Abstract

The present study is aimed to investigate antioxidant activity of the extracts of Cassia fistula Linn. (Leguminosae) fruit pulp. Cassia fistula Linn., a Indian Laburnum, is widely cultivated in various countries and different continents including Asia, Mauritius, South Africa, Mexico, China, West Indies, East Africa and Brazil as an ornamental tree for its beautiful bunches of yellow flowers and also used in traditional medicine for several indications. The primary phytochemical study and in vitro antioxidant study was performed on hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp. Phytochemical screening of the plant has shown the presence of phenolic compounds, fatty acids, flavonoids, tannins and glycosides. Phenolic content was measured using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and was calculated as gallic acid equivalents. Antiradical activity of hydro alcoholic extract was measured by DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl) assay and was compared to ascorbic acid. Ferric reducing power of the extract was also evaluated by Oyaizu method. In the present study, three methods were used for evaluation of antioxidant activity. First two methods were for direct measurement of radical scavenging activity and third method to evaluate the reducing power. Results indicate that hydro alcoholic fruit pulp extracts have marked amount of total phenols which could be responsible for the antioxidant activity. These in vitro assays indicate that this plant extract is a significant source of natural antioxidant, Cassia fistula fruit pulp extract shows lower activity in DPPH and total phenol content as compared with standard which might be helpful in preventing the progress of various oxidative stresses.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Aragwadha, Cassia fistula, free radical, phenols

Introduction

Natural antioxidants present in the plants scavenge harmful free radicals from our body. Free radicals are any species capable of independent existence that contains one or more unpaired electrons which react with other molecule by taking or giving electrons, and involved in many pathological conditions,[1] and they play very important role in human health and beneficial in combating against several diseases like cardiovascular disorders, lung damage, inflammation etc. These free radicals are highly unstable and when the amount of these free radicals exceed in the body, it can damage the cells and tissues and may involve in several diseases. Thus, there is a need of antioxidants of natural origin because they can protect the human body from the diseases caused by free radicals.[2,3]

An antioxidant is a molecule capable of slowing or preventing the oxidation of other molecules. The most common reactive oxygen species (ROS) include superoxide (O2−) anion, hydrogen peroxide (H2 O2), peroxyl (ROO−) radicals, and reactive hydroxyl (OH−) radicals. The nitrogen-derived free radicals are nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite anion (ONOO).[4] Under normal state of affairs, the ROS generated are detoxified by the antioxidants nearby in the body and there is symmetry between the ROS generated and the antioxidant present. However, due to ROS over production and/or derisory antioxidant argument, this equilibrium is hindered favoring the ROS gain that culminates in oxidative hassle. The ROS readily attack and induce oxidative damage to various biomolecules including proteins, lipids, lipoproteins and DNA.[5] This oxidative damage is decisive etiological factor concerned in quite a lot of chronic human diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, atherosclerosis, arthritis, and neurodegenerative diseases and also in the ageing course.[6] Based on growing interest in free radical biology and the lack of effective therapies for most chronic diseases, the expediency of antioxidants in protection against these diseases is defensible. Epidemiological studies have shown that the intake of antioxidants such as vitamin C reduces the risk of coronary heart diseases and cancer.[7] It is possible to reduce the risk of chronic diseases and prevent disease progression by either enhancing the body's natural antioxidant defenses or by supplementing with proven dietary antioxidants.[8]

Currently available synthetic antioxidants like BHT, butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA) and tertiary butylated hydroquinones have been suspected to cause or prompt negative health effects. Hence, strong restrictions have been placed on their application and there is a trend to substitute them with naturally occurring antioxidants.[9] Several studies revealed that phenols, mainly the type of flavonoids, from some medicinal plants are safe and bioactive, and have antioxidant properties and exert anticarcinogenic, antimutagenic, antitumoral, antibacterial, antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects.[10] Therefore in current years, substantial attention has been directed towards credentials of plants with antioxidant ability that may be used for human expenditure.

Due to their redox properties, they act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, singlet oxygen quenchers and chelating metals.[11,12,13] The medicinal properties of plants have been investigated in the recent scientific developments throughout the world, due to their potent antioxidant activities, no side effects and economic viability.[14] One of the areas, which attracted a great treaty of attention in recent years is antioxidant in the control of degenerative disease in which oxidative dent has been implicated. Several plant extracts have shown antioxidant activity.[15,16,17]

Materials and Methods

Collection of plant materials

The ripe pods of Cassia fistula were collected from the local gardening area located in Jamnagar, Gujarat, India in the month of June-Aug 2009. The plant was authenticated in the Pharmacognosy laboratory, I.P.G.T. and R.A. Jamnagar, Gujarat, India. Each specimen was labeled, numbered, annotated with date and place of collection.

Preparation of plant extract

Extraction of Cassia fistula fruit pulp was carried out using known standard procedures.[18] The fresh pulp of C. fistula pods (25.0 g) was extracted with 900 ml of diluted methanol in a Soxhlet apparatus. The extract were then combined, filtered and evaporated to dryness on a hot water bath to yield a Soxhlet crude extract (9.7 g).

The extract were kept in sterile bottles, under refrigerated conditions, until further use. They were used directly for DPPH assay, total phenol and ferrus-reducing power content and also for assessment of antioxidant capacity.

Preliminary phytochemical testing

The extract were subjected to preliminary phytochemical testing to detect for the presence of different chemical groups of compounds. Air-dried and powdered plant materials were screened for the presence of saponins, tannins, alkaloids, flavonoids, triterpenoids, steroids, glycosides, anthraquinones, cumarin, saponins, gum, mucilage, carbohydrates, reducing sugars, starch, protein and amino acids as described in literatures.[19,20,21]

Chemicals and Instruments

Chemicals

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Lancaster-UK), gallic acid (Loba-India) were purchased from Krishna scientific traders, Rajkot, Gujarat, India. Folin Ciocalteu's reagent, sodium carbonate, ascorbic acid, hydrogen peroxide, potassium ferricynide, trichloroacetic acid, ferric chloride, and all other reagents of analytical grade were obtained from the pharmaceutical chemistry laboratory, I.P.G.T and R.A., Jamnagar, Gujarat, India.

Instruments

UV spectrophotometer (Systronic double beam-UV-2201).

Centrifuge machine (Remi instruments-C24).

Determination of total antioxidant activity

In-vitro antioxidant activity

Free radical scavenging activity (DPPH assay)

The anti-oxidant potential of any compound can be determined on the basis of its scavenging activity of the stable 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical as described by Sadhu et al.[23] DPPH is a stable free radical containing an odd electron in its structure and usually utilized for detection of the radical scavenging activity in chemical analysis.

The absorption maximum of a stable DPPH radical in methanol was at 517 nm. The decrease in absorbance of DPPH radical is caused by antioxidants, because of the reaction between antioxidant molecules and radical progresses, which results in the scavenging of the radical by hydrogen donation.

Preparation of standard solution

Required quantity of ascorbic acid was dissolved in methanol to give the concentration of 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 and 60 μg/ml.

Preparation of test sample

Stock solutions of samples were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of dried hydro alcoholic extract in 10 ml of methanol to give a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Then prepared sample concentrations of 10, 15, 25, 50 and 60 μg/ml.

Preparation of DPPH solution

3.9 mg of DPPH was dissolved in 3.0 ml methanol; it was protected from light by covering the test tubes with aluminum foil.

Protocol for estimation of DPPH scavenging activity

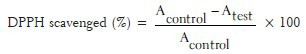

Antiradical activity was measured by a decrease in absorbance at 517 nm of a solution of colored DPPH in methanol brought about by the sample.[23,24,25,26] A stock solution of DPPH (1.3 mg/ml in methanol) was prepared such that 75 μl of it in 3 ml methanol gave an initial absorbance of 0.9. Decrease in the absorbance in the presence of sample extract and standard at different concentrations was noted after 30 min. EC50 was calculated from % inhibition. A blank reading was taken using methanol instead of sample extract. Absorbance at 517 nm is determined after 30 min using UV spectrometer (Systronic double beam- UV-2201). Lower absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates higher free radical scavenging activity. The EC50 value was calculated graphically. The capability to scavenge the DPPH radical was calculated using the following equation.

Where, Acontrol is the absorbance of the control reaction and Atest is the absorbance in the presence of the sample of the extracts.

Reducing power assay

For the measurement of the reductive ability, we investigated the Fe3+ Fe2+ transformations in the presence of Cassia fistula hydro alcoholic extract following the standard method.[27] The reducing capacity of a compound may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity. Like the antioxidant activity, the reducing power of Cassia fistula hydro alcoholic extract increases with increasing concentration.

Preparation of standard solution

3 mg of ascorbic acid was dissolved in 3 ml of distilled water. Dilutions of this solution with distilled water were prepared to give the concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μg/ml.

Preparation of test sample

Stock solutions of samples were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of dried hydro alcoholic extract in 10 ml of methanol to give a concentration of 1mg/ml. Then sample concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μg/ml were prepared.

Protocol for reducing power

According to this method, the aliquots of various concentrations of the standard and test sample extracts (10 to 100 μg/ml) in 1.0 ml of deionized water were mixed with 2.5 ml of (pH 6.6) phosphate buffer and 2.5 ml of (1%) potassium ferricyanide. The mixture was incubated at 50°C in water bath for 20 min after cooling. Aliquots of 2.5 ml of (10%) trichloroacetic acid were added to the mixture, which was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The upper layer of solution 2.5 ml was mixed with 2.5 ml distilled water and a freshly prepared 0.5 ml of (0.1%) ferric chloride solution. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm in UV spectrometer (Systronic double beam-UV-2201).[28] A blank was prepared without adding extract. Ascorbic acid at various concentrations (10 to 100 μg/ml) was used as standard. As illustrated in figures, Fe3+ was transformed to Fe2+ in the presence of Cassia fistula extracts. This result indicates that increase in absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates increase in reducing power.

Total phenolic content

Preparation of standard solution

3 mg of gallic acid was dissolved in 3 ml of distilled water. Dilutions of this solution with distilled water were prepared to give the concentrations of 25, 50, 75, 100, 200 and 250 μg/ml.

Preparation of test sample

Stock solutions of samples were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of dried hydro alcoholic extract in 10 ml of methanol to give a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Then sample concentrations of 25, 50, 75, 100, 200 and 250 μg/ml were prepared.

Protocol for total phenolic content

Total phenolic content was determined using Folin-Ciocalteu was established by following standard methods.[29] The powdered extracts of plant were dissolved in methanol to obtain a concentration of 10 mg/10 ml. From this solution, 1 ml was taken and gave dilution up to 10 ml (100 μg/ml of stock solution) with the same solvent. It was considered as the stock solution. From this stock solution, different concentrations 25 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 75 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, 200 μg/ml, were made following the same procedures for standard. Gallic acid was used as the standard. 1.0 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added in these concentrations samples and the content of the flask was mixed thoroughly. The mixture was then kept for 5 min and to it 4 ml of 20% w/v sodium carbonate solution was added, the volume was made with double distilled water. The mixture was kept for 30 min until blue color develops. The absorbance of blue color developed which was recorded at 765 nm in UV spectrophotometer. The % of total phenolic was calculated from the calibration curve of gallic acid plotted by using the similar procedure.[30,31]

Results and Discussion

Preliminary phytochemical screening

It was found that hydro alcoholic extract of Cassia fistula contained saponins, steroids, triterpenodis, and higher amount of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, tannins, glycosides, anthraquinones, gums, mucilage and amino acids.

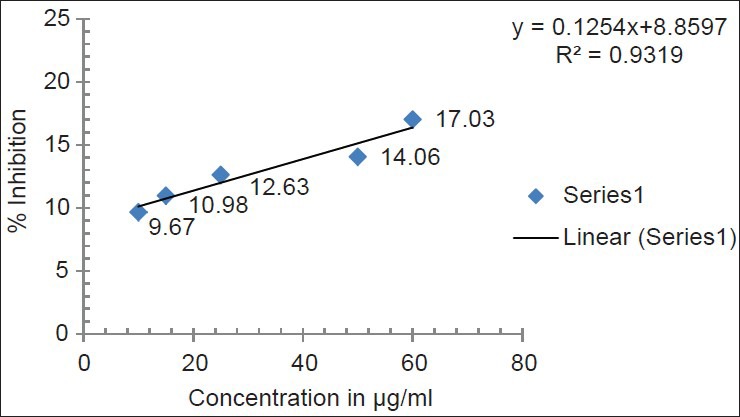

DPPH free radical scavenging activity

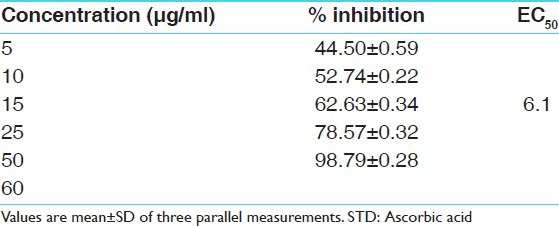

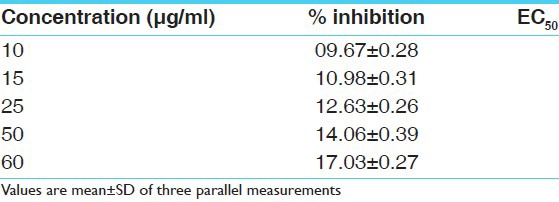

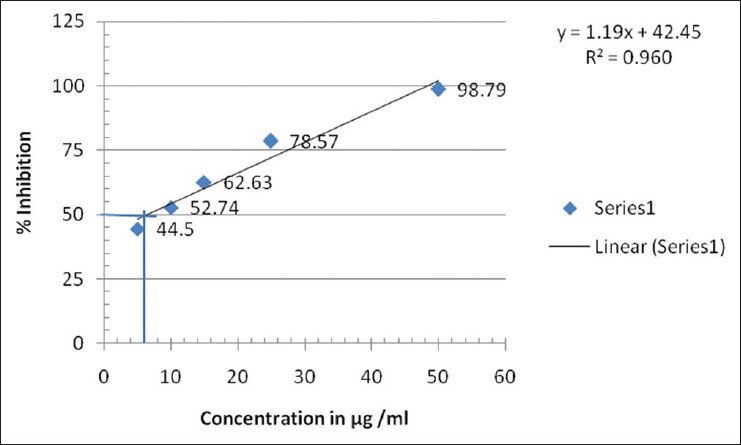

DPPH is a stable free radical at room temperature and accepts an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule. The reduction capability of DPPH radical was determined by the decrease in its absorbance at 517 nm, which is induced by different antioxidants. The decrease in absorbance of DPPH radical caused by antioxidants, because of the reaction between antioxidant molecules and radical progress, results in the scavenging of the radical by hydrogen donation. Cassia fistula exhibited a comparable antioxidant activity with that of standard ascorbic acid at varying concentrations tested (5, 10, 15, 25, 50, 60 μg/ml). There was a dose dependant increase in the percentage antioxidant activity for all concentrations tested [Tables 1 and 2]. The extract at a concentration of 10 μg/ml showed a percentage inhibition of 9.67 ± 0.28 and for 60 μg/ml it was 17.03 ± 0.27. Ascorbic acid was used as the standard drug for the determination of the antioxidant activity by DPPH method. The concentration of ascorbic acid varied from 1 to 50 μg/ml. Ascorbic acid at a concentration of 5 μg/ml exhibited a percentage inhibition of 44.50 ± 0.59 and for 50 μg/ml 98.79 ± 0.28 [Tables 1 and 2]. A graded increase in percentage of inhibition was observed for the increase in the concentration of ascorbic acid. The EC50 value of ascorbic acid was found to be 6.1 μg/ml. EC50 value of sample extracts could not be calculated because of lower values of inhibition than 50%. All determinations were done in triplicates and the mean values were determined [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Percentage inhibition of standard at various concentrations (μg/ml) in hydrogen peroxide scavenging model

Table 2.

Percentage inhibition of hydro alcoholic extracts of fruit pulp at various concentrations (μg/ml) in hydrogen peroxide scavenging model

Figure 1.

DPPH free radical scavenging activity of standard ascorbic acid

Figure 2.

DPPH free radical scavenging activity of hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp

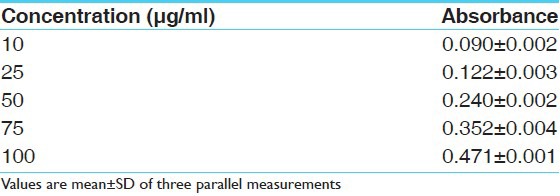

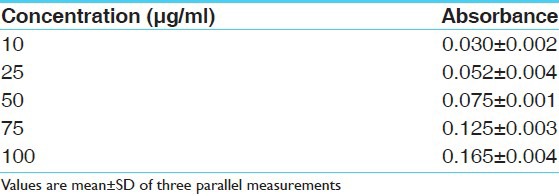

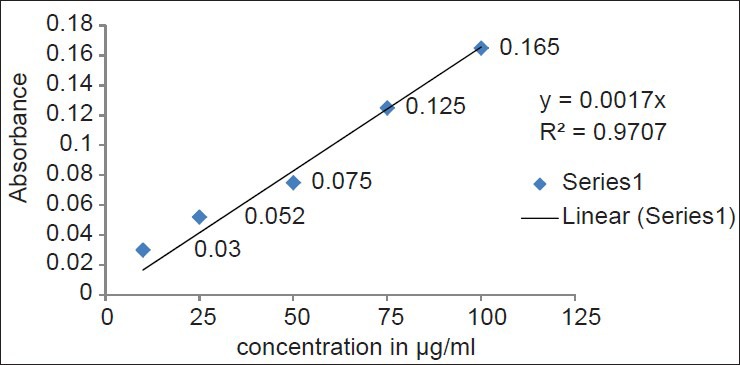

Reducing power assay

Reducing power assay method is based on the principle that substances, which have reduction potential, react with potassium ferricyanide (Fe3+) to form potassium ferrocyanide (Fe2+), which then reacts with ferric chloride to form ferric–ferrous complex that has an absorption maximum at 700 nm. The reducing power of the hydro alcoholic extracts and standard increases with the increase in amount of sample and standard concentrations [Tables 3 and 4]. The reducing power shows good linear relation in both standard (R2 = 0.981) and sample extract (R2 = 0.970) [Figures 3 and 4].

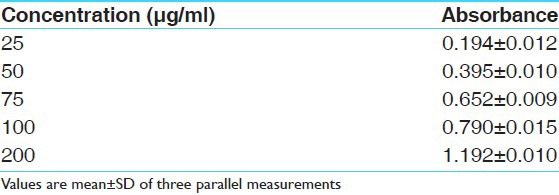

Table 3.

Absorbance of standard at various concentrations (μg/ml) in ferric reducing power determination model

Table 4.

Absorbance of hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp at various concentrations (μg/ml) in ferric reducing power determination model

Figure 3.

Ferric reducing power determination of standard ascorbic acid

Figure 4.

Ferric reducing power determination of hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp

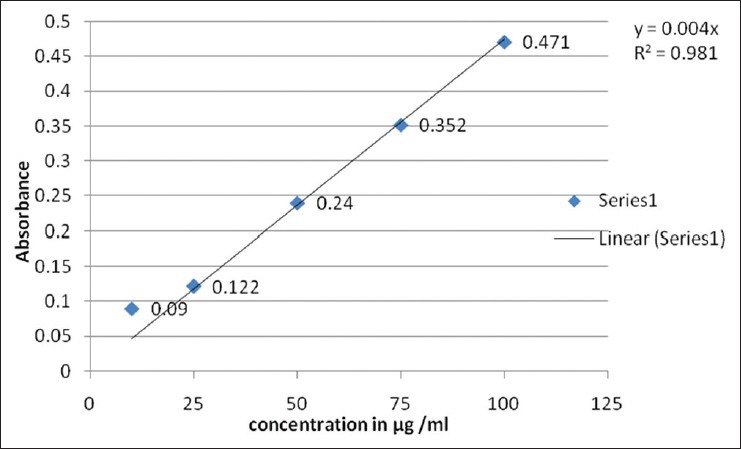

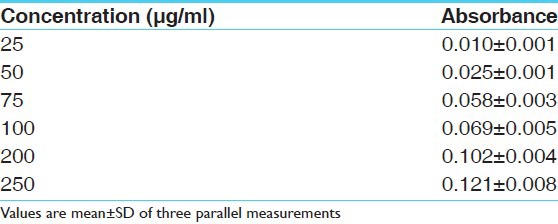

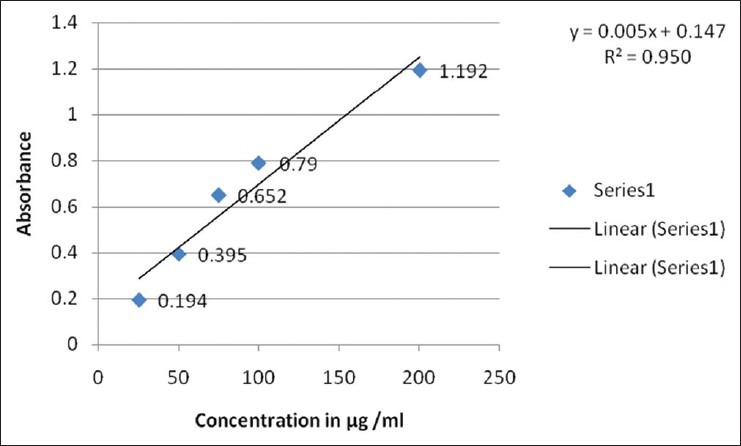

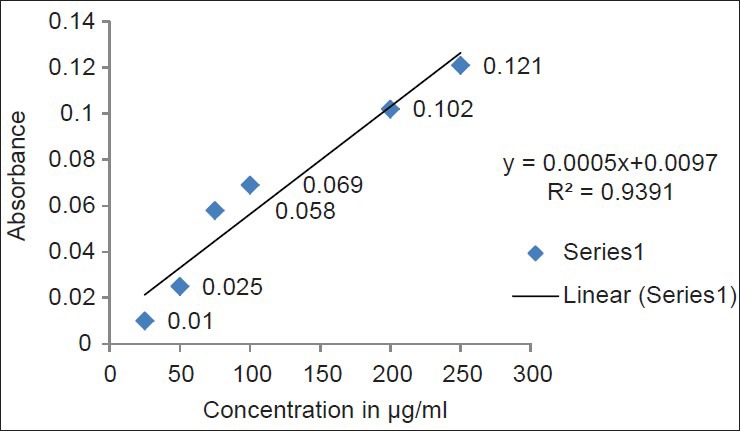

Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content of hydro alcoholic extract of Cassia fistula calculated as gallic acid equivalent of phenols was detected [Tables 5 and 6].

Table 5.

Absorbance of standard gallic acid at various concentrations (μg/ml) in total phenolic content determination model

Table 6.

Absorbance of hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp at various concentrations (μg/ml) in total phenolic content determination model

Free radicals are produced under certain environmental conditions and during normal cellular function in the body; these molecules miss an electron, giving them an electric charge. To neutralize this, charge, free radicals try to withdraw an electron from, or donate an electron to a neighboring molecule. The newly created free radical, in turn, looks out for other molecules and withdraws or donates an electron, setting off a chain reaction that can damage hundred of molecules. The total phenol content shows good linear relation in both standard and sample extracts [Figures 5 and 6]. Phenolic compounds are also very important plant constituents because their hydroxyl groups confer scavenging ability.

Figure 5.

Total phenolic content of standard gallic acid

Figure 6.

Total phenolic content of hydro alcoholic extract of fruit pulp

Conclusion

From the results obtained in the present study, it is concluded that, the hydro alcoholic extract of Cassia fistula fruit pulp shows antioxidant activity by inhibiting DPPH and hydroxyl radical, total phenol content and reducing power activities. The preliminary phytochemical investigation indicates that the Cassia fistula contains saponins, steroids, triterpenoids, and higher amount of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, tannins, glycosides, anthraquinones, gums, mucilage and amino acids. The presence of phenols and flavonoids in the plant plays a major role in controlling antioxidants and are also major constituents of anthraquinones. It contains phenolic groups which are responsible for higher antioxidant activity. The results of this study show that the hydro alcoholic extract of Cassia fistula can be used as a easily accessible source of natural antioxidants and as a possible food supplement or in pharmaceutical industry. However, the activity of Cassia fistula fruit pulp extract shows lower activity in DPPH and total phenol content as compared with standard. Further works may be taken-up the other extracts of various parts of Cassia fistula.

Acknowledgment

Authors are thankful to the Director, I.P.G.T. and R.A., Jamnagar, Gujarat, India for providing invaluable support and research facilities.

References

- 1.Madhavi DL, Deshpande SS, Sulunkhe DK. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. Food antioxidants: Technological, toxicological and health perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Upadhye M, Dhiman A, Shriwaikar A. Antioxidant activity of aqueous extract of Holostemma Annulare (Roxb) K Schum. Adv Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;10:127–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra J, Srivastava RK, Shukla SV, Raghav CS. Antioxidants in Aromatic and Medicinal plants. Science Tech Entrepreneur. 2007:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce DA. Oxygen radicals in disease. Adv Drug React Bull. 1987;127:476–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farber JL. Mechanisms of cell injury by activated oxygen species. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 10):17–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg N. Free radicals in diseases. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1998;16:241–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchioli R, Schweiger C, Levantesi G, Tavazzi L, Valagussa F. Antioxidant vitamins and prevention of cardiovascular disease: Epidemiological and clinical trial data. Lipids. 2001;36(Suppl):S53–63. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0683-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanner SA, Hughes J, Kelly CN, Buttriss J. A review of the epidemiological evidence for the antioxidant hypothesis. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:407–22. doi: 10.1079/phn2003543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlow SM. Food antioxidants. London: Elsevier; 1990. Toxicological aspects of antioxidants used as food additives; pp. 253–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgová S, Hermánek J, Gut I. Different antioxidant effects of polyphenols on lipid peroxidation and hydroxyl radicals in the NAPH-, Feascorbate-, Fe-microsomal systems. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1127–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tung YT, Wub JH, Huang CY, Kuo YH, Chang ST. Antioxidant activities and phytochemical characteristics of extracts from Acacia confuse bark. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:509–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel E. Hamamatsu, Japan: 1995. Nutritional benefits of flavonoids. International conference on food factors: Chemistry and cancer prevention; pp. C, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson R. The antioxidants of higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:969–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auudy B, Ferreira F, Blasina L, Lafon F, Arredondo F, Dajas R. Screening of antioxidant activity of three Indian medicinal plants, traditionally used for the management of neurodegenerative diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:131–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larson RA. The antioxidants of higher plants. Phytochemistry. 1998;27:969–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tripathi YB, Chaurasia S, Tripathi E, Upadhyay A, Dubey GP. Bacopa monniera Linn. As an antioxidant: Mechanism of action. Indian J Exp Biol. 1996;34:523–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sreejayan, Rao MN. Nitric oxide scavenging by curcuminoids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:7–105. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harborne JB. London: Chapman and Hall; 1984. Photochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandelwal KR. 2nd ed. Pune: Nirali Prakashan; 2009. Practical Pharmacognosy; pp. 149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kokate CK. Delhi: New Gyan Offset Printers; 2000. Practical Pharmacognosy; pp. 107–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar A, Ilavarasan R, Jayachandran, Decaraman M, Aravindhan P. Phytochemicals Investigation on a tropical plant in South India. Pak J Nutr. 2009;8:83–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadhu SK, Okuyama E, Fujimoto H, Ishibashi M. Separation of Leucas aspera, a medicinal plant of Bangladesh, guided by prostaglandin inhibitory and antioxidant activities. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:595–8. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravishankar MN, Srivastava N, Padh H, Rajani M. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of root bark of Hemidesmus indicus. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:153–60. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vani T, Rajani M, Sarkar S, Shishoo CJ. Antioxidant properties of the Ayurvedic formulation Triphala and its constituents. Int J Pharmacogn. 1997;35:313–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro CM, Montilla MP, Martin A, Jimenez J, Utrilla MP. Free radical scavenging and antihepatyotoxic activity of Rosamarinus tomentosus. Planta Med. 1993;59:312–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagul MS, Ravishankar MN, Padh H, Rajani M. Phytochemical evaluation and free radical scavenging activity of rhizome of Bergenia ciliate (Haw) Sternb: Forma ligulata Yeo. J Nat Rem. 2003;3:83–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oyaizu M. Studies on product of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44:307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quisumbing E. Katha Publishing Co. Inc. Phil; 1978. Medicinal Plants of the Phillippines; p. 977. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singleton VL, Rossi JA., Jr Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic acid- phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Viticult. 1965;16:144–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahidi F, Wanasundara PK. Phenolic antioxidants. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1992;32:67–103. doi: 10.1080/10408399209527581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice E, Miller CA, Paganga G. Free radical scavenging activity of plant polyphenolic. Gen Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:152–9. [Google Scholar]