Abstract

PURPOSE

Erectile dysfunction (ED) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) share etiology and pathophysiology. The underlying pathology for preoperative ED may adversely affect survival following radical prostatectomy (RP). We examined the association between preoperative ED and survival following RP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 1983 and 2000, a single surgeon performed RP on 2511 men, with preoperative ED (ED group, n = 231, 9.2%) or without ED (No ED group, n = 2280, 90.8%). We retrospectively analysed their CVD-specific survival (CVDSS), prostate cancer-specific survival (PCSS), non-PCSS (NPCSS) and overall survival (OS) from time of surgery.

RESULTS

With median follow-up of 13 years after RP, 449 men (18%) died (140 from prostate cancer, 309 from other causes). Kaplan–Meier analyses demonstrated significant differences in CVDSS (P < 0.001), NPCSS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001), but not in PCSS (P = 0.12), between the ED group vs No ED group. In univariate proportional hazards analyses, preoperative ED was associated with a significant decrease in OS, hazard ratio (HR), 1.71 (95% CI, 1.34–2.23), P < 0.001. However, in multivariable analyses, the association of ED with survival became non-significant (HR, 1.25 (95% CI, 0.97–1.66), P = 0.111) after adjusting for other prognostic factors, such as age, preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, Gleason score, pathologic stage, body mass index and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

CONCLUSIONS

Preoperative ED is associated with decreased overall survival and survival from causes other than prostate cancer following RP. However, preoperative ED was not an independent predictor of overall survival after adjusting for other predictors of survival. Urologists should carefully assess pretreatment ED status to enhance appropriate treatment recommendation for men with prostate cancer.

Keywords: Erectile dysfunction, survival, radical prostatectomy, prostate cancer

INTRODUCTION

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is a common treatment modality for men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Although RP provides excellent cancer control, up to 40% of these men may recur biochemically with a detectable serum PSA in long-term follow-up [1]. Although the freedom from biochemical recurrence has frequently been used as a surrogate for treatment success, the ultimately desired outcome following surgery is prolonged survival. However, it is challenging to accurately predict survival, particularly from non-prostate cancer causes because of the relative paucity of well-characterized, modern surgical cohorts with sufficient follow-up.

Like prostate cancer, erectile dysfunction (ED) is a common urologic condition [2]. Recently, Thompson et al. demonstrated that ED is a harbinger of cardiovascular events in a prospective study [3]. Therefore, we hypothesized that preoperative ED may be associated with lower survival following RP. We evaluated a large cohort of men with known preoperative ED who underwent RP by a single surgeon in the modern era. We assessed the association between ED and survival following RP, after adjusting for other potential predictors of survival.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

Between 1983 and 2000, 2718 men underwent RP with staging pelvic lymphadenectomy by a single surgeon (PCW) for clinically localized prostate cancer. The data were captured prospectively with institutional review board (IRB) approval. Preoperatively, patient age, serum PSA level, clinical stage, and biopsy Gleason score (tumor grade) were included in the database. Preoperative body-mass index (BMI) was abstracted from medical records. At the time of urological consultation several weeks to months before surgery, the surgeon assessed men for the presence of ED, defined as an inability to perform sexual intercourse. Preoperative ED status was categorized as ‘No ED’, ‘ED’, ‘No partner’, or ‘Questionable’ because of insufficient information to definitively establish ED status. Excluded from analysis were 99 men without a sexual partner (‘No partner’) and 108 men with questionable ED (‘Questionable’). A total of 2511 men (92.4%) remained for analysis of the association between ED and survival. Erectile function was assessed in 2507 out of 2511 men (99.8%) without the use of selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5).

Immediately following surgery, RP specimens were examined histologically in a standard fashion to determine and capture tumor grade (Gleason score) and stage information, such as extraprostatic extension status, seminal vesicle and lymph node involvement status and surgical margin status.

Men were followed postoperatively for recurrence, either at our institution or by referring physicians, with serum PSA determinations and rectal examinations every 3 months for the first year, semi-annually for the second year and annually thereafter. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant, hormonal or radiation therapy information was also captured in the database.

Mortality status and cause of death information were updated using medical records and the US Government vital statistics record using the National Death Index (NDI) and the Social Security Administration (SSA) Death Master File. The NDI is a central computerized index of death record information on file by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/ndi/about_ndi.htm). It has served as an accurate resource to aid epidemiologists and other health and medical investigators with mortality ascertainment [4]. The SSA Death Master File contains the dates of birth and death. Mortality was considered to be caused by prostate cancer if a man had prostate cancer as the underlying cause of death or had hormone refractory metastatic disease at the time of death. Mortality was considered to be caused by cardiovascular disease (CVD) if a man had ischemic heart disease, dysrhythmia, heart failure, cardiac arrest, atherosclerosis, cerebrovascular disease or other cardiovascular conditions as the underlying cause of death. Comorbidity data were obtained using the secondary diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM) in the discharge records [5]. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated to stratify men according to their health status at the time of RP [6].

STATISTICAL METHODS

Comparisons between subgroups of men were performed using χ2 tests for categorical data, and t-tests or analysis of variance for continuous data. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using the logrank test. Because overall survival (OS) was the primary focus of this study, it was analysed using multivariable proportional hazards models to control for other prognostic and confounding factors. Because of the observational retrospective nature of this study, men with and without ED may differ with respect to established prognostic factors for survival (age, comorbidity, year of surgery, tumor stage and Gleason score). Given the established importance of these variables, they were considered a priori as potential confounding factors to be controlled in multivariable models. Secondary outcomes such as prostate cancer-specific survival (PCSS) and non-PCSS (NPCSS) were evaluated only in a univariate fashion with Kaplan–Meier survival estimates. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

The analysis included 231 (9.2%) men with ED (ED group) and 2280 men (90.8%) without ED (No ED group) before the surgery. Median follow-up from the date of surgery was 13 years (range 1–25), and 33% of men had ≥ 15 years of follow-up. A total of 140 men (5.6%) died from prostate cancer while 309 (12.3%) died from other causes during the period of observation. Only 60 men (2.4%) died from cardiovascular events.

Men with known ED status (ED group or No ED group) and those lacking definitive ED status (No partner or Questionable groups) were similar with respect to age at the time of surgery (P = 0.06), comorbidity status (P = 0.16), and Gleason score (P = 0.32) (data not shown). However, they differed with respect to year of surgery (P < 0.001), PSA at diagnosis (P = 0.02) and pathologic stage (P < 0.001). More importantly, they were similar with respect to OS (P = 0.29), PCSS (P = 0.22) and NPCSS (P = 0.67).

The two study groups (ED group and No ED group) were similar with respect to BMI, PSA concentration, Gleason score and race (Table 1). They differed significantly with respect to age, year of surgery, tumor stage and comorbidity status (Table 1). Notably, men with ED were older (63 vs 57 years, P < 0.001) and less likely to have organ-confined disease (42% vs 52%, P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of 2511 men who underwent radical prostatectomy between 1983 and 2000 with available preoperative erectile dysfunction status

| ED group | No ED group | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 231 (9.2) | 2280 (90.8) | 2511 (100) | |

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | |||

| <40 | 0 (0) | 24 (1) | 24 (0.9) | |

| 41–50 | 3 (1.3) | 345 (15.1) | 348 (13.9) | |

| 51–60 | 58 (25.1) | 1107 (48.6) | 1165 (46.4) | |

| 61–70 | 161 (69.7) | 788 (34.6) | 949 (37.8) | |

| >70 | 9 (3.9) | 16 (0.7) | 25 (1.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.31 | |||

| <25 | 66 (32.0) | 800 (37.8) | 866 (37.3) | |

| 25–30 | 115 (55.8) | 1131 (53.4) | 1246 (53.6) | |

| >30 | 25 (12.1) | 186 (8.8) | 211 (9.1) | |

| RRP year | <0.001 | |||

| 1983–1990 | 114 (49.3) | 786 (34.5) | 900 (35.8) | |

| 1991–2004 | 117 (50.7) | 1495 (65.5) | 1615 (64.2) | |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 0.46 | |||

| 0–2.6 | 23 (11.7) | 318 (15.7) | 341 (15.2) | |

| 2.6–4 | 26 (13.2) | 240 (11.8) | 266 (11.9) | |

| 4–10 | 97 (49.2) | 1037 (50.8) | 1134 (50.7) | |

| 10–20 | 40 (20.3) | 348 (17.0) | 388 (17.3) | |

| >20 | 11 (5.6) | 99 (4.9) | 110 (4.9) | |

| TNM stage | <0.001 | |||

| T1a/b | 30 (13.0) | 137 (6.0) | 167 (6.7) | |

| T1c | 65 (28.1) | 886 (38.9) | 951 (37.9) | |

| T2 | 132 (57.1) | 1204 (52.9) | 1336 (53.3) | |

| T3 | 4 (1.7) | 50 (2.2) | 54 (2.2) | |

| Biopsy Gleason score | 0.22 | |||

| 2–6 | 170 (75.2) | 1804 (80.4) | 1974 (79.9) | |

| 7 | 47 (20.8) | 366 (16.3) | 413 (16.7) | |

| 8–10 | 9 (3.9) | 75 (3.3) | 84 (3.4) | |

| Race | 0.56 | |||

| Caucasian | 223 (96.6) | 2158 (94.7) | 2381 (94.8) | |

| African American | 4 (1.7) | 59 (2.6) | 63 (2.5) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 6 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | |

| Others | 3 (1.3) | 53 (2.3) | 56 (2.2) | |

| Pathologic stage | <0.001 | |||

| pT2 (OC) | 98 (42.4) | 1189 (52.3) | 1287 (51.4) | |

| pT3a (EPE) | 94 (40.7) | 844 (37.2) | 938 (37.5) | |

| pT3b (SVI) | 21 (9.1) | 105 (4.6) | 126 (5.0) | |

| LN+ | 18 (7.8) | 134 (5.9) | 152 (6.1) | |

| Gleason score from RRP | 0.24 | |||

| 2–6 | 133 (57.6) | 1418 (62.5) | 1551 (62.0) | |

| 7 | 76 (32.9) | 692 (30.5) | 768 (30.7) | |

| 8–10 | 22 (9.5) | 160 (7.1) | 182 (7.3) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0.03 | |||

| 0 | 185 (81.5) | 1977 (87.5) | 2162 (86.9) | |

| 1 | 33 (14.5) | 218 (9.7) | 251 (10.1) | |

| >2 | 9 (3.7) | 65 (2.9) | 74 (3.0) | |

| Overall survival | ||||

| Alive | 161 (69.7) | 1884 (82.6) | 2045 (81.4) | |

| Dead | 70 (30.3) | 396 (17.4) | 466 (18.6) | |

| Mean follow-up (years, range) | 13.4 (0–23) | 13.4 (0–25) | 13.4 (0–25) | |

ED, erectile dysfunction; No ED, no erectile dysfunction; BMI, body-mass index; EPE, extra-prostatic extension; OC, organ confined; SVI, seminal vesicle involvement; LN, lymph nodes, RRP, radical retropubic prostatectomy.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL (CVDSS)

Thirteen men (5.6%) died from CVD in the ED group while 47 men (2.1%) died from CVD in the No ED group. There was a small, yet statistically significant, difference in CVDSS (P < 0.001) between the ED and No ED groups. The 10- and 20-year Kaplan–Meier estimates of CVDSS are 0.98 and 0.91 for the ED group, 0.99 and 0.95 for the No ED group, respectively.

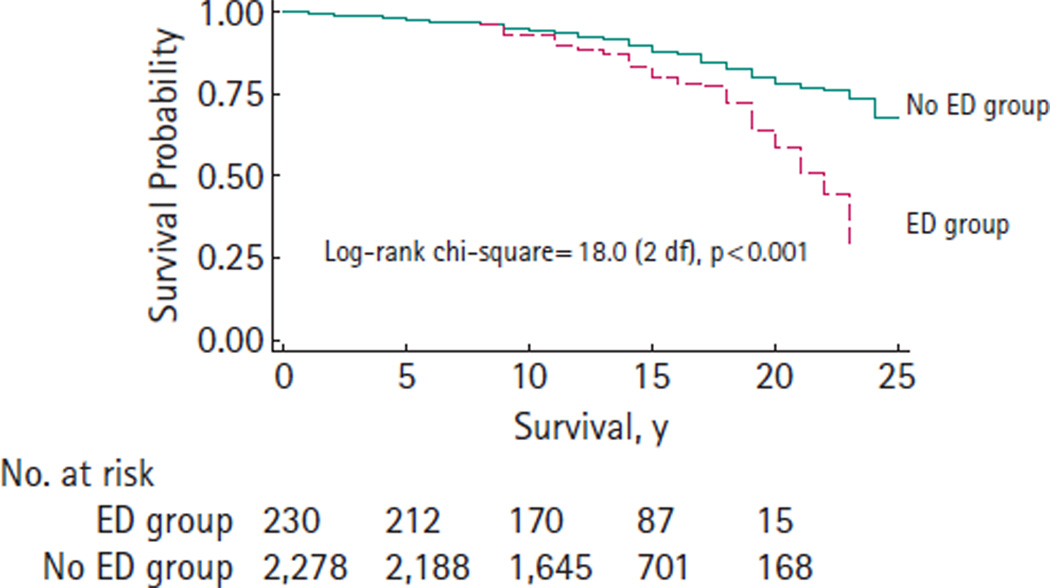

NON-PROSTATE CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL (NPCSS)

A total of 51 men (22.1%) died from non-prostate cancer related causes in the ED group while 258 men (11.3%) died from non-prostate cancer related causes in the No ED group. Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrate significant differences in NPCSS (P < 0.001) between the ED group and the No ED group (Fig. 1). Notably, the curves are nearly identical up to 10 years after RP. The 10- and 20-year NPCSS estimates are 0.93 and 0.59 for the ED group, 0.95 and 0.79 for the No ED group, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Non-prostate cancer-specific survival after radical prostatectomy (1983–2000).

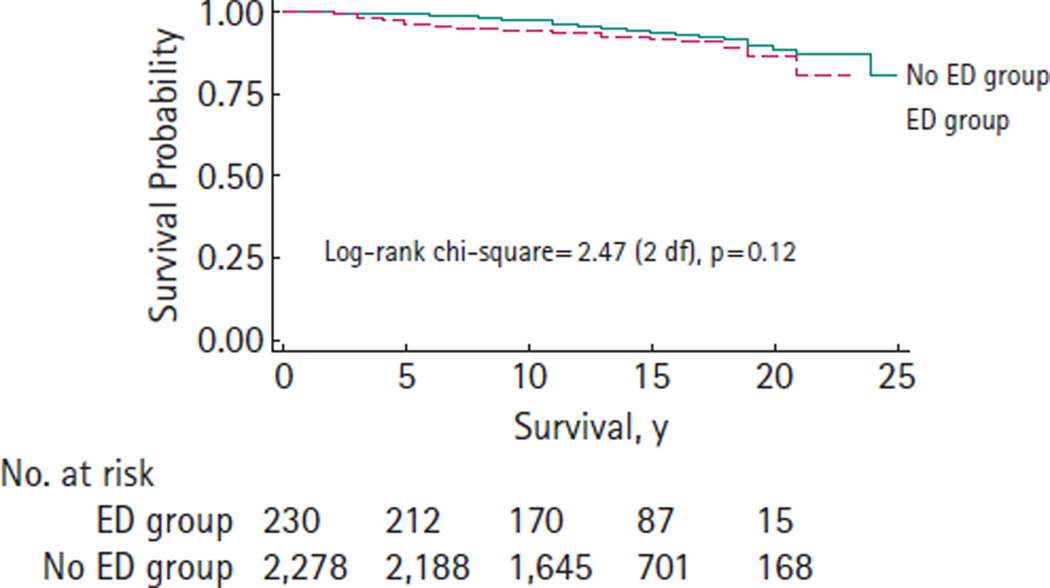

PROSTATE CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL (PCSS)

Eighteen men (7.8%) died from prostate cancer in the ED group while 122 men (5.4%) died from prostate cancer in the No ED group. There was no significant difference in PCSS (P = 0.12) between the ED group and No ED group (Fig. 2). The 10- and 20-year PCSS estimates are 0.95 and 0.86 for the ED group, 0.97 and 0.88 for the No ED group, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Prostate cancer-specific survival after radical prostatectomy (1983–2000).

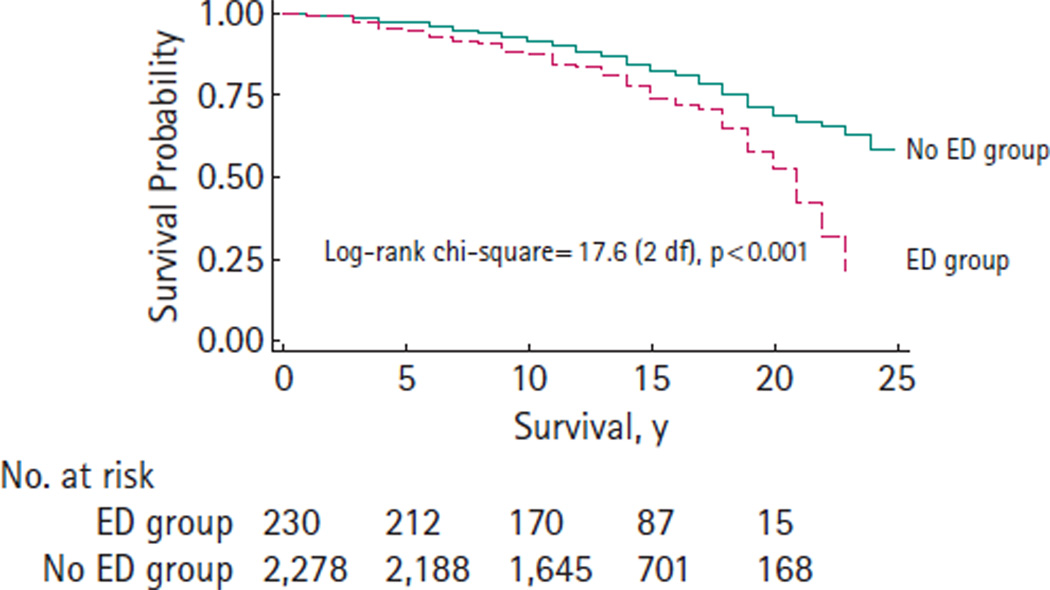

OVERALL SURVIVAL (OS)

There was a significant difference in OS (P < 0.001) between the ED group and No ED group (Fig. 3). The 10- and 20-year OS estimates are 0.88 and 0.53 for the ED group, 0.92 and 0.69 for the No ED group, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Overall survival after radical prostatectomy (1983–2000).

PROPORTIONAL HAZARDS MODELS

Univariate proportional hazards models demonstrated significant associations with overall mortality for age, year of surgery, Gleason score and pathological stage (Table 2). Preoperative ED was associated with a 71% increase in overall mortality, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.71, P < 0.001. Neither BMI nor CCI were statistically significant prognostic factors in the univariate analyses.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariable proportional hazards models of risk of overall mortality (survival time measured from date of surgery), 1983–2000

| Univariate models |

Multivariable model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age | 1.07 (1.05, 1.08) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative ED | 1.71 (1.34, 2.23) | <0.001 | 1.25 (0.97, 1.66) | 0.111 |

| Year of surgery | 0.90 (0.88, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.89, 0.94) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative GS: | ||||

| 7 vs <7 | 1.96 (1.60, 2.39) | <0.001 | 1.50 (1.20, 1.87) | <0.001 |

| 8–10 vs <7 | 3.84 (2.96, 4.97) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.80, 3.21) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | ||||

| 25–30 vs <25 | 1.07 (0.87, 1.32) | 0.50 | – – | – – |

| >30 vs <25 | 1.16 (0.82, 1.64) | 0.41 | – – | – – |

| Postoperative stage | ||||

| EPE vs OC | 1.59 (1.29, 1.98) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.94, 1.48) | 0.15 |

| SVI vs OC | 3.23 (2.34, 4.47) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.21, 2.44) | 0.003 |

| LN positive vs OC | 4.43 (3.32, 5.89) | <0.001 | 2.54 (1.84, 3.52) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 1 vs 0 | 1.29 (0.97, 1.73) | 0.08 | – – | – – |

| 2+ vs 0 | 0.91 (0.50, 1.66) | 0.76 | – – | – – |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ED, erectile dysfunction; EPE, extra-prostatic extension; GS, Gleason score; OC, organ confined; SVI, seminal vesicle involvement; LN, lymph nodes; ‘– –’ indicates variables that were not statistically significant in the multivariable model.

The multivariable proportional hazards model demonstrated significant associations with overall mortality for age, year of surgery, Gleason score and pathological stage (Table 2). Although preoperative ED was associated with increased risk of death, it was no longer statistically significant (HR = 1.25, P = 0.111).

DISCUSSION

Erectile dysfunction is a common urological condition affecting an estimated 30 million men in the USA alone [7]. Both ED and CVD share common risk factors such as age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia [3,8–10]. Healthy men with ED have reduced coronary flow reserve, which is one of the early signs of coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis [11]. In the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial involving men aged 55 years or older, incident ED was associated with increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular events during study follow-up [3]. In a Dutch population-based study, baseline prevalent ED status, assessed using a single question on erectile rigidity, was an independent predictor of subsequent cardiovascular events such as acute myocardial infarction, stroke and sudden death [12]. Therefore, ED is considered as a manifestation of endothelial dysfunction and a potential harbinger of cardiovascular abnormality [3].

Prostate cancer is also one of the most common urological conditions [13]. When a man is newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, his ED status is carefully evaluated as the recovery or preservation of potency following brachytherapy [14], external beam radiation therapy [15], or radical prostatectomy [16] is strongly associated with pretreatment ED status.

Radical prostatectomy is recommended for men with clinically localized cancer and reasonable life expectancy [17]. However, it is challenging to assess life expectancy objectively and accurately [18]. Fortunately, there are known predictors of overall survival such as age and comorbidity [19]. Known predictors of PCSS following surgery include PSA, Gleason grade and stage, although a relatively small proportion of men will die from their prostate cancer after surgery [20]. Accurate prediction of life expectancy will help determine the best treatment option for men with incident prostate cancer.

In this study, we investigated the association of preoperative ED with survival outcomes in a retrospective cohort of more than 2500 men who underwent RP by a single surgeon. With median follow-up of 13 years after surgery, preoperative ED exhibited significant univariate associations with decreased OS and NPCSS, but not with PCSS. In addition, preoperatively potent men experienced a small, yet statistically significant, survival advantage from CVDs. However, in multivariable analyses, ED was not an independent predictor of OS.

In clinical practice, ED status is one of the most important questions that urologists ask men with incident prostate cancer, as their ED status may influence the recommendation for a nerve-sparing approach for RP. Although our study did not find ED status to be an independent predictor of overall survival following surgery, ED status may be a simple indicator that integrates a number of risk factors for mortality, enabling urologists to consider it as a potential surrogate marker for shorter life expectancy in men considering treatment for prostate cancer. The presence of ED in an apparently healthy man should cause heightened scrutiny for underlying CVD. This is underscored by the recent report from Sweden suggesting that a new diagnosis of prostate cancer is itself associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events for up to 1 year after diagnosis [21].

This study does not suggest that ED is a contraindication to surgical treatment for men with prostate cancer. In this study, preoperative ED status was not associated with PCSS. For example, Kaplan–Meier estimates of 15-year PCSS were 92% and 93% in the ED group and No ED group, respectively.

How do the findings of this study apply to potent men with a newly diagnosed prostate cancer? Obesity, sedentary lifestyle and smoking are well known to be associated with subsequent risk of developing ED and lifestyle modification, such as weight loss and regular exercise, can result in maintenance or improvement in sexual function [22,23]. Potent men have better recovery or preservation of potency following treatment for prostate cancer. Erectile dysfunction also affects non-surgical risks and may precede a cardiovascular event by up to 5 years in almost half of men with ED [24]. Our data now suggest that preoperative ED status may be a surrogate marker for a shorter life expectancy. Therefore, potent men have one more tangible, strong incentive to initiate or maintain a healthy lifestyle.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the association between preoperative ED and survival following surgery. Preoperative ED status was adversely associated with OS and NPCSS, but not PCSS, after surgery. It will be intriguing to study whether pretreatment ED status is also associated with lower survival following non-surgical treatment for prostate cancer.

Several potential limitations of this study deserve mention. First, a single question was used to assess ED status instead of more commonly used, validated tools such as the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) [25,26]. Salonia et al. recently reported a significant proportion of men undergoing RP who reported themselves to be potent preoperatively actually met the criteria for ED based on IIEF [27]. However, a single, direct question, although potentially lacking in psychometric validation, has been proven to be reliable in assessing ED status in a population-based study [28]. In addition, the IIEF had not been developed when our surgical series began. In the current study, preoperative ED status was prospectively assessed and recorded by a single surgeon, minimizing interobserver bias. Second, we did not have complete information about medications with potential beneficial or detrimental effect on ED status, except for phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor use. In addition, we did not have information about other preoperative ED treatment such as vacuum erection device. However, when we limited the analyses to men who had surgery before 1998 when the PDE5 inhibitor became available, the study outcomes were not changed (data not shown). We defined potency as the ability to have intercourse without PDE5 inhibitors for most men (99.8%). Third, although preoperative ED status was associated with CVDSS, the number of overall mortalities from CVD was rather small in our series. Therefore, we did not perform multivariable analysis with CVDSS as an end point. Fourth, there were differences in the established prognostic factors between the two study groups. However, these prognostic factors were well controlled in our multivariable survival analyses. Fifth, the patient selection criteria for surgery were strict in our series. The patients were recommended to proceed with surgery when their overall health status was excellent with life expectancy of at least 10–15 years. Therefore, very few men in our series had significant comorbidities at the time of surgery. Finally, non-white men were underrepresented in our series. Therefore, our findings need to be validated using a population-based, diverse cohort.

In conclusion, preoperative ED is associated with lower OS and survival from causes other than prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy. Although preoperative ED was not an independent predictor of survival after adjusting for other established risk factors, it may provide a simple indicator that serves as a surrogate that integrates the effects of multiple risk factors. Urologists should continue to pay close attention to ED status during evaluation. Men with ED should be investigated for cardiovascular risk factors and targeted for strategies to prevent potential cardiovascular events.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body-mass index

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- ED

erectile dysfunction

- GS

Gleason score

- PCSS

prostate cancer-specific survival

- PDE5

phosphodiesterase type 5

- RP

radical prostatectomy

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared. Source of funding: this study was supported in part by funds from the National Cancer Institute Grant CA58236 SPORE in Prostate Cancer, the Jahnigen Career Development from the American Geriatrics Society (M. Han) and by gifts from Dr and Mrs Peter S. Bing (B. Trock).

REFERENCES

- 1.Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH Consensus Development. Panel on Impotence. NIH Consensus Conference. Impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Probstfield JL, Moinpour CM, Coltman CA. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2996–3002. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, McKinlay JB. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40-69 years old: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Urol. 2000;163:460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moinpour CM, Lovato LC, Thompson IM, Jr, et al. Profile of men randomized to the prostate cancer prevention trial: baseline health-related quality of life, urinary and sexual functioning, and health behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1942–1953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgquist R, Gudmundsson P, Winter R, Nilsson P, Willenheimer R. Erectile dysfunction in healthy subjects predicts reduced coronary flow velocity reserve. Int J Cardiol. 2006;112:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Bosch JL, et al. Erectile dysfunction prospectively associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population: results from the Krimpen Study. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:92–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward EM. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2009. [Accessed May 2009]. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/ 500809web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stock RG, Kao J, Stone NN. Penile erectile function after permanent radioactive seed implantation for treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:436–439. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantz CA, Song P, Farhangi E, et al. Potency probability following conformal megavoltage radiotherapy using conventional doses for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubbelman YD, Dohle GR, Schröder FH. Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a systematic review of prognostic indicators for a successful outcome. Eur Urol. 2006;50:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh PC. Radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer provides durable cancer control with excellent quality of life: a structured debate. J Urol. 2000;163:1802–1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson JR, Clarke MG, Ewings P, Graham JD, MacDonagh R. The assessment of patient life-expectancy: how accurate are urologists and oncologists? BJU Int. 2005;95:794–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albertsen PC, Fryback DG, Storer BE, Kolon TF, Fine J. The impact of comorbidity on life expectancy among men with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1996;156:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4300–4305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fall K, Fang F, Mucci LA, et al. Immediate risk for cardiovascular events and suicide following a prostate cancer diagnosis: prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito K, Giugliano F, Di Palo C, et al. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile dysfunction in obese men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:2978–2984. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–168. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodges LD, Kirby M, Solanski J, O’Donnell J, Brodie DA. The temporal relationship between erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;2007:2019–2025. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomon G, Isbarn H, Budaeus L, et al. Importance of baseline potency rate assessment of men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer prior to radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2009;6:498–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salonia A, Zanni G, Gallina A, et al. Baseline potency in candidates for bilateral nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2006;50:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derby CA, Araujo AB, Johannes CB, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB. Measurement of erectile dysfunction in population-based studies: the use of a single question self-assessment in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]