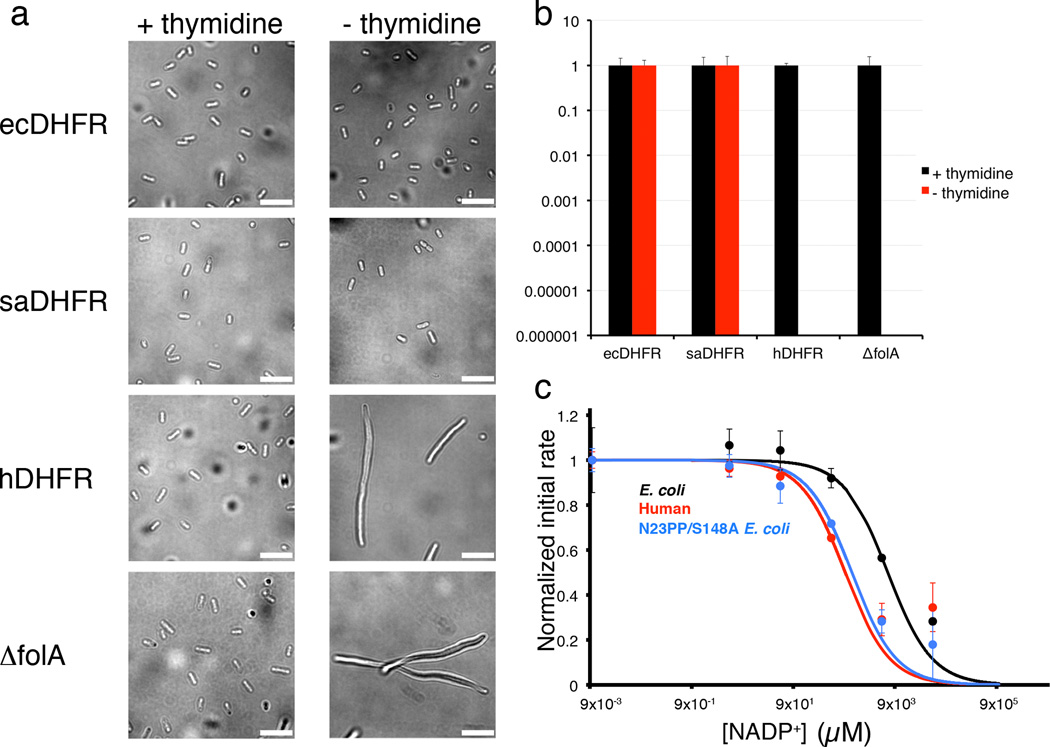

Figure 6. Human DHFR cannot complement DHFR-knockout E. coli cells, and is more sensitive to product inhibition than E. coli DHFR.

(a) DIC micrographs of MG1655 ΔfolA and DHFR knock-in strains temporarily grown with or without thymidine, after initial growth in media supplemented with thymidine. The morphology of MG1655 ΔfolA cells expressing ecDHFR or saDHFR are similar with or without thymidine (short rods). In contrast, MG1655 ΔfolA cells expressing hDHFR filament extensively when grown in the absence of thymidine, similar to the DFHR knockout cell line, MG1655 ΔfolA. The scale bar corresponds to 10 µm. Images were obtained using the open-source microscopy software, µManager36. (b) Relative plating efficiency of MG1655 ΔfolA and DHFR knock-in strains on LB medium with or without 100 µg/mL thymidine. Plating efficiency for each strain on LB with thymidine is normalized to 1. While both ecDHFR and saDHFR restore the ability to grow in the absence of thymidine, hDHFR fails to complement and resembles the folA null mutant, both of which are not viable in the absence of thymidine. The mean plating efficiency (n=3) is reported here, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. c. Initial kinetic rates for ecDHFR (black), hDHFR (red) and E. coli N23PP S148A mutant (blue) enzyme activity plotted as a function of increasing NADP+ concentrations. The IC50 for human DHFR is 948 µM, for ecDHFR, 6518 µM, and for the mutant N23PP S148A ecDHFR 1274 µM, closer to that of hDHFR. The experiment was carried out in duplicate, and values for the mean initial rates are plotted in the figure, with error bars indicating the range of values measured.