Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In May 2010, a new Canadian guideline on prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) was released. To assess changes in family physicians’ (FPs) prescribing of opioids following the release of the guideline, it is necessary to know their practices before the guideline was widely disseminated.

OBJECTIVES:

To determine FPs’ practices and knowledge in prescribing opioids for CNCP in relation to the Canadian guideline, and to determine factors that hinder or enable FPs in prescribing opioids for CNCP.

METHODS:

An online survey was developed and FPs who manage CNCP were electronically contacted through the College of Family Physicians of Canada, university continuing medical education offices and provincial regulatory colleges.

RESULTS:

A total of 710 responses were received. FPs followed a precautionary approach to prescribing opioids and already practiced in accordance with Canadian guideline recommendations by discussing adverse effects, monitoring for aberrant drug-related behaviour and advising caution when driving. However, FPs seldom discontinued opioids even if they were ineffective and were unaware of the ‘watchful dose’ of opioids, the daily dose at which patients may need reassessment or closer monitoring. Only two of nine knowledge questions were answered correctly by more than 40% of FPs. The main enabler to optimal opioid prescribing was having access to a patient’s opioid history from a provincial prescription monitoring program. The main barriers to optimal prescribing were concerns about addiction and misuse.

CONCLUSIONS:

While FPs follow a precautionary approach to prescribing opioids for CNCP, there are substantial practice and knowledge gaps, with implications for patient safety and costs.

Keywords: Chronic noncancer pain, Guidelines, Opioids, Pain management, Primary care surveys

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

En mai 2010, de nouvelles lignes directrices canadiennes sur la prescription d’opioïdes pour soigner les douleurs chroniques non cancéreuses (DCNC) ont été publiées. Pour évaluer les changements dans les habitudes de prescription d’opioïdes des médecins de famille (MF), il faut connaître leurs pratiques avant la diffusion généralisée de ces lignes directrices.

OBJECTIFS :

Déterminer les pratiques et les connaissances des MF à l’égard de la prescription d’opioïdes pour soigner les DCNC par rapport aux lignes directrices canadiennes et déterminer les facteurs qui empêchent ou incitent les MF à prescrire des opioïdes pour soigner des DCNC.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont préparé un sondage virtuel et pris contact par voie électronique avec les MF qui traitent des DCNC par l’entremise du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada, des bureaux universitaires de formation médicale continue et des collèges provinciaux de réglementation.

RÉSULTATS :

Les chercheurs ont obtenu un total de 710 réponses. Les MF respectaient une approche prudente à l’égard de la prescription d’opioïdes et respectaient déjà les recommandations des lignes directrices canadiennes en abordant les effets indésirables, en surveillant les comportements aberrants liés au médicament et en conseillant de faire preuve de prudence lors de la conduite. Cependant, les MF mettaient rarement fin au traitement aux opioïdes même s’il était inefficace et ne connaissaient pas la « dose vigilante » d’opioïdes, c’est-à-dire la dose quotidienne à laquelle les patients peuvent avoir besoin d’une réévaluation ou d’une surveillance plus attentive. Plus de 40 % des MF ont répondu correctement à seulement deux des neuf questions de connaissances. Le principal critère d’une prescription optimale d’opioïdes consistait à avoir accès aux antécédents d’utilisation d’opioïdes du patient grâce à un programme de surveillance provincial des ordonnances. Les préoccupations à l’égard d’une accoutumance et d’une mauvaise utilisation constituaient les principaux obstacles à une prescription optimale.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les MF respectent une approche prudente à l’égard de la prescription d’opioïdes pour traiter les DCNC, mais on constate d’importantes lacunes sur le plan de la pratique et des connaissances, ce qui a des répercussions sur la sécurité des patients et sur les coûts.

Chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) is a major health problem, the estimated prevalence of which varies according to methodology and settings. Recent data indicate that 25% of the general adult population (1,2) and 40% of seniors living in institutions (2) are affected by CNCP. Opioids are frequently prescribed to decrease pain and improve function in patients with CNCP (3). While evidence for the long-term efficacy of opioids in treating CNCP is weak, over the past several years, there has been a trend toward increased prescribing of opioids, particularly oxycodone and fentanyl. This trend has occurred in several countries (4–6), including the United States (7) and Canada (8), and has been accompanied by an increase in reported opioid abuse and deaths (8–11).

In 2007, the medical regulatory authorities of all Canadian provinces formed the National Opioid Use Guideline Group (NOUGG). NOUGG developed an evidence-based national ‘Guideline for the Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Noncancer Pain’ that was released in early 2010 (12). The Canadian Guideline provides a consistent, evidence-based approach to managing CNCP patients with opioids. It will be important to assess changes in family physicians’ (FPs) prescribing of opioids for CNCP patients following the release of the guideline. This requires some knowledge of FPs’ practices before the guideline was widely disseminated. However, there are little data on opioid prescribing practices of Canadian FPs, being limited to a total of 219 respondents in three studies (1,13,14). Several Canadian and American surveys have found that approximately 30% of FPs do not prescribe opioids for CNCP (13–15), and that FPs are more cautious with prescribing strong opioids than weak opioids (15,16). Factors affecting the likelihood of prescribing opioids include concerns about misuse, dependence and addiction (1,13,17–19) and, to a lesser extent, concerns about regulatory scrutiny (13,17).

Working in conjunction with the team that developed the Canadian guideline, the present study provides a baseline assessment of opioid prescribing practices before the release of the guideline by surveying FPs across the country. Drawing on the Canadian guideline as the gold standard, the present study examined two main questions: How consistent are FPs’ practices and knowledge in prescribing opioids for CNCP relative to the Canadian guideline; and what factors hinder or enable FPs in their prescribing of opioids for CNCP? While we recognized that FPs did not have access to the guideline, we believed it was likely that some recommendations were already being followed because they were already considered best practices.

METHODS

Questionnaire design

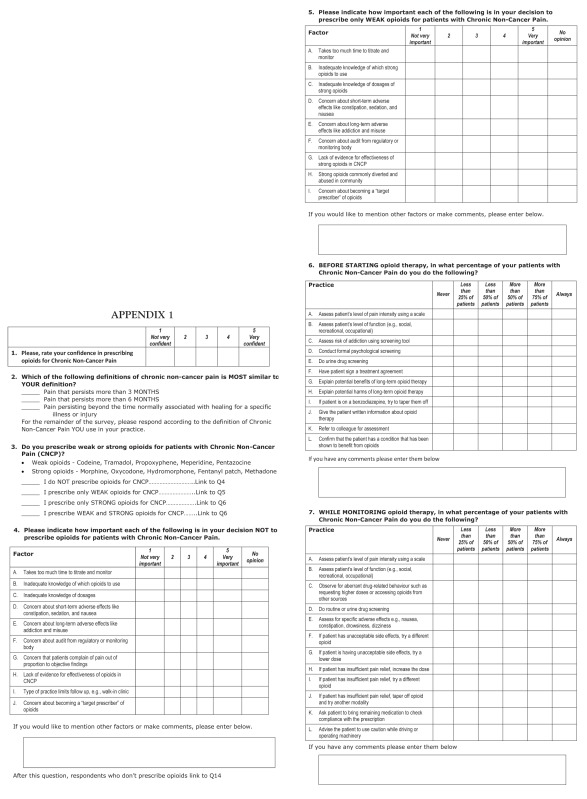

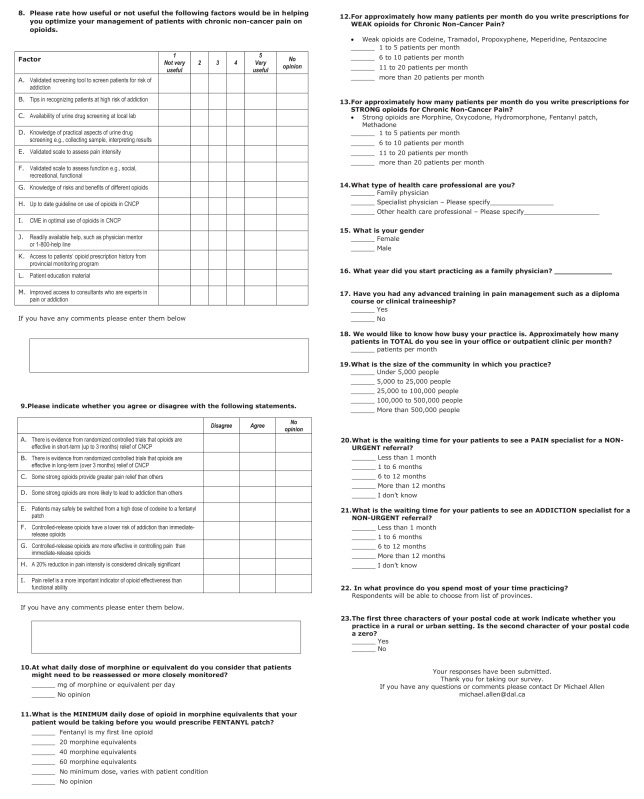

The survey questions were developed with reference to the recommendations of the Canadian Guideline. NOUGG provided access to the guideline recommendations before its release on May 3, 2010, for the sole purpose of designing the survey. The guideline itself was released by posting it on the website of the National Pain Centre at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) (12) and through publication in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (20). Some questions differentiated between weak opioids (codeine, tramadol, pentazocine, propoxyphene and meperidine, with or without acetylsalicylic acid or acetaminophen) and strong opioids (morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl and methadone). The online survey questions were tested for face and content validity by members of NOUGG (n=3), pain specialists (n=2), FPs (n=4) and information technology specialists (n=2). Their comments and suggestions were reviewed by a team consisting of the lead author (MA), an author who was involved in developing the guideline (AF), a pain specialist (PM), a methodologist (MA) and a medical resident (OT). Modifications to the survey were made based on the feedback received. The survey was available in French and English and was accessible from March 30, 2010, to July 10, 2010. The goal was to have the survey accessible before the release of the guideline and it was left open to obtain as many responses as possible. There was no incentive for completing the survey, which is presented in Appendix 1. The Dalhousie University Research Ethics Board (Halifax, Nova Scotia) approved the project.

Data collection

The present cross-sectional descriptive study used Opinio (21), an online survey program hosted at Dalhousie University. The study population included FPs who manage patients with CNCP, who were registered with the College of Family Physicians of Canada and who practiced in any Canadian province. To invite FPs to complete the survey, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the provincial medical regulatory authorities and university continuing professional development offices sent e-mails and electronic newsletters with embedded links to the survey to their FP constituents. There were variations in the number and type of contacts made with FPs (Appendix 2). The invitation and introduction to the survey specified that FPs who do not manage patients with CNCP should not participate. There are approximately 32,000 FPs in Canada (22) but the number that received an invitation to complete the survey is unknown because not all FPs may have received and opened their e-mails or electronic bulletins. Given the lack of a discrete sampling frame and the varied methods of contacting FPs, a nonprobability convenience sample was obtained.

Data analysis

Questions regarding FPs’ practices listed recommended practices and asked respondents how frequently they performed them (never, <25% of patients, <50% of patients, >50% of patients, >75% of patients, always). For these questions, the percentage of respondents performing these practices are reported in three categories: never and <25% of patients; 25% to 50% of patients; and >75% of patients and always.

Questions regarding FPs’ knowledge asked respondents if they agreed, disagreed or had no opinion about various statements. Questions regarding barriers and enablers to prescribing opioids asked respondents to rate the importance of various factors on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not very important, 5 = very important). For each factor, the per cent of response is reported in three categories: 1 and 2 (not important); 3 (neutral); and 4 and 5 (important) on the 5-point scale. Analysis was performed using PASW Statistics version 18.0.2 (IBM Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

Responses

After excluding respondents who were not primary care physicians, 710 responses were received for analysis (701 English and nine French). Responses according to province were: Ontario, n=367; British Columbia, n=79; Nova Scotia, n=71; Saskatchewan, n=30; Alberta, n=26; and Newfoundland and Labrador, n=24. The remaining provinces had <10 responses each and n=85 respondents did not indicate their province of practice.

Three respondents were excluded because they were not primary care physicians (internist, internal medicine resident and oncologist). Family medicine residents (n=2) and FPs with special interests, such as emergency medicine, psychotherapy, palliative care and anesthesia, were included in analysis. It is not possible to determine a precise response rate because this was a convenience sample with no formal sampling frame to draw on. Demographic and practice variables for all FPs are shown in Table 1. Not all respondents answered all questions.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and practice characteristics of respondents

| n (%)* | Total responses, n | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 367 (59) | 622 |

| Have advanced training in pain management | 94 (15) | 627 |

| Years in practice | 621 | |

| 1–5 | 105 (17) | |

| 6–10 | 53 (9) | |

| 11–20 | 111 (18) | |

| 21–30 | 192 (31) | |

| >30 | 160 (26) | |

| Population of practice community | 622 | |

| <5000 | 80 (13) | |

| 5000–25,000 | 138 (22) | |

| >25,000–100,000 | 85 (14) | |

| >100,000–500,000 | 160 (26) | |

| >500,000 | 159 (26) | |

| Patients seen per month | 592 | |

| <200 | 133 (23) | |

| 200–400 | 197 (33) | |

| >400–600 | 173 (29) | |

| >600–800 | 52 (9) | |

| >800 | 37 (6) | |

| Prescriptions for weak opioids written per month | 578 | |

| 1–5 | 178 (31) | |

| 6–10 | 179 (31) | |

| 11–20 | 126 (22) | |

| >20 | 95 (16) | |

| Prescriptions for strong opioids written per month | 548 | |

| 1–5 | 254 (46) | |

| 6–10 | 153 (28) | |

| 11–20 | 78 (14) | |

| >20 | 63 (12) | |

| Confidence prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain | 704 | |

| 1 Not very confident | 23 (3) | |

| 2 | 59 (8) | |

| 3 | 215 (31) | |

| 4 | 303 (43) | |

| 5 Very confident | 104 (15) | |

| Wait time for nonurgent referral to pain specialist, months | 609 | |

| <1 | 16 (3) | |

| 1–6 | 137 (23) | |

| >6–12 | 173 (28) | |

| >12 | 240 (39) | |

| Don’t know | 43 (7) | |

| Wait time for nonurgent referral to addiction specialist, months | 623 | |

| <1 | 45 (7) | |

| 1–6 | 162 (26) | |

| >6–12 | 130 (21) | |

| >12 | 111 (18) | |

| Don’t know | 175 (28) | |

Percentages based on % of respondents who replied to question, not % of total used for analysis (n=710)

Knowledge of opioids

Table 2 shows responses (disagree/agree/no opinion) to knowledge questions, with correct answers in bold. Generally, there were marked knowledge gaps in most responses, with two exceptions. Responses were largely correct concerning randomized controlled trial evidence for short-term effectiveness of opioids in CNCP, and with respect to the restoration of function being a more important indicator of opioid effectiveness than pain relief.

TABLE 2.

Knowledge regarding opioid use in chronic noncancer pain (CNCP)

| Statement |

Frequency of response, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | Agree | No opinion | ||

| There is evidence from RCTs that opioids are effective in short-term (up to three months) relief of CNCP | 8 | 75 | 17 | 603 |

| Some strong opioids provide better pain relief than others | 21 | 71 | 9 | 603 |

| There is evidence from RCTs that opioids are effective in long-term (more than three months) relief of CNCP | 13 | 69 | 17 | 603 |

| A 20% reduction in pain intensity is considered clinically significant | 18 | 65 | 17 | 604 |

| Controlled-release opioids have a lower risk of addiction than immediate-release opioids | 30 | 64 | 6 | 605 |

| Controlled-release opioids are more effective in controlling pain than immediate-release opioids | 27 | 63 | 10 | 602 |

| Some strong opioids are more likely to lead to addiction than others | 28 | 63 | 9 | 603 |

| Patients can be safely switched from a high dose of codeine to a fentanyl patch | 39 | 46 | 16 | 598 |

| Pain relief is a more important indicator of opioid effectiveness than functional ability | 81 | 11 | 9 | 604 |

Correct answers in bold. RCT Randomized controlled trial

Opioid prescribing practices

Eighty-six per cent (n=607) of respondents prescribed both weak and strong opioids. Five per cent (n=32) did not prescribe opioids, 8% (n=58) prescribed only weak opioids and 2% (n=13) prescribed only strong opioids.

Table 3 reviews recommended physician practices before starting a patient on opioids. Twelve practices were listed, two of which were distracters and not included in the guidelines. The three recommended practices most frequently reported were explaining the potential harms and benefits of long-term opioid therapy and assessing patients’ level of function. The two distracters were the practices least frequently performed by FPs.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of following recommended practices performed before starting patients on opioids

| Recommended practice |

Frequency of response, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never, <25%* | 25% to 50%* | >75%, Always* | ||

| Explain potential harms of long-term opioid therapy | 2 | 11 | 87 | 661 |

| Assess patient’s level of function | 4 | 20 | 76 | 671 |

| Explain potential benefits of long-term opioid therapy | 9 | 17 | 75 | 665 |

| Confirm patient has a condition shown to benefit from opioids | 11 | 27 | 62 | 654 |

| Assess patient’s level of pain intensity with scale | 27 | 26 | 47 | 667 |

| If patient is on a benzodiazepine, try to taper them off | 21 | 35 | 44 | 650 |

| Assess risk of addiction using a screening tool | 38 | 25 | 37 | 666 |

| Have patient sign treatment agreement | 42 | 21 | 37 | 665 |

| Give patient written information about opioid therapy | 62 | 23 | 16 | 659 |

| Perform urine drug screen | 68 | 17 | 15 | 667 |

| Refer to colleague for assessment† | 57 | 32 | 11 | 655 |

| Conduct formal psychological assessment† | 71 | 18 | 11 | 668 |

Per cent of respondents indicating they perform practices never or in <25% of their patients, in 25% to 50% of their patients, or in >75% of their patients or always;

Practices not recommended in guideline. Included in survey as distracters to reveal whether respondents tended to report they always performed the listed practices

Table 4 reviews recommended practices while monitoring patients on opioids. As above, the three most frequently reported practices while monitoring patients on opioids all concerned patient safety: observe for aberrant drug-related behaviour; assess for adverse effects; and advise caution while driving or operating machinery. The practices least frequently performed by FPs were urine drug screening and discontinuing opioids because of insufficient pain relief.

TABLE 4.

Frequency of following recommended practices performed while monitoring patients on opioids

| Recommended practice |

Frequency of response, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never, <25%* | 25% to 50%* | >75%, Always* | ||

| Observe for aberrant drug-related behaviour | 2 | 6 | 93 | 651 |

| Assess for adverse effects (eg, nausea, constipation, sedation) | 3 | 13 | 84 | 648 |

| Advise caution while driving or operating machinery | 5 | 14 | 82 | 647 |

| Assess level of function | 4 | 19 | 77 | 652 |

| If patient has unacceptable side effects, try different opioid | 7 | 30 | 63 | 649 |

| If patient has insufficient pain relief, increase dose | 4 | 43 | 53 | 647 |

| If patient has unacceptable side effects, lower dose | 14 | 34 | 53 | 645 |

| Assess level of pain with scale | 28 | 25 | 47 | 652 |

| If patient has insufficient pain relief, try different opioid | 14 | 46 | 40 | 637 |

| Check compliance with pill count | 44 | 29 | 28 | 646 |

| If patient has insufficient pain relief, taper off opioid and try another modality | 26 | 47 | 27 | 643 |

| Perform urine drug screening | 58 | 20 | 22 | 653 |

Per cent of respondents indicating they perform practices never or in <25% of their patients, in 25% to 50% of their patients, or in >75% of their patients or always

The Canadian Guideline introduced the term ‘watchful dose’ of opioids – the daily dose at which patients may need to be reassessed or more closely monitored. Only 5% (n=10) of respondents correctly identified the ‘watchful dose’. Nearly one-half had no opinion (n=147) and 45% (n=143) underestimated the watchful dose of 200 mg morphine equivalent (MEQ) recommended by the guideline. Thirty-eight per cent of respondents (n=211) correctly identified the minimum daily dose of opioid a patient should be taking before receiving the fentanyl patch (60 mg MEQ). Twenty-nine per cent (n=158) indicated that there is no minimum dose and that the amount varies with the patient’s condition, and an additional 14% underestimated the minimum dose.

Barriers to and enabling factors for prescribing opioids

Questions regarding barriers and enablers to prescribing opioids focused on respondents who either did not prescribe opioids for CNCP (n=32) or who prescribed only weak opioids (n=58). The most highly rated reasons for not prescribing opioids and for prescribing only weak opioids were concerns regarding potential long-term adverse events such as addiction and misuse. Concern of strong opioids being diverted and abused in the community was also highly rated. Importantly, concerns regarding regulatory body audits, inadequate knowledge of which opioid to use or the correct doses of opioids were not major barriers (Tables 5 and 6).

TABLE 5.

Rating of factors affecting decision not to prescribe opioids for chronic noncancer pain

| Factor affecting decision |

Rating, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not important* | Neutral* | Important* | ||

| Concern about long-term adverse effects, eg, addiction or misuse | 7 | 7 | 87 | 31 |

| Lack of evidence for effectiveness of opioids in chronic noncancer pain | 16 | 16 | 66 | 32 |

| Concern that patients complain of pain out of proportion to objective findings | 16 | 22 | 63 | 32 |

| Type of practice limits follow-up, eg, walk-in clinic | 43 | 10 | 40 | 30 |

| Concern about becoming a target prescriber of opioids | 34 | 22 | 38 | 32 |

| Concern about audit by regulatory or monitoring body | 56 | 19 | 22 | 32 |

| Concern about short-term adverse effects, eg, constipation, sedation | 47 | 31 | 19 | 32 |

| Takes too much time to titrate and monitor | 66 | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| Inadequate knowledge of dosages | 78 | 13 | 6 | 32 |

| Inadequate knowledge of which opioids to use | 72 | 16 | 6 | 32 |

Per cent of respondents rating importance of factor as 1 or 2 (not important), 3 (neutral), or 4 or 5 (important) on 5-point Likert scale. Percentage may not total 100% because some respondents indicated ‘no opinion’

TABLE 6.

Rating of factors affecting decision not to prescribe strong opioids for chronic noncancer pain

| Factor affecting decision |

Rating, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not important* | Neutral* | Important* | ||

| Concern about long-term adverse effects (eg, addiction or misuse) | 5 | 5 | 88 | 57 |

| Strong opioids are commonly diverted and abused in community | 7 | 7 | 83 | 57 |

| Concern about becoming a target prescriber of opioids | 23 | 12 | 60 | 57 |

| Lack of evidence for effectiveness of strong opioids in chronic noncancer pain | 21 | 21 | 47 | 57 |

| Inadequate knowledge of which strong opioids to use | 42 | 19 | 32 | 57 |

| Concern about audit by regulatory or monitoring body | 47 | 18 | 32 | 57 |

| Concern about short-term adverse effects (eg, constipation, sedation) | 35 | 28 | 32 | 57 |

| Inadequate knowledge of dosages of strong opioids | 55 | 13 | 24 | 55 |

| Takes too much time to titrate and monitor | 63 | 12 | 16 | 57 |

Per cent of respondents rating importance of factor as 1 or 2 (not important), 3 (neutral), or 4 or 5 (important). Percentage may not total 100% because some respondents indicated ‘no opinion’

FPs’ ratings of various factors they identify as being important enablers to optimizing opioid therapy of CNCP were also examined (Table 7). The highest-rated factor was the ability to obtain a patient’s opioid prescribing history from a provincial monitoring program, followed by knowledge of the risks and benefits of different opioids and improved access to pain or addiction specialists. Providing practical tips to help recognize patients at high risk of addiction was also deemed important.

TABLE 7.

Usefulness of enabling factors for optimizing use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain

| Enabling factor |

Rating, %

|

Total responses, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not important* | Neutral* | Important* | ||

| Patients’ opioid prescribing history from provincial monitoring program | 5 | 4 | 87 | 646 |

| Knowledge of risks and benefits of different opioids | 4 | 10 | 84 | 650 |

| Improved access to pain or addiction specialists | 5 | 8 | 84 | 646 |

| Tips in recognizing patients at high risk of addiction | 6 | 11 | 83 | 651 |

| Up to date guideline on use of opioids in chronic noncancer pain | 5 | 11 | 82 | 646 |

| Validated scale to assess function | 8 | 9 | 81 | 650 |

| Continuing medical education in optimal use of opioids in chronic noncancer pain | 7 | 13 | 79 | 643 |

| Patient education material | 7 | 14 | 77 | 647 |

| Validated tool to screen patients for risk of addiction | 12 | 12 | 74 | 652 |

| Validated tool to assess pain intensity | 12 | 12 | 74 | 649 |

| Knowledge of practical aspects of urine drug screening | 13 | 11 | 72 | 649 |

| Availability of urine drug screening at local laboratory | 18 | 15 | 64 | 650 |

| Readily available help such as physician mentor or 1–800 help line | 18 | 16 | 61 | 643 |

Per cent of respondents rating usefulness of factor as 1 or 2 (not useful), 3 (neutral), or 4 or 5 (useful). Percentage may not total 100% because some respondents indicated ‘no opinion’

DISCUSSION

The intent of the present project was not to pass judgement on FPs’ practices in relation to a guideline they had not had a chance to review and assimilate. The intent was to detect areas in which FPs were already following recommendations as part of best practices and areas in which they were not following recommendations as a baseline to detect future practice change as the guideline becomes widely implemented. The results of the present study provide a marker for FP knowledge of opioids before release of the new Canadian guideline; however, given the non-probabilistic nature of the sample, we suggest caution in generalizing to the larger population of FPs.

We observed marked variability in how closely respondents’ practices matched those recommended by the Canadian guideline. Concern for patient safety when prescribing opioids was reflected in FPs’ emphasis on explaining the potential harms of long-term opioid therapy, observing for aberrant drug-related behaviour, assessing adverse effects and advising patient caution while driving. Respondents were also conscientious about assessing function, more so than assessing pain intensity.

The Canadian guideline recommends that long-term opioid treatment be viewed as a therapeutic trial in which physicians and patients define therapeutic goals when starting therapy. If the goals are not reached despite higher doses, it is reasonable to taper patients off the opioids. However, many FPs do not appear to be taking that approach, which is a substantial practice gap. Perhaps physicians are reluctant to discontinue opioids because they mistakenly believe there is long-term randomized controlled trial evidence for the efficacy of opioids in treating CNCP, while in fact the longest trials lasted only 13 weeks (23). Another possibility is that opioids are started by another physician, such as a pain specialist, and respondents are reluctant to make changes.

More concerning, a patient safety issue was identified regarding the minimum daily dose of strong opioids that patients should be taking before prescribing the fentanyl patch. To decrease the potential for overdose from fentanyl, the guideline states that patients should be taking 60 mg to 90 mg MEQ of strong opioid for two weeks (12). Forty-three per cent of respondents believed that there is no minimum dose or that the minimum dose was less than 60 mg MEQ.

Some knowledge gaps identified have cost implications. Most respondents believed some strong opioids provide better pain relief and were more likely to lead to addiction than others. Because there is no consistent evidence to support these differences in efficacy and harms (24), it makes economic sense to start treatment with the least expensive opioid. Similarly, controlled-release preparations are more expensive than immediate-release preparations. While they may be more convenient, there is no conclusive evidence that they offer increased pain relief or decreased potential for addiction (24). Therefore, FPs should feel confident prescribing inexpensive preparations if cost is a concern.

The present study also identified potential enablers and barriers to effective opioid prescribing for CNCP. A number of factors were important to FPs to improve opioid prescribing, particularly being able to obtain patients’ opioid prescribing history from a provincial monitoring program. Also important were support services for FPs, such as access to pain or addiction specialists. Many respondents reported having to wait more than 12 months for a nonurgent referral to a pain specialist. Having access to an up-to-date guideline was also highly rated, which, when combined with low knowledge levels, speaks to the need for improved training and continuing education and support.

Information about barriers to care came from the 90 respondents who did not prescribe opioids or prescribed only weak opioids. For this group of FPs, the main barriers were concern regarding addiction and misuse, diversion for illicit use and being regarded as a target prescriber. These concerns echo those found in other studies on opioid prescribing (1,13,17–19).

To our knowledge, the present study was the first national online survey on opioid prescribing for CNCP that attempted to elicit responses from FPs across Canada. The survey was developed with input from a wide variety of professionals involved in pain management and the development of the Canadian guideline.

A limitation of the present study was that the data were self-reported. However, respondents reported infrequently conducting practices included as distracters, giving credence to the findings. Another limitation was that the number of responses represents a small percentage of the approximately 32,000 FPs in Canada. Other limitations were that we received few French-language responses and the responses varied markedly according to province, likely due to different methods of publicizing the survey. Because the guideline was released online on May 3, 2010 (12), it is possible that some respondents had read it and altered their responses. However, we received only 93 responses after that date and analysis of responses to questions about practices in starting and monitoring opioids received after release of the guideline showed no statistically significant differences compared with responses received before its release. Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences in response to knowledge questions in those who responded before and after the release of the guideline. It is not surprising that publishing the guideline did not affect responses because guideline implementation and adherence is a complex knowledge translation process (25).

Volunteer bias is another potential limitation. Respondents may have had more interest and knowledge of this clinical area than non-responders. Thus, our findings may represent a ‘best-case’ scenario. Demographic and practice responses on this survey were similar to those of the 2007 National Physician Survey, which received responses from approximately 10,000 FPs (26) (data not shown). While this finding does not guarantee the respondents were representative of the entire FP population, it is reassuring.

In contrast to other surveys, which found that 25% to 35% of FPs do not prescribe opioids (13–15,19), we found that only 5% were unwilling to do so. This may be because our survey was directed at FPs who treat CNCP while some other surveys were directed at FPs in general. However, our results are similar to those of unpublished data from the Nova Scotia Prescription Monitoring Program, which found that in 2010, only 8% of FPs did not prescribe opioids for CNCP. Responses to barriers and enablers to care were similar to other surveys. In a survey of Ontario FPs, the most highly rated concern when prescribing opioids was addiction and misuse, the same as we observed. As in other surveys from Canada (13,17) and the United States (18,27), we found that concern regarding audit from a regulatory body was not an important barrier to prescribing opioids. The time required to titrate and monitor opioids was also not reported as a substantial barrier. This may be because FPs recognize the significance of chronic pain and its effects on patients’ lives and are willing to take the time to help their patients if they can. Previous Canadian surveys have found that chronic pain was a significant factor in their practices (16) and that pain management was not overly time consuming (13).

Our study provides a reasonable snapshot of FPs’ current opioid-prescribing practices and knowledge with respect to the new Canadian guideline. It would be informative to repeat the survey with other health care professionals involved in managing CNCP with opioids – pharmacists, pain specialists and nurses – as well as repeating the survey with FPs in two to five years to detect changes since dissemination of the guideline.

CONCLUSIONS

Given that the responses represent only a small sample of Canadian FPs, the present survey identified a number of knowledge and practice gaps that have implications for patient care and the health care system. A reluctance to discontinue opioids if patients are not meeting treatment goals may lead to patients being left on the medications inappropriately and exposed to possible long-term adverse effects. Misunderstandings about increased efficacy and decreased adverse effects with long-acting opioids may lead to increased costs. Unawareness of the hazards of prescribing fentanyl to opioid-naive patients may lead to increased risk of overdose. Despite these gaps, FPs appear to take a precautionary approach to prescribing opioids, advising their patients of possible adverse effects and monitoring them for aberrant drug-related behaviour. The availability of their patients’ opioid prescription history from a monitoring program was highly rated as an enabler to optimal prescribing and not regarded as a barrier to prescribing opioids. Thus, all provinces and territories should consider implementing such a system even though evidence for their effect on prescribing is lacking (28). Finally, FPs identified a current guideline as a valuable resource, an auspicious indicator for uptake of the new Canadian guideline.

APPENDIX 1.

APPENDIX 2. Methods of informing family physicians of survey

| Jurisdiction | Type of contact | Organization | Number of contacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Quarterly print newsletter | CPS of British Columbia | 1 |

| University of British Columbia CME | 1 | ||

| Alberta | E-bulletin | AMA | 2 |

| E-bulletin | University of Calgary CME | 1 | |

| Saskatchewan | CPS of Saskatchewan | 1 | |

| Manitoba | University of Manitoba CME | 2 | |

| Ontario | E-mail notice | CPS of Ontario | 1 |

| Quebec | E-bulletin | CMQ | 1 |

| Print journal | CMQ | 1 | |

| New Brunswick | Print newsletter | CPS of New Brunswick | 1 |

| Prince Edward Island | CPS of Prince Edward Island | 2 | |

| Nova Scotia | CPS of Nova Scotia | 2 | |

| Dalhousie University CME | 1 | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | CPS of Newfoundland and Labrador | 2 | |

| CFPC | E-bulletin | CFPC | 2 |

AMA Albert Medical Association; CFPC College of Family Physicians of Canada; CME Continuing Medical Education Department; CMQ Collège Des Médecins Du Québec; CPS College of Physicians and Surgeons

Footnotes

FUNDING AND ORIGIN OF WORK: This work was performed as an unfunded MSc thesis in Community Health and Epidemiology at Dalhousie University. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest relevant to the present project to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Squire P, Cui E, Horbay GL. Chronic pain in Canada: Have we improved our management of chronic noncancer pain? Pain Res Manag. 2007;12:39–47. doi: 10.1155/2007/762180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada The Daily. < www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/080221/dq080221b-eng.htm> (Accessed June 3, 2012).

- 3.Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, et al. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: An update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) Guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008;11(Suppl 2):S5–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamunen K, Paakkari P, Kalso E. Trends in opioid consumption in the Nordic countries 2002–2006. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:954–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudec R, Tisonova J, Bozekova L, Foltan V. Trends in consumption of opioid analgesics in Slovak Republic during 1998–2002. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:445–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia del Pozo J, Carvajal A, Viloria JM, Velasco A, Garcia del Pozo V. Trends in the consumption of opioid analgesics in Spain. Higher increases as fentanyl replaces morphine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:411–5. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerzan JT, Morden NE, Soumerai S, et al. Trends and geographic variation of opiate medication use in state Medicaid fee-for-service programs, 1996 to 2002. Med Care. 2006;44:1005–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228025.04535.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Sivilotti ML, Kopp A, Qureshi O, Juurlink DN. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. CMAJ. 2009;181:891–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:618–27. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer B, Rehm J, Patra J, Cruz MF. Changes in illicit opioid use across Canada. CMAJ. 2006;175:1385. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer B, Rehm J, Goldman B, Popova S. Non-medical use of prescription opioids and public health in Canada: An urgent call for research and interventions development. Can J Public Health. 2008;99:182–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03405469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-cancer Pain Part B: Recommendations for Practice. National Opioid Use Guideline Group. Apr 30, 2010. < http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/> (Accessed June 3, 2012).

- 13.Morley-Forster PK, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Moulin DE. Attitudes toward opioid use for chronic pain: A Canadian physician survey. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8:189–94. doi: 10.1155/2003/184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nwokeji ED, Rascati KL, Brown CM, Eisenberg A. Influences of attitudes on family physicians’ willingness to prescribe long-acting opioid analgesics for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Clin Ther. 2007;(29 Suppl):2589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potter M, Schafer S, Gonzalez-Mendez E, et al. Opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the UCSF/Stanford Collaborative Research Network. University of California, San Francisco. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scanlon MN, Chugh U. Exploring physicians’ comfort level with opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Pain Res Manag. 2004;9:195–201. doi: 10.1155/2004/290250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenghofer EF, Wilson L, Kahan M, et al. Survey of Ontario primary care physicians’ experiences with opioid prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:324–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turk DC, Brody MC, Okifuji EA. Physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding the long-term prescribing of opioids for non-cancer pain. Pain. 1994;59:201–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchinson K, Moreland AM, de Williams ACC, Weinman J, Horne R. Exploring beliefs and practice of opioid prescribing for persistent non-cancer pain by general practitioners. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlan AD, Reardon R, Weppler C, National Opioid Use Guideline Group Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A new Canadian practice guideline. CMAJ. 2010;182:923–30. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ObjectPlanet Inc Opinio Home Page. < www.objectplanet.com/opinio/> (Accessed June 3, 2012).

- 22.Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies: Survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians-in-training. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1424–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opioids in Chronic Non-cancer Pain 2010. Dalhousie Academic Detailing Service. 2010. < http://cme.medicine.dal.ca/ad_resources.htm> (Accessed June 3, 2012).

- 24.Chou R, Carson S. Drug Class Review on Long-Acting Opioid Analgesics: Final Report Update 5. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Health & Science University; 2008. < www.rx.wa.gov/documents/opioids_final.pdf> (Accessed June 3, 2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis D. Continuing education, guideline implementation, and the emerging transdisciplinary field of knowledge translation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:5–12. doi: 10.1002/chp.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Medical Association, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . National physician survey: 2007 results. Mississauga: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2007. < www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/nps/2007_Survey/2007results-e.asp> (Accessed June 3, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein SM, Laux LF, Thornby JI, et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward pain and the use of opioid analgesics: Results of a survey from the Texas Cancer Pain Initiative. South Med J. 2000;93:479–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer B, Jones W, Murray K, Rehm J. Differences and over-time changes in levels of prescription opioid analgesic dispensing from retail pharmacies in Canada, 2005–2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:1269–77. doi: 10.1002/pds.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]