Abstract

Background

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis (HD) suffer from a high symptom burden. However, there is significant heterogeneity within the HD population; certain subgroups, such as the elderly, may experience disproportionate symptom burden.

Objectives

The study's objective was to propose a category of HD patients at elevated risk for symptom burden (those patients who are not transplant candidates) and to compare symptomatology among transplant ineligible versus eligible HD patients.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Setting/Subjects

English-speaking, cognitively intact patients receiving HD and who were either transplant eligible (n=25) or ineligible (n=32) were recruited from two urban HD units serving patients in the greater New York City region.

Measurements

In-person interviews were conducted to ascertain participants' symptom burden using the Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI), perceived symptom bother and attribution (whether the symptom was perceived to be related to HD treatment), and quality of life using the SF-36. Participants' medical records were reviewed to collect demographic and clinical data.

Results

Transplant ineligible (versus eligible) patients reported an average of 13.9±4.6 symptoms versus 9.2±4.4 symptoms (p<0.01); these differences persisted after adjustment for multiple factors. A greater proportion of transplant ineligible (versus eligible) patients attributed their symptoms to HD and were more likely to report greater bother on account of the symptoms. Quality of life was also significantly lower in the transplant ineligible group.

Conclusions

Among HD patients, transplant eligibility is associated with symptom burden. Our pilot data suggest that consideration be given to employing transplant status as a method of identifying HD patients at risk for greater symptom burden and targeting them for palliative interventions.

Introduction

There are nearly 400,000 chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients in the United States, with over 115,000 incident cases of End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) in 2010 alone.1 Of the incident ESRD cases, nearly 30% are 75 years of age or older and have poor survival following HD initiation.2 Many other patients new to HD fit demographic categories that also portend a poor prognosis. Those with frailty,3 multiple comorbidities,4 dementia,5 inability to ambulate,6 and who reside in nursing homes7 have survival rates similar to patients with advanced cancer.8 These patients are almost universally medically disqualified for renal transplant.

Prior studies have reported that HD patients suffer from a symptom burden similar to patients with end-stage lung disease, heart disease, and solid tumors.9–11 These symptoms may be due to concurrent illness, uremia, or both. Furthermore, treatment of ESRD often contributes to substantial symptom burden12 that is poorly controlled and addressed.8

Little is currently known regarding symptom burden in the subpopulations with the highest risk of death, such as those with advanced age, multiple comorbidities, or functional debility. Moreover, there is no current mechanism for identifying patients most likely to experience increased symptom burden. Accordingly, this pilot study sought to (1) propose a category of HD patients potentially at risk for greater symptom burden—i.e., patients who are transplant ineligible, a category that encompasses age, comorbidities, cognitive decline, functional status, as well as their physicians' subjective judgment of poor likelihood of long-term survival; and (2) compare symptom burden in this population to an age-matched, transplant eligible control population.

Methods

Sample assembly

Patients were recruited from two urban, freestanding HD units in New York City with a total patient census of approximately 500 HD patients. A member of the research team approached potential subjects during HD treatment. All interviews were conducted between July 2011 and May 2012. Both cases and controls were assembled using a convenience sampling approach.

Treating nephrologists were first approached by the investigators to identify patients of theirs deemed transplant ineligible on the basis of medical or surgical risk—patients with behavioral or psychiatric contraindications to transplantation were not considered for inclusion in this study. Transplant ineligible HD patients were excluded if they did not speak English or failed a six-item cognitive screener.13

Forty-six patients receiving outpatient HD treatments were identified by their nephrologists as transplant ineligible, English speaking, and without dementia. These patients were approached by a member of the research team about participating in the study. Three patients were found to lack adequate English speaking skills, one declined participation, and one died prior to being approached. Forty-one patients consented; however, five lacked physical stamina to undergo the interview, three revoked consent, and one failed the cognitive screener. A review of the full census showed that approximately 20 patients were not considered for recruitment due to lack of English, while an additional 20 were not considered for recruitment due to dementia. In total, approximately 18% of the total census was medically or surgically ineligible for transplantation.

Transplant eligible HD patients over the age of 65 served as controls. Patients were identified by their treating nephrologist as being transplant eligible and recruited by a research team member. Exclusion criteria were the same as for transplant ineligible patients: inability to speak English or pass a six-item cognitive screener. Of the 29 transplant eligible patients who consented, three revoked consent and one failed the cognitive screener.13

Data collection

The Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI) and the Short Form (SF-36) were administered during an in-person interview administered by a research team member. The DSI elicited symptom prevalence, bothersomeness, and patient perception of symptom attribution. We enumerated symptoms assessed by the DSI that were depression related, including feeling tired or lack of energy, decreased appetite, difficulty concentrating, worrying, feeling anxious, trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, feeling irritable, feeling sad, and feeling nervous. Patients' records were reviewed to identify medications, number of years on dialysis, and comorbid conditions.14 Patients were interviewed during HD and interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes. The Weill Cornell Medical College institutional review board approved the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables. Associations between transplant eligibility status (yes versus no) and demographic, clinical, and symptom burden (number of symptoms reported, number of pills taken daily) were performed using t-tests or χ2 tests as appropriate. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, in which the goal was to identify all possible differences between groups and because of the small sample size, p values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. A multiple linear regression model was constructed to determine whether transplant eligibility status was independently associated with total number of symptoms reported. Three models were examined. First tested was a model entering only group transplant status, months on dialysis, and Charlson comorbidity score. Variables were selected because they (1) evidenced large differences between groups or p values of <0.10 and (2) were scales as contrasted with single-item indicators. A second model added demographic variables that showed trends for differences and were of theoretical importance: age, gender, and race. The number of covariates included was kept small (not more than five) due to the small sample size. A third model added the variables opioids and phosphorus binders. Collinearity diagnostics were performed. Tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values were all in the acceptable range, confirming that collinearity was not a problem in this analysis.

Although the DSI has been examined using linear multiple regression analyses in the past,15 the measure has been constructed as an index or simple sum of symptoms; thus in sensitivity analyses, a Poisson regression (PR) model for count data was examined. The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the DSI indicated that the data fit both a normal and Poisson distribution (full sample and also within each comparison group).

Results

Bivariate results

The bivariate results comparing participant characteristics by transplant eligibility status are shown in Table 1. Transplant ineligible patients were on dialysis for a median of 48 months—interquartile range (IQR) 67—versus 32 months (IQR 42) for transplant eligible patients (p<0.05). Charlson comorbidity scores were higher for the transplant ineligible (versus eligible) group: 7.0±2.4 versus 5.9±1.7 (p=0.072). The two groups were similar in age and had similar medication use profiles. Although not significant because of the small sample size, the transplant ineligible patients tended to be male and white non-Hispanic.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Health Status

| Transplant ineligible | Transplant eligible | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 32.0 | 25.0 |

| Mean age (SD) | 70.4 (13.6) | 72.1 (6.3) |

| % Male | 62.5 | 56.0 |

| % White | 59.0 | 48.0 |

| % African American | 31.0 | 36.0 |

| Mean months on dialysis* | 83 (90) | 42 (39) |

| Median months on dialysis (range) | 48 (5–368) | 32 (2–160) |

| Mean charlson comorbidity index | 7.0 (2.4) | 5.9 (1.7) |

| Mean number of symptoms reported† | 13.9 (4.6) | 9.2 (4.4) |

| Mean number of depressive symptoms reported †‡ | 5.5 (2.4) | 3.2 (2.0) |

| Mean number of medications | 11.7 (4.2) | 11.5 (4.1) |

| Mean number of pills taken daily | 12.8 (5.6) | 11.32 (4.8) |

| % Taking antidepressants | 25.0 | 20.0 |

| % Taking sleep aids | 6.0 | 8.0 |

| % Taking opioids | 28.0 | 12.0 |

| % Taking benzodiazepines | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| % Taking antihypertensives | 78.0 | 72.0 |

| % Taking lipid-lowering drugs | 50.0 | 44.0 |

| % Taking vitamin D | 56.0 | 64.0 |

| % Taking phosphorus binders | 66.0 | 80.0 |

| % Taking calcimimetic | 16.0 | 4.0 |

p<0.05; †p<0.01; ‡depressive symptoms, decreased appetite, feeling tired or lack of energy, difficulty concentrating, worrying, feeling nervous, trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, feeling irritable, feeling sad, and feeling anxious.

The transplant ineligible group reported an average 13.9±4.6 symptoms versus 9.2±4.4 symptoms in the transplant eligible group (p<0.01).

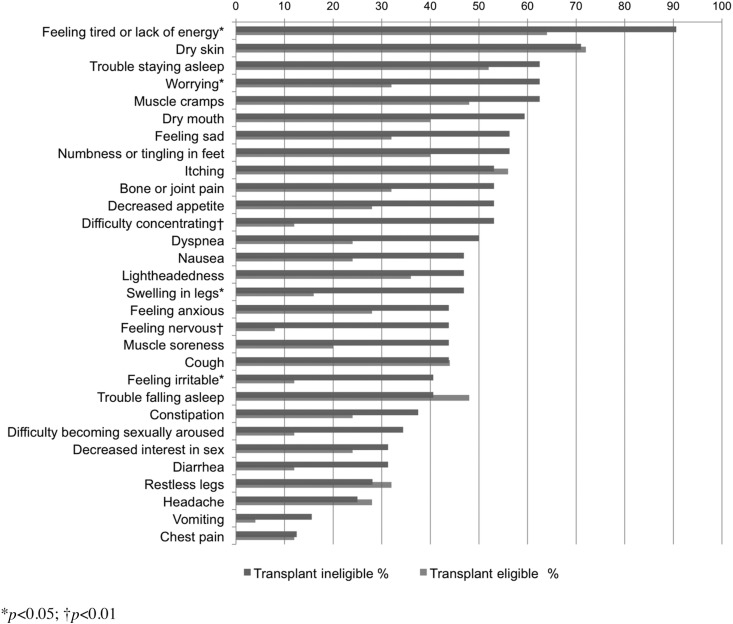

Individual symptom prevalence is shown in Figure 1. Transplant ineligible patients reported higher symptom prevalence in 24 of the 30 symptom domains, with significant differences in Feeling tired or Lack of energy, Worrying, Swelling in legs, Feeling irritable (p<0.05), and Feeling nervous (p<0.01). In addition, the transplant ineligible group endorsed more depressive-type symptoms from the DSI (5.5±2.4 versus 3.2±2.0, p<0.01).

FIG. 1.

Symptom prevalence among transplant eligible and transplant ineligible patients.

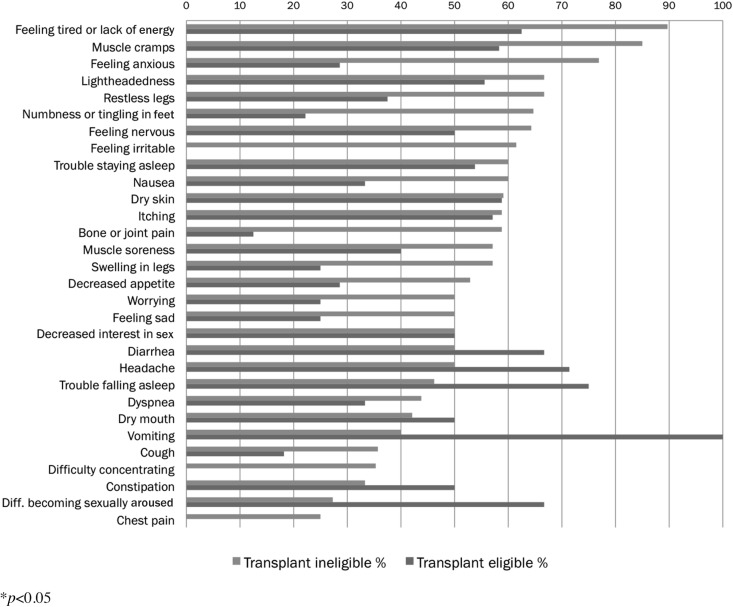

Subject-reported symptoms attributed specifically to the HD procedure are listed in Figure 2. A greater proportion of transplant ineligible patients attributed symptoms to HD than did transplant eligible patients in 22 out of 30 symptom categories. Transplant eligible patients were less likely to endorse symptoms related to HD treatment, diet, or medication.

FIG. 2.

Symptoms related to hemodialysis.

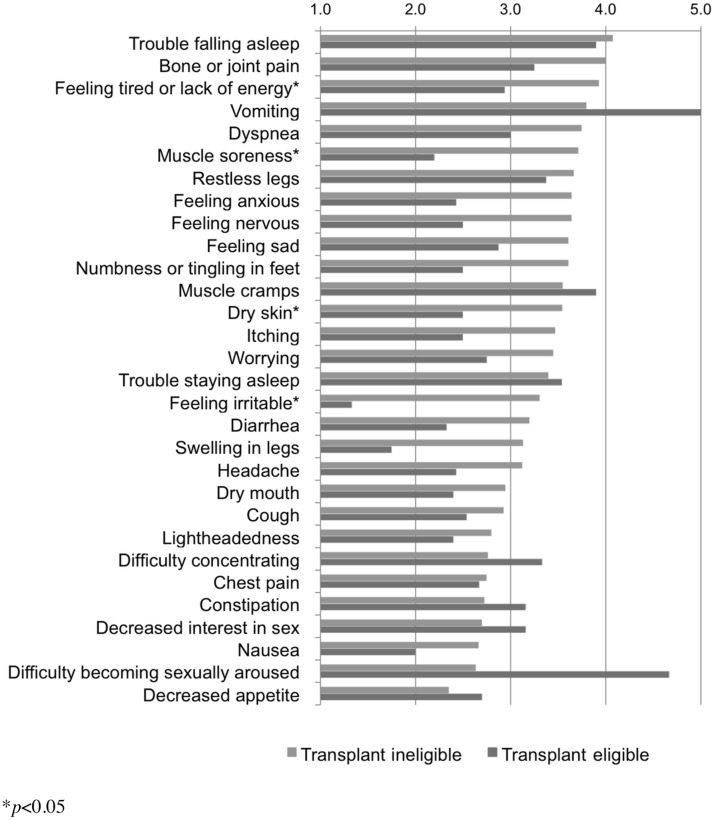

Participants were asked to assess bothersomeness of each symptom reported from 1 to 5: “Not at all,” “A little bit,” “Somewhat,” “Very much,” or “Quite a bit.” Results are reported in Figure 3. Significant differences were seen in Feeling tired or Lack of energy, Muscle soreness, Dry skin, and Feeling irritable (p<0.05).

FIG. 3.

Symptom bothersomeness.

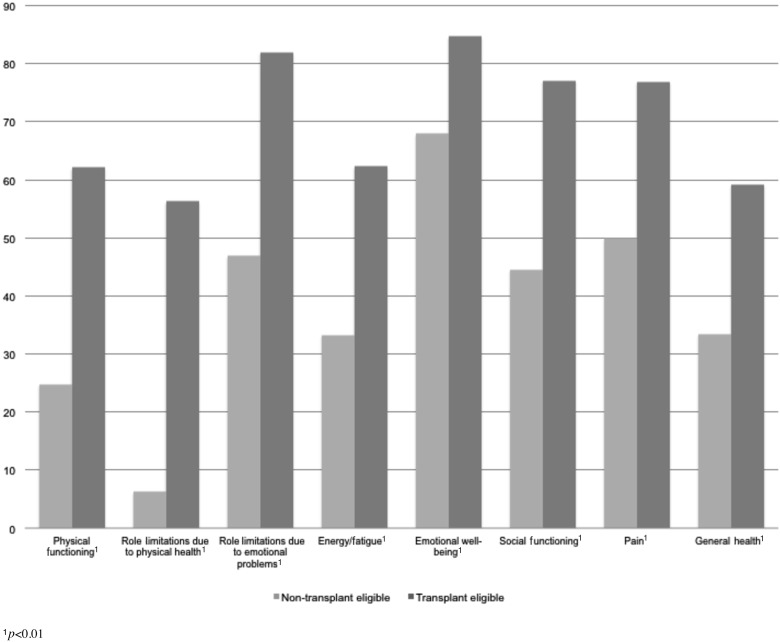

Finally, the SF-36 interview instrument was used to assess patients' limitations in daily life due to physical or emotional health problems (see Figure 4). Each of the eight component scores (e.g., Physical functioning, Energy/fatigue, Pain, General health) was significantly lower for the transplant ineligible (versus eligible) group (p<0.01), reflecting lower overall quality of life (see Figure 4).

FIG. 4.

Transplant ineligible and transplant eligible quality of life.

Multivariate results

The results of the multiple regression analyses are shown in Table 2. Three models are shown. The first is a simple linear regression, entering group status, months on dialysis, and the Charlson comorbidity index score. Controlling for these variables, the most important predictor of symptoms is transplant eligibility group status (p<0.001). No other variable is significant. The addition of age, gender, and race status in the model does not change these results. Only gender shows a trend toward significance. Transplant group status remains the only significant variable (p<0.001). The addition of opioids and phosphorus binder medications does not change these results. The results of a sensitivity analysis using a Poisson model are consistent with the multiple regression with a few exceptions. In model 1 there was a trend toward significance for the Charlson comorbidity measure (p=0.108) for the linear multiple regression (MR) model, which was significant using the PR model (p=0.037). For models 2 and 3 there is a similar finding for gender (model 2 MR p=0.059, PR p=0.013; model 3 MR p=0.067, PR p=0.014).

Table 2.

Results of Multiple Regression Predicting Number of Symptoms (n=57).

| |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. error | Sig. | B | Std. error | Sig. | B | Std. error | Sig. | |

| (Constant) | 11.664 | 1.949 | <0.001 | 13.43 | 4.653 | 0.006 | 11.599 | 4.880 | 0.021 |

| Group (ineligible=1, control=0) | 5.025 | 1.290 | <0.001 | 4.957 | 1.298 | <0.001 | 5.045 | 1.381 | 0.001 |

| Months on dialysis prior to interview | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.484 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.770 | −0.001 | 0.009 | 0.958 |

| Charlson score | −0.464 | 0.284 | 0.108 | −0.301 | 0.302 | 0.324 | −0.338 | 0.304 | 0.272 |

| Age | – | – | – | −0.055 | 0.063 | 0.388 | −0.034 | 0.066 | 0.611 |

| Participant female | – | – | – | 2.363 | 1.224 | 0.059 | 2.360 | 1.259 | 0.067 |

| Participant white | – | – | – | 0.658 | 1.263 | 0.605 | 0.368 | 1.290 | 0.777 |

| Taking opioids | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.773 | 1.639 | 0.285 |

| Taking phosphorus binders | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.762 | 1.449 | 0.602 |

Discussion

Our pilot data show that transplant eligibility status correlates strongly with symptom burden. Patients who were transplant ineligible had significantly greater symptom burden, even after adjusting for age, comorbidity, number of months on HD, race, and gender. Furthermore, transplant ineligible patients reported that their symptoms were more bothersome than a cohort of age-matched transplant eligible patients.

Our findings further suggest that some of the symptom burden may be iatrogenic for both transplant eligible and ineligible HD patients. Many of the symptoms commonly reported by HD patients may be caused or exacerbated by HD treatment itself. Given that many treatments applied to HD patients are not evidence based, treatment modification—focusing on treatment of patient symptoms rather than strict adherence to practice guidelines—may be a reasonable way to improve patient outcomes. For example, treatment of hyperphosphatemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and hypertension may increase symptoms, with little proven benefit.15 The optimal treatment goals, for these and other complications of ESRD, are unknown and await further study.

Mental health symptoms contributed extensively to overall symptom burden among transplant ineligible HD patients. Little data exist regarding the efficacy of treating these patients for underlying depression and the impact such treatment would have on overall function. Antidepressant use did not differ significantly between the transplant eligible and transplant ineligible populations, despite the significantly greater prevalence of mental health symptoms among transplant ineligible patients. Furthermore, linking a specific symptom to a presumed etiology is exceedingly difficult in a patient population with such a high burden of comorbidities and psychosocial stressors. Future research is needed to better understand the impact of aggressive treatment of mental health symptoms in this population and to track resultant functional status malleability.

Transplant eligibility may represent a useful way to explain a portion of the heterogeneity of the ESRD population, and perhaps more meaningfully, could lead to increased awareness in the nephrology community of those HD patients at high risk for symptom burden. In our study, as in clinical practice, transplant eligibility was determined by patients' treating nephrologists. However, while there are published clinical practice guidelines published by transplant physicians,16,17 there are no evidence-based guidelines published by nephrologists that dictate suitability for transplantation referral. While some criteria are likely universal, such as active malignancy, there may be subjectivity when determining how variables such as advanced age (e.g., over 85), cognitive impairment, or depression would affect a patient's transplant eligibility. Studies are needed to assess how variable these determinations are, and further exploration of differences in realms such as prognosis and frailty relative to transplant eligible HD patients will help determine if this would be a worthwhile stratification. If the finding of this study is confirmed, transplant eligibility status may help guide aggressive screening and targeted palliative interventions. Furthermore, identifying patients at high risk for elevated symptom burden may provide the opportunity to modify non-evidence-based treatments that may contribute to symptom burden.

Our preliminary findings highlight the need for more research on symptom management in HD patients regardless of transplant status. Developing effective and practical symptom assessment approaches, ascertaining patients' and care providers' barriers and facilitators to addressing bothersome symptoms, and developing interventions that target these symptoms, as well as determining treatment responses are clearly warranted at this time.18 To our knowledge, this pilot study represents the first attempt at defining a category of HD patients (i.e., transplant ineligibility) at high risk for significant symptom burden.

Our study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Our pilot data were collected from a single institution. The self-reported data were obtained while patients were on dialysis when patients' reflections on overall symptom burden may be influenced. The study also excluded non-English-speaking patients, limiting the extent to which the results can be generalized. Finally, several transplant ineligible patients were too debilitated to participate. While including these patients may not have significantly changed the results, they nonetheless represent an important part of this patient sample.

In conclusion, this pilot study represents the first attempt to identify patients within the HD population at highest risk for substantial symptom burden. Patients who are medically ineligible for transplantation have increased rates of both somatic and emotional symptoms, and may receive substantial benefit from targeted palliative care interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Judy Chan and Beth Hintze for assistance with formatting figures. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (Edward R. Roybal Center for Translational Research on Aging [P30AG022845] Award), the John A. Hartford Foundation (Cornell Center of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine Award), and the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurella M. Covinsky KE. Collins AJ. Chertow GM. Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(3):177–183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansen KL. Chertow GM. Jin C. Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–2967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miskulin D. Bragg-Gresham J. Gillespie BW, et al. Key comorbid conditions that are predictive of survival among hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(11):1818–1826. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00640109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakowski DA. Caillard S. Agodoa LY. Abbott KC. Dementia as a predictor of mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):1000–1005. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00470705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2007. Kidney Diseases: U.S. renal data system…annual data report, researcher's guide, reference tables, ADR slides. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurella Tamura M. Covinsky KE. Chertow GM. Yaffe K. Landefeld CS. McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurella Tamura M. Cohen LM. Should there be an expanded role for palliative care in end-stage renal disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(6):556–560. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833d67bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong DS. Kwok AO. Wong DM. Suen MH. Chen WT. Tse DM. Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23(2):111–119. doi: 10.1177/0269216308101099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtagh FE. Addington-Hall JM. Edmonds PM, et al. Symptoms in advanced renal disease: A cross-sectional survey of symptom prevalence in stage 5 chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(6):1266–1276. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen DJ. Spruit MA. Wouters EF. Schols JM. Daily symptom burden in end-stage chronic organ failure: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2008;22(8):938–948. doi: 10.1177/0269216308096906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsay RM. Heidenheim PA. Nesrallah G. Garg AX. Suri R. Minutes to recovery after a hemodialysis session: A simple health-related quality of life question that is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(5):952–959. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callahan CM. Unverzagt FW. Hui SL. Perkins AJ. Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME. Pompei P. Ales KL. MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel-Kader K. Unruh ML. Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1057–1064. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00430109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins K. Bakris GL. Hypertension goals in advanced-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S92–S94. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04090609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasiske BL. Ramos EL. Gaston RS, et al. The evaluation of renal transplant candidates: Clinical practice guidelines. Patient Care and Education Committee of the American Society of Transplant Physicians. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;6(1):1–34. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinman TI. Becker BN. Frost AE, et al. Guidelines for the referral and management of patients eligible for solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71(9):1189–1204. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura MK. Cohen LM. Should there be an expanded role for palliative care in end-stage renal disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(6):556–560. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833d67bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]