Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence of microalbuminuria (MAU) among Chinese individuals without diabetes and the relationship between MAU and metabolic factors, individual socioeconomic status (SES), and regional economic development level.

Design

Cross-sectional study of prevalence of MAU.

Setting

152 urban street districts and 112 rural villages from northeast, north, east, south central, northwest and southwest China.

Participants

46 239 participants were recruited using a multistage stratified sampling design from 2007 to 2008. A total of 41 290 participants without diabetes determined by oral glucose tolerance test were included in the present study. Urine albumin/creatinine ratio results of 35 430 individuals were available.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Positive detection of MAU was determined using an ACR of 22.1–299.9 mg/g in men 30.9–299.9 mg/g in women.

Results

The prevalence of MAU in men was 22.4% and 24.5% in women. In developed, intermediate-developed and under-developed areas, the prevalence of MAU in men was 20.7%, 21.9% and 32.5%, respectively; in women the prevalence was 19.6%, 26.0% and 29.5%, respectively. The prevalence of MAU increased as the number of metabolic disorders present increased, and as the number of lower SES components increased (farmer, below university education level and low income). Prevalence of MAU in developed and intermediate developed areas had adjusted risk ratios of 0.52 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.60) and 0.65 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.76), respectively. Multivariate logistic analyses demonstrated MAU was strongly associated with older age, high-blood pressure, higher blood glucose low education level, low occupational level and residence in under-developed region.

Conclusions

Several factors had independent correlations to MAU in China: older age, metabolic abnormalities, lower SES level and living in economically under-developed areas, which encourage the development of strategies to lower the risk for MAU in these susceptible populations.

Keywords: Microalbuminuria, Prevalence, Socioeconomic Status, Regional Economic Development Level

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This is the first study on prevalence of microalbuminuria in Chinese individuals, that is based on a large population-based sample from diverse economic levels, with analyses accounting for the complex sampling design in order to provide a representative sample of 14 Chinese provinces.

The use of radioimmunoassay methods in urine albumin measurement increased sensitivity.

A limitation of this study is that it is cross-sectional and could not demonstrate cause–effect relationship.

Introduction

Microalbuminuria (MAU) is defined as a urinary albumin excretion ranging from 30 to 299 mg/24 h, and is a marker for chronic kidney damage and a risk factor for the progression of chronic kidney diseases (CKDs), cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cerebrovascular disease and mortality.1–3 The prevalence of MAU has been shown to vary within and between populations. For example, an analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, found the prevalence of MAU in the general US population was 6.1% for men and 9.7% for women.4 The prevalence of MAU has been estimated at 6% in Australians,5 6.6% in Netherland,3 20% in native Canadians6 and 36.9% in Singaporeans ≥40 years.7 Prevalence estimates from the same areas of Shanghai, China have varied widely between 5% and 19.4%.8 9 Factors that may have caused dissimilar prevalence estimates include varying definitions of MAU and different study methodologies. The excretion rate of urine albumin is unstable and may be affected by physiological factors such as sports participation and body position.10 11 High-performance liquid chromatography to determine urinary albumin concentrations revealed higher values compared to nephelometry, especially in the lower concentration range, which resulted in a higher prevalence of MAU.12 The urinary microalbuminuria/creatinine ratio method has been recommended due to a lack of reliable 24 h urine collection methods.

Risk factors for MAU and kidney diseases include components of the metabolic syndrome (MS) 13–16 and lower SES. Higher odds for MAU have been found in Singaporeans with lower educational obtainment (OR=1.76, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.52), lower income in retirement (OR=1.64, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.31), smaller housing type (OR=1.44, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.06) and coexistence of multiple low-SES factors (OR=2.37, 95% CI 1.56 to 3.60).7 Whereas affluence has been shown to be protective against CKD among blacks in the USA,17 higher occupational grade has been shown to be protective among whites in Europe.18

There are many international epidemiological studies on MAU, especially in diabetic populations, but there are few studies in non-diabetic Chinese populations. As the Chinese economy has developed over the last 30 years, the prevalence of metabolic diseases has increased with varying estimates in different parts of China. We reported that the prevalence of diabetes was not only associated with personal metabolic factors, but also with personal socioeconomic factors and regional economic development levels.19 The aim of the present study was to explore prevalence of MAU in China people without diabetes and to examine the relationship between MAU and metabolic factors (such as obesity, hypertension, hyperglycaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia), individual SESs (education, income and occupation) and regional economic development levels.

Methods

Subjects and experimental design

A multistage stratified sampling design was used to select participants that were greater than 20 years in age throughout 14 Chinese provinces. A detailed description of the study population and methodology has been published previously.19 A total of 46 239 participants were recruited that included 41 290 participants without diabetes as determined by an inquiry of disease history and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Among the enroled participants, 41 290 were used in the final statistical analyses, including 35 430 individuals with results of ACR. Geographical areas were divided into three categories based on the per capita gross domestic profit of China by provinces in 2006: (1) developed area (Chinese yuan (CNY) 23 663–65 473), (2) intermediate-developed area (CNY 13 123–19 363) and (3) under-developed area (CNY 6742–12 843).20 The highest educational level attained by the participants was dichotomised between under university level education and university level education or above. Income level was defined as annual family income in CNY and divided into three categories: (1) low (CNY <5000), (2) middle (CNY 5000 to <30 000) and (3) high (CNY ≥30 000).

Prior to conducting the assessments, interviewers received training on the questionnaire and how to explain each item to increase the reliability.19Waist circumference, weight and height were measured using standard methods.19 Blood pressure (BP) was measured two separate times at 5 min apart while participants were in the sitting position using an upright standard sphygmomanometer. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent from the participants was obtained after explaining the nature and possible consequences of the study procedures.

Blood was drawn from the antecubital vein in the morning after fasting for 10–14 h following 3 days of normal activity and diet. Blood samples were tested for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), triglycerides and plasma glucose (PG) levels. OGTTs 75 g were then performed 0.5 h later followed by another blood draw 2 h later. In addition, spot urine specimens were collected in the morning to measure ACR. All assessments were performed using a standard protocol that conformed to the international standards for definitions and measurements. PG was determined using the hexokinase method. Urine albumin concentration and serum level of immune reactivity insulin were measured using radioimmunoassay (RIA) in the central laboratory (North Biotechnology Institute, Beijing, China; inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation <5%). The picric acid method was used to measure the level of urine creatinine in the central laboratory. ACR was calculated as the urine microprotein (mg/L) divided by urinary creatinine (g/L), with urine creatinine levels less than 0.5 mg/g defined as missing values.

MAU and covariates

Patients with diabetes, as diagnosed according to the 1999 WHO criteria21 were excluded from the analyses. MAU was defined as a urinary ACR in the range of 21.1–299.9 mg/g in men and 30.9–299.9 mg/g in women.22 Central obesity was defined as a waist circumference greater than 90 cm in men and greater than 80 cm in women. Overweight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 kg/m2 and less than 30 kg/m2 and obesity was defined as a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2. Hypertension was defined as the participant having a history of high BP or BP greater than 140/90 mm Hg. Dyslipidaemia was defined as triglyceride at a level greater than or equal to 1.7 mmol/L, or HDL-c at a level less than 0.9 mmol/L for men and 1.0 mmol/L for women. Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) was defined as a fasting blood glucose level between 6.1 and 7.0 mmol/L, and 2 h post-load PG level less than 7.8 mmol/L. Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was defined as 2 h post-load PG level between 7.8 and 11.1 mmol/L, and a fasting PG level <6.1 mmol/L. Impaired glucose regulation (IGR) was defined as the presence of IFG or IGT. Matsuda insulin sensitivity index was calculated by the formula2,3

The value for the 25th percent in normal glucose tolerance (NGT) was determined as the cut-off value. Individuals with NGT values below the cut-off were defined as insulin resistant while all others were considered insulin sensitive.

Statistical analyses

SUDAAN software V.1.0 (Research Triangle Institute) was used to conduct weighted analyses to account for the complex stratified study design to adjust according to Chinese population data in 2006.20 Student’s t tests were used to examine the differences between continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the prevalence of MAU by sex, age, education level, occupational level, incomes, metabolic status and economic level. All p values were two-sided using <0.05 as the level for significance.

Results

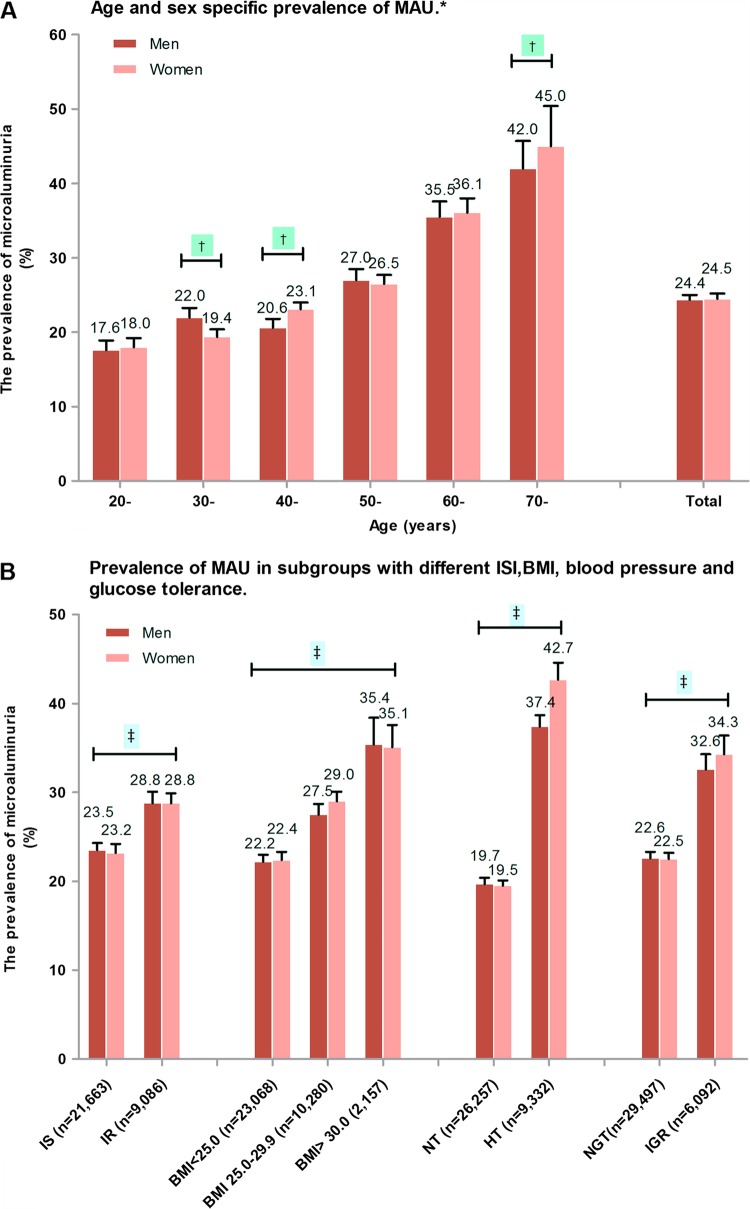

Among the 41 290 participants (mean age 43.9 years, range 20–100 years) included in this study, 35 470 participants had ACR data. There were 125 (0.35%, comprised of males 0.31% and females 0.39%) individuals with macroalbuminuria, defined as ACR≥300 mg/g. Among the qualified participants with MAU (300>ACR≥22.1 mg/g in men and 300>ACR≥30.9 mg/g in women), there were 24.4% in men (95% CI 23.6 to 25.4%) and 24.5% in women (95% CI 23.2 to 25.9%). The prevalence of MAU was higher in progressively increasing age categories both in men and in women (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

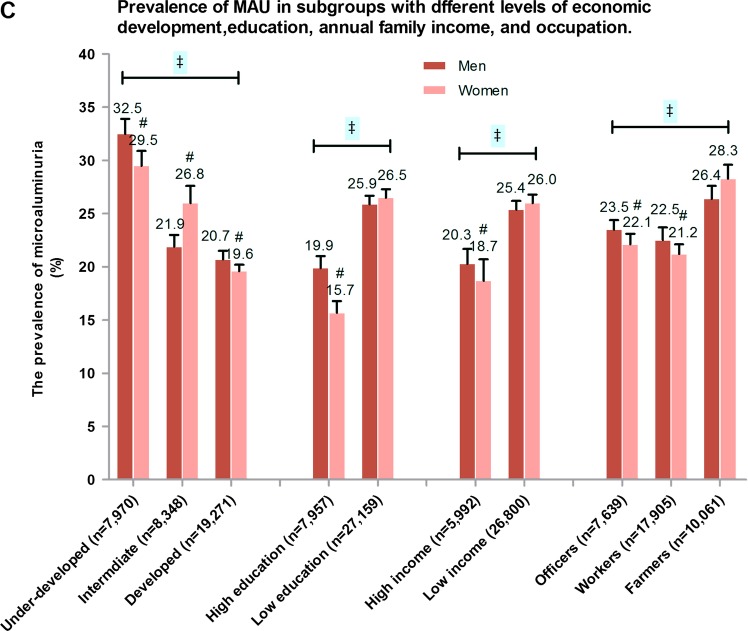

Prevalence of microalbuminuria (MAU) in various categories in Chinese without diabetes. (A) Age and sex-specific prevalence of MAU. (B) Prevalence of MAU in different obesity, blood pressure and insulin sensitivity index groups. (C) Prevalence of MAU in different education level, income level, profession and socioeconomic status level groups. *p Trend <0.001 among age groups, †p<0.001 men vs women in corresponding age subgroups; ‡p<0.01 in different ISI, BMI, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, economic developed areas, education level, incomes and profession groups; #p<0.01 men vs women in corresponding subgroups. BMI, body mass index; HT, hypertension; IS, insulin sensitivity; IR, insulin resistance; IGR, impaired glucose regulation; NGT, normal glucose tolerance; NT, normal blood pressure.

MAU was more prevalent in individuals who were insulin resistant, hypertensive, had IGR and had higher BMI (figure 1B). MAU prevalence also varied by SES; residence in under-developed areas, lower educational obtainment, lower income and occupation as a farmer were associated with an elevated prevalence of MAU (figure 1C).

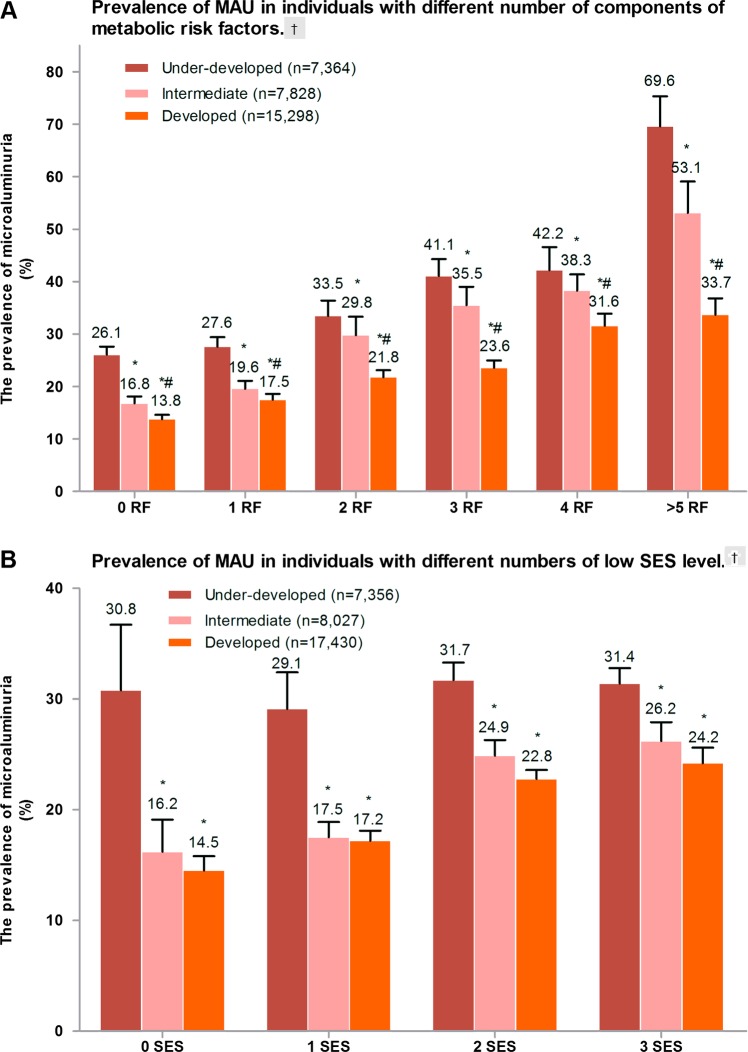

Metabolic abnormalities that were examined included IGR, hypertension, high TG, a low level of HDL-c, central obesity and insulin resistance (IR). The participants were placed into six groups according to the number of metabolic problems. As expected, the number of metabolic abnormalities increased the prevalence of MAU (figure 2A). Individuals from developed areas had significantly lower prevalence of MAU compared to intermediate-developed and under-developed groups that had a similar number of metabolic problems.

Figure 2.

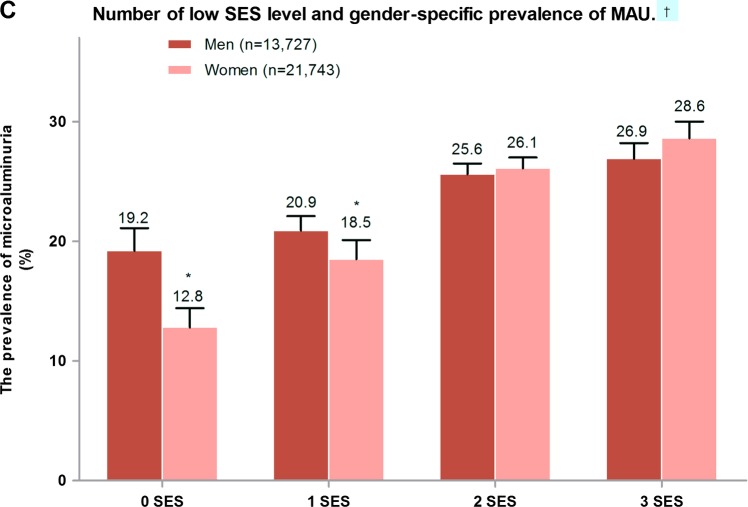

Prevalence of microalbuminuria (MAU) in individuals with different metabolic status and socioeconomic status (SES) level. (A) Prevalence of MAU in individuals with different numbers of components of metabolic risk factors. †p Trend<0.001 for comparing different risk factor numbers; *p<0.05 vs under-developed area; #p<0.05 vs intermediate developing area. (B) Prevalence of MAU in individuals with different numbers of low-SES level. †p Trend<0.001 for comparing different low SES numbers; *p<0.05 vs under-developed area. (C) Number of low-SES level and gender-specific prevalence of MAU. †p Trend <0.001 for comparing different low-SES numbers;*p<0.01 men vs women.

The SES components that were examined included occupation as a farmer, education level under university and annual family income less than CNY 30 000. The participants were placed into four groups according to the number of low-SES components present, and by the degree of development in the area in which they live (figure 2B). Prevalence of MAU increased as the number of low-SES components increased within different categories of development. There was higher prevalence of MAU in men who had 1 or less low-SES components. In those with 2–3 low-SES components, there was no significant difference between men and women in prevalence of MAU (figure 2C).

Sample characteristics according to ACR value quartiles are shown in table 1. Males had higher average metabolic values within each ACR quartile than females. Higher values for ACR were associated with higher prevalence of hypertension and higher values for other metabolic parameters.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants presented by ACR quartiles in Chinese men and women

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR (mg/g) | Q1 (0.5–6.8) | Q2 (6.9–12.5) | Q3 (12.6–26.3) | Q4 (≥26.4) | Q1 (0.5–6.8) | Q2 (6.9–12.5) | Q3 (12.6–26.3) | Q4 (≥26.4) |

| N=35 470 | 4265 | 3682 | 2960 | 2820 | 4589 | 5264 | 5839 | 6051 |

| Age (years) | 41.1 (40.4–41.9) | 42.8 (41.9–43.7)* | 45.2 (44.2–46.2)* | 48.3 (47.3–49.3)* | 41.6 (40.8–42.4) | 41.2 (40.5–42.0) | 43.2 (42.4–44.0)* | 47.6 (46.4–48.9)* |

| Overweight | 26.8 (23.2–23.5) | 27.9 (23.4–23.8) | 29.0 (24.3–24.6)* | 33.1 (30.2–36.1)* | 19.9 (17.7–22.4)† | 23.6 (21.6–25.7)*† | 21.7 (20.0–23.5)† | 27.3 (25.1–29.7)*† |

| Obese | 4.3 (3.1–6.0) | 5.5 (4.4–6.8)* | 4.5 (3.6–5.7) | 8.9 (7.3–10.9)* | 4.2 (3.3–5.3) | 3.3 (2.7–4.1)* | 3.9 (3.2–4.8) | 6.3 (5.2–7.5)*† |

| Central obesity | 24.2 (22.0–26.6) | 24.8 (22.7–27.1) | 24.7 (22.3–27.3) | 31.9 (29.1–34.9)* | 34.6 (32.0–37.4)† | 34.8 (32.6–37.1)† | 36.7 (34.5–38.9)*† | 45.9 (42.8–48.9)*† |

| HTG | 31.3 (31.0–33.8) | 29.7 (28.8–34.0) | 32.1 (29.3–35.0) | 38.0 (35.0–41.1)* | 21.1 (18.9–23.4)† | 18.9 (17.1–20.8)† | 20.6 (18.9–22.5)† | 27.0 (24.4–29.8)*† |

| Hypertension | 15.8 (14.2–17.6) | 24.0 (21.8–26.3)* | 29.9 (27.2–32.7)* | 43.0 (39.9–46.3)* | 13.3 (11.4–15.5) | 12.5 (11.2–13.9)† | 19.5 (17.8–21.4)*† | 36.1 (33.0–39.4)*† |

| IGR | 15.8 (13.7–18.1) | 17.2 (15.2–19.4) | 18.7 (16.4–21.2)* | 25.0 (22.3–27.8)* | 13.4 (11.7–15.2) | 13.8 (13.9–16.9)† | 15.4 (13.9–16.9)*† | 23.3 (20.4–26.4)* |

| IR | 24.0 (21.8–26.4) | 24.7 (22.4–27.2) | 22.8 (20.4–25.4) | 30.1 (27.2–33.1)* | 22.5 (20.4–24.8) | 23.4 (21.5–25.5) | 24.0 (22.0–26.1) | 28.0 (25.6–30.5)* |

*p<0.05 vs ACR 0.5 to 6.8 mg/g.

†p<0.05 vs men at same ACR quartiles.

ACR, albumin/creatinine ratio; HTG, serum triglyceride ≥1.7 mmol/L; IGR, impaired glucose regulation, IR, insulin resistant.

The average MAU for males and females in intermediate-developed and developed areas were significantly lower than in under-developed areas (table 2). There were no age differences between the three economic development areas; BMI, BP, blood glucose, insulin and IR were all higher in developed areas than in under-developed areas.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics for men and women presented by level of economic development

| Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under developed | Intermediate developed | Developed | Under developed | Intermediate developed | Developed | |

| N=41 290 | 4340 | 3376 | 8482 | 6404 | 5179 | 13 509 |

| Age (year) | 43.7 (43.4, 44.0) | 43.8 (43.0, 44.5) | 44.2 (43.3, 45.2) | 43.7 (43.1, 44.2) | 43.7 (42.6, 44.9) | 43.7 (43.2, 44.3) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.3 (23.2 ,23.5) | 23.6 (23.4, 23.8) | 24.5 (24.3, 24.6)*† | 22.9 (22.8, 23.1) | 23.1 (23.0, 23.2) | 23.5 (23.4, 23.6)*† |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 82.1 (81.6, 82.6) | 80.5 (79.9, 81.1)* | 85.2 (84.9, 85.6)*† | 77.2 (76.8, 77.6) | 76.2 (75.5, 76.9)* | 78.2 (77.9, 78.5)*† |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 119.1 (118.2, 120.0) | 121.6 (120.5, 122.7)* | 125.8 (125.2, 126.4)*† | 115.4 (114.5, 116.3) | 118.5 (117.3, 119.7)* | 120.6 (120.1, 121.1)*† |

| Fasting PG (mmol/L) | 4.9 (4.9, 5.0) | 4.9 (4.9, 5.0) | 5.1 (5.0, 5.1)*† | 4.9 (4.9, 4.9) | 4.8 (4.8, 4.9) | 5.0 (5.0, 5.1)*† |

| PG at 30’ (mmol/L) | 8.1 (8.0, 8.2) | 8.6 (8.5, 8.7)* | 9.0 (8.9, 9.1)*† | 7.5 (7.5, 7.7) | 8.1 (8.0, 8.2)* | 8.4 (8.4, 8.5)*† |

| PG at 120’ (mmol/L) | 5.8 (5.7, 5.8) | 6.2 (6.1, 6.3)* | 6.1 (6.1, 6.2)* | 5.9 (5.8, 6.0) | 6.2 (6.1, 6.3)* | 6.2 (6.2, 6.3)* |

| ACR (mg/g) | 14.1 (7.2, 27.1) | 10.4 (6.6, 19.7)* | 9.8 (6.0, 18.8)*† | 17.1 (8.2, 37.0) | 15.4 (9.3, 33.6)* | 13.3 (7.6, 25.1)*† |

| Fasting serum IRI (mU/L) | 6.4 (4.8, 8.7) | 6.4 (4.4, 9.1) | 7.3 (5.1, 10.4)*† | 6.6 (4.9, 8.8) | 6.5 (4.6, 9.1) | 7.1 (5.1, 10.0)*† |

| Serum IRI at 30’ (mU/L) | 28.0 (16.6, 47.4) | 30.2 (16.7, 49.4) | 39.1 (22.4, 67.7)*† | 31.5 (19.4, 50.4) | 30.9 (20.1, 49.3) | 39.5 (24.7, 61.9)*† |

| Serum IRI at 120’ (mU/L) | 21.1 (11.8, 35.1) | 19.9 (11.6, 35.4) | 26.6 (15.3, 47.0)*† | 24.3 (16.5, 42.2) | 25.9 (11.8, 37.3) | 30.7 (18.8, 50.1)*† |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.57 (4.52, 4.62) | 4.62 (4.57, 4.67) | 4.79 (4.76, 4.83)*† | 4.55 (4.51, 4.59) | 4.68 (4.62, 4.74)* | 4.76 (4.73, 4.79)*† |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.23 (0.91, 1.89) | 1.21 (0.85, 1.83) | 1.37 (0.93, 2.16)* | 1.17 (0.85, 1.66) | 1.05 (0. 78, 1.55)* | 1.09 (0.78, 1.63)* |

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.25 (1.24, 1.27) | 1.24 (1.22, 1.26) | 1.26 (1.25, 1.27) | 1.33 (1.32, 1.35) | 1.32 (1.30, 1.33) | 1.40 (1.38, 1.41)*† |

| HOMA-IR | 1.36 (1.00, 1.88) | 1.38 (0.94, 2.01) | 1.64 (1.15, 2.38)*† | 1.40 (1.03, 1.95) | 1.39 (0.95, 2.00) | 1.59 (1.15, 2.26)*† |

| Matsuda ISI | 9.3 (6.5, 12.3) | 8.8 (6.0, 12.8) | 6.9 (4.7, 10.0)*† | 8.6 (6.2, 11.8) | 8.5 (5.8, 11.7) | 7.1 (4.9, 9.5)*† |

*Significant difference compared with developed area, p<0.01.

†Significant difference compared with intermediate-developed area, p<0.01.

SI conversion factors: to convert insulin to pmol/L, multiple values by 6.945.

ACR, albumin creatinine ratio; BP, blood pressure; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein-cholesetrol;; IRI, immunoreactive insulin; ISI, insulin sensitivity index; PG, plasma glucose.

Three multivariate logistic models were used to examine the relationship between demographic data, metabolic factors, personal SES, rural/urban residence and regional economic development (table 3). In model 1, old age, increase of plasma glucose (PG) and hypertension were independently associated with MAU. In model 2, where SES components were included, low-education level and low annual family income category were also associated with MAU. In the model 3, individual residence, where regional economic development levels were added. The following variables were independently associated with MAU: older age, higher blood glucose, high BP, low-education levels, and low-regional economic development level.

Table 3.

Results from multivariate logistic regression analyses for individuals with ACR ≥22.1 mg/g in men 30.9 mg/g in women*

| Model 1 (OR, 95% CI) | Model 2 (OR, 95% CI) | Model 3 (OR, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women vs men) | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.17) | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.17) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) |

| Age (per 10 years increment) | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.21) | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.18) | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.18) |

| BMI (per/2 kg/m2 increment) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) |

| Blood pressure (hypertension vs normotension) | 2.09 (1.84 to 2.37) | 2.10 (1.85 to 2.40) | 2.17 (1.90 to 2.48) |

| Insulin sensitivity † (IS vs IR) | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.17) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.23) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.25) |

| 2 h plasma glucose (per 2 mmol/L increase) | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.21) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.23) |

| Education (less than college vs college) | NI | 1.37 (1.18 to 1.60) | 1.34 (1.15 to 1.55) |

| Annual family income (<30 000 vs ≥30 000 CNY) | NI | 1.26 (1.07 to 1.49) | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.27) |

| Occupation (workers vs officials or intellectuals) | NI | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.90) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) |

| Occupation (farmers vs officials or intellectuals) | NI | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.22) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.20) |

| Development ‡ (developed vs under developed) | NI | NI | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.60) |

| Development ‡ (intermediate developed vs under developed) | NI | NI | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.76) |

| Residence (rural vs urban) | NI | NI | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) |

*ORs were calculated using multivariate logistic models. All covariates listed were included in the model simultaneously. Serum triglycerides, smoking status included the three models without significant difference not presented.

†Insulin resistance was defined as Matsuda ISI <25th centile in individuals with normal glucose tolerance.

‡Economic development levels were placed into three categories (under developed, intermediate developed and developed).

BMI, body mass index; CNY, Chinese Yuan; IR, insulin resistance; IS, insulin sensitivity; NI, not included in the model.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

To our knowledge, this is the largest population-based study of MAU in Chinese individuals without diabetes. The prevalence of MAU was 24.4% in males and 24.5% in females. Individuals with higher level of ACR had higher prevalence of hypertension, obese/overweight and IGR (table 1). In contrast to the higher level of BP, PG, serum triglycerides and IR in economically developed regions, the level of ACR was lower in economically developed regions (table 2). Results from the multivariate analyses suggest that increasing age, high-BP and increased blood glucose were independent risk factors for MAU. Results from the univariate analyses demonstrated that MAU was more prevalent in participants with IR than those who were insulin sensitive. However, after adjusting for blood glucose level in multivariate analyses, IR was not significantly associated with MAU. The prevalence of MAU increased as the number of metabolic abnormalities increased in developed areas and in under-developed areas; over 50% of participants with five metabolic abnormalities in under-developed and intermediate-developed areas had MAU. Some low-SES parameters were associated with MAU. For example, the prevalence of MAU was higher in individuals with under a university education and in those who had low-annual family income. Level of regional economic development was significantly associated with MAU with the intermediate-developed and developed areas having 35% and 48% lower prevalence than under-developed areas, respectively. This association appeared to be independent of metabolic abnormalities and low SES.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of this study included the large population-based sample from diverse economic levels, with analyses accounting for the complex sampling design to provide a representative sample of 14 Chinese provinces; the use of RIA methods to test for urine albumin to increase sensitivity. The limitations of our study included the cross-sectional design that limited the ability to make cause–effect inferences, and the one-time collection of spot urine specimens due to a large variability in albumin excretion rates that did not allow an evaluation for the persistence of MAU.

Comparison with other studies

Both men and women in our study had a significantly higher prevalence of MAU compared to individuals in developed countries.4 5 Prevalence of MAU in the general US population was 6.1% in men and 9.7% in women4 and 6% in Australians.5 Prevalence of MAU in the Chinese participants of this study was lower than the prevalence found in Singaporeans aged 40–80 years, which may be explained by the fact that study used lower cut-off values to define MAU (ACR≥17 mg/g for men and≥25 mg/g for women).7 However, a similar result (19.4%) was observed in Shanghai, China.8 This study was consistent with studies in Singapore where higher odds of MAU were found in individuals with lower educational obtainment, lower income in retirement, smaller housing type and coexistence of multiple low-SES factors.7

Meaning of the study

MAU has been recognised as an early sign of renal damage, and a significant predictor of end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in patients with diabetes.13–15 In patients with type 1 diabetes, MAU is considered an indicator of the third stage of diabetic nephropathy.13 A recent study demonstrated methods that decrease MAU may reduce the risk for end-stage renal disease.24 25 Endothelial dysfunction and microinflammation of vasculature have been proposed as pathogenic mechanisms of MAU, which also links MAU to vascular atherosclerosis. Monitoring MAU levels may help identify endothelial dysfunction and vascular microinflammation in participants with obesity, high-BP, dyslipidaemia and blood glucose.1 For this reason, the WHO has included MAU in their criteria for the MS.14 MAU was strongly associated with older age, obesity, metabolic abnormalities, lower SES and residence in lower economic development areas. Limited access to healthcare services for low-SES participants could help explain some of the association between SES and MAU. Many studies have shown an association between MAU and C reactive protein (CRP) level, a marker for microinflammation26 which has been shown to be higher in low healthcare utilisation and low-SES populations. Periodontal diseases have also been shown to be more common in low-SES populations and are associated with increased CRP level. We did not have data to explore the association between periodontal diseases and MAU. Additional research could help clarify the relationship between SES and MAU, especially the underlying mechanism. A higher prevalence of MAU in under-developed areas could be due in part to inadequate availability of healthcare services and to unfavourable environmental factors. The development of strategies to lower the risk for MAU in these susceptible populations should be emphasised. Besides measures to prevent and control metabolic disorders, we propose that reforming the health system, improving access to health facilities, prompting health education, preventing periodontal diseases especially in low-SES population and in under-development regions, may reduce the prevalence of MAU and reduce the incidence of CVD and mortality in general population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, MAU was strongly associated with older age, metabolic abnormalities, lower SES and residence in lower economic development areas. It is suggested that future research studies explore the extent to which MAU could mediate the association between low-SES and metabolic, CVD and cerebrovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients for their cooperation in the study. The authors also thank all the members of Chinese National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study (2007 to 2008) who contributed in recruiting participants and obtaining samples.

Footnotes

Contributors: JX, XX, JL, JW, WJ, LJ, ZS, JL, HT, QJ, DZ, JG, GC, LC, XG, ZZ, QL, ZZ, ZY and WY contributed to the acquisition of data. JX, XX and ZY were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data. JX, XX and WY drafted the manuscript. JX and XX contributed equally to the study.

Funding: The project was supported by grants from Chinese Medical Association Foundation and Chinese Diabetes Society (WY), and National 973 Programme (2011CB504001 JX).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The research ethics board of China–Japan Friendship Hospital approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bigazzi R, Bianchi S, Baldari D, et al. Microalbuminuria predicts cardiovascular events and renal insufficiency in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1998;16:1325–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stehouwer CD, Gall MA, Twisk JW, et al. Increased urinary albumin excretion, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: progressive, interrelated, and independently associated with risk of death. Diabetes 2002;51: 1157–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, et al. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 2002;106:1777–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CA, Francis ME, Eberhardt MS, et al. Microalbuminuria in the US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:445–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins RC, Polkinghorne KR, Briganti EM, et al. Prevalence of albuminuria in Australia. Aus Diab Kidney Int 2004;66(S92):S22–4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15485411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zacharias JM, Young TK, Riediger ND, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of albuminuria on a Canadian First Nation: a community-based screening study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabanayagam C, Shankar A, Saw SM, et al. Socioeconomic status and microalbuminuria in an Asian population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:123–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia W, Gao X, Pang C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of albuminuria and chronic kidney disease in Chinese population with type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose regulation: Shanghai diabetic complications study (SHDCS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:3724–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, Xu M, Bi Y, et al. Association between higher serum fetuin-A concentrations and abnormal albuminuria in middle-aged and elderly Chinese with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2462–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt JR, Jacobs A, Raissy HH, et al. Orthostatic proteinuria and the spectrum of diurnal variability of urinary protein excretion in healthy children. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:1131–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson IG, Greene SA, Smith MA, et al. Urine albumin to creatinine ratio-response to exercise in diabetes. Arch Dis Child 1985;60:305–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkman JW, Bakker SJ, Gansevoot RT, et al. Which method for quantifying urinary albumin excretion gives what outcome? A comparison of immunonephelometry with HPLC. Kidney Int 2004;66(S92):S69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mogensen CE. Microalbuminuria predicts clinical proteinuria and early mortality in maturity-onset diabetes. N Engl J Med 1984;310:356–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobal F, Deshmukh A, Shah S, et al. Triad of metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, and coronary heart disease with a focus on microalbuminuria—death by overeating. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2303–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannel WB, Stampfer MJ, Castelli WP, et al. The prognostic significance of proteinuria: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1984;108:1347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chew GT, Gan SK, Watts GF. Revisiting the metabolic syndrome. Med J Aust 2006;185:445–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins D, Tareen N, Zadshir A, et al. The association of poverty with the prevalence of albuminuria: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:965–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Qaoud TM, Nitsch D, Wells J, et al. Socioeconomic status and reduced kidney function in the Whitehall II Study: role of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;58:389–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1090–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luepker RV EA, McKeigue P, Reddy KS. Cardiovascular survey methods. 3rd edn Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Bureau of Statistics of China China statistical yearbook, 2006. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2006/indexeh.htm (accessed 26 Feb 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houlihan CA, Tsalamandris C, Akdeniz A, et al. Albumin to creatinine ratio: a screening test with limitations. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:1183–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdul-Ghani MA, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA. Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1130–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asselbergs FW, Diercks GF, Hillege HL, et al. Effects of fosinopril and pravastatin on cardiovascular events in subjects with microalbuminuria. Circulation 2004;110:2809–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003;348:383–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pravenec M, Kajiya T, Zídek V, et al. Effects of human C-reactive protein on pathogenesis of features of the metabolic syndrome. Hypertension 2011;57:731–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.