Abstract

The current research evaluates how perceptions of one’s partner’s drinking problem relate to attempts to regulate partner behavior and relationship functioning, and whether this varies by perceptions of one’s own drinking. New measures are offered for Thinking about your Partner’s Drinking (TPD) and Partner Management Strategies (PMS). Participants included 702 undergraduates who had been in a romantic relationship for at least three months. Participants completed an online survey assessing perceptions of problematic drinking for one’s self and partner, ways in which attempts were made to regulate or restrain their partner’s drinking, relationship outcomes (i.e., satisfaction, commitment, trust, and need fulfillment), and alcohol use and consequences for self and partner. Factor analyses supported a single factor for Thinking about your Partner’s Drinking (TPD) and two factors for the Partner Management Strategies (PMS) scale (i.e., punishment and reward). Results using structural equation modeling indicated that perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem was associated with lower relationship functioning. Further, this association was mediated by strategies using punishment aimed at changing one’s partner’s drinking, but was not mediated by strategies using rewards. Finally, moderation results suggested that this relationship was not as detrimental for participants who perceived they also had an alcohol problem. In sum, perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem was associated with relationship problems through punishing regulation strategies, and was weaker among individuals who also perceived themselves to have a drinking problem.

Keywords: Alcohol, Relationships, Interpersonal Perception

1. Introduction

Alcohol use can have negative effects on romantic relationships, especially if the partner’s drinking is perceived to be problematic. The current research aimed to create measures of perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic (Thinking about your Partner’s Drinking; TPD), as well as strategies intended to reduce the problematic drinking behavior (Partner Management Strategies; PMS). Moreover, considering that perceptions may be more important than actual behavior, this study evaluates the role of perceiving one’s romantic partner’s drinking as problematic on relationship functioning beyond the perceived level of alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences. Further, we examined whether the association between perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic and reduced relationship functioning was due to partner management strategies. Finally, we considered whether the association might vary based upon one’s own perception of a self drinking problem.

1.1 Alcohol and Relationships

The negative association between problematic drinking and relationship outcomes has been well established (e.g., Dawson, Grant, Chou, & Stinson, 2007; Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Leonard & Rothbard, 1999; Marshal, 2003). For example, Fischer et al. (2005) found that those in romantic relationships were more likely to have poorer conversations on days when they drank heavily. Further, heavy drinking days were associated with fewer positive interactions with romantic partners. Additionally, a recent longitudinal study in dating couples found that heavier drinking by either partner within a relationship was associated with negative outcomes the following day. Moreover, feeling disconnected from one’s partner and feeling one’s partner behaved negatively toward them was related to increased alcohol use among women (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). In addition to problem drinking being associated with negative interactions, research has also shown that when primed with thoughts about a recent conflict in a romantic relationship, men who received alcohol felt more negatively about the conflict as compared to men in the placebo or control conditions (MacDonald, Zanna, & Holmes, 2000).

The negative effects of drinking partly depend on concordance (i.e., similarity) of drinking patterns between partners. Several studies suggest that the mutual patterning of drinking (i.e., concordance or discordance of drinking levels between partners) is more important in the association between alcohol use and relationship adjustment than is the level of drinking (i.e., quantity and frequency of drinking) by either partner. Couples with differing drinking patterns reported poorer relationship functioning (Mudar, Leonard, & Soltysinski, 2001; Roberts & Leonard, 1998), and the most adverse consequences of heavy drinking appear to occur when one member drinks heavily and the other does not (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Homish, Leonard, Kozlowski, & Cornelius, 2009; Ostermann, Sloan, & Taylor, 2005). Interestingly, results from Mudar and colleagues (2001) suggested no significant differences in marital satisfaction as a function of level of overall alcohol consumption. Instead, reductions in satisfaction emerged when partners drank in a discordant manner. The existing literature converges to suggest that the integration of alcohol use into the relationship, rather than the alcohol use alone, is an important determinant of relationship functioning over time.

1.2 Interpersonal Perception

Interpersonal perceptions and associations between partners’ perceptions of one another have important implications for individuals comprising a relationship, even beyond their actual reports (Acitelli, Douvan, & Veroff, 1993; Fiske, Lindzey, & Gilbert, 2010). Research has shown positive perceptions of one’s partner to be associated with higher levels of relationship satisfaction and commitment (Cobb, Davila, & Bradbury, 2001; Molden, Lucas, Finkel, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2009; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996; Neff & Karney, 2005; Ruvolo & Fabin, 1999; Watson, Hubbard, & Wiese, 2000). In the perceptions of alcohol use domain, Amato and Rogers (1997) studied the effect of perceptions of drinking in marital relationships and found perceptions of either partner’s drinking as a concern at baseline to be associated with the likelihood of divorce in subsequent years.

Interpersonal perception plays a critical role in the association between alcohol use and relationship outcomes in that the attributions derived from drinking behavior may be perceived as positive (e.g., “We always have a great time when we spend time with friends over happy hour”) or negative (e.g., “Why does s/he always drink so much when we go out?”). If an individual believes his or her partner drinks to have fun and be social and does not drink to a problematic extent, then the behavior may actually be beneficial to the relationship. Research has found that, under conditions of controlled intoxication and controlled conversation topics, alcohol facilitates drinkers to communicate more frequently and to problem-solve more effectively (Frankenstein, Hay, & Nathan, 1985). Alternatively, drinking that is perceived as excessive can become problematic for the self, the partner, and/or the relationship.

The subjective nature of perceptions means that not everyone will perceive the same threshold for what constitutes problematic drinking. As research on concordance has shown, when the discrepancy between the two partners’ drinking is high, conflict and lower relationship functioning is likely. But beyond how much an individual drinks is the level at which an alcohol problem is perceived to be occurring. This may depend on the person’s value system (e.g., religious affiliations vary in their proscriptions regarding alcohol), personal attitudes toward drinking based on previous experience (both one’s own experience and experience with parents and close others), what a normative amount of alcohol use is perceived to be, and myriad other potential factors. Whereas one person may consider three drinks per week a problem, another person’s threshold may lie closer to ten. Importantly, discrepancies in attitudes between partners with regard to alcohol use may have consequences for the level of conflict and distress the couple experiences.

Although research has shown that partners are generally in agreement when estimating more objective indicators of drinking behaviors (e.g., average number of drinks per week; Connors & Maisto, 2003), when the target behavior or emotion is more subjective (e.g., perceived temptation to drink, perceived marital satisfaction), the discrepancy between one’s own rating and one’s partner’s perception increases. For example, married couples with one partner reporting alcohol problems misperceived their partner’s level of relationship satisfaction (Antoine, Christophe, & Nandrino, 2009). Problem drinkers overestimated the marital satisfaction of their partner, whereas spouses underestimated the marital satisfaction of the drinker. Implications of this can be better understood in light of other research that has shown subjective perceptions may be better indicators of satisfaction than actual reports (Fiske et al., 2010; Saffrey, Bartholomew, Scharfe, Henderson, & Koopman, 2003). For example, the perception that one is similar to one’s partner predicted relationship satisfaction better than actual similarity (Acitelli et al., 1993).

1.3 Regulation Attempts by Partners

Close others are usually among the first to try to limit a drinker’s excessive alcohol use (Room, Greenfield, & Weisner, 1991; Wiseman, 1991). In response to recognizing a developing or existing drinking problem, individuals who care about the drinker may engage in management strategies in an attempt to constrain, limit, or control their partner’s drinking. Such attempts may involve behaviors such as complaining or nagging about the drinking, withdrawing from the drinker, and threatening the drinker if the drinking is not controlled (Yoshioka, Thomas, & Ager, 1992). Partner management strategies are consistent with the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed by the drinker (e.g., Holmila, 1985). Not surprisingly, these attempts may actually worsen the situation. Management strategies, particularly ones focused on chastising the drinker, may elicit conflicts between partners, escalating the level of both relationship tension and subsequent alcohol use (Antoine et al., 2009; Yoshioka et al., 1992). The negative effects of these behaviors do not fall solely on the drinker; the partner may also become frustrated or angry about the seemingly wasted effort aimed—many times with good intentions—at reducing a perceived problematic behavior. Further, in cases where the drinker does reduce his or her level of consumption, the partner’s control efforts may interfere with what would be a beneficial outcome if largely aversive behaviors such as yelling or threatening are utilized.

Partner management strategies may take many forms, some of which have a positive focus (e.g., rewarding the partner for non-alcohol oriented activities), and others which are more negatively focused (e.g., punishing the partner for the problematic behavior). Research on general partner regulation behaviors suggests that attempts that are perceived as critical, demanding or punishing may be less effective than attempts that are perceived as genuine or warm (Overall & Fletcher, 2010). With regard to addictive behaviors, positive reinforcement for sobriety yielded lower levels of emotional, psychological, and marital distress, whereas confrontational coping techniques by the partner yielded higher levels of distress (Philpott & Christie, 2008).

1.4 Current Research

Previous research shows that even when controlling for one’s own problematic drinking, one’s partner’s self-reported problematic drinking predicts poorer relationship outcomes (e.g., Cranford, Floyd, Schulenberg, & Zucker, 2011). The foundation for the current research was the idea that perceptions of one’s partner may have important consequences for relationship functioning beyond either partner’s objective reports. The current research evaluated associations between perceptions of a drinking problem (in both one’s self and one’s partner), attempts to regulate one’s partner’s drinking behavior, and relationship functioning. Surprisingly, a measure of perception of partner problematic drinking could not be found and was thus created for this research.

We expected a positive association between how much individuals perceived their partner to drink and perceiving their partner to have a drinking problem (H1a). We also expected a positive association between one’s own reported drinking and perceiving one’s self to have a drinking problem (H1b). We expected a negative association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem and relationship functioning, and we expected this to be true controlling for perceived partner drinking and alcohol-related consequences, own drinking and consequences, and perceiving oneself to have a drinking problem (H2). Further, we expected the negative association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem and relationship outcomes to be mediated by attempts to regulate, control, or constrain the partner’s drinking (H3). Finally, we expected that the negative association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem and relationship functioning to be weaker among individuals who also believe that they themselves have a drinking problem (H4).

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The current research was reviewed and approved by the university Institutional Review Board. Participants included 702 undergraduate students (88.6% female) who had been in a romantic relationship of three months or longer. Participants were, on average, 22.9 years of age (SD = 5.32 years). About a third (34%) of participants identified as Caucasian, 19% African American, 18% Asian, 17% Hispanic/Latino/a, 1% Pacific Islander, 1% Native American, 7% Multi-Ethnic, and 3% Other. With regard to relationship status, 9% of our sample reported casually dating their partner, 54% reported exclusively dating their partner, 17% reported being nearly engaged, 6% reported being engaged, and 13% reported being married to their partner. Thirty percent lived with their partner. Participants completed the survey online in exchange for extra credit after indicating their consent to participate. Participants were asked to complete the survey in a quiet location where they were alone.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Thinking about your partner’s drinking (TPD)

The Thinking about your Partner’s Drinking (TPD) scale was created to assess the perception that one’s partner has a drinking problem (see Appendix A for items). Participants responded to 26 items regarding their feelings about and perceptions of their partner’s alcohol use. Participants indicated their agreement on a 7-point rating scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Reliability (standardized α) was .98.

2.2.2 Thinking about your own drinking (TOD)

The Thinking about your Own Drinking (TOD) scale was created for this study to assess the perception that one has a drinking problem. Participants were asked 25 items regarding their feelings about their own alcohol use. The items were identical to the TPD measure presented above but framed such that the target is the participant rather than the participant’s partner. The item, “I have thought about staging a mini-intervention with our family and friends” was removed as it was not applicable to one’s self. Participants indicated their agreement on a 7-point rating scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Reliability (standardized α) was .97.

2.2.3 Partner management strategies (PMS)

Attempts to change or regulate one’s partner’s drinking were measured with the Partner Management Strategies (PMS) scale, also created for this study (see Appendix B for items). Participants responded to 19 items regarding behaviors aimed at modifying their partner’s alcohol use. Participants indicated how often they engaged in the strategies on a 7-point rating scale (1 = Not at All, 7 = Very Often). Reliability (standardized α) was .93 for Factor 1 and .87 for Factor 2.

2.2.4 Relationship functioning

Functioning was measured with relationship satisfaction, need fulfillment in relationships, commitment, and trust.

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was measured with the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976). The DAS is a commonly used 32-item measure of overall marital adjustment and satisfaction. The regularly accepted cut-off for relationship distress is a total score of less than 100 (Marshal, 2003). Reliability (standardized ∝) in the current sample was .85.

Need fulfillment

Need satisfaction in relationships was measured with the Need Satisfaction in Relationships scale (NSR; La Guardia, Ryan, Couchman, & Deci, 2000). This measure assesses relationship satisfaction in terms of three fundamental psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness), and has been shown to predict a wide range of indicators of relationship quality (Patrick, Knee, Canevello, & Lonsbary, 2007). Nine items measured the extent to which psychological needs were satisfied by one’s partner. Participants indicated their agreement on a rating scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). Research has employed need fulfillment as a single aggregated construct (Deci, Ryan, Gagné, Leone, Usunov, & Kornazheva, 2001) that functions as an overall index of need satisfaction (∝ = .88).

Commitment

Relationship commitment was measured with the commitment subscale of the Investment Model Scale (IMS; Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998). The IMS consists of seven items measuring the extent to which individuals report being committed to their romantic relationships (e.g., “I am committed to maintaining my relationship with my partner,” “I want our relationship to last forever”). Individuals responded to the items on a 9-point rating scale (0 = Do Not Agree at All, 8 = Agree Completely), with higher scores indicating greater commitment (∝ = .88).

Trust

Trust in one’s relationship partner was measured using the Trust in Interpersonal Relationships scale (Rempel, Zanna, & Holmes, 1985). This 17-item measure examines the extent to which an individual feels trust towards his/her partner. Example items include “My partner is very unpredictable. I never know how he/she is going to act from one day to the next,” “I have found that my partner is unusually dependable, especially when it comes to things which are important to me,” and “I can rely on my partner to react in a positive way when I expose my weaknesses to him/her.” Statements were rated on a 7-point rating scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree) with higher scores indicating more trust in one’s partner (∝ = .89).

2.2.5 Drinks per week

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to assess alcohol consumption. Participants were asked, “Consider a typical week during the last three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants responded by reporting the typical number of drinks consumed on each day of the week. Weekly drinking was calculated by summing participants’ responses for each day of the week. Participants responded about their own drinking and separately about perceived partner drinking.

2.2.6 Drinking problems

A modified version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed how often 25 alcohol-related problems have occurred over the previous three months. The RAPI was modified to include two additional items (i.e., “drove after having two drinks,” “drove after having four drinks”). Responses were given on a five-point scale (0 = Never; 1 = 1 to 2 times; 2 = 3 to 5 times; 3 = 6 to 10 times; 4 = More than 10 times). Scores were calculated by summing the items. Participants responded regarding their own drinking consequences (α = .97) and separately regarding their partner’s drinking consequences (α = .97).

3. Results

3.1 Overview

Results for the current research first utilized exploratory factor analyses to examine the factor structures of the TPD, TOD, and PMS measures. Second, analyses using structural equation modeling evaluated the association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem and relationship functioning, when controlling for own drinking, perception of own drinking problem, and perceived partner drinking. Third, we examined whether the association between perceiving a drinking problem in one’s partner and reduced relationship functioning may be mediated by partner management strategies. Finally, we explored whether this association was weaker among individuals who perceived themselves to have a drinking problem.

3.2 Exploratory Factor Analyses

One aim of the current research was to create reliable and valid measures of (a) perceptions of problematic drinking (in both one’s partner and in one’s self), and (b) strategies that individuals use in an attempt to modify partner alcohol use. Focus groups helped to construct an initial item pool of suggested items, and these items were refined based on discussion. Exploratory factor analyses using principal components were utilized to examine factor structures for the measures.

3.2.1 Thinking about your partner’s drinking (TPD)

In the first set of analyses, the perception that one’s partner has a drinking problem revealed a Factor 1 eigenvalue of 17.86, accounting for 69% of the variance. The eigenvalue for the next highest factor was 1.40, accounting for 5% of the variance and not comprising a meaningful factor. Thus, one factor was retained (standardized α = .98). All items with factor loadings of .6 or higher were kept (one item was dropped: “I know my partner may drink a lot sometimes, but I don’t think it’s a problem”). No gender differences were found in TPD scores. The items with factor loadings may be found in Appendix A1.

3.2.2 Thinking about one’s own drinking (TOD)

In the second set of analyses, the perception that one has a drinking problem revealed a Factor 1 eigenvalue of 15.53, accounting for 62% of the variance. Factor 2 had an Eigenvalue 1.33, accounting for 5% of the variance. Consistent with the TPD scale, this was also considered one factor (standardized α = .97). All items had factor loadings of .4 or higher. No gender differences in TOD scores were found.

3.2.3 Partner management strategies (PMS)

For the second set of analyses, partner regulation strategies revealed that Factor 1 (eigenvalue = 10.94) accounted for 58% of the variance. The second eigenvalue was 1.47, accounting for 8% of the variance. The two factors appeared to distinguish punishing strategies from positively reinforcing, rewarding strategies and thus both factors were retained. Follow-up analyses specifying two factors revealed six items as cross-loaders (based on the loading for the secondary factor being more than half the item loading for the first factor). Another item, “Drinking along with him/her,” did not load .5 on any factor and was thus removed. After removal of these items, the Factor 1 eigenvalue was 7.03, accounting for 58% of the variance. The Factor 2 eigenvalue was 1.37, accounting for 11% of the variance. No gender differences in punishing or rewarding strategies were found. Using a model comparisons approach, we evaluated whether the two-factor model fit was significantly better than the one-factor model. Because the models are nested, a chi-square difference test was performed to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the two models. Results indicated that the two-factor model was a significantly better fitting model than was the one-factor model, χ2(2) = 717.87, p < .001. Please see Appendix B1 for the final set of items, factor loadings, and percent endorsing each behavior

3.3 Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and tests of gender differences for all study variables. Table 2 presents overall means, standard deviations, ranges, and zero-order correlations for all study variables. Perceiving one’s self to have a problem with alcohol, drinks per week, and negative alcohol-related consequences were negatively associated with indices of relationship functioning (all ps < .001). Perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem was moderately correlated with perceiving one’s self to have a drinking problem (r = .41, p < .001) and with both reward and punishment regulation strategies.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of all study variables by gender

| Variable | Mean(SD): Women | Mean(SD): Men | Gender Difference (t) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of partner drinking problem (TPD) | 1.71 (1.22) | 1.65 (1.05) | −.46 |

| Perception of own drinking problem (TOD) | 1.55 (.78) | 1.69 (.74) | 1.41 |

| Punishment | 1.37 (.88) | 1.37 (.80) | −.02 |

| Reward | 2.02 (1.35) | 1.77 (1.08) | −1.59 |

| DAS | 115.1 (16.63) | 111.2 (17.94) | −1.92 |

| Need fulfillment (NSR) | 5.98 (1.07) | 5.71 (1.12) | −2.06* |

| Trust | 5.32 (1.07) | 5.32 (.96) | −.01 |

| Commitment | 6.70 (1.51) | 6.28 (1.64) | −2.24* |

| Drinks per week (DDQ) | 3.46 (5.14) | 5.12 (6.43) | 2.55* |

| Drinking Consequences (RAPI) | 2.81 (8.40) | 5.49 (9.42) | 2.57* |

| Perceived partner drinks per week (P-DDQ) | 5.91 (8.19) | 3.67 (4.61) | −2.32* |

| Perceived partner drinking consequences (P-RAPI) | 3.81 (9.93) | 4.77 (9.88) | .78 |

Note.

p < .05

Table 2.

Descriptives and correlations among all study variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TPD | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. TOD | .41*** | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Punishment | .77*** | .39*** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Reward | .71*** | .27*** | .70*** | -- | ||||||||

| 5. DAS | −.33*** | −.24*** | −.40*** | −.28*** | -- | |||||||

| 6. NSR | −.31*** | −.29*** | −.38*** | −.25*** | .60*** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Trust | −.33*** | −.24*** | −.35*** | −.29*** | .55*** | .71*** | -- | |||||

| 8. Commitment | −.23*** | −.21*** | −.29*** | −.19*** | .45*** | .65*** | .53*** | -- | ||||

| 9. DDQ | .13*** | .31*** | .13*** | .16*** | −.12** | −.11** | −.12** | −.12** | -- | |||

| 10. RAPI | .29*** | .53*** | .40*** | .27*** | −.24*** | −.31*** | −.26*** | −.26*** | .37*** | -- | ||

| 11. P-DDQ | .46*** | .13** | .38*** | .46*** | −.20*** | −.10** | −.14*** | −.15*** | .46*** | .20*** | -- | |

| 12. P-RAPI | .55*** | .30*** | .61*** | .47*** | −.35*** | −.35*** | −.34*** | −.33*** | .27*** | .63*** | .46*** | -- |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.85 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 2.00 | 114.61 | 5.95 | 5.32 | 6.66 | 3.65 | 3.11 | 5.65 | 3.92 |

| SD | 1.14 | .83 | .87 | 1.32 | 16.82 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.53 | 5.33 | 8.56 | 7.89 | 9.92 |

| Range | 1–6.77 | 1–5.91 | 1–6.25 | 1–7 | 36–150 | 2.22–7 | 1.67–7 | 0.86–8 | 0–47 | 0–89 | 0–66 | 0–100 |

Note. TPD = Perception of Partner Problem (Thinking about Your Partner’s Drinking); TOD = Self-Perception (Thinking about Your Own Drinking); DAS = Relationship Satisfaction (Dyadic Adjustment Scale); NSR = Need Satisfaction in Relationships; DDQ = Alcohol Consumption (Drinks per Week); RAPI = Alcohol-related Consequences (Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index); P-DDQ = Perceived Partner Drinks per Week (DDQ); P-RAPI = Perceived Partner Alcohol-related Consequences (RAPI).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

With regard to convergent validity, as expected, there was a positive association between the perception that one’s partner has a drinking problem and perceived partner drinking (both number of drinks per week and perceived negative alcohol-related consequences; ps < .001). Additionally, perceiving that one has a drinking problem was positively associated with own number of drinks per week and negative alcohol-related consequences (ps < .001). Moreover, when own consumption and own perception of drinking problem were entered into a regression equation predicting own negative alcohol-related consequences, perception of drinking problem predicted consequences beyond consumption, t(653) = 13.55, p < .001.

3.4 Associations between Perceptions and Relationship Outcomes

Relationship functioning was operationalized in the current research as a latent construct with indicators of relationship satisfaction, need fulfillment, commitment and trust. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test all models via the AMOS 20.0 program. Parameters were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation (Schafer and Graham, 2002).

We first wanted to examine whether perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem (TPD) would be associated with relationship outcomes after controlling for perceived partner alcohol consumption and problems, own alcohol consumption and problems, and perceiving one’s self to have a drinking problem (TOD). A corresponding SEM model included a latent relationship functioning variable as the outcome and TPD, TOD, own drinking (drinks per week and consequences) and perceived partner drinking (drinks per week and consequences) as predictors. Overall, the model provided excellent fit, χ2(20) = 41.42; χ2/df = 2.07; NFI = .985; TLI = .978; CFI = .992; RMSEA = .038. As expected, perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem was negatively associated with relationship functioning, β = −.198, p < .001, and this association held when controlling for one’s own drinking, β = −.030, p = .513, one’s own negative alcohol-related consequences, β = −.054, p = .347, the perception that one’s self has a drinking problem, β = −.136, p = .005, and also controlling for perceived partner drinking, β = −.105, p = .036, and perceived partner negative alcohol-related consequences, β = −.277, p <.001. Thus, perceiving that one’s partner has a drinking problem uniquely contributed to poorer relationship outcomes beyond the negative alcohol-related consequences perceived to be experienced by the partner.

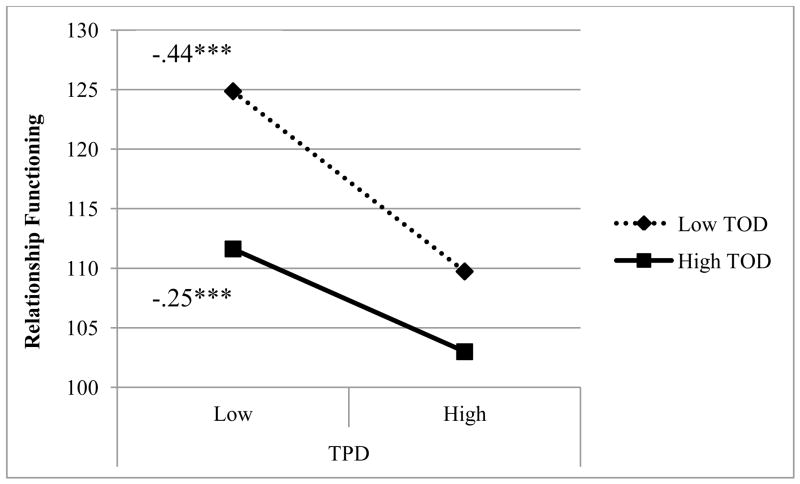

3.5 Mediation by Partner Regulation Strategies

To evaluate the possibility that the association between perceiving a partner drinking problem and reduced relationship functioning was mediated by partner management strategies, an additional model was examined. Paths were specified from perceiving problematic drinking to punishment and reward strategies and from the strategies to relationship functioning. To formally evaluate whether punishment and reward strategies differentially mediated the negative association between perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic and relationship functioning, the ab products approach as described by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon et al., 2002) was employed. Asymmetric confidence intervals for the indirect effects were obtained using the PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon et al., 2007). Estimates for the two paths comprising the mediated effect and their standard errors were entered and distribution of the product confidence limits was computed; confidence intervals (CIs) which do not contain zero are statistically significant. The model as estimated with standardized path estimates and tests of significance may be found in Figure 1. As expected, punishment strategies mediated the association between perceptions of partner drinking as problematic and reduced relationship functioning (CI: −4.154, −2.513). However, reward strategies did not mediate the perception-relationship association (CI: −.619, .777).

Figure 1.

The association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem (TPD) and relationship outcomes is mediated by punishing one’s partner for his or her drinking, but not by rewarding one’s partner for not drinking. Model fit was acceptable, χ2(12) = 37.09; χ2/df = 3.09; NFI = .985; TLI = .976; CFI = .990; RMSEA = .053. The estimates presented are standardized estimates. *** p < .001.

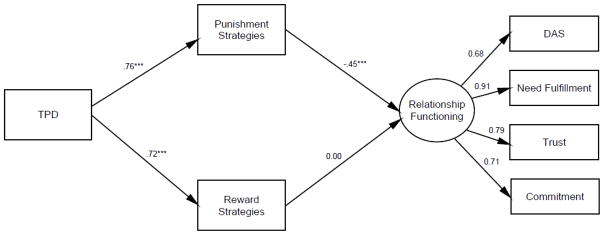

3.6 Moderation by Self Drinking Problems

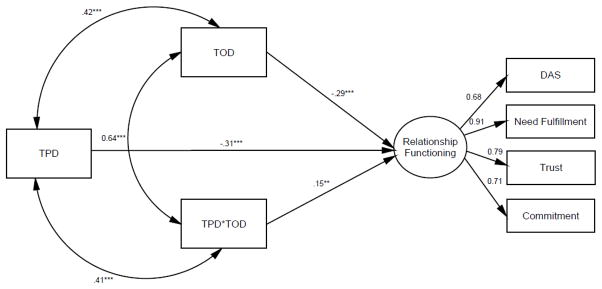

Consistent with research on concordant drinking patterns within a partnership, it is plausible that the association between perception of partner problematic drinking and relationship outcomes may not be as detrimental to the relationship if the individual also perceived him or herself to have a problem. A model was specified in AMOS with relationship functioning as the outcome variable and TPD, TOD, and the two-way product as predictors. As can be seen in Figure 2, the interaction between TPD and TOD was significant, such that the negative effect of TPD was buffered at higher levels of TOD scores. Simple slopes evaluated the association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem and relationship functioning at high and low levels of perceiving oneself to have a drinking problem. After centering predictors around the grand mean, high and low values of partner drinking problems were specified as one standard deviation above and below their respective means in deriving predicted values for the parameter estimates for the figures (Cohen et al., 2003). Tests of simple slopes revealed that perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem was more negatively with relationship functioning among those who perceived themselves as having fewer drinking problems (β = −.44, p < .001) relative to those who perceived themselves to have more drinking problems (β = −.25, p <. 001). This may be seen graphically in Figure 3. This buffering effect did not differ by gender.

Figure 2.

Significant interaction between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem (TPD) and perceiving one’s self to have a drinking problem (TOD) in predicting relationship functioning. Model fit was acceptable, χ2(11) = 31.40; χ2/df = 2.86; NFI = .983; TLI = .971; CFI = .989; RMSEA = .050. Presented estimates are standardized. ** p < .01 *** p < .001.

Figure 3.

Perceiving a drinking problem in the self (TOD) moderates the association between perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem (TPD) and relationship functioning. Please note that range of the relationship functioning latent variable corresponds with the scale of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS), scores of which range from 0–151. *** p < .001

4. Discussion

The present research was designed to consider how perceptions that one’s partner’s drinking is a problem (and how perceptions that one has a drinking problem) influence relationship well-being. Perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic was associated with the level of perceived partner drinking, but it is important to note that these are not necessarily synonymous. There may be considerable variability in what is viewed as problematic from person to person. Moreover, perceiving one’s partner’s drinking to be problematic was uniquely associated with relationship outcomes beyond the perceived amount of partner drinking, beyond one’s own drinking and one’s own alcohol-related consequences, and beyond the perception of problematic drinking in one’s self.

As can be seen in Figure 3, participants who were least happy in their relationships were those who perceived their partner’s drinking and their own drinking to be problematic. This finding may implicate boundary conditions for previous research suggesting that drinking concordance is associated with positive relationship outcomes and that discrepancies in drinking between partners are most predictive of relationship distress. Thus, similar drinking levels between partners may be positively associated with relationship outcomes, but not if both partners are drinking problematically.

The present research also focused on how individuals attempt to deal with a partner who is drinking problematically. Previous research has found that problem drinking by one or both partners in a relationship can create strains on the relationship, impacting trust, satisfaction, and commitment. Moreover, individuals in dissatisfying relationships may use alcohol as a coping mechanism. Specifically, spouses of problem drinkers who cope by using avoidance strategies fare worse on personal and spousal outcomes than those who adopt a more active, problem-focused coping style (Hurcom, Copello, & Orford, 2000). Within the present findings, two general patterns of partner regulation strategies emerged: those designed to punish a partner’s drinking and those designed to reward or reinforce non-drinking. Ironically, strategies designed to punish the partner’s drinking were associated with worse relationship outcomes. More specifically, individuals who perceived their partner’s drinking as problematic were more likely to engage in punishment strategies, which was in turn associated with worse relationship outcomes. In contrast, although perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic was associated with engaging in more reward strategies for not drinking, reward strategies were not, in turn associated with relationship outcomes. It is interesting to note that punishing a partner for problematic drinking does not appear to be an effective strategy, at least with respect to reparative relationship goals. In addition, given that relationship dissatisfaction may motivate more problematic drinking, well-intentioned punishment strategies aimed at motivating or helping the partner may actually exacerbate the problem and make the drinking worse. Relatedly, some of the reward items may only loosely be tied to reward and may instead be tapping into a construct related to constructive criticism or positive communication strategies.

The present findings also highlight the role of perceptions of one’s own drinking in considering perceptions of partner’s drinking as a predictor of relationship outcomes. Results from Rodriguez and colleagues (2013) suggested that perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic was a more consistent predictor of lower relationship functioning than was the partner’s own self-reported drinking. The present research extends this finding, suggesting that perceiving one’s partner’s drinking as problematic is less strongly associated with poor relationship outcomes among those who view their own drinking as problematic. Thus, recognition of one’s own problems with alcohol appears to buffer the effect of perceptions of partner drinking as problematic on relationship outcomes. This may reflect shared causal attributions in considering relationship problems. For example, a problematic drinker may assume that relationship problems are because of “our” drinking problems rather than because of “my own” drinking problems.

It is interesting to note that gender differences did not emerge in partner regulation strategies, in contrast to previous research. For example, Raitasalo and Holmila (2005) found gender differences in attempts regulate their own and their spouse’s drinking behaviors. They found that men felt more pressured to drink less and did not believe frequent alcohol use in small doses was particularly detrimental, whereas the opposite was found for women. These differences may be due to sample discrepancies; in the Raitasalo and Holmila research, participants were older, from a general population sample, and most of them had children. The present sample was younger and consisted of college students. It is possible that gender differences may be less evident among young adults, but emerge with growing commitment over time. Future research is needed to evaluate these questions.

4.1 Limitations and Future Directions

The present research findings should be considered in light of limitations. Two that seem most noteworthy are the preponderance of women in the sample and the absence of partner data. The large sample ensured that there were enough males to draw reasonable conclusions regarding gender differences, but a more even distribution would have been preferable. Additionally, the absence of partner data limited our ability to consider accuracy of impressions about one’s own and one’s partner’s drinking, although some evidence suggests that partners are typically close when estimating consumption (e.g., number of drinks per drinking day; Connors & Maisto, 2003), with the greatest degree of accuracy when the perceiver is a partner or spouse, is in frequent contact with the individual, and is confident about his or her report. Future research may explore the confidence with which individuals perceive their partner’s drinking problem and its relationship with interdyadic accuracy. Of note as well is that the TPD and TOD measures are comprised of many items. Future research may utilize item response theory and measurement models to shorten the measure yet still allow accurate measurement at all levels of the construct.

Among the practical implications suggested by this research is the importance of communication and discussion regarding what each partner views as acceptable and unacceptable with respect to drinking behavior. Importantly, although an individual may not see his or her own behavior as problematic, from the relational perspective, perceptions of problems within the relationship represent actual problems within the relationship, regardless of the objective validity of those perceptions. Raitasalo and Holmila (2005) noted that the association between the drinker’s own concerns and the pressure exerted by the partner may be especially distressing if there is a discrepancy between the drinker and partner’s evaluation. This may occur when an individual believes that his or her own drinking is not an issue, but the partner believes otherwise and attempts to regulate the drinker’s behavior using various strategies.

Regarding clinical implications, current alcohol therapy approaches recognize that both partners’ involvement is more beneficial than that of a singular individual and that treatment is more effective with an additional focus on improving relational functioning (e.g., Epstein & McCrady, 1998; McCrady et al., 1986; McCrady, Stout, Noel, & Abrams, 1991; McCrady & Epstein, 1995; McCrady, Lucas, Finkel, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2009). Research has also shown that similar (i.e., concordant) drinking patterns between partners have been associated with better outcomes than couples whose drinking is discordant (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2007; Homish et al., 2009; Levitt & Cooper, 2010), even among heavy drinkers or those positive for lifetime alcohol dependence (Mudar et al., 2001). Future research would benefit from investigating interactions between own drinking, partner drinking, and perception of problematic partner drinking, as this test would illuminate the effect of partner perceptions in relationships where the partners are concordant in their drinking versus relationships where the drinking pattern is discordant. Another advantageous line of research to explore is whether there is a threshold above which the problematic drinking has become such an issue for both partners individually, that although concordant in pattern between the individuals, reduced relationship functioning is still likely to occur.

Similarly, the TOD measure may also add predictive validity beyond questionnaires measuring consumption and problems, which are framed from a relatively objective perspective and focus primarily on number of drinks, number of times drinking, and number of consequences experienced. These commonly used measures do not collect any kind of information regarding whether the individual believes that the reported quantity and frequency of drinking is problematic for the person. In our research, TOD uniquely predicted poorer relationship functioning beyond self-reported consumption and problems (p = .002). Future research may investigate whether own perception of a problem predicts constructs such as readiness to change beyond consumption and consequences, which would be a useful addition to alcohol interventions focused on motivational change.

Overall, the present findings are consistent with the general agreement in the literature that the association between drinking and relationship outcomes is reciprocal rather than unilateral, and that both drinking and relationship distress can form a feedback loop (Bamford, Barrowclough, & Booth, 2007; Fe Caces, Harford, Williams, & Hannah, 1999; Leonard & Homish, 2008; Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Marshal, 2003). The current findings also suggest that couples interventions would likely benefit from having couples discuss drinking-related values, and what quantity and frequency of alcohol use constitutes problematic drinking. Identifying discrepancies between the drinking patterns and values in the partners and paying particular attention to resolving these differences (e.g., coming to an agreement upon what drinking behavior is acceptable within the relationship) may be crucial to improving the drinking behaviors and relationships of couples in which one or both partners present with drinking problems, relationship problems, or both.

4.2 Conclusion

In conclusion, the present research adds to the existing literature in several ways. New measures are provided to assess constructs that are important for understanding the role of interpersonal perceptions in the association between alcohol use and relationship outcomes. Results provide practical suggestions for partner management strategies (e.g., avoid punishing strategies). Results further underscore the importance of communication between partners regarding acceptable versus unacceptable drinking levels, and reiterate the stronger influence of perceptions of partner behavior over actual behavior in determining relationship outcomes.

Highlights.

A measure for perceiving drinking problems in one’s partner is created.

A measure for regulating partner drinking strategies is created.

Perceived partner drinking problems was associated with poor relationship outcomes.

This association was mediated by punishing one’s partner for drinking.

This was less detrimental among those who thought they had a drinking problem.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant F31AA020442.

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by the NIAAA Grant F31AA020442. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendices

Appendix A.1

Thinking about your Partner’s Drinking (TPD) with factor loadings

Instructions: The following statements refer to your thoughts and feelings about your partner’s drinking. Please indicate your agreement with the following statements by indicating the best response.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Strongly Agree |

| Item | β |

|---|---|

| My partner’s drinking is a source of strain in our relationship | .916 |

| My partner has a lack of control over his or her drinking | .894 |

| I feel less intimate with my partner because of his or her drinking | .881 |

| My partner makes excuses about his or her drinking | .880 |

| My partner and I have arguments about his or her drinking | .876 |

| My partner is hostile when confronted about drinking | .876 |

| My partner is defensive when confronted about drinking | .873 |

| I wish I had more control over how much my partner drinks | .872 |

| I feel like I have to be ready to handle the consequences of my partner’s drinking | .866 |

| I have considered leaving my partner because of his or her drinking | .862 |

| Sometimes my partner scares me with how much he or she drinks | .858 |

| I would be happier if my partner didn’t drink so much | .857 |

| Our relationship would be much better if my partner reduced his or her drinking | .854 |

| I feel like I have to take on additional responsibilities because of my partner’s drinking | .850 |

| I wish my partner wouldn’t drink so many drinks | .849 |

| I wish there was more I could to do make my partner drink less | .845 |

| My partner doesn’t take part in as many activities with me due to his or her drinking | .844 |

| I think my partner has a problem controlling his or her drinking | .821 |

| I think my partner should go to treatment for his or her drinking | .814 |

| My partner’s drinking has interfered with our sex life | .810 |

| I think my partner is an alcoholic | .804 |

| My partner hides his or her alcohol use | .759 |

| I wish my partner wouldn’t drink so often | .744 |

| I have thought about staging a mini-intervention with our family and friends | .705 |

| My partner is a different person when he or she is drunk | .695 |

Appendix B.1

Partner Management Strategies (PMS) with factor loadings

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All | Sometimes | Very Often |

| Item | Respective Factor | Punishment β | Reward β | % Endorsing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threatening to disclose the drinking problem to someone else (like a family member or friend) | P | .909 | −.172 | 9.5 |

| Suggesting he or she go to treatment for his or her drinking | P | .833 | −.093 | 8.8 |

| Yelling about his or her drinking | P | .796 | .112 | 13.8 |

| Threatening to leave | P | .783 | .080 | 14.4 |

| Pouring out drinks | P | .708 | .048 | 12.7 |

| Punishing him or her for drinking | P | .671 | .187 | 15.1 |

| Withholding sex when he or she has had too much to drink | P | .557 | .249 | 18.2 |

| Encouraging him or her to not drink | R | .004 | .835 | 31.1 |

| Praising when he or she does not drink | R | −.047 | .808 | 29.4 |

| Suggesting alternative activities without alcohol | R | .045 | .765 | 27.5 |

| Letting him or her know how much I appreciate the time we spend when he or she is not drinking | R | .028 | .752 | 26.7 |

| Suggesting he or she not drink as much | R | .113 | .725 | 33.2 |

| Criticizing | CL | .336 | .520 | 27.7 |

| Emotional pleading to change | CL | .541 | .398 | 18.2 |

| Expressing my anger at his or her drinking | CL | .610 | .351 | 18.2 |

| Ignoring him or her when drunk | CL | .280 | .516 | 23.7 |

| Rewarding for not drinking | CL | .293 | .488 | 20.7 |

| Nagging | CL | .408 | .472 | 22.5 |

Note. Under respective factor, P = punishment, R = reward, CL = crossloader. % endorsing refers to the percentage of the sample endorsing engaging in the behavior (i.e., endorsing a response other than “not at all”).

Footnotes

Contributors

Author 1 designed the study, collected the data, analyzed the results, and wrote pieces of all major sections. Author 2 wrote pieces of the introduction that summarized previous research studies and compiled the tables. Author 3 participated in analyses and wrote sections of the discussion. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All three authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acitelli LK, Douvan E, Veroff J. Perceptions of conflict in the first year of marriage: How important are similarity and understanding? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Rogers SJ. A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- Antoine P, Christophe V, Nandrino JL. Crossed evaluations of temptation to drink, strain and adjustment in couples with alcohol problems. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:1156–1162. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford Z, Barrowclough C, Booth P. Dissimilar representations of alcohol problems, patient-significant other relationship quality, distress and treatment attendance. Addiction Research and Theory. 2007;15:47–62. doi: 10.1080/16066350601012665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb R, Davila J, Bradbury T. Attachment security and marital satisfaction: The role of positive perceptions and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1131–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. London, England: Psychology Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Maisto SA. Drinking reports from collateral individuals. Addiction. 2003;98:21–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Floyd FJ, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Husbands’ and wives’ alcohol use disorders and marital interactions as longitudinal predictors of marital adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:210–222. doi: 10.1037/a0021349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Chou SP, Stinson FS. The impact of partner alcohol problems on women’s physical and mental health. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:66–75. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM, Gagné M, Leone DR, Usunov J, Kornazheva BP. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:930–942. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, McCrady BS. Behavioral couples treatment of alcohol and drug use disorders: Current status and innovations. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:689–711. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fe Caces M, Harford C, Williams D, Hannah E. Alcohol Consumption and Divorce Rates in the United States. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:647–652. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland B, Lee J, McKnight A, Miller B. Binge drinking in the context of romantic relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1496–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Lindzey G, Gilbert DT. Handbook of social psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Foran H, O’Leary KK. Problem drinking, jealousy, and anger control: Variables predicting physical aggression against a partner. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9136-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenstein W, Hay WM, Nathan PE. Effects of intoxication on alcoholics’ marital communication and problem solving. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1985;46:1–6. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J. Interpersonal relationships and child development. Developmental Review. 1987;7:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kozlowski LT, Cornelius JR. The longitudinal association between multiple substance use discrepancies and marital satisfaction. Addiction. 2009;104:1201–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurcom C, Copello A, Orford J. The family and alcohol: effects of excessive drinking and conceptualizations of spouses over recent decades. Substance Use and Misuse. 2000;35:473–502. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia JG, Ryan RM, Couchman CE, Deci EL. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:367–384. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Homish GG. Predictors of heavy drinking and drinking problems over the first 4 years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:25–35. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Rothbard JC. Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;(Suppl 13):139–146. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Holmes JG. An experimental test of the role of alcohol in relationship conflict. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2000;36:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE. Marital therapy in the treatment of alcohol problems. In: Jacobson N, Gurman A, editors. Clinical handbook of marital therapy, Second edition. NY: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen NK, Hildebrandt T. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:243–256. doi: 10.1037/a0014686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Longabaugh R, Fink E, Stout R, Beattie M, Ruggieri-Authelet A, McNeill D. Cost effectiveness of alcoholism treatment in partial hospital versus inpatient settings after brief inpatient treatment: Twelve month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:708–713. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Stout RL, Noel NE, Abrams DB. Effectiveness of three types of spouse-involved behavioral alcoholism treatment. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1415–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molden DC, Lucas GM, Finkel EJ, Kumashiro M, Rusbult C. Perceived support for promotion-focused and prevention-focused goals: Associations with well-being in unmarried and married couples. Psychological Science. 2009;20:787–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P, Leonard KE, Soltysinski K. Discrepant substance use and marital functioning in newlywed couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:130–134. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationships: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:1155–1180. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. Gender differences in social support: A question of skills or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:79–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Sloan F, Taylor D. Heavy alcohol use and marital dissolution in the USA. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:2304–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJO. Perceiving regulation from intimate partners: Reflected appraisal and self-regulation processes in close relationships. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H, Knee CR, Canevello A, Lonsbary C. The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:434–457. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott H, Christie MM. Coping in male partners of female problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Use. 2008;13:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Raitasalo K, Holmila M. The role of the spouse in regulating one’s drinking. Addiction Research and Theory. 2005;13:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG, Zanna MP. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:95–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LJ, Leonard KE. An empirical typology of drinking partnerships and their relationship to marital functioning and drinking consequences. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:515–526. doi: 10.2307/353866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Greenfield TK, Weisner C. People who might have liked you to drink less: changing responses to drinking by U.S. family members and friends, 1979–1990. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1991;18:573–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CR. The Investment Model Scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:357–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvolo AP, Fabin LA. Two of a kind: Perceptions of own and partner’s attachment characteristics. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:57–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00211.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saffrey C, Bartholomew K, Scharfe E, Henderson AJZ, Koopman R. Self and partner perceptions of interpersonal problems and relationship functioning. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH, Shapiro A, Browne MW. On the multivariate asymptotic distribution of sequential Chi-square statistics. Psychometrika. 1985;50:253–263. doi: 10.1007/BF02294104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Hubbard B, Wiese D. General traits of personality and affectivity as predictors of satisfaction in intimate relationships: Evidence from self- and partner-ratings. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:413–449. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman J. The other half: Wives of alcoholic and their social-psychological situation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka MR, Thomas EJ, Ager RD. Nagging and other drinking control efforts of spouses of uncooperative alcohol abusers: assessment and modification. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1992;4:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(92)90038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]