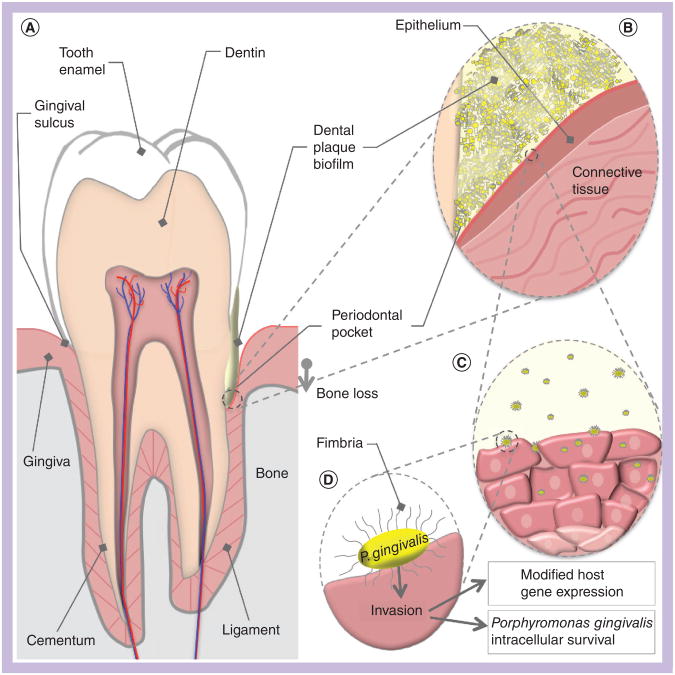

Figure 1. Porphyromonas gingivalis host environment and interactions.

(A) A cross-sectional schematic diagram of a human tooth. The periodontium is composed of the gingiva (pink) and the alveolar bone (grey). The left side represents periodontal health, while the right represents the changes that occur in periodontitis. Dental plaque is represented in yellow, in contact with the gingiva and tooth surfaces. Development of a chronic host inflammatory response ultimately results in a loss of connection between the gingiva and the root surface, creating a periodontal pocket. Bone is also resorbed as the bacteria advance down the surface of the tooth. (B) A magnified view of the periodontal pocket. The biofilm (yellow) is composed of many species of bacteria, of which Porphyromonas gingivalis is a small portion. P. gingivalis in the biofilm comes into direct contact with gingival epithelium. Secretion of P. gingivalis gingipains aids in the destruction of host antibodies and complement, and contributes to localized tissue destruction. (C) A number of P. gingivalis cells may leave the biofilm community and invade host cells. Internalized bacteria move from cell to cell into the deeper layers of the connective tissue. (D) Major fimbriae on the bacterial cell surface act as adhesins for host integrin receptors, and mediate internalization of the bacteria into the host cell cytoplasm. Postinvasion host cell gene expression is significantly modified; for example, reductions in cytokine production interferes with neutrophil recruitment to the periodontal pocket. The ability of P. gingivalis to modify local host responses to the biofilm flora results in the skewed immune response that drives periodontitis progression.