Abstract

Introduction

Achievement of optimal medication adherence and management of antiretroviral toxicity pose great challenges among Ethiopian patients with HIV/AIDS. There is currently a lack of long-term follow-up studies that identify the barriers to, and facilitators of, adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the Ethiopian setting. Therefore, we aim to investigate the level of adherence to ART and a wide range of potential influencing factors, including adverse drug reactions occurring with ART.

Methods and analysis

We are conducting a 1-year prospective cohort study involving adult patients with HIV/AIDS starting on ART between December 2012 and March 2013. Data are being collected on patients’ appointment dates in the ART clinics. Adherence to ART is being measured using pill count, medication possession ratio and patient's self-report. The primary outcome of the study will be the proportion of patients who are adherent to their ART regimen at 3, 6 and 12 months using pill count. Taking 95% or more of the dispensed ART regimen using pill count at given points of time will be considered the optimal level of adherence in this study. Data will be analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical procedures.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained from the Tasmania Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee and Bahir-Dar University's Ethics Committee. The results of the study will be reported in peer-reviewed scientific journals, conferences and seminar presentations.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will identify factors that affect adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in treatment naïve patients who are initiated on ART with long-term follow-up.

Rates of patient drop out, loss to follow-up and death are high in this setting, which may challenge the success of the project.

Introduction

Ethiopia is home to approximately 800 000 patients with HIV/AIDS and the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the general population is estimated to be 1.5%.1 The free antiretroviral therapy (ART) programme in Ethiopia, introduced in 2005, has decreased mortality and morbidity and improved the quality of life of patients.2 In the past 8 years, decentralisation and scale-up of the HIV care programme has occurred and by the end of 2011, 249 174 adult patients (86% of eligible patients) were on ART.1

Achievement of optimal medication adherence, management of antiretroviral drug-related toxicities and patient retention3 4 are becoming the greatest challenges in the management of HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study of Ethiopian patients reported an adherence rate of 88.1%,5 which is below the near perfect adherence (≥95%) required to maintain the effectiveness of ART.6

Patient retention in HIV care facilities is low, averaged 51–85% in 55 Ethiopian HIV care facilities in a 2-year patient follow-up study.3 Similarly, a 2011 report from the Ethiopian Ministry of Health indicated that patients dropping out from HIV care was a serious issue, with up to 40% of patients who started ART dropping out from treatment in some regions of the country.7 Mortality and drop out from treatment are most common in the first year of patient follow-up in Ethiopia.8

Adherence to medication is a dynamic behaviour affected by factors related to treatment regimen complexity, patient-related variables, patient–healthcare provider relationships and the quality of healthcare services.9 Patient adherence to ART is influenced by regimen-related factors such as pill burden, frequency of dosing, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and fluid and dietary restrictions.10 Similarly, patient-related factors such as lack of transport, shortage of food, use of traditional medicine, alcohol abuse, depression, stigma and discrimination and lack of social support undermine adherence.11–14 Further, a poor patient–healthcare provider relationship and low quality services, such as lack of confidentiality and privacy and drug stock outs can hamper adherence with ART.12

Justification for this study

The sustainable effectiveness of ART depends on patient's ability to adhere with their long-term ART. There is a lack of long-term follow-up studies to identify the various factors altering the medication adherence to ART in Ethiopia. While one prospective study has investigated adherence to ART in Ethiopia15; it was only conducted for 3 months and also did not focus on treatment of naïve patients. A prospective study with a longer follow-up focusing on treatment of naïve patients is required to assess the level of adherence in this patient group and its barriers and facilitators. There is also a need to conduct a prospective study in Ethiopian patients with HIV/AIDS to assess the emergence of ADRs to ART in clinical practice, and the potential relationship between ADRs and non-adherence to ART.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to establish the level of medication adherence and identify factors that influence medication adherence, and assess the incidence of ADRs and associated risk factors in Ethiopian patients with HIV/AIDS initiated on ART.

Methods and analysis

Study design

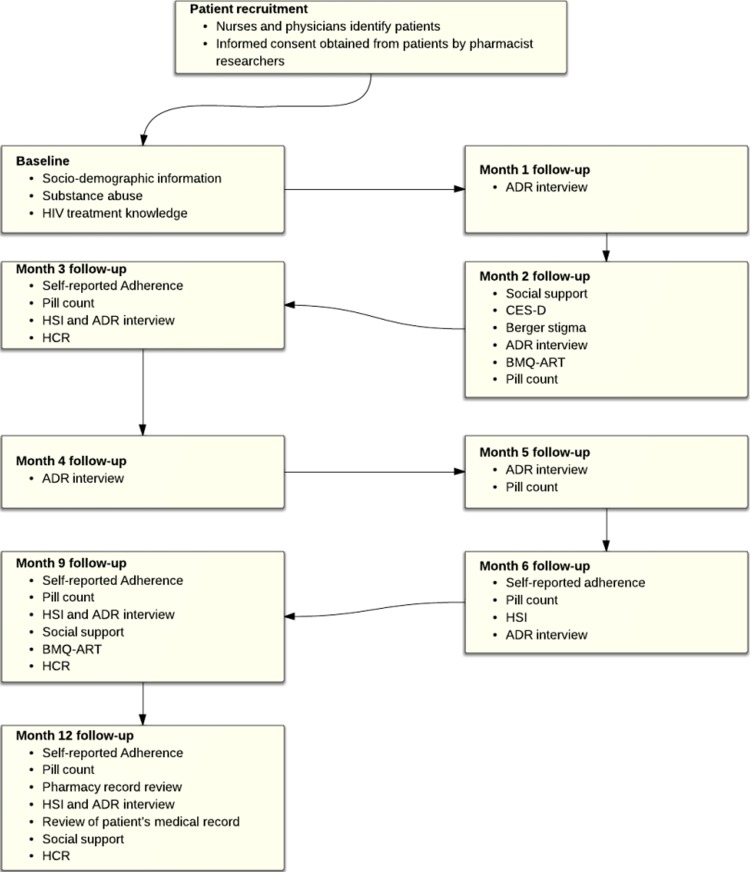

This study is a prospective cohort study in which adult Ethiopian patients with HIV/AIDS initiated on ART are being followed from the time of ART initiation (month (M)=0) to 12 months of therapy (M=12). ART-initiated patients have an appointment every month for 6 months and every 3 months thereafter in ART clinics in Ethiopia; research pharmacists are collecting data on appointment dates. The timeline of data collection activities is structured as shown in figure 1. The data collection points coinciding with the patients’ clinic appointments, not representing additional contact with healthcare providers to minimise the Hawthorne effect on adherence. The sequencing and repeating of measures is to observe the time pattern of different predictors on adherence to ART in treatment naïve patients. Depression, stigma, HIV-treatment knowledge, healthcare relationship and belief about medication and HIV-symptom index may affect adherence in a time-dependent manner and are being measured before and after 6 months of patients’ ART using validated scales. Data regarding the concomitantly administered medications, comorbidities, ADRs and laboratory values are being collected on every appointment date.

Figure 1.

Study design. ADR, adverse drug reaction; BMQ, Belief about Medication Questionnaire; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; HCR, Health Care Relationship; HSI, HIV-Symptom Index.

Study setting

The project is being carried out in two hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia: Gondar University Hospital and Felege-Hiwot Hospital. Each hospital has 400 beds and serves a catchment area of 5 million people. The total number of patients with HIV/AIDS attending each hospital is approximately 7000 and 10 000 at Gondar University Hospital and Felege-Hiwot Hospital, respectively. Recruitment into the study occurred between December 2012 and March 2013. The study will continue to March 2014, which will allow a follow-up period of at least 12 months for each patient.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

All patients with HIV/AIDS at least 18 years initiated on ART for the first time were invited to participate. Patients whose follow-up was to be conducted in outlying areas, rather than at the hospital where ART was initiated, were not included.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was determined based on a previous study, where 76% of patients had optimal dose, time and food adherence to ART.15 Taking a 95% confidence level and precision of 0.07, the sample size was estimated to be 143.

Based on an average of 43 new patients per month, within 4 months of recruitment in each ART clinics the pool of patients for recruitment will be 344. Allowing for a non-participation rate of 23% and loss to follow-up of up to 30% (Mekides B and Desalew K, July 2012, personal communication), the sample size was achievable.

Recruitment

Between December 2012 and March 2013, participants were initially invited by their nurses to participate in this study. At the first visit (usually 2 weeks before ART initiation), nurses gave patients information about the study and invited them to participate. If patients were interested in participating in the study, the research pharmacists contacted them to discuss the research. Informed consent was obtained from volunteer participants using a standard information statement and consent form. Each participant is receiving US$3 to reimburse their time and transport costs. The characteristics of patients who declined participation were collected to determine the representativeness of the sample.

Measures

The questionnaires have been spread to track changes of the different parameters over time as shown in figure 1, while minimising questionnaire fatigue. Assessment of adherence is a problematic issue as there is no gold standard method of measurement.16 In this study self-report, pill count and medication possession ratio (MPR) are being used to measure adherence at months 3, 6, 9 and 12. Use of multiple measures of adherence is recommended in literature as there is no single optimal measure of adherence.16 Adherence to medication found using multiple measures would be converted into ‘percentage dose adherence’ and triangulated. For example, self-reported percentage adherence over 30 days will be triangulated with the percentage of dose adherence obtained using the pill count over the same duration, which will be useful to estimate patients’ true medication adherence. Percentage adherence to each of the medications will be calculated and the lowest dose adherence taken as the adherence for a given patient.

The primary outcome of the study will be the proportion of patients who are adherent to their ART regimen at 3, 6 and 12 months using the pill count. The optimal level of adherence in this study will be considered as taking 95% or more of the dispensed ART regimen using pill count at a point in time. Adherence from pill counts will be calculated by dividing the difference between current and previous pill counts by the number of pills that have to be taken during the same period.5 Pill counts have been found to be an economic and reliable measure of adherence in resource-limited settings.17

A modified AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) self-reported adherence questionnaire that asks patients how many doses they missed in the last 7 days is being used to measure patients’ dose adherence to ART. In addition, two four-item modified questionnaires from the ACTG are being used to measure time and food adherence in the last 7 days.18 Assessing multiple dimensions of adherence by using all items of the ACTG self-reported adherence questionnaires has provided a strong measure of adherence.19 Self-reported adherence is well correlated with viral load suppression and is particularly suitable for resource-limited settings because of its low cost.20

Patients stating they have missed medication will be asked to indicate reasons why from a list of 16 reasons (eg, away from home, busy with other things or simply forgot). Fourteen of the reasons for non-adherence are taken from the ACTG18 and two reasons associated with traditional medicine and religious treatment, respectively, were obtained from literature review.11

Pharmacy refill records are being reviewed and the MPR will be calculated by dividing the total number of days covered with the medication dispensed by the number of days between the first fill and the last refill plus the days’ supply of the last refill.21 This method is suitable in our study as HIV-medication is refilled only from the nearby governmental hospital/health centre pharmacy in Ethiopia.1 Pill count and MPR are superior to self-reported adherence measures and well correlated with virological failure and clinical outcomes.22 Biological surrogate markers such as viral load and CD4 count correlate with medication adherence.23 The CD4 count is measured every 6 months in ART clinics; the measures at months 6 and 12 will be used as a biological surrogate marker of adherence. Viral load is not routinely measured in Ethiopian clinical practice and so has not been included in the trial protocol.

Depression in patients is being evaluated using the seven-item questionnaire of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. This scale has been extensively applied in different settings, including in patients with HIV/AIDS.18 The Revised Berger HIV Stigma Scale has been used for measurement of stigma. The 10 items of the Berger Stigma Scale have been validated in youth who are HIV-positive.24 The Berger Stigma Scale was also used in Kenyan patients with HIV/AIDS.25 A higher score indicates the existence of greater stigma.26

Previous studies have suggested that a lack of social support predisposes patients with HIV/AIDS to medication non-adherence.27 Patients’ satisfaction with the social support they get from family members and friends and the help of the support for remembering their medication is being measured using two four-point scale social support questionnaires.18

The HIV treatment knowledge scale is being used to measure patients’ knowledge on adherence, ADRs and drug resistance. This instrument has been developed and validated by Balfour et al28 in patients with HIV/AIDS taking ART.

The Belief about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) is being used to measure patients’ beliefs about ART. The BMQ consists of two five-item scales probing patients’ beliefs about the necessity of the given medication and their concerns about possible ADRs.29 30

The trust between the patients and healthcare providers is being measured using the 13-item Healthcare Relationship (HCR) trust scale. Items are rated from 0 to 4; the total score ranges from 0 to 52 and a higher score indicates a greater level of trust.31

A self-completed HIV Symptom Index (HSI) is used to measure patients’ concern about 20 possible symptoms associated with ART ADRs. The research pharmacists are interviewing patients, their caregivers and physicians, and referring to patients’ medical records and documenting detailed information regarding the adverse effects that patients experience. The severity of ADRs is being rated using the WHO ADR severity scale.32 Similarly, a physician and a pharmacist have been determining the causality of each ADR using Naranjo's probability scale.33 The reliability between raters and within raters has been improved significantly (p<0.001) with the use of Naranjo's probability scale.33 This Scale has been widely used in various settings.34 In addition, the Schumock and Thornton scale has been used to rate the preventability of adverse drug events.35

Sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables such as age, gender, marital status, religion, level of education, number of children, employment status, disclosure of HIV status, average number of meals per day, monthly income, transportation costs to the clinic and waiting time in the hospital are collected at the baseline.

Laboratory data such as weight, height, history of ADRs, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection status, WHO stage of HIV/AIDS, CD4 count, haematocrit, white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count, platelet count, liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin direct and total), renal function tests (such as blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine and urea) and ART regimen, date of initiation, dose and frequency of treatment, other concomitant medications and comorbidities have been recorded from patients on each appointment date from their medical records using a clinical and laboratory data collection sheet.

‘Drop out’ from ART programme is defined as patients not presenting for refilling of their ART for the past 3 months. Patients’ record are being used to calculate the number of days covered by the last dispensed HIV medication and 90 days will be added to determine the date when patients are categorised as ‘drop outs’. The characteristics of study participants who do not make at least 6 months of follow-up (non-persistent patients) will be examined separately and compared with those who are persistent. Patients lost to the follow-up are being tracked by peer counsellors working in the ART clinics of both hospitals using the registered address and phone number of them or their family member or close friend in their medical record which may help to avoid bias. The reason for being lost to follow-up has been recorded. Sociodemographic and clinical prognostic characteristics of those who are lost from the treatment and those continuing ART will be compared.

The percentage of missing items for each scale will be calculated for each participant. If more than 10% of the items of the scale are missed, the patient's total score on that scale will be excluded from data analysis at that time point. The proportion of missing participants for each variable of interest will be calculated.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive univarate analysis will be conducted for sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables. Adherers will be compared with non-adherers with the Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables and independent samples t tests for normally distributed continuous data. Similarly, the characteristics of patients who developed ADRs and did not develop ADRs will be compared using Pearson's χ2 tests for categorical variables and independent samples t test for continuous variables. Risk factors for adherence will be determined by investigating the influence of sociodemographic, socioeconomic and psychosocial variables, healthcare provider relationship, beliefs about medications and ADRs. Risk factors for ADRs will be determined by investigating the effects of gender, age, body mass index, CD4 count, history of drug allergy, comorbidities, concomitant medications and type of regimen. Multiple variable binary logistic regression will be used to evaluate the independent influence of these risk factors on adherence. The exposure and the potential confounders will be modelled in relation with the outcome variable for adjustment using a multiple-predicative regression model. The final model will be determined after checking multicollinearity. All statistical calculations will be performed using SPSS V.21. A p value of <0.05 will be considered as statistically significant.

Quality control

The English-speaking native researcher made the forward translation of the validated questionnaires into Amharic language. Two physicians working in the ART clinics of the Ethiopian hospitals reviewed the developed Amharic versions. A professional translator made the backward translation to check the difference between the Amharic versions and the original English versions. The differences between the source version and target version were settled by a meeting of the forward translator, a physician and the back translator, and final Amharic versions were developed. The Amharic version was pretested with 40 adult patients receiving ART who would not be included in the main study to check for the reliability and validity of the questionnaires. On average it took about 23 min for the participants to complete the questionnaires at each appointment date. Items found to be problematic by patients were modified.

Data management

The investigators have been checking the collected data for completeness, accuracy and clarity. These checks have been performed daily after data collection and amendments have been made before the next data collection point. Data clean-up and cross-checking have also been performed prior to data analysis. The research pharmacists have been assessing the severity,32 causality33 and preventability35 of adverse events separately using validated algorithms.

The data are being entered from the two study sites in Ethiopia into a custom-built website housed on a secure server at the University of Tasmania. Stored data backed up on a daily basis. Access to the information is only granted to authenticated investigators from anywhere using the Internet.

The custom-built website generates data collection forms for printing. After completion these forms are being scanned and then uploaded to the website. The data from the forms are being entered onto the website by the research pharmacists. A random sample of the scanned forms have been checked against the website data to ensure accuracy. Additionally, the website has a sophisticated series of checks to ensure that fields are entered and that all fields are within expected values. Researchers at each site have been informed of any incomplete or inconsistent data.

Strengths of the study

Several features in the design and planning of the project contribute to the strengths of the study. First, the study is intended to examine predictors of adherence from different perspectives including patient characteristics, medication regimens and the healthcare system. Patients’ socioeconomic status, level of education, belief and knowledge of HIV medication, social support and psychosocial variables are mentioned as predictors of adherence elsewhere.36 37

Second, the study uses multiple measures of adherence, which is recommended in the literature as there is no gold standard method of adherence measurement.16 Although patients in sub-Saharan Africa have been reported to have a comparable rate of adherence with those in the developed countries,38 there is a plausible explanation in the literature that studies in sub-Saharan Africa measure adherence mainly using self-report, which overestimates adherence by as much as 20%.39 Patients refill their HIV-medication in a specific government ART clinic pharmacy; this allows us to use pill count and pharmacy records for adherence measurement.16 40 41

Limitations of this study

Rates of patient drop out, loss to follow-up and death are high in this setting,8 which may challenge the success of the project. The multiple measures of adherence used in the study may alter patients’ behaviour and overestimate medication adherence (ie, Hawthorne effect).42

The study period may not be sufficient to document long-term ADRs, such as endocrine and metabolic adverse events, which may need more than 1 year to become apparent. Patients may not show up in ART clinics for treatment of ADRs or may be treated in other nearby clinics, which may underestimate the incidence of ADRs.

Ethics and dissemination

Nurses working in the ART clinics familiarised patients with the study; research pharmacists delivered further information to interested participants. Participants were given the chance to read and understand the information sheet and to ask any questions before providing written consent. Copies of the information sheet and consent form were handed on to study participants who consented. All personally identifying information has been removed from the questionnaires and study documents. Study participants have been identified only using a unique study number. The data will be stored in a locked filing cabinet in the Bahir Dar University premises for 5 years; afterwards the data will be shredded and disposed of in secure bins. Access to the filing cabinet and custom-built website will only be granted to authenticated investigators. We will disseminate our findings through a public presentation to stakeholders working on HIV/AIDS treatment in Ethiopia. The results of the study will be reported in peer-reviewed scientific journals, conferences and seminar presentations. Our findings will also be openly presented and defended as part of a PhD thesis.

Conclusion

The study is expected to provide extensive information about adherence, including the barriers to, and facilitators of, adherence, and the ADR profile among a cohort of Ethiopian patients starting on ART. This will establish an important foundation for a subsequent intervention study focusing on improving adherence in ART naïve patients with HIV/AIDS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank nurses working in antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinics of both hospitals for their participation in the design of the study. The authors acknowledge Endalkachew Admassie for his contribution during the design of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: WMB, GMP, LC, LB and PG have contributed equally to the design of the study. WMB drafted the manuscript. PG developed the custom-built website. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was financially supported by the Tasmanian School of Pharmacy, University of Tasmania.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Tasmania Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: H0012722) and Bahir-Dar University's Ethics Committee (RCS/567/2004).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office Country progress report in HIV/AIDS response. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reniers G, Araya T, Davey G, et al. Steep declines in population-level AIDS mortality following the introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. AIDS 2009;23:511–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assefa Y, Kiflie A, Tesfaye D, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment program in Ethiopia: retention of patients in care is a major challenge and varies across health facilities. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assefa Y, Damme WV, Mariam DH, et al. Toward universal access to HIV counseling and testing and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: looking beyond HIV testing and ART initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010;24:521–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyene KA, Gedif T, Gebre-Mariam T, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and its determinants in selected hospitals from south and central Ethiopia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:1007–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr A, Cooper DA. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet 2000;356:1423–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assefa Y, Alebachew A, Assefa A, et al. Multi-sectoral HIV/AIDS response monitoring & evaluation report. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wubshet M, Berhane Y, Worku A, et al. High loss to follow-up and early mortality create substantial reduction in patient retention at antiretroviral treatment program in north-west Ethiopia. ISRN AIDS 2012;2012:721720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: from a predictive to a dynamic approach. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:1481–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingersoll KS, Cohen J. The impact of medication regimen factors on adherence to chronic treatment: a review of literature. J Behav Med 2008;31:213–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merten S, Kenter E, McKenzie O, et al. Patient-reported barriers and drivers of adherence to antiretrovirals in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-ethnography. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15(Suppl 1):16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasti SP, van Teijlingen E, Simkhada P, et al. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Asian developing countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbuagbaw L, van der Kop ML, Lester RT, et al. Mobile phone text messages for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a protocol for an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Kop ML, Ojakaa DI, Patel A, et al. The effect of weekly short message service communication on patient retention in care in the first year after HIV diagnosis: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (WelTel Retain). BMJ Open 2013;3:e003155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, et al. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2008;8:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson DL, Potoski B, Capitano B. Measurement of adherence to antiretroviral medications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;31(Suppl 3):103–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Charlebois ED, et al. Multiple validated measures of adherence indicate high levels of adherence to generic HIV antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;36:1100–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). AIDS Care 2000;12:255–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds NR, Sun J, Nagaraja HN, et al. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: a cross-protocol analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:402–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, et al. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav 2006;10:227–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:449–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon JH, Jordan MR, Kelley K, et al. Pharmacy adherence measures to assess adherence to antiretroviral therapy: review of the literature and implications for treatment monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:493–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill CJ, Hamer DH, Simon JL, et al. No room for complacency about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2005;19:1243–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, et al. Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:96–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarna A, Luchters S, Geibel S, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy of modified directly observed antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:611–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health 2001;24:518–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vowles KE, Thompson M. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balfour L, Kowal J, Tasca GA, et al. Development and psychometric validation of the HIV Treatment Knowledge Scale. AIDS Care 2007;19:1141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horne R, Buick D, Fisher M, et al. Doubts about necessity and concerns about adverse effects: identifying the types of beliefs that are associated with non-adherence to HAART. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bova C, Route PS, Fennie K, et al. Measuring patient-provider trust in a primary care population: refinement of the health care relationship trust scale. Res Nurs Health 2012;35:397–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO Monitoring and reporting adverse events. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm 1992;27:538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia EA, Pliatsika PA, et al. Socioeconomic status (SES) as a determinant of adherence to treatment in HIV infected patients: a systematic review of the literature. Retrovirology 2008;5:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, et al. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e38443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;296:679–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner G, Miller LG. Is the influence of social desirability on patients’ self-reported adherence overrated? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;35:203–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller LG, Hays RD. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral medications in clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials 2000;1:36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berg KM, Arnsten JH. Practical and conceptual challenges in measuring antiretroviral adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43(Suppl 1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haberer JE, Kiwanuka J, Nansera D, et al. Multiple measures reveal antiretroviral adherence successes and challenges in HIV-infected Ugandan children. PloS ONE 2012;7:e36737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.