino applicants were viewed as viable prospects while the Black applicant was rejected because he lacked experience. The shifting standards used by employers, offering more latitude to marginally skilled White applicants than similarly qualified minorities, suggests that even the evaluation of “objective” information can be affected by underlying racial considerations (see Pager, Western, & Bonikowski, 2009).

The shifting standards we witness in these interactions are less consistent with a model of traditional prejudice than with a more contingent and subtle conceptualization of racial attitudes. According to Dovidio and Gaertner's (2004) theory of aversive racism, for example, many individuals in contemporary society experience few conscious anti-Black sentiments, and traditional measures of prejudice have substantially declined. At the same time, there remains a high level of generalized anxiety or discomfort with Blacks that can shape interracial interaction and decision-making. Fueled largely by unconscious negative associations rather than overt forms of prejudice, aversive racism represents a more subtle and difficult-to-identify form of bias. Aversive racists believe in equality and consciously eschew distinctions on the basis of race; unconscious bias, however, leads to situations in which subtle forms of discrimination persist without the actor's awareness (see also Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986). In a laboratory experiment simulating a hiring situation, for example, the authors found little evidence of discrimination in cases where Black and White applicants were either highly qualified or poorly qualified for the position. When applicants had acceptable but ambiguous qualifications, however, participants were nearly 70% more likely to recommend the White applicant than the Black applicant (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2000; see also Hodson, Dovidio, & Gaertner, 2002). Few of the participants seemed to categorically believe that Whites were better employees than Blacks; in the context of uncertainty, however, race provided a kind of tie-breaker. Assessments of person-specific traits or characteristics, then, can take on different meanings when evaluated in the context of group-based expectations. Particularly in assessing characteristics with some degree of ambiguity—something that characterizes many of the qualities or skills expected of low-wage workers—employers may be more heavily influenced by prior expectations or unconscious stereotypes in forming their evaluations (see also Biernat & Kobrynowicz, 1997; Darley & Gross, 1983).

The fact that employers’ preferences and biases are more often manifested through subtle and dynamic interactions, rather than outright rejection of minority candidates, itself poses problems for the enforcement of antidiscrimination law. It is extremely difficult to find evidence of intent—often a prerequisite to a successful antidiscrimination case—when an employer does not consciously intend to exclude Blacks, but instead selectively attends to information that presents a more favorable impression of White candidates. This complex process of discrimination is far more difficult to document in legal cases, leaving a more limited range of possible remedies for subtle and unconscious discrimination. Indeed, with both job seeker and employer often unaware that any systematic bias is in effect, it becomes difficult to remedy subtle forms of discrimination without more proactive efforts at monitoring and enforcing the requirements of antidiscrimination law.

Field Experiments for the Purposes of Enforcement

The use of field experiments in research on discrimination represents an important tool for informing both social science and public opinion. The experimental method offers a clean design with which to assess causal effects, while simultaneously providing simple and straightforward measures of discrimination that can be easily understood by a lay audience. Given recent public-opinion surveys that demonstrate widespread skepticism over the persistence of discrimination, research of this kind can play an important role by providing “clear and convincing evidence” that discrimination remains an important feature of contemporary U.S. labor markets. Indeed, more than 80% of White respondents indicate that Blacks have “as good a chance as White people . . . to get any kind of job for which they are qualified,” and similar proportions believe that Blacks are not discriminated against in access to housing or managerial jobs. Respondents are more evenly split when asked about whether Blacks are treated fairly by the police (53% agree) (Schuman et al., 1997, p. 159–160). To the extent that public opinion concerning the relevance of discrimination shapes support for public policy efforts to address racial bias, the existence of reliable and accessible evidence on this question can play a potentially important role in shaping policy discussions.

At the same time, the field experimental approach can also play a more active role in support of antidiscrimination law and policy. Indeed, the audit method was initially designed for the enforcement of antidiscrimination law. Testers have been used to detect racially discriminatory practices among real estate agents, landlords, and lenders, providing evidence of differential treatment for use in litigation. In these discrimination cases, testers serve as the plaintiffs. Despite the fact that the testers themselves were not in fact seeking employment (or housing) at the time their application was submitted, their treatment nevertheless represents an actionable claim. This issue has received close scrutiny by the courts, including rulings by the highest federal courts (e.g., Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363, 373, 1982).

The differences between audit studies for research purposes and those used for enforcement are subtle, but are worth careful attention. Audit studies for research purposes are oriented not toward a specific intervention, but rather to obtaining accurate measures of the prevalence of discrimination across a broad sector or metropolitan area. The interest is in average treatment effects rather than in isolating discriminatory treatment at any single firm or agency. Studies of this kind typically include no more than a single audit per employer, with discrimination detected through systematic patterns across employers, rather than repeated acts of discrimination by a single employer. The design of research-based audit studies has important implications for what kinds of conclusions we can draw from their results. From research based audit studies, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the discriminatory tendencies of any given employer. Indeed, even a nondiscriminatory employer, when forced to choose between two equally qualified candidates, will choose the White applicant half the time. Only by looking at generalized patterns across a large number of employers can we determine whether hiring appears systematically influenced by race or other stigmatizing characteristics. The point of research based audit studies, then, is to assess the prevalence of discrimination across the labor market, rather than to intervene in particular sites of discrimination.

Testing for litigation, by contrast, requires multiple audits of the same employer (or real estate agent, etc.) to detect consistent patterns of discrimination by that particular individual and/or company. Recognizing that single-audit outcomes may be affected by chance or circumstance, building a case against an individual employer requires repeated measures of differential treatment that systematically bias one group relative to another. This approach often requires the recruitment of a much larger number of testers (and/or resume pairs) so that multiple unique-tester pairs can visit the employer without arousing suspicion. The conceptual underpinnings across audit types are very similar, but their design and implementation diverges considerably. Remaining cognizant of the goals and possibilities of each approach is important in constructing an appropriate study design.

Why isn't Testing Used More?

Testing has been used as a research tool and an enforcement mechanism by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to address discrimination in housing markets since the early 1970s. As recently as 1998, HUD allocated $7.5 million to fund a 20-city testing study measuring racial and ethnic discrimination in housing rental, sales, and lending markets, and to track changes over time according to testing measures of discrimination collected over the preceding two decades (Turner et al., 2002). Testing has been widely viewed as an effective vehicle for enforcing Fair Housing laws and for reducing the degree of active discrimination in housing markets (Turner et al., 2002; Yinger, 1995).

The case of employment has followed a very different path. In addition to the logistical concerns discussed above, employment testing has further been stymied by a hostile political environment that has limited the resources available for “testing” the prevalence of discrimination in labor markets. In 1997, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) announced a plan to launch a series of pilot employment audits across the country to support a more proactive model of enforcement of antidiscrimination law (http://www.eeoc.gov/press/12–5-97.html). Congressional leadership, at that time controlled by conservative house speaker Newt Gingrich, objected vehemently to this strategy of enforcement. According to Gingrich, “The use of employment testers, frankly, undermines the credibility of the EEOC. The government should not sanction applicants’ misrepresentation of their credentials to prospective employers. The use of testers not only causes innocent businesses to waste resources (interviewing candidates not interested in actual employment), but also puts a government agency in the business of entrapment. It assumes guilt where there has been no indication of discriminatory behavior (Gingrich, 1998)” That year's budget appropriations bill provided funding for the EEOC conditional on eliminating of the use of testing. Unlike the arena of housing discrimination, in which dozens of federally sponsored testing studies have taken place, the use of the audit methodology for both research and litigation in the area of employment discrimination has thus remained negligible.

The ethical concerns raised by Gingrich are important and should not be dismissed out of hand. Indeed, audit studies require that employers are unwittingly recruited for participation and then led to believe that the testers are viable job candidates. Time spent reviewing applications and/or interviewing applicants will therefore impose a cost on the subject. Most employment audit studies limit their samples to employers for entry-level positions—those requiring the least intensive review—in part to minimize the time employers spend evaluating phony applicants. The field experiments reported in this article further limited imposition on employers by restricting audits to the first stage of the employment process. Candidate reviews in these cases typically consisted of no more than a short review of the application and/or resume and, in a smaller fraction of cases, a short interview (Pager, 2003; Pager et al., 2009; see Pager 2007 for a more extensive discussion of ethical issues related to audit research).

While the costs to employers should not be overlooked, they must also be examined relative to the possible benefits resulting from this approach. As noted earlier, in the absence of some form of proactive investigation, hiring discrimination remains extremely difficult to identify or address. Job applicants typically have too little information at their disposal to make credible claims, and employers can easily come up with reasonable post hoc justifications for hiring decisions in individual cases. It is only through repeated observation of systematic hiring bias that discrimination at the early stages of the hiring process can be reliably identified and remedied. Recently, the EEOC has shown signs of renewed interest in pursuing a testing program. It remains to be seen whether, within the prevailing political climate, this preliminary agenda can be realized.

Discussion

By focusing on discrimination at the point of hire, field experiments uncover an important and much under-investigated source of racial disadvantage in the labor market. According to the results of our experiments, Blacks are less than half as likely to receive consideration by employers relative to equally qualified Whites across a wide range of low-wage jobs. Though the subtle nature of contemporary discrimination in most cases leaves applicants unaware of differential treatment, the ultimate distribution of employment opportunities across equally qualified applicants reveals a process of decision-making very much shaped by race. This research emphasizes the need for direct measures of discrimination in real-life settings; and suggests that enforcement efforts that rely on reactive claims will miss much of the discrimination that takes place in labor markets today.

Of course field experiments are not appropriate for measuring all types of discrimination. Discrimination at higher levels of the corporate hierarchy and among jobs filled through personal networks is less identifiable using this methodology. Likewise, the many informal channels through which preferences and biases are enacted in the workplace are difficult to document using an audit methodology (Collins, 1989). For a complete picture of discrimination in labor markets, then, we require a range of methodological approaches and perspectives. This essay focuses on the merits of the audit methodology as a tool for both research and enforcement of discrimination in employment. Complementing other approaches, this methodology has much to offer in pursuing the goal of equal access to employment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by generous grants from NIH (K01HD53694) and NSF (CAREER 0547810).

Biography

DEVAH PAGER is an Associate Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of the Joint Degree Program in Social Policy at Princeton University. Her research focuses on institutions affecting racial stratification, including education, labor markets, and the criminal justice system. Pager's recent research has involved a series of field experiments studying discrimination against minorities and ex-offenders in the low wage labor market. Her book, Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in an Era of Mass Incarceration (University of Chicago, 2007), investigates the racial and economic consequences of large-scale imprisonment for contemporary U.S. labor markets. Pager holds Masters Degrees from Stanford University and the University of Cape Town, and a PhD from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

BRUCE WESTERN is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. His research interests are in the field of social stratification and inequality, political sociology, and statistical methods. He is the author of Punishment and Inequality in America, a study of the growth and social impact of the American penal system. His first book, Between Class and Market, examined the development and decline of labor unions in the postwar industrialized democracies. He is currently studying the social impact of rising-income inequality in the United States. Western taught at Princeton from 1993 to 2007 and received his PhD in sociology from UCLA.

Contributor Information

Devah Pager, Princeton University.

Bruce Western, Harvard University.

References

- Ayres I, Siegelman P. Race and gender discrimination in bargaining for a new car. American Economic Review. 1995;85:304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bendick M, Jr., Jackson C, Reinoso V, Hodges L. Discrimination against Latino job applicants: A controlled experiment. Human Resource Management. 1991;30:469–484. doi: 10.1002/hrm.3930300404. [Google Scholar]

- Bendick M, Jr., Jackson C, Reinoso V. Measuring employment discrimination through controlled experiments. Review of Black Political Economy. 1994;23:25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bendick M, Jr., Nunes A. Developing the research basis for controlling bias in hiring. Journal of Social Issues. 2012;68(2):238–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01747.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. The American Economic Review. 2004;94:991–1013. doi: 10.1257/0002828042002561. [Google Scholar]

- Biernat M, Kobrynowicz D. Gender and race-based standards of competence: Lower minimum standards but higher ability standards for devalued groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:544–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.544. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancio A, Silvia T, Evans D, Maume D. Reconsidering the declining significance of race: Racial differences in early career wages. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:541–56. doi: 10.2307/2096391. [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. The marginalization of Black executives. Social Problems. 1989;36:317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F. The denial of personal discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist. 1984;27:371–386. doi: 10.1177/000276484027003008. [Google Scholar]

- Cross H, Kenney G, Mell J, Zimmerman W. Employer hiring practices: Differential treatment of hispanic and Anglo job seekers. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Darley J, Gross P. A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:20–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.20. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue John J., III, Siegelman P. The changing nature of employment discrimination litigation. Stanford Law Review. 1991;43:983–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio J, Gaertner S. Aversive racism and selection decisions. Psychological Science. 2000;11:315–319. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00262. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio J, Gaertner S. Aversive racism. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 36. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2004. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer R, Jr., Levitt S. The causes and consequences of distinctively Black names. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2004;119:767–805. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. The aversive form of racism. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1986. pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich N. Testimony of House Speaker Newt Gingrich before the House Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations on “The Future Direction of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,”. 1998 Mar 3; 1998 Retrieved from: http://www.house.gov/ed_workforce/hearings/105th/eer/eeoc3398/gingrich.htm.

- Heckman J. Detecting discrimination. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1998;12:101–116. doi: 10.1257/jep.12.2.101. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G, Vicknair K. Appropriate tests of racial wage discrimination require controls for cognitive skill: Comment on Cancio, Evans, and Maume. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:557–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ford R. The Race Card. Picador; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson G, Dovidio J, Gaertner S. Processes in racial discrimination: Differential weighting of conflicting information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:460–471. doi: 10.1177/0146167202287004. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenman J, Neckerman K. We'd love to hire them, but . . . : The meaning of race for employers. In: Jencks C, Peterson P, editors. The Urban Underclass. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- LaPiere R. Attitudes versus actions. Social Forces. 1934;13:230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt S, List J. What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2007;21:153–174. doi: 10.1257/jep.21.2.153. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D, Lundy G. Use of Black English and racial discrimination in urban housing markets: New methods and findings. Urban Affairs Review. 2001;36:452–469. doi: 10.1177/10780870122184957. [Google Scholar]

- Moss P, Tilly C. Stories employers tell: Race, skill, and hiring in America. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark D. Sex discrimination in restaurant hiring: An audit study. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996;111:915–941. doi: 10.2307/2946676. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L, Nelson R. Scaling the pyramid: A sociolegal model of employment discrimination litigation. In: Nielsen LB, Nelson RL, editors. Handbook of employment discrimination research. Springer; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2005. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108:937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Quillian L. Walking the talk: What employers say versus what they do. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:355–380. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000301. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The use of field experiments for studies of employment discrimination: Contributions, critiques, and directions for the future. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2007;609:104–133. doi: 10.1177/0002716206294796. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Western B, Bonikowski B. Discrimination in a low wage labor market: A field experiment. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:777–799. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400505. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Karafin D. Bayesian bigot? Statistical discrimination, stereotypes, and employer decision-making. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences. 2009;621:70–93. doi: 10.1177/0002716208324628. doi: 10.1177/0002716208324628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner R. The efficiency and efficacy of Title VII. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 1987;136:513–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley S, Bayton J, Outtz J. Taxi service in the district of Columbia: Is it influenced by Patrons’ race and destination? Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under the Law; Washington, DC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Steeh C, Bobo L, Krysan M. Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D, Wright S, Moghaddam F, Lalonde R. The personal/group discrimination discrepancy: Perceiving my group, but not myself, to be a target for discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1990;16:254–262. doi: 10.1177/0146167290162006. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Fix M, Struyk R. Opportunities denied, opportunities diminished: Racial discrimination in hiring. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Skidmore F. Mortgage lending discrimination: A review of existing evidence. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Ross S, Gaister G, Yinger J. Urban Institute, Department of Housing and Urban Development; Washington, DC: 2002. Discrimination in metropolitan housing markets: National results from Phase 1 HDS 2000. Retrieved from: http://www.huduser.org/intercept.asp?loc=/Publications/pdf/Phase1_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger R, Lichter M. How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. The University of California Press; California: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. Vintage Books; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yinger J. Closed doors, opportunities lost: The continuing costs of housing discrimination. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]