Abstract

Castleman disease is most commonly found in the mediastinum, while the head and neck is the second most common location. The disease exists in a unicentric and multicentric variety and is usually successfully treated with surgical resection alone. Early identification is important for treatment planning. Castleman disease has been reported to mimic other disease processes, however there has been only one report of the disease mimicking a nerve sheath tumor in the parapharyngeal space. Here we report the second case of Castleman disease mimicking a schwannoma in the parapharyngeal space.

Keywords: Head and neck, Otolaryngology, Radiology, Schwannoma, Mimicking, Castleman disease, Parapharyngeal space tumor, Lymphoproliferative

Introduction

Castleman disease is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder with unclear pathogenesis [1]. This disease was first described in a single case in 1954 by Dr. Benjamin Castleman [2]. It can present in unicentric or multicentric forms [3], with the unicentric variety usually resulting in a significantly better prognosis [4]. The unicentric process most commonly occurs during the 4th decade of life and is generally successfully treated with surgical resection alone [4–7].

Castleman disease is most often identified in the mediastinum. The head and neck is the second most common location [1–8]. Most lesions are between 5 and 10 cm [4]. Patients with the unicentric variety of the disease often present with an enlarging mass, without other significant symptoms [1].

The differential diagnosis for Castleman disease includes lymphoma, metastatic adenopathy, and diseases that cause adenopathy [9]. To date, there have been three reported cases of Castleman mimicking nerve sheath tumors. Two of these cases were reported in the spine [10, 11], and one was reported in the parapharyngeal space [12].

In this report, we present a 40-year-old female patient who had an enlarged lymph node, diagnosed as Castleman disease, resected from the right parapharyngeal space that mimicked a schwannoma on radiographic imaging.

Case Report

A 40-year-old Asian woman presented with a right-sided parapharyngeal space mass. She reported mild symptoms while swallowing, but not dysphagia. The mass had been initially identified on MRA during a workup for migraine headaches. Examination of the oropharynx demonstrated a right lateral wall mass with a smooth contour, without mucosal involvement. Routine laboratory data and past medical history were both unremarkable.

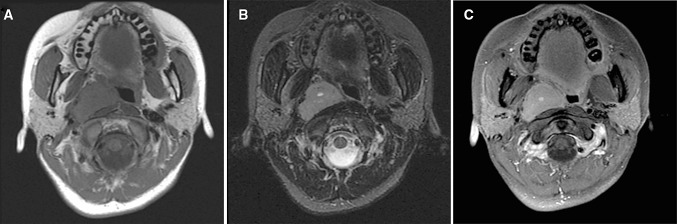

MRI demonstrated a bulky right post styloid parapharyngeal lesion causing lateralization of the right internal carotid artery, extending from the level of the basioccipit of the clivus to the C2/C3 level (Fig. 1). There was a mild mass effect against the right lateral nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal wall and a slight asymmetric soft tissue prominence involving the superior and posterior lateral nasopharyngeal wall. The lesion was mildly hyperintense to skeletal muscle on T1 and T2 weighted series and showed contrast enhancement. There was a 14 mm right IIa and 2 cm right IIb nodal disease. Aside from the size of these lymph nodes there were no other radiographic features to suggest pathologic adenopathy.

Fig. 1.

a–c MRI demonstrating right post styloid parapharyngeal lesion lateralizing the right internal carotid artery extending from the level of the basioccipit of the clivus to C2/C3 level

Surgical resection was performed using a transcervical infratemporal fossa approach to the parapharyngeal space for the removal of the suspected large cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. The intraoperative findings clearly demonstrated a mass that was not arising from either the cervical sympathetic chain or the vagus nerves. Cervical lymph nodes were also excised. Final pathology of the mass revealed the hyaline vascular type of Castleman disease.

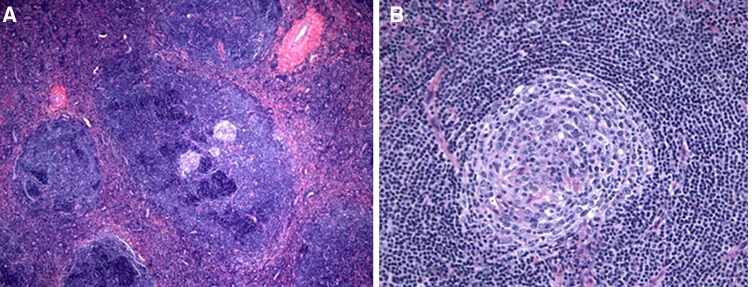

Microscopic examination of the right parapharyngeal lymph node demonstrated a markedly enlarged lymph node with a nodular growth pattern on low power. The sinuses appeared generally intact. High power showed multiple atretic follicles with central hyalinized vessels imitating the follicles. The small mature appearing parafollicular cells were markedly increased in number and focally showed onion-skin type of growth pattern (Fig. 2). No increase in plasma cells was identified.

Fig. 2.

a Lower magnification of the Case 1 showing atretic follicles and several hyalinized vessels with markedly enlarged lymphoid follicles with nodular growth pattern (1a, ×100). b Lymphoid follicle showing para follicular cells were markedly increased in number arranging in onion-skin appearance (1b, ×200)

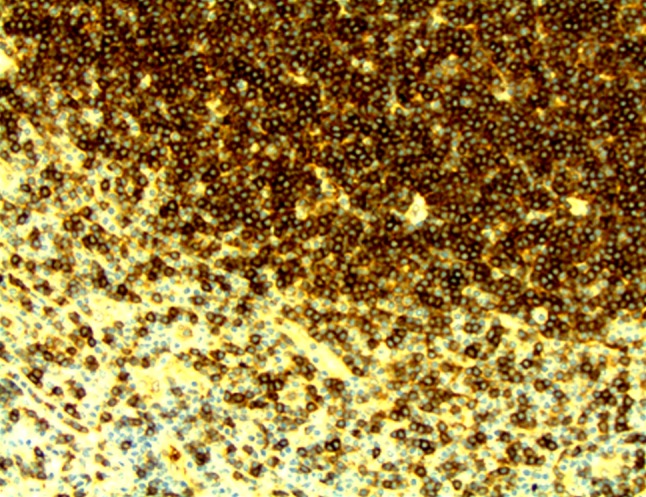

Immunohistochemical stains for CD10, performed to identify remaining atretic germinal centers, were mostly negative. HHV8 staining was negative. IgD showed positivity in the para follicular small lymphoid cells consistent with mantle zone origin. Cyclin-D1 was negative and was used to rule out mantle cell lymphoma (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunostain for IgD showing positivity of the para follicular small lymphoid cells consistent with mantle zone origin The overall morphologic and immunophenotypic features are consistent with Castleman disease (Hyaline vascular type [A1] [A2]) (3, ×350)

The patient had an uneventful post-operative course and continued to do well at her one-month post-operative visit. The tumor was completely excised at the time of surgery and there was no pathologic or radiographic evidence to suggest multicentricity. The patient did not have any comorbid conditions, such as HIV, which is classically associated with the multicentric manifestation of Castleman disease, [13] and no adjuvant treatment was recommended.

Discussion

Unicentric Castleman disease is a rare benign tumor of lymphoid tissue. While it is most commonly referred to as Castleman disease, it may also be referred to as localized nodal hyperplasia, angiomatous, lymphoid hamartoma, giant lymph node hyperplasia, angiofollicular hyperplasia, giant hemolymph node, and follicular lymphoreticuloma [14].

The patient in this report was diagnosed with the hyaline vascular type of the disease, which accounts for 90 % of the histologic variants of Castleman disease [4]. This type of tumor generally presents without symptoms and is most commonly associated with the unicentric form of the disease. This is in contrast to the plasma cell variety, which often causes significant symptoms including fevers, fatigue, night sweats, and weight loss [4].

There has been a known relationship between the multicentric variety of Castleman disease and IL-6 since it was reported by Yoshizaki et al. in 1989 [15–17]. In 2000, Nishimoto et al. were able to successfully improve the clinical course for 7 patients by utilizing an IL-6 receptor antibody to interfere with the signal transduction [18]. The merits of this therapy were further confirmed in a 2005 multicenter prospective study examining the effects of IL-6 interference in 28 patients [19]. In our case, serum IL-6 levels were not ordered because the disease was initially interpreted as a schwannoma.

In the head and neck, the unicentric form of Castleman disease usually presents as an isolated mass of unknown origin. It is characteristically difficult to diagnose on imaging examinations because of its lack of unique signs [9, 20]. Additionally, fine needle aspiration biopsies are often non-diagnostic or incorrectly read as lymphoma due to the presence of lymphoid tissue [21].

The differential diagnosis for a neoplasm in the parapharyngeal space includes salivary gland neoplasms, neoplasms of neurogenic origin, lipoma, lymphoma, sarcoma, and metastatic nodes. In the previously reported case of Castleman disease mimicking a schwannoma in the parapharyngeal space, a 20-year-old man presented with symptoms of dysphagia. His tumor was surgically resected and at 6 months post-operative the dysphagia had diminished and the patient remained disease free [12].

In this particular case, Castleman disease was considered low in the differential diagnosis because imaging showed a right post styloid parapharyngeal space lesion. However because of its rarity, the more likely diagnosis was believed to be a schwannoma arising from the cervical sympathetic chain. The cervical sympathetic chain was considered the more likely nerve of origin due to the direction of displacement of the other carotid sheath structures. Therefore, the differential diagnosis in this case based on radiographic imaging included a retropharyngeal lymph node, paraganglioma, schwannoma, meningioma, or a nodal metastasis. However, following surgical resection, final pathology indicated a diagnosis of the hyaline vascular type of Castleman disease.

In this particular case, the prescribed treatment would not have differed based on the finding of Castleman disease. This is because the preferred treatment for the unicentric variety of this disease is surgical extirpation alone [4, 7, 22]. However, recognizing the true etiology of the parapharyngeal space mass was important when managing post-operative expectations, especially because of the classic relationship between cervical sympathetic schwannoma excision and Horner’s syndrome [23, 24].

To the best of our knowledge, this is only the second reported case of this disease mimicking a schwannoma in the parapharyngeal space. We advise clinicians to recognize the potential for Castleman disease to present as a schwannoma in this anatomical location.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Adrian YY, Becker TS, Rice DH. Giant lymph node hyperplasia of the head and neck (Castleman’s disease): a report of five cases. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck. Surgery. 1995;113(4):462–466. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymph-node hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 2006;9(4):822–830. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195607/08)9:4<822::AID-CNCR2820090430>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flendrig J. Benign giant lymphoma: clinicopathologic correlation study. The year book of cancer. 1970. p. 296–299.

- 4.Dispenzieri A. Castleman disease. Rare hematological malignancies. 2008. p. 293–330.

- 5.Bowne WB, Lewis JJ, Filippa DA, et al. The management of unicentric and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Cancer. 1999;85(3):706–717. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<706::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chronowski GM, Ha CS, Wilder RB, Cabanillas F, Manning J, Cox JD. Treatment of unicentric and multicentric Castleman disease and the role of radiotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92(3):670–676. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<670::AID-CNCR1369>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA. Treatment of Castleman’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2005;6(3):255–266. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yildirim H, Cihangiroglu M, Ozdemir H, Kabaalioglu A, Yekeler H, Kalender O. Castleman’s disease with isolated extensive cervical involvement. Australas Radiol. 2005;49(2):132–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonekamp D, Horton KM, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Castleman disease: the great mimic. Radiographics. 2011;31(6):1793–1807. doi: 10.1148/rg.316115502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn MA, Schmidt MH. Castleman disease of the spine mimicking a nerve sheath tumor. J Neurosurg: Spine. 2007;6(5):455–459. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens EA, Strowd RE, Mott RT, Oaks TE, Wilson JA. Angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia resembling a spinal nerve sheath tumor: a rare case of Castleman’s disease. Spine J: Offici J North Am Spine Soc. 2009;9(9):e18. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karakoc O, Kilic E, Ilica T, Tosun F, Hidir Y. Castleman disease as a giant parapharyngeal mass presenting with dysphagia. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(6):e54. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318231e20f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oksenhendler E, Duarte M, Soulier J, et al. Multicentric Castleman’s disease in HIV infection: a clinical and pathological study of 20 patients. AIDS (Lond, Eng). 1996;10(1):61. [PubMed]

- 14.Ide C, Coene BD, Lawson G, Betsch C, Trigaux J. Castleman’s disease in the neck: MRI. Neuroradiology. 1997;39(7):520–522. doi: 10.1007/s002340050458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng C-H, Chen J-B, Wang J, Wu C–C, Yu Y, Lin T-H. Surgically curable non-iron deficiency microcytic anemia: castleman’s disease. Onkologie. 2011;34(8–9):456–458. doi: 10.1159/000331283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshizaki K, Matsuda T, Nishimoto N, et al. Pathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1989;74(4):1360–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leger-Ravet M, Peuchmaur M, Devergne O, et al. Interleukin-6 gene expression in Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1991;78(11):2923–2930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimoto N, Sasai M, Shima Y, et al. Improvement in Castleman’s disease by humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody therapy. Blood. 2000;95(1):56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimoto N, Kanakura Y, Aozasa K, et al. Humanized anti–interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment of multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2005;106(8):2627–2632. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAdams HP, Rosado-de-Christenson M, Fishback NF, Templeton PA. Castleman disease of the thorax: radiologic features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1998;209(1):221–228. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newlon J, Couch M, Brennan J. Castleman’s disease: three case reports and a review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007;86(7):414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahidi H, Myers JL, Kvale PA. Castleman’s disease. Paper presented at: Mayo clinic proceedings 1995. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Tomita T, Ozawa H, Sakamoto K, Ogawa K, Kameyama K, Fujii M. Diagnosis and management of cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma: a review of 9 cases*. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129(3):324–329. doi: 10.1080/00016480802179735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wax MK, Shiley SG, Robinson JL, Weissman JL. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Laryngoscop. 2004;114(12):2210–2213. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000149460.98629.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]