Abstract

Due to ameliorated surgery as well as better immunosuppression, the recipient age after liver transplantation has been extended over the past years. This study aimed to investigate the health related quality of life after liver transplantation in recipients beyond 60 years of age. The SF-36 was used to evaluate the recipients’ health-related quality of life as standardized tool. It comprises 36 items that are attributed to 8 subscales attributed to 2 components: the physical component score and the mental component score. Differences in the health-related quality of life between the included aged recipients and age-matched general population as well as among female and male recipients. Aged recipients showed significantly lower scores in physical functioning (29 vs. 76, p = 0.001), role physical (42 vs. 73, p = 0.003), bodily pain (34 vs. 71, p = 0.003), general health (28 vs. 59, p = 0.001), vitality (25 vs. 61, p = 0.001), social functioning (36 vs. 87, p = 0.001), role emotional (46 vs. 89, p = 0.001) as well as the physical component score (28 vs. 76, p = 0.001). Aged female recipients showed lower results as compared to males in social functioning, physical functioning, role physical, and social functioning (p = 0.03 respectively) but comparable results in the remaining. Quality of life seems to be an issue among aged recipients and should be assessed on a regular basis.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Immunosuppression, Quality of life, SF-36

Introduction

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is still the treatment of choice for patients suffering from end-stage liver diseases (Mells and Neuberger 2009). Advances in surgical procedures and ameliorated immunosuppressive therapy have led to an extended patient and graft survival (Merion 2010; Wagner et al. 2012). As a result, upper recipient age limits have been increased in the past years, and an older recipient age is not considered as a contraindication any more (Carithers 2000). In the early years of OLT, the upper age limit for recipients did not exceed 55 years (Shaw 1994). Since then, recipient age limits have been extended to over 60 years. In 1990–1991, 10 % of OLT recipients were above 60 years, whereas between 1997 and 1999, 21 % were older than 60 years (Freeman et al. 2007). Similar results after OLT have been reported for elderly patients as for younger recipients (Pirsch et al. 1991; Zettermann et al. 1998). Short-term survival rates after OLT for seniors are comparable to those of younger adults (Levy et al. 2001; Garcia et al. 2001), whereas long-term survival rates are considered to be lower as compared to younger recipients due to complications like malignancies or heart diseases (Cross et al. 2007). Considering these, improving long- and short-term results in the elderly recipient population additional factors like the recipient quality of life after OLT have to be taken into account. Reports on the recipients’ quality of life—especially of the elderly patient population after OLT—are extremely rare. In a large analysis of the liver transplantation database, elderly recipients have been reported to have less patient survival but a similar graft survival and the same quality of life (Zettermann et al. 1998). In this report, all patients were assessed 1 year after OLT. However, while graft outcomes were always important to determine, no results for the quality of life in the long term after OLT exist in the literature up to now.

A fair quality of life is especially important for liver transplant recipients, as one of the aims of a successful liver transplant is to always enhance a patients’ quality of life. Especially in senior recipients who reportedly have a greater perioperative risk and lower long-term survival, a good quality of life is one of the main outcome parameters after OLT.

An excellent way to measure quality of life is to administer the nationally standardized SF-36 (i.e., 36-item short form) questionnaire (Stansfeld et al. 1997; Suzukamo et al. 2001). The SF-36 consists of 8 scales: physical functioning (PF), role limitation due to physical health problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), social functioning (SF), mental health (MH), role limitation due to emotional problems (RE), overall vitality (VT), and general heath perception (GH). Evaluations after transplantation have already been performed with the SF-36 (Humar et al. 2003a).

The presented study aimed to evaluate the quality of life in elderly recipients (i.e., recipients above 60 years of age) in the long term after OLT (i.e., at least 24 months after OLT) as compared to health general population-based results as controls. Additionally, gender-specific differences in the reported quality of life were also assessed between the recipients as well as of gender and age-matched healthy controls.

Patients and methods

Study design

The presented study was carried out as single intervention study at the outpatient ward at the Department of Surgery, Division of Transplantation of the Medical University of Graz. The study was approved by the board of ethics of the Medical University of Graz (ethics committee voting number 23–431, ex. 10/11). Study participants were recruited during their routine control visit at the outpatient ward of the Department of Surgery, Division for Transplantation, where all recipients who received a liver graft at the Medical University of Graz are routinely followed throughout their whole posttransplant period (Kniepeiss et al. 2003).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Patients who were at least 24 months after OLT and above 60 years of age were invited to participate to the presented study. Patients had to have a stable liver function with liver enzymes in the normal range (the preceding 6 months before study entry were analyzed before inclusion) and without accompanying or recurrent diseases. Patients were recruited as described above. All patients gave written informed consent to the presented study.

Patients who did not meet inclusion criteria as well as patients who refused to give consent were excluded from the presented analysis. Patients who had a reported history of depression or psychic diseases or of taking mood-influencing medication were excluded from study participation as well.

Study involvement and processing

After study recruitment, patients underwent their normal routine follow-up visit which includes a blood test and a general health assessment. Both were recorded for the study as well as for the routine patient records. During their study visit, eligible patients were invited to participate to the presented study. Those willing gave their informed consent. The SF-36 questionnaire was handed to them and was filled in by the patients in a quiet separate room.

Study aim

The aim of the presented study was to assess the quality of life in the long term (i.e., after 24 months) after OLT of recipients above 60 years of age as well as to assess potential differences between male and female recipients. All results given by the transplanted patients were compared to age-matched controls.

Health-related quality of life

We evaluated the recipients’ health-related quality of life using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) questionnaire. This questionnaire is a standardized instrument that comprises 36 question items that are scored in 8 subscales: PF, RP, BP, GH, VT, and SF as well as RE and MH. Four of those domains are attributed to the patients’ physical health (role physical, physical functioning, bodily pain, and general health) as well as mental health (role emotional, social functioning, vitality, and mental health). The scales are summarized by three component summary scores: the physical component summary, the mental component summary, and the role/social component summary (Suzukamo et al. 2001). To provide easy compatibility, a norm-based scoring system (NBS) was used to report the results of the SF-36. The raw calculated scores were transformed to NBS scores for each of the mentioned subscales as well as the summary scales with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in the general population.

Selection and rationale of the control population

Scores for the general population as well as for patients with different diseases have been published. To detect and depict differences between the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of aged OLT recipients, their SF-36 scores were compared to published scores of the age-matched general population. It was decided to compare the scoring results to the age-matched general population as published in the manual. The control group population comprised German residents which were included into the norm population for the SF-36 survey by the German government; the characteristics in recruiting those in the control group are as described elsewhere (Suzukamo et al. 2001; Bullinger et al. 2009; Ware et al. 1994; Ellert and Kurth 2004).

Statistical analysis

The SF-36 was analyzed according to the published manual (Suzukamo et al. 2001). First, we assessed the health-related quality of life via the SF-36 and compared the results to the age-matched general population. The whole population, as well as gender-related differences in the health-related quality of life, was assessed. In order to picture the differences between the published norm scores for the SF-36 and the analyzed patient population, z-scores between the patients’ results and the published normative scores have been calculated as described in the manual.

All data are presented as median and interquartile range unless otherwise indicated. All data were checked for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and logarithmically transformed in case of nonlinearity. For between-group comparisons, unpaired Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney U test, or the chi-square test were used accordingly. ANOVA followed by the Fisher’s multiple comparison test was applied to test the differences between groups. Changes in the parameters compared to normalized general population data were analyzed using the Student’s t test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), and a p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study population

In total, 56 patients were included into the presented study. Indications for liver transplantation were mostly alcohol-induced cirrhosis (55 %) and viral hepatitis (40 %) as well as other indications like cystic liver diseases, autoimmune hepatitis, or Budd–Chiari syndrome (5 %). The median age of the included patients was 64 (62; 73). As described above, patients were at least 2 years after OLT. Twenty-nine (54 %) of the analyzed patients were recipients in the short term (until 5 years) after OLT, and 24 (46 %) of the included patients were recipients in their long term after OLT. All included recipients received Mycophenolate Mofetil in combination to other immunosuppressants. Thirty (55 %) of the included patients received Cyclosporine, and 26 (45 %) received Sirolimus as additional immunosuppressant. As gender-specific differences were analyzed as well, included females and males were assessed separately. The characteristics between female and male patients did not differ significantly. All patient characteristics are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compilation of all patient characteristics that were assessed in addition to the presented SF-36 results

| All recipients (n = 56) | Females n = 26 | Males n = 30 | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol induces cirrhosis | 55 %, 31/56 | 62 %, 17/26 | 75 %, 22/30 | n.s. |

| Viral hepatitis | 40 %, 22/56 | 35 %, 8/26 | 17 %, 6/30 | n.s. |

| Other | 5 %, 3/56 | 3 %, 1/26 | 8 %, 2/30 | n.s. |

| Age (a, interquartile range) | 64 (62; 73) | 67 (62; 76) | 65 (60; 74) | n.s. |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 100 %, 56/56 | 100 %, 26/26 | 100 %, 30/30 | n.s. |

| Cyclosporine | 55 %, 31/56 | 46 %, 13/26 | 41 %, 12/30 | n.s. |

| Sirolimus | 45 %, 26/56 | 54 %, 14/26 | 59 %, 18/30 | n.s. |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 36 % (20/56) | 30 %, 8/26 | 40 %, 12/30 | n.s. |

| Divorced | 16 % (9/56) | 15 %, 4/26 | 17 %, 5/30 | n.s. |

| Widowed | 20 % (11/56) | 12 %, 3/26 | 13 %, 8/30 | n.s. |

| Single | 28 % (16/56) | 27 %, 7/26 | 30 %, 9/30 | n.s. |

| Years after transplantation | ||||

| <5 | 54 % (29/56) | 54 %, 14/26 | 50 %, 15/30 | n.s. |

| >5 | 46 % (27/56) | 46 %, 12/26 | 50 %, 15/30 | n.s. |

| Educational level | ||||

| Academics | 16 % (9/56) | 19 %, 5/26 | 3 %, 4/30 | n.s. |

| Higher education | 27 % (15/56) | 23 %, 6/26 | 30 %, 9/30 | n.s. |

| Middle level | 57 % (32/56) | 46 %, 12/26 | 67 %, 20/30 | n.s. |

Health-related quality of life

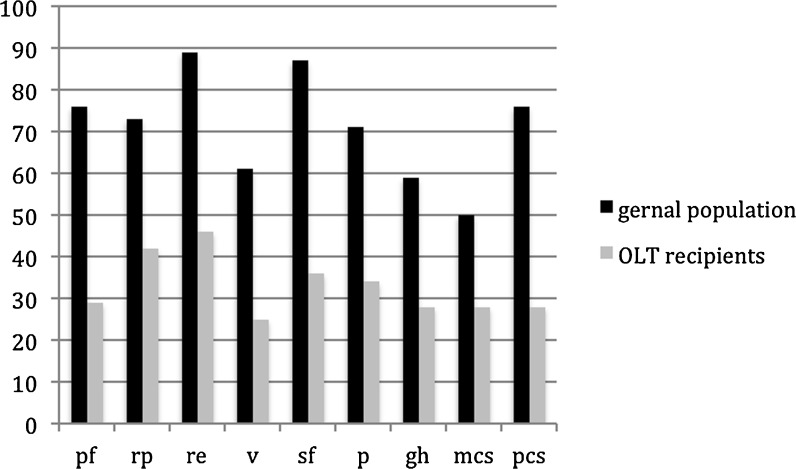

The results of the SF-36 were assessed in the whole patient set as described above and compared to published results for the age-matched general population. Patients after OLT had significantly lower scores in physical functioning (29 vs. 76, p = 0.001), role physical (42 vs. 73, p = 0.003), bodily pain (34 vs. 71, p = 0.003), general health (28 vs. 59, p = 0.001), vitality (25 vs. 61, p = 0.001), social functioning (36 vs. 87, p = 0.001), role emotional (46 vs. 89, p = 0.001) as well as the physical component score (28 vs. 76, p = 0.001) and the mental component score (28 vs. 50, p = 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patients after OLT had significantly lower scores in physical functioning (29 vs. 76, p = 0.001), role physical (42 vs. 73, p = 0.003), bodily pain (34 vs. 71, p = 0.003), general health (28 vs. 59, p = 0.001), vitality (25 vs. 61, p = 0.001), social functioning (36 vs. 87, p = 0.001), role emotional (46 vs. 89, p = 0.001) as well as the physical component score (28 vs. 76, p = 0.001) and the mental component score (28 vs 50, p = 0.001). pf, physical functioning; rp, role physical; re, role emotional; v, vitality; gh, general health; sf, social functioning; bp, bodily pain; mcs, mental component score; pcs, physical component score

Gender-related differences in the health-related quality of life have been assessed between included male and female patients. Aged female recipients reported a significantly lower health-related quality of life in physical functioning (54 vs 68, p = 0.03), role physical (45 vs 53, p = 0.05), vitality (49 vs 48, p = 0.03), and social functioning (71 vs 84, p = 0.03) as compared to the included aged male recipients (Table 2). In all other categories comprised in the SF-36, aged female recipients scored lower as compared to male recipients, but the differences were not significant.

Table 2.

Included recipients were compared to age-matched published controls. Female as well as male recipients reported a significantly lower health-related quality of life as compared to their age-matched controls

| PF | p value | RP | p value | BP | p value | GH | p value | V | p value | SF | p value | RE | p value | PCS | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female recipients | 54 ± 37 | 0.01 | 45 ± 42 | 0.01 | 63 ± 35 | 0.05 | 59 ± 25 | n.s. | 49 ± 27 | 0.03 | 71 ± 36 | 0.03 | 62 ± 49 | 0.01 | 63 ± 22 | 0.03 |

| Female standard | 75 ± 22 | 72 ± 36 | 70 ± 28 | 58 ± 18 | 60 ± 18 | 86 ± 20 | 88 ± 27 | 74 ± 17 | ||||||||

| Male recipients | 68 ± 28 | 0.03 | 53 ± 43 | 0.01 | 75 ± 24 | n.s. | 58 ± 19 | n.s. | 58 ± 19 | 0.03 | 84 ± 22 | n.s. | 68 ± 45 | 0.01 | 68 ± 19 | 0.03 |

| Male standard | 77 ± 23 | 72 ± 34 | 72 ± 26 | 59 ± 18 | 62 ± 19 | 89 ± 17 | 90 ± 25 | 78 ± 16 |

PF physical functioning, RP role physical, BP bodily pain, GH general health, V vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, PCS physical component score

SF-36 results of female as well as male recipients were compared to age- and sex-matched healthy patients. Both aged female and male recipients reported a significantly lower health-related quality of life than the healthy patients (p = 0.05, Table 2).

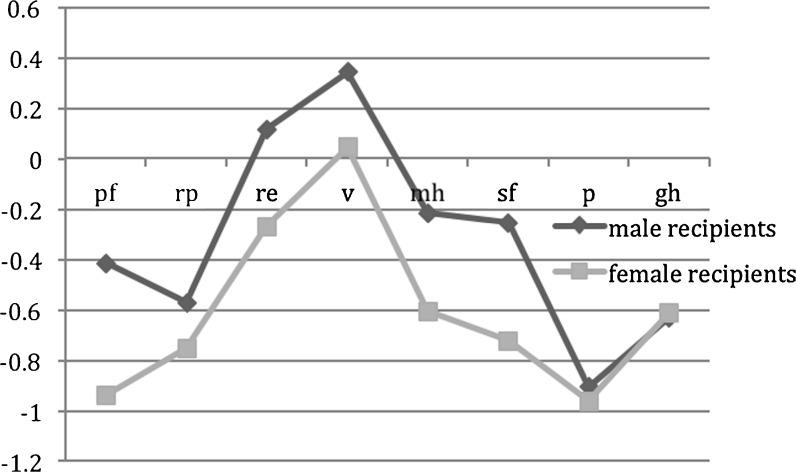

Overall aged female recipients showed a significantly worse quality of life as compared to aged male recipients and as compared amongst and to healthy age-matched subjects (p = 0.05). The differences are expressed as z-scores between aged male recipients and healthy aged-matched subjects and aged female recipients and healthy age-matched subjects. Those differences are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overall female recipients reported a worse health-related quality of life as compared to male recipients as well as compared to age-matched healthy female subjects. pf, physical functioning; rp, role physical; re, role emotional; v, vitality; mh, mental health; gh, general health; sf, social functioning; p, bodily pain

Discussion

Data on the health-related quality of life following solid organ transplantation are very scarce (Kniepiess et al. 2012). Although studies were able to show that patients have a different attitude towards solid organ donation, routine assessments and a psychological follow-up of transplanted patients are still missing widely especially in geriatric patient populations (Stadlbauer et al. 2011; Herrero et al. 2003; Solá et al. 2012).

Therefore, the idea of the presented study was to perform an evaluation of aged patients’ quality of life following orthotopic liver transplantation and relate the given answers to the age-matched healthy population. The presented analysis showed that the HRQOL of patients after liver transplantation among aged recipients differs significantly to that of age-matched healthy patients. This indicated that despite beneficial effects in the HRQOL of patients after OLT have been reported as compared to patients before OLT, recipients’ quality of life still seems to be crucial especially in elderly recipients (Teuber et al. 2008).

The presented results also contradict those gained by studies in patients after renal transplantation, which reported an essential benefit in their HRQOL as compared to dialysis patients (Mujas et al. 2009; Hays et al. 1994). This might be attributed to the fact that patients after renal transplantation do experience the benefit of not having to depend on dialysis anymore, which normally equals a great benefit in their quality of life especially among aged recipients (Beneditti et al. 1994; Humar et al. 2003b; Rebollo et al. 1998).

Health-related quality of life assessments among healthy subjects, as well as patients who suffered from various diseases, revealed that the HRQOL of females usually does not equal those of males in general independent of a prevalent disease (Han et al. 2010; Norris et al. 2004; Ul-Haq et al. 2012). This was observed in the presented study as well. Female recipients after OLT showed the worst quality of life as compared to age-matched healthy female patients as well as compared to male OLT recipients. Similar results after renal transplantation have already been reported where female recipients also tended to have a worse HRQOL as compared to males (Mujas et al. 2009).

Recent reports evaluated HRQOL after living donor-related liver donation, but it seems to be an issue following deceased liver donation as well—especially for elderly recipients (Takada et al. 2012). Despite of low levels of immunosuppression in our presented study cohort, patients reported a low up to middle quality of life. Although these results still represent an improvement to the recipients’ quality of life prior to liver replacement, they do not seem to be as high as they could and should be, especially among septuagenarian female recipients. Stronger evaluation on HRQOL seems to be needed after OLT, and an adjustment of patients’ therapy and therapeutic options might be helpful accordingly. Especially among aged recipients after OLT, the HRQOL is one major factor to achieve successful transplant results; therefore, a stronger concern might be eligible in all but especially in this special recipient cohort.

Footnotes

G. Werkgartner and D. Wagner contributed equally to the presented study.

References

- Beneditti E, Matas AJ, Hakim N, Fasola C, Gillingham K, McHugh L, Najarian JS. Renal transplantation for patients 60 years of age and older. Ann Surg. 1994;220:445–460. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199410000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger M, Kirchberger I, Ware J. The German SF-36 Health Survey. Translation and Testing for the Assess of Qualof Live Zeitschrift für Gesundheitswissenschaften. 2009;3:21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Carithers RL. Liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:122–135. doi: 10.1002/lt.500060122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross TJS, Antoniades CG, Muiesan P, Al-Chalabi T, Aluvihare V, Agarwal K, Postman BC, Rela M, Heaton ND, OÍGardy JG, Heneghan MA. Liver transplantation in patients over 60 and 65 years: an evaluation of long term results and survival. Liver Transplant. 2007;3:1382–1388. doi: 10.1002/lt.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellert U, Kurth BM (2004) Methodological views on the SF-36 summary scores based on the adult German population National Health Survey Germany 47: 1027–32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Freeman JR, Steffig DE, Guiduinger MK, Farmer DG, Berg CL, Merion RM. 2007 SRTR report on the state of transplantation: liver and intestine transplantation in the United States 1996–2007. Am J Transplant. 2007;8:958–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CE, Garcia RFL, Mayer AD, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation in patients over sixty years of age. Transplantation. 2001;72:679–684. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108270-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MK, Swirgris J, Liu L. Gender influences health related quality of life in IPF. Respir Med. 2010;104:724–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Copons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kifney diseae quality of life (KDQL) instrument. Quality Life Res. 1994;3:329–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00451725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero JI, Lucena JF, Quiroga J, Sangro B, Pardo F, Rotellar F, Alvárez-Cienfuegos J, Pietro J. Liver transplant recipients older than 60 years have lower survival and higher incidence of malignancy. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1407–1412. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humar A, Denny R, Matas AJ, Najarian JS. Graft and quality of life outcomes in older recipients of a kidney transplant. Exp and Clin Transplantation. 2003;2:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humar A, Denny R, Matas AJ, Najarian JS. Graft and quality of life outcomes in older recipients of a kidney transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2003;2:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniepeiss D, Iberer F, Gasser B, Schaffellner S, Stadlbauer V, Tscheliessnigg KH. A single center experience with retrograde reperfusion in liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2003;16:730–35. doi: 10.1007/s00147-003-0621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniepiess D, Wagner D, Piennar S, Thaler HW, Porubsky C, Tscheliessnigg KH, Roller RE. Solid organ transplantation: technical progress meets human dignity: a review of the literature considering elderly patients’ health related quality of life following transplantation. Agening Res Rev. 2012;11:181–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MF, Somasundar PS, Jennings JW, Jung GJ, Molmenti GP, Fasola CG, Goldstein RM, GOnwa TA, Klintmann GB. The elderly liver transplant recipient: a call for caution. Ann Surg. 2001;233:107–113. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mells G, Neuberger J. Long term care of the liver allograft recipient. Semin Liv Dis. 2009;29:102–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1192059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merion RM. Current status and future in liver transplantation. Semin Liv Dis Nov. 2010;30(4):411–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujas SK, Story K, Brouillette J, Takano T. Soroka St, Franek C, Mendelssohn D, Finkelstein FO. Health related quality of life in CKD patients correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1293–1301. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05541008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris CM, Ghali WA, Gallbraith PD, Graham MM, Jensen LA, Knudtson ML. APPROACH investiagtors. Women with coronary artery disease report worse health related quality of life outcomes compared to men. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirsch JD, Kalayoglu M, D’Allessandro AM. Orthotopic liver transplantation in patients 60 years of age and older. Transplantation. 1991;51:431–433. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199102000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo P, Ortega F, Baltar JM, Diaz-Corte C, Navascures RA, Naves M, Urena A, Badia X, Alvarez-Ude F, Alvarez-Grande J. Health related quality of life (HRQOL) in end stage renal disease (ERD) patients over 65 years of age. Geriatr Nephrol Urol. 1998;8:85–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1008338802209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BW. Transplantation in the elderly patient. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:389–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solá E, Watson H, Graupera I, Zurón F, Barreto R, Rodriguez E, Pavesi M, Arroyo V, Guevara M, Ginès M, Ginès P. (2012) Factors related to quality of life in patients with cirrhosis and ascites relevance of serum sodium concentration and leg edema. J Hep.epub ahaead of print [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stadlbauer V, Stiegler P, Müller S, Schweiger M, Sereinigg M, Tscheliessnigg KH, Freidl W. Attitude toward xenotransplantation in patients before and after solid organ transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:495–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld SA, Roberts R, Foot SP. Assessing the validity of the SF 36 general health survey in renal transplant patients. Quality Life Res. 1997;6:217–24. doi: 10.1023/A:1026406620756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Green J, Kosinski M, Gandek B, Ware JE. Validation testing of a three component model of Short Form 36 scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;64:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y, Suzukamo Y, Oike F, Egawa H, Morita S, Fukuhara S, Uemoto S, Tanaka K. Long term quality of life of donors after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2012;18:1343–52. doi: 10.1002/lt.23509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuber G, Schafer A, Rimpel J, Paul K, Keicher C, Scheurlen M. Deterioration of health related quality of life and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C: association with demographic factors, inflammatory activity and degree of fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2008;49:923–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ul-Haq Z, Mackay DF, Fenwick E, Pell JP. Impact of metabolic comorbidity on the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: a Scotland-wide cross-sectional study of 5,608 participants. BMC Publ Health. 2012;12:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Kniepeiss D, Stiegler P, Zitta S, Bradatsch A, Robatscher M, Müller H, Meinitzer A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Wirnsberger G, Iberer F, Tscheliessnigg K, Reibnegger G, Rosenkranz AR. The assessment of GFR after orthotopic liver transplantation using Cystatin C and Creatinine based equations. Transplant Int. 2012;25:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 Physical and mental health summary scales: a users manual. Boston: The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zettermann RK, Belle SH, Hoffnagle JH, Lawlor S, Wei Y, Everhart J, Wiesner RH, Lake JR. Age and liver transplantation: a report of the liver transplantation database. Transplantation. 1998;66:500–506. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199808270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]