Abstract

It is encouraging that children with autism show a strong response to early intervention, yet more research is needed for understanding the variability in responsiveness to specialized programs. Treatment predictor variables from 47 teachers and children who were randomized to receive the COMPASS intervention (Ruble et al. in The collaborative model for promoting competence and success for students with ASD. Springer, New York, 2012a) were analyzed. Predictors evaluated against child IEP goal attainment included child, teacher, intervention practice, and implementation practice variables based on an implementation science framework (Dunst and Trivette in J Soc Sci 8:143–148, 2012). Findings revealed one child (engagement), one teacher (exhaustion), two intervention quality (IEP quality for targeted and not targeted elements), and no implementation quality variables accounted for variance in child outcomes when analyzed separately. When the four significant variables were compared against each other in a single regression analysis, IEP quality accounted for one quarter of the variance in child outcomes.

Keywords: Autism, Treatment predictors, Teacher consultation, Goal attainment scaling, COMPASS, Implementation science

Introduction

Although there is strong consensus on the efficacy of early intervention for children with autism (National Research Council (NRC) 2001; Rogers and Vismara 2008), there is also broad acknowledgement that treatment response varies greatly from child to child (McEachin et al. 1993; Sallows and Graupner 2005; Smith et al. 2000). On the one hand, the response to early intervention is encouraging; on the other hand, the variability in responses suggests a need to understand the differences in response to high quality interventions (Stahmer et al. 2010). A particular need is for research on outcomes of children who receive community-based interventions provided by practitioners, rather than research personnel. Most of the children characterized in research reports typically are involved in efficacy studies, and represent those who received high quality, autism specific interventions (i.e., emphasis on early social and communication skills) delivered with intensity (i.e., a minimum of 25 hrs/week; NRC 2001) and often by highly trained personnel-contextual factors that are generally unrepresentative of community based autism intervention services.

The public health concern for access to effective treatments for children with autism is reflected in federal legislation of the Combating Autism Act of 2006 (Pub. Law No. 109–416) and motivates research into possible factors that underlie individual variability in response to treatment. To date, most efforts have focused on physical factors (e.g., child age), neurodevelopmental indicators (e.g., dysmorphic features, head circumference), cognitive-language indicators (e.g., intelligence, receptive and expressive language abilities), social factors (e.g., social abilities, play skills), and autism severity (e.g., symptoms, behaviors) (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2007; Ben-Itzchak and Zachor 2007, 2009; Eikeseth and Eikeseth 2009; Goin-Kochel et al. 2007; Granpeesheh et al. 2009; Perry et al. 2011; Schreibman et al. 2009; Sherer and Schreibman 2005; Smith et al. 2004; Stoelb et al. 2004; Sutera et al. 2007; Szatmari et al. 2003; Turner and Stone 2007; Yoder et al. 2006; Zachor et al. 2007). Other variables reflecting treatment-related factors—e.g., age of diagnosis, age of onset of treatment, and intensity of treatment (Granpeesheh et al. 2009; Perry et al. 2011; Rickards et al. 2007; Turner and Stone 2007) have also been identified as outcome predictors. These latter variables are particularly interesting because they represent contextual factors under the control of public policy administrators, program developers, practitioners, and families. For example, if states or direct service providers make it a priority to identify children early, these efforts should allow children to receive a diagnosis at a younger age and, thus, have the opportunity to access services at a younger age compared to states or agencies without such priorities.

Services for most children with ASD come from one of two sources: the state early intervention system (for children 2 years and younger; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part C, 2004) or the local public school (for children 3 years and older; IDEA, Part B, 2004). Systematic efforts to improve services provided from these two sources can have a broad impact on children and families, especially schools. For almost 40 years, U.S. public schools have been and continue to be the only publically funded provider mandated by federal law to ensure that every child with a disability has access to a free and appropriate public education regardless of family income, insurance status, and geographic location. Further, schools are the primary provider of diagnosis and intervention for children with ASD, in general, and for those who are Black, have young mothers, or have mothers with less education, in particular (Yeargin-Allsopp et al. 2003).

Researchers have identified a critical need to identify mediators and moderators of child educational outcomes (Rogers and Vismara 2008; Stahmer et al. 2010). Despite the enormous role and responsibility of public schools as the primary provider of services for children with disabilities, very little is known about the impact of school-based services on the educational outcomes of children with autism and essentially nothing is known about what conditions are most conducive to promoting educational outcomes for specific students. In particular, of the primary candidate potential mediators of educational outcomes (e.g., use of evidence based practices, teacher training and experience, and program quality), current evidence is largely equivocal, indirect or unsupportive. For example, Hess et al. (2008) surveyed 185 teachers of students with ASD and found that of the five most frequently used teaching methods reported, none had strong scientific support. More recently, Morrier et al. (2011) surveyed 90 teachers on training in autism received and the types of practices used. Training did not correlate with the practices used, and only 5 % of teachers reported using research supported strategies. Although data from both of these studies come from one state (Georgia), they confirm findings from an earlier study conducted in a different state (California). Stahmer et al. (2005) directly interviewed providers of early intervention services and found similar results that practitioners frequently used nonresearch supported practices. Practitioners also reported that they often adapted and used more than one strategy simultaneously based on idiosyncratic decision rules. Moreover, two teacher factors, experience with autism and number of years teaching students with autism, were not associated with the use of evidence based teaching methods (Morrier et al. 2011). Taken together these studies demonstrate the gap in knowledge and how far we are from identifying mediators of educational outcomes.

One issue with much of the prior research has been the lack of a theoretical framework to guide the search for predictors. Accordingly, we offer a framework (see Fig. 1) that considers four predictor domains of treatment outcome: child, teacher, intervention practice quality, and implementation practice quality factors. The latter two domains—intervention and implementation practice quality, are described in Dunst's implementation science framework (2012) and are similar to process variables used in mental health psychotherapy research, because they represent the “actions, experiences, and relatedness” (Orlinsky et al. 2004) between the student and the teacher during instruction. More specifically, implementation practice refers to the methods and procedures used by the implementation agents (i.e., consultant) to promote the interventionist's (i.e., teacher) use of evidence-based practices. Intervention practices include the methods and strategies used by the intervention agents (i.e., teachers) to impact change and produce positive child outcomes. Dunst's and Trivette's framework posits that child outcomes are influenced by intervention practice quality (e.g., what the teacher does with the student) while intervention practice quality is influenced by implementation practice quality (e.g., what the consultant does with the teacher).

Fig. 1.

Tested model of multivariable predictors on child goal attainment outcome

The purpose of this study is to identify the relative importance of these four domains in understanding variability in educational outcomes, as defined by achievement of IEP goals, of children with autism who were randomized into the experimental condition of one of two randomized controlled studies of a manualized parent–teacher consultation implementation intervention called the Collaborative Model for Promoting Competence and Success (COMPASS; Ruble et al. 2012a). COMPASS is a systematic, comprehensive assessment and treatment selection process that is based on the principles of collaboration and shared decision making. It assists in the implementation of evidence based practices by selecting socially valid treatment goals based on an assessment of parent and teacher concerns, the development of measurable teaching objectives, and the generation of personalized teaching plans that are curriculum independent and match the specific needs of the child within the context of the teaching situation (teacher, classroom) and the child's life and family situation. The measurable goals and teaching plans developed as a result of the initial consultation are the focus of the follow-up teacher coaching sessions designed to facilitate teacher implementation of the intervention plans through reflective and supportive feedback. COMPASS has been tested in two separate RCTs (Ruble et al. 2010a, c) and produced large outcome effect sizes relative to control conditions (1.1 for a web-based coaching condition and 1.4 and 1.5 for face-to-face coaching). The current study examines the relationship between and impact on IEP outcomes of child characteristics (i.e., IQ, language ability, adaptive behavior, age, severity, engagement, problem behavior), teacher characteristics (i.e., number of years teaching students with autism, number of students taught, stress, burnout, administrator support), and the process variables of intervention practice quality (i.e., IEP quality, teacher engagement, teacher adherence) and implementation practice quality (i.e., COMPASS fidelity and satisfaction) (see Fig. 1 for the tested model). Analyses were limited to the experimental conditions to allow inclusion of intervention and implementation practice quality when testing all four elements of the model.

Methods

Design and Procedures

The data come from a secondary analysis of combined data from two RCTs of COMPASS, described in detail in Ruble et al. (2012a). The same sampling, recruitment, measures, and randomization procedures were used in both studies. Teachers were special education teachers responsible for the Individual Education Programs (IEP) of students with autism aged 3–8, from public schools located in two Midwestern states.

Each teacher participant was paired with one child with autism selected at random from their class roster. At the start of the school year (Time 1) a comprehensive baseline evaluation was completed for each teacher–child dyad. Table 1 lists the mean scores at baseline of variables included as potential predictor variables. The time 2 evaluation used the same measures and was completed at the end of the school year by an independent evaluator unaware of the child's group assignment.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations between GAS change scores and child, teacher, intervention, and implementation variables for the treatment only group

| Variables | N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. GAS change score | 43 | 7.0 | 2.9 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 47 | 6.0 | 1.7 | .04 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. IQ | 47 | 53.7 | 23.0 | .32* | −.06 | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Language | 47 | 52.8 | 14.5 | .31* | −.24 | .73** | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Severity | 45 | 34.6 | 9.4 | −.41** | .01 | −.41** | −.53** | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Adaptive behavior | 44 | 62.2 | 14.9 | .33* | −.14 | .73** | .75** | −.50** | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Child engagement | 44 | 12.9 | 2.6 | .35* | .06 | .36* | .26 | −.24 | .37* | - | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Problem behavior | 45 | 67.2 | 8.1 | −.08 | .12 | .07 | −.14 | .11 | −.18 | −.15 | - | ||||||||||||||

| Teacher | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Years teaching | 42 | 6.7 | 5.9 | .28 | .14 | −.02 | −.18 | .07 | −.13 | −.17 | .22 | - | |||||||||||||

| 10. Children taught | 42 | 8.7 | 16.1 | .29 | .27 | −.13 | −.21 | −.02 | −.21 | −.01 | −.16 | .27 | - | ||||||||||||

| 11. Stress | 46 | 11.8 | 4.4 | −.30 | −.15 | −.08 | .01 | .10 | −.13 | −.27 | .24 | −.06 | −.19 | - | |||||||||||

| 12. Administrative support | 43 | 3.0 | 0.6 | −.17 | .12 | −.05 | −.20 | .13 | −.01 | .16 | −.10 | −.31 | −.21 | −.19 | - | ||||||||||

| 13. Emotional exhaustion | 47 | 17.4 | 8.9 | −.31* | −.06 | −.03 | −.13 | −.07 | −.07 | −.28 | .14 | −.02 | −.18 | .38** | −38* | - | |||||||||

| 14. Depersonalization | 46 | 2.5 | 3.1 | −.14 | .12 | .12 | .14 | −.22 | .17 | −.14 | .10 | .17 | −.12 | .50** | −.20 | .41* | - | ||||||||

| 15. Personal accomplishments | 47 | 40.2 | 5.8 | .30 | .01 | −.01 | −.06 | .05 | −.03 | .09 | −.28 | −.06 | .21 | −.50** | .26 | −.37* | −.35* | - | |||||||

| Intervention practice quality | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. BL TERS total | 44 | 13.6 | 1.9 | −.20 | .09 | −.07 | −.05 | .27 | −.12 | .11 | −.04 | −.10 | −.10 | −.16 | .18 | .00 | −.12 | .05 | - | ||||||

| 17. IEP NT qualitya | 35 | .80 | .18 | .50** | .18 | .21 | −.11 | −.17 | .10 | .33 | .22 | .03 | .25 | .21 | .03 | .21 | .20 | −.08 | .01 | - | |||||

| 18. IEP targeted quality | 39 | 1.6 | .23 | .51** | −.08 | .27 | .13 | −.20 | .26 | .32* | −.13 | .16 | −.06 | −.19 | .24 | −.42** | −.15 | .23 | .16 | .32 | - | ||||

| 19. Teacher adherence | 43 | 4.3 | 1.2 | .40** | −.04 | −.06 | −.03 | −.01 | −.16 | .02 | −.01 | .15 | .14 | −.20 | .01 | −.32* | −.18 | .11 | −.25 | −.03 | .26 | - | |||

| Implementation practice quality | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20. COMPASS satisfaction | 42 | 3.6 | .44 | −.15 | −.10 | −.34* | −.40** | .29 | −.31* | −.04 | −.22 | .03 | −.05 | −.07 | .15 | .11 | −.35* | −.11 | .13 | −.11 | .13 | .09 | - | ||

| 21. Coaching satisfaction | 43 | 3.2 | .56 | −.07 | .14 | −.49** | −.46** | .41** | −.44** | .15 | −.08 | .05 | .03 | −.13 | .23 | −.27 | −.38* | .14 | 49** | −.01 | .10 | .09 | .29 | - | |

| 22. COMPASS fidelity | 36 | .89 | .16 | .11 | −.28 | −.20 | −.05 | .11 | .10 | .22 | −.04 | −.09 | −.11 | .04 | .05 | −.21 | −.13 | −.22 | −.37* | −.10 | .12 | .33* | .20 | .04 | - |

Two-tailed,

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01

NT = not targeted in COMPASS

Randomization to group assignment occurred following the Time 1 assessment. For both studies, teachers in the experimental conditions received the initial COMPASS consultation and four follow-up coaching sessions. The initial consultation included the teacher and parent and lasted approximately 2.5–3 h. Each coaching session lasted between 60 and 90 min and occurred about every 4–6 weeks. For the first RCT, the dyad was randomized to face-to-face (FF) COMPASS (initial consultation and coaching were face-to-face), or to a comparison group consisting of services as usual. For the second RCT, the dyad was randomized to one of three groups: FF COMPASS, web based (WEB) COMPASS (initial consultation was face-to-face but the coaching was provided by web based videoconferencing), or to a comparison group, which received additional online professional development training in three teaching methods in autism (structured teaching, peer mediated training, and picture exchange communication system) provided to the public at no charge (http://www.autisminternetmodules.org/). This training was considered a placebo because research shows that didactic information provided alone does not result in changes in teacher behavior (Trivette et al. 2009); results from our RCTs verified this result (Ruble et al. 2010a, 2012a, b, 2013).

Description of COMPASS

COMPASS consists of two parts, the initial consultation conducted near the beginning of the school year and four follow-up coaching sessions every 4–6 weeks throughout the school year. The initial consultation involved detailed sharing of parent and teacher descriptions of the child's self-management, interfering behaviors, social, communication, sensory, and independent learning skills. Areas of concern were noted and the remaining time was spent identifying three target goals for instruction throughout the remainder of the school year. During each coaching session, the consultant met with the teacher and reviewed a videotape of the teacher implementing the teaching plan with the student and compared the written teaching plan to the videotaped instruction. Teachers were asked to reflect on what they observed and describe what worked well and what they would change. The goal attainment scale was then used to monitor student progress. A brief structured interview also was completed that asked the teacher to describe how often the skill was taught, who worked on the skill with the student, and whether data were being kept on progress. A written report was then provided within 1 week to the teacher that summarized the coaching session and provided recommendations to be implemented until the next coaching session. At the end of the school year, an observer who was independent of the research team conducted final direct observations of the child's level of progress using the goal attainment scale.

Participants

Thirty-five special education teachers and one student with autism selected randomly from each class (N = 35) participated in study one; 18 teachers in the experimental group and 17 teachers in the control group. For study 2, a total of 44 special education teacher–student with autism dyads (N = 44) participated; 15 teachers in the comparison condition and 29 teachers in the experimental conditions (15 in the FF condition, and 14 in the WEB condition). For both studies, the diagnosis of autism was confirmed with the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, a semi-structured assessment tool (Lord et al. 2000). Data from the total of 47 experimental group participants who completed the two studies were used for this secondary analysis.

Measures

Child Variables

Child Educational Outcome

The primary time 2 child outcome was the degree of progress made toward three targeted IEP objectives rated by an independent observer. IEP objectives were developed during the COMPASS consultation. Table 2 provides a sample list of several IEP objectives. To ensure goal comparability and that goals focused on critical areas of intervention for those with autism (NRC 2001), a social skill, a communication skill, and a learning skill were either developed or selected from all IEPs at time 1. Teachers were asked to demonstrate for the evaluator, at baseline and at post-treatment, the child's current level of progress on each of the three targeted teaching objectives during a curriculum based instructional situation which typically lasted 20 min and was videotaped.

Table 2.

Sample of IEP goals

| Social skills |

| Imitate actions with 5 different objects with a peer and with peer prompts 5 times with each object each day over a 2 week period |

| Engage in 6 different turn-taking activities initiated by a peer for 10 min with peer prompts only—each activity reaching criteria four times–at least twice a week |

| Take turns with at least one peer using objects for two exchanges with visual and peer prompts only and saying “your turn” once daily for 2 weeks |

| Follow group rules of turn taking while waiting his turn in line at the cafeteria or at recess and waiting to be called on during math for 1 min independently and without calling out or cutting in line to be in the front 2 times per day for 2 weeks |

| Imitate adult play activities with at least 3 different preferred objects (dinosaurs, animals, doll…) each day across 2 weeks |

| Communication skills |

| Will initiate a request by pointing to or exchanging a picture/object with a peer or adult with 80 % accuracy over 3 consecutive sessions with 2 verbal/gestural cues for each |

| Will engage in conversational turn-taking through 4 turns (back and forth as 1 turn) with peer(s) and in a structured group, staying on topic with visual prompts 4 of 5 opportunities in a 1 week period |

| Will give full sentence answers when asked about his specific past experiences that day for 3 exchanges on 3 topics a day for 5 consecutive days |

| During a structured play activity with a peer, will make 5 appropriate comments during 5 activities within 1 week |

| Will make 10 different requests per day independently (go home, eat, help, more, finished, various objects/activities) using sign, pictures, or verbal on a daily basis |

| Work skills |

| Will follow 1–2 step directions with no negative feedback (aggressive behaviors) 80 % of the time on three out of five monitored sessions with 2 verbal/gestural cues |

| He will complete an independent familiar work task when presented with a model with one verbal prompt once a day for 2 weeks |

| Will follow a relaxation routine with 2 verbal cues and visual cues and be able to continue in the current activity or setting without escalating behaviors (whining, yelling out) on 5 consecutive occasions when he is starting to be upset/anxious |

| When given a familiar task, He will start the task with one specific cue from an adult, visual cues, and no more than 2 adult verbal or gestural cues to complete the task with an adult more than 5 feet away from him 4/5 opportunities for 2 weeks |

| When presented with a task menu from which to select a work task, will start and complete three 2–3 min tasks each day without aggression with adult verbal cues across 2 weeks |

Psychometric equivalence tested goal attainment scaling (PET-GAS) was used as the measurement system for progress monitoring (Cytrynbaum et al. 1979; Oren and Ogletree 2000; Ruble et al. 2012b). PET-GAS is ideal as an idiographic measurement approach when treatment outcomes, treatment plans, and starting baseline levels differ from child to child. We conducted a series of studies to ensure and assess the interobserver reliability and the stability of PET-GAS scores produced using our data collection methods (i.e., behavior samples collected by the teacher vs. researcher and from videotape vs. live observation). We also tested PET-GAS templates to ensure comparability between groups (comparison vs. treatment) across three dimensions (a) objectivity of goals, (b) equivalence of intervals used to score the goal, and (c) equivalence of difficulty levels associated with accomplishing the goal. We were able to confirm group comparability (experimental vs. control) on the PET-GAS across the three dimensions and across data collector and observation methods when systematic procedures were carefully applied to the creating of the PET-GAS template and the scaling of the benchmarks. Details are discussed in Ruble et al. (2012b) and in Ruble et al. (2012a). We also confirmed that there was no association between blind, independent ratings of level of difficulty of the goals and child goal attainment outcome for the experimental group participants using Pearson correlation (r = .003, p = .99). In other words, child variance in goal attainment outcome was not explained by difficulty level of the goal.

A 5-point scale was used to measure progress: −2 = child's present levels of performance, −1 = progress, 0 = expected level of outcome, +1 = somewhat more than expected, +2 = much more than expected. Thus, a score of zero represented improvement consistent with the actual description of the written IEP objective. To ensure objective and direct measurement of skills, time 2 PET-GAS ratings were based on observations by an independent observer who was unaware of child group assignment. Excellent inter-rater reliability was achieved for both study 1 (ICC = .99) and study 2 (ICC = .90). Change scores were calculated based on progress from the beginning to the end of the school year.

Intellectual Ability

The Differential Abilities Scale (DAS; Elliott 1990) was chosen as the cognitive measure because it can be administered to young children. The General Conceptual Ability (GCA) subscore was used to measure overall cognitive ability. The internal consistency of the GCA across ages ranges from .89 to .95 for the Preschool Level and from .95 to .96 for the School-age level. The test–retest reliability of the GCA for both age levels ranges from .89 to .95 (Elliott 1990).

Language Ability

Language was assessed with the Oral and Written Language Scales (OWLS; Carrow-Woolfolk 1995). The OWLS is an assessment of receptive and expressive language for children between 3 and 21 years, and consists of three scales: Listening Comprehension, Oral Expression, and Written Expression. Internal consistency ranges from .84 to .93, and test–retest reliability ranges from .73 to .90 (Carrow-Woolfolk 1995).

Autism Severity

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al. 1980) is a 15-item observational scale designed to evaluate the severity of autism along several dimensions (e.g., social relating, resistance to change, communication). A 4-point scale is used to rate degree of abnormality. Total score test–retest reliability is .88 and the correlation between the CARS and clinical ratings of autism is .84 (Schopler et al. 1980).

Adaptive Behavior

Adaptive behavior was measured by teacher report using the Classroom Edition of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS; Sparrow and Cicchetti 1995). The VABS is a standardized tool that allows for the measurement of classroom adaptive behavior. Four domains were evaluated: socialization, communication, daily living skills, and motor skills. The coefficient alpha for the Adaptive Behavior Composite is .98.

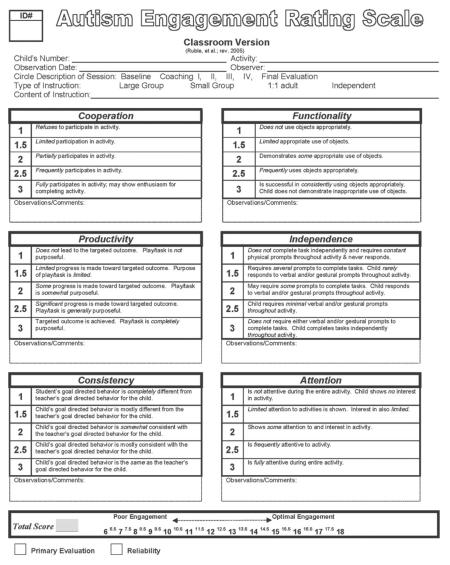

Child Engagement

The Autism Engagement Scale (AES) is an author generated observation measure of global child engagement originally developed for use in an outpatient treatment program for children with autism and their caregivers. It assesses the overall global quality of the child's interaction with a targeted adult along six dimensions of child behavior during an activity: (a) cooperation; (b) functional use of objects; (c) productivity; (d) independence; (e) consistency between the child's and the teacher's goals; and (f) attention to the activity. Items are rated using a 5-point, Likert scale ranging from 1 to 3, with −0.5 midpoints and complements the Social Interaction Rating Scale, described below (SIRS; Ruble et al. 2008). The items are summed to provide a total score. Higher scores reflect better engagement. Two of the items on the AES (cooperation and goal consistency) were derived from an earlier study of the quality of engagement of students with autism compared to students with Down Syndrome. An analysis of 711 samples of naturalistic behaviors called activity units were coded for quality of engagement (Ruble and Robson 2007); students with autism showed higher cooperation and less goal consistency compared to those with Down syndrome. Exploratory factor analyses using principal components analysis was conducted to determine whether the six engagement items formed a unidimensional scale or subscales. With respect to the six items, the scree plot of eigenvalues indicated a one-factor solution and only one component was extracted. Moreover, internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .86) was highest when all six engagement items were treated as a single dimension. Accordingly, the items were summed to form the single scale. A copy of the instrument with definitions is provided in the “Appendix”. At the start of the school year, two raters independently coded 52.7 % of the observations immediately following observation of the student–teacher instructional situation. Internal consistency (alpha) was 0.92, and interobserver reliability based on total scores from the independent observers was good [r = 0.88, p = .000, two-tailed].

Maladaptive Externalizing Behavior

Externalizing behavior was rated by the teacher using the Behavior Assessment System for Children Second Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). The BASC-2 is a multimethod, multidimensional system used to evaluate behavior of children and young adults aged 2 through 25 years. Internal consistency (alpha) for domain scores relevant to the externalizing problems composite range from .94 to .97 and test–retest reliabilities range from .78 to .91. A coefficient alpha of .82 was obtained in the current sample for the three subscales (hyperactivity, aggression, and conduct problems) that make up the externalizing problems composite.

Teacher Variables

Years Teaching, Number of Children Taught, and Administrative Support

Teachers completed a background questionnaire that asked open-ended questions for number of years teaching children with autism and the number of children taught. Eleven additional questions asked teachers to rate how much support they received from school administration using a 4-point Likert Scale (1 `not much support,' 4 `very much support'). Internal consistency (alpha) for the 11 questions on the support subscale was adequate (alpha = .87) using the combined sample.

Teacher Stress

The Index of Teaching Stress (ITS; Greene et al. 1997, 2002) quantifies teachers' stress in response to a specific student. The ITS consists of two global scales—student characteristics and teacher characteristics. For this study only Part B, teacher characteristics was used. Part B is comprised of 43 items that are rated on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 “never distressing” to 5 “very distressing” and includes four subscales: Self Doubt/Needs Support, Loss of Satisfaction from Teaching, Disrupts Teaching Process, and Frustration Working with Parents. In the original standardization sample internal consistency (α) for the total scale was .96 (Greene et al. 1997, 2002). The alphas for the teacher domain subscales ranged from .95 to .84.

Teacher Burnout

The 22-item MBI Educators Survey (Maslach et al. 1996) was used to assess three components of teacher burnout: emotional exhaustion (EE; i.e. feelings of being overextended, both emotionally and physically), depersonalization (D; i.e., characterized by negative, cynical attitudes and feelings), and reduced personal accomplishment (PA; i.e., negative evaluation of self, particularly in relation to job performance). Items are rated using a 7-point scale (ranging from 0, “never” to 6, “every day”). Reliability coefficients for the three subscales are adequate to good: ranging from .90 to .71 (Maslach et al. 1996).

Intervention Practice Quality

IEP Quality

One goal of COMPASS is the generation of three personalized and measurable objectives that are then incorporated into an updated IEP. To measure the expected improvement in IEP quality, a rating scale assessment was developed using standards from the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) and best practices from the National Research Council (NRC) for educating students with autism (2001; Ruble et al. 2010b). The IEP assessment can be used to measure quality improvement in targeted areas (e.g., goals targeted and thus expected to change following the initial COMPASS consultation) and non-targeted areas (IEP elements not targeted and thus not expected to change following COMPASS). To measure change in targeted IEP goals, each of the three objectives is rated for (a) the degree to which it was described in behavioral terms, (b) how well the conditions under which the behavior was expected to occur were specified, and (c) how well the criterion or objective acquisition was explicitly described using a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 = no/not at all evident, 1 = somewhat evident, 2 = yes/clearly evident). Three additional questions ask the degree to which communication, social, and independence objectives are present on the IEPs. An overall mean item score is calculated. Interrater agreement for the targeted IEP quality measure was adequate as assessed using the intraclass correlation (ICC = .79; Ruble et al. 2010a, b).

As mentioned above, we also measured additional quality indicators not targeted by COMPASS but still important because they reflected the recommended elements outlined in IDEA and NRC (fora copy of the complete measure,see Ruble et al. 2010a, b). To measure non-targeted IEP quality, four IDEA and seven NRC quality indicators were evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale (0 = no/not at all; 1 = somewhat; 2 = yes/clearly evident). The IDEA indicators included the description of: (a) the student's present level of performance for the goal; (b) the link between the student's performance of the objective and the general or developmental curriculum; (c) the method of goal measurement; and (d) the individualization of the specially designed instruction associated with the goal/objective were evaluated. The NRC indicators included the description of: (a) parental concerns; (b) goals that reflected (1) engagement in tasks or play which were developmentally appropriate, and included appropriate motivational systems; (2) fine and gross motor skills; (3) basic cognitive and academic thinking skills; (4) replacement of problem behaviors with appropriate behaviors; and (c) a recommendation for extended school year were evaluated. An overall mean score for IEP non-targeted quality was calculated. Higher mean scores reflected better adherence to IDEA and NRC.

Teacher Engagement

The Social Interaction Rating Scale for Autism (SIRS; Ruble et al. 2008) is a global observation measure of the quality of the interaction between the student and the teacher, with a focus on teacher behavior. Item and subscale scoring parallel the AES. SIRS assesses six dimensions of teacher behavior during an instructional interaction with the student: (a) level of affect; (b) maintenance of interaction; (c) directedness; (d) responsiveness; (e) initiation, and (f) level of movement with regard to the child. Items are rated using a 5-point, Likert scale ranging from 1 to 3, with −0.5 midpoints. The items are summed to provide a total score. Internal consistency (α) was .89, and interobserver reliability using intraclass correlation was 0.94.

Teacher Adherence

The consultant completed a one-item adherence rating immediately following each coaching session for a total of four data points. The single item measure rated the degree to which the teacher was following the teaching plan recommendations using a 5-point Likert-type rating scale (1 = not at all or 0 %, 2 = about 25 %, 3 = about 50 %, 4 = about 75 %, 5 = very much or 100 %). To assess interrater agreement, raters independently rated the adherence item immediately following 80 % of the coaching sessions. The interrater agreement was good, Cohen's κ = .90. The mean score for the four sessions was used in the analysis.

Implementation Practice Quality

COMPASS Fidelity

The COMPASS Fidelity Survey evaluated the extent to which critical aspects of the consultation were implemented. The Fidelity Survey is a 25-item close-ended (yes/no) checklist completed by teachers immediately following a consultation. Internal consistency estimate (α) was .96.

COMPASS Satisfaction

Both teachers and caregivers completed a 25-item questionnaire to assess satisfaction. Items were rated using a 4-point response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Sample items include: I felt involved during the consultation and able to express my views; the consultant's communication skills were effective; and the consultant was knowledgeable about autism. Internal consistency (α) was .92 for teachers and .90 for parents.

Coaching Satisfaction

The 10-item Coaching Feedback Form measured helpfulness of the coaching sessions and was administered at the end of the school year. Each question is rated on a 4-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Eight items measured positive aspects of the coaching sessions (e.g., session supported you in helping the child reach his IEP goals; supported you in implementing strategies to reach three targeted objectives) and two items measured potential negative aspects of coaching (e.g., how much did the coaching sessions cause you stress.). Internal consistency (α) for the total scale was .82.

Data Analysis Plan

Both bivariate and multivariate analyses were used to determine general predictors of child outcomes within the experimental group. Bivariately, we used Pearson correlation to explore the relationship between the child goal attainment change scores and the following potential time 1 predictor variables: (1) seven child variables (age; IQ; language; autism severity; adaptive behavior; engagement with teacher; problem behavior), (2) seven teacher variables (years teaching autism; number of children taught; stress related to child; administrator support; burnout measured by exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishments), (3) four intervention quality variables (teacher engagement; IEP quality targeted with COMPASS; IEP quality not targeted with COMPASS; teacher adherence), and (4) three implementation quality variables (COMPASS fidelity, teacher satisfaction with the initial consultation, teacher satisfaction with coaching sessions).

Multivariately, we conducted independent stepwise regression analyses predicting change in GAS scores separately for the child, teacher, intervention quality, and implementation quality predictor variables. All predictor variables significant with child outcomes were selected for inclusion in the regressions. Next we conducted a final regression analysis that examined the relative contributions of the variables identified as significant in the separate predictor analyses.

Results

Intercorrelations Between Predictors

There were significant correlations between many of the child variables in the directions one would expect. Autism severity was negatively associated with cognitive, language, and adaptive behavior skills (see Table 1). Not surprisingly, cognitive, language, and adaptive behavior skills were also positively associated with one another. In addition, the quality of the child's engagement during instruction was positively associated with both cognitive ability and adaptive behavior. In contrast, child age and problem behavior were not associated with any of the child variables.

Several teacher variables were associated with each other. Teacher stress was associated with all three measures of burnout—positively with exhaustion and depersonalization, and negatively with accomplishment. One teacher burnout variable—emotional exhaustion—was negatively associated with administrator support. The burnout measures were associated with one another in expected directions.

Of the intervention practice quality variables, IEP targeted quality was positively associated with child engagement. IEP targeted quality and teacher adherence were negatively associated with teacher emotional exhaustion.

Of the implementation practice quality variables, teacher satisfaction with the initial consultation and followup coaching sessions was negatively associated with several child measures of IQ, language, and adaptive behavior. Further, satisfaction with coaching sessions was positively associated with autism severity. Teacher depersonalization was negatively associated with satisfaction with both the initial consultation and coaching sessions. Teacher engagement was positively associated with coaching satisfaction and negatively associated with consultant fidelity. Lastly, consultant fidelity was positively associated with the intervention practice variable teacher adherence.

Bivariate Predictors of Improvement in Child's Goal Attainment

Nine of the 20 potential predictors were associated with child goal attainment change scores. For child predictors, goal attainment change score was negatively associated with autism severity and positively associated with IQ, language, adaptive behavior, and engagement (see Table 1). One teacher predictor variable, emotional exhaustion, was negatively associated with GAS change scores. Two other variables, stress and personal accomplishments, correlated with GAS change scores at a trend level, p levels of .054 and .052, respectively. Finally, GAS change was positively associated with three intervention quality variables—IEP quality targeted by COMPASS, IEP quality not targeted by COMPASS, and teacher adherence. None of the implementation quality variables predicted child outcome.

Multivariate Predictors of Improvement in Goal Attainment

Predictors for each of the four areas (child, teacher, intervention quality, and implementation quality) were examined independently using regression analysis. For the child variables, of the five variables entered into the model, only one variable, child engagement, was a significant independent predictor of goal attainment outcome, accounting for 22.1 % of the variance (R2 = .221, F(1, 36) = 10.1, p = .003; see Table 3). Similarly, for the teacher variables, emotional exhaustion was a significant independent predictor of child goal attainment outcome, accounting for 9.3 % of the variance (R2 = .093, F(1, 40) = 4.1, p = .05). For the three intervention quality variables entered into the regression, both IEP quality variables predicted child goal attainment outcome, accounting for a total of 34.7 % of the variance (R2 = .347, F(2, 29) = 7.7, p = .002). Lastly, the regression examining implementation quality predictors was not conducted, because none of the predictors were associated bivariately with child goal attainment outcome.

Table 3.

Summary of regression analysis for pretreatment variables predicting child goal attainment change scores

| Variables | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Engagement | .53 | .16 | .47 |

| Teacher | |||

| Emotional exhaustion | −.10 | .05 | −.31 |

| Intervention quality | |||

| IEP not targeted quality | 5.2 | 2.3 | .37 |

| IEP targeted quality | 4.0 | 1.9 | .34 |

The final stepwise regression analysis combined the four significant predictor variables from the individual regression analyses together: child engagement, emotional exhaustion, and IEP quality to determine the relative contribution of each variable. Nontargeted IEP quality was the only significant independent predictor accounting for 25 % of the variance (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Prediction by child and intervention practice quality variables of child goal attainment outcome

| Hierarchical step | Variable | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IEP not targeted quality | .25 | .25 | 9.4 | .005 |

Discussion

This exploratory study analyzed treatment response to a parent–teacher collaborative consultation, treatment planning and treatment implementation intervention. Four types of treatment predictor variables were examined: (a) child, (b) teacher, (c) intervention practice quality (what the teacher does with the student), and (d) implementation practice quality (what the consultant does with the teacher; see Fig. 1). The child predictors of IEP goal attainment outcome replicated results found in several prior studies of predictors of general treatment outcomes. Specifically, higher IQ, better receptive and expressive language, increased adaptive behavior, and decreased autism severity all were significant predictors of positive changes in child outcome. That is, several of the broad indicators associated with autism and intellectual disability impacted children's responses to the consultation intervention. More interestingly, however, a new variable emerged, child engagement, that also predicted outcome. Engagement is potentially important as a predictor because it indexes classroom behaviors representative of how students learn generally.

Analysis of the predictors multivariately revealed a slightly different picture. When all child variables were examined in the regression, only child engagement emerged as a significant independent predictor of outcome. This finding was unexpected because IQ, language, and autism severity have been identified in numerous studies as pretreatment predictors of outcome. This suggests that the impact that these other more typically measured child variables have on outcomes may be produced, at least in part, through their influence on engagement. Importantly, unlike IQ or severity, the construct of engagement, as measured in this study, represents child behaviors that can be influenced by the environment. Further, engagement is considered an active ingredient of effective early intervention programs (NRC 2001) and the amount of engaged time is associated with child response to treatment programs (NRC 2001). Thus, these findings provide potentially interesting new information on the relative importance of traditional child variables and suggest that child engagement, which may be a more malleable variable due to its assumed influence from the environment, plays an important role in how children responded to the COMPASS intervention. That the quality of the child's engagement as assessed during an instructional activity may be more important than child factors like IQ, language, and severity, which may be less flexible—especially for older students, is a novel and important finding that needs to be replicated in future research. However, because the engagement measure is unvalidated, these results should be interpreted with caution and require replication, perhaps including other measures that tap similar dimensions.

The analysis of the teacher variables bivariately produced both expected and surprising results. Similar to a prior study that found no relationship between teacher experience and use of evidence based teaching strategies (Morrier et al. 2011), number of years teaching students with autism and number of students taught were both unrelated to child outcomes. In contrast, teacher burnout, as measured by emotional exhaustion was related to child goal attainment change. Students whose teachers reported greater burnout at the start of the school year made less improvement in child goal attainment measured at the end of the school year. It should be noted, however, that virtually identical bivariate correlations were found for the stress scale and the personal accomplishments burnout subscale (.30 and .31), such that the correlations just missed being significant with child change in goal attainment.

These findings are important because they suggest that burnout is a potential teacher risk factor that could be identified early in the consulting relationship. Moreover, the interactive impact of an environmental risk factor, such as teacher burnout or poor adherence, together with increased child personal risk factors, such as limited cognitive and verbal skills, could place the student at a significant disadvantage for making progress during the school year. More practically, these data suggest that a teacher experiencing stress and fatigue should be provided with additional supports. Such supports can take many forms. For example, we found a negative association between administrator support and emotional exhaustion, a finding noted by others (Zabel and Zabel 2002). Thus, programs that foster increased administrator support for teachers may be helpful to buffer the effects of stress and burnout associated with teaching children with complex learning needs such as those with ASD. Another important implication of these findings is that the child should be considered within an ecological context (e.g., teaching situation) when evaluating predictors of child outcome. These findings validate the need for ecological interventions that consider both the features of the child and the internal experiences of the adults who are responsible for teaching the children.

Intervention practice quality was modeled by teacher engagement, teacher adherence, and two measures of IEP quality: (a) targeted IEP quality, reflecting items expected to change as a result of COMPASS and (b) non-targeted IEP quality, reflecting IEP elements which were not a target of COMPASS, but still indicative of quality. Adherence and both IEP quality measures were significant predictors of child outcomes bivariately. Teacher adherence was also positively associated with COMPASS fidelity, consistent with Dunst and Trivette's (2012) framework positing a relationship between implementation practice and intervention practice. However, when the three significant intervention practice variables were analyzed multivariately, only the IEP non-targeted measure was a significant predictor, accounting for a quarter of the variance in child outcome. Our targeted measure of IEP quality is based on whether the child's educational plan, as revised after the initial COMPASS consultation, included measurable goals that can be monitored over time and whether social, communication, and learning skills goals are included in the plan. That is, targeted IEP quality indexes the direct impact of COMPASS on improving IEPs. In contrast, non-targeted IEP quality, which was not expected to change as a result of the COMPASS intervention, likely indexes pre-existing teacher skill in crafting IEPs. Thus, one measure indexes improvements in IEP quality associated with implementation of COMPASS and one indexes natural variation in teacher skills in writing and conceptualizing an individualized teaching program. Moreover, pre-existing teacher skills appear to independently impact quality of the IEP, which in turn was strongly related to outcomes.

Importantly, IEP quality is a potentially controllable aspect of the intervention that, if maximized, could make a meaningful impact on overall outcome. Moreover, IEP quality is not unique to the COMPASS intervention and is a variable that underlies all special education programming, That is, it is plausible that IEP quality may impact child outcomes for special education generally, and, further, that interventions to improve IEP quality may improve outcomes. However, future research is clearly needed to confirm these findings and the associated speculations.

The last set of predictors focused on implementation practice quality as measured by satisfaction and consultant fidelity. None of the three implementation practice quality variables directly predicted child goal attainment change. One possible explanation for the lack of findings is that implementation quality did not vary across teachers sufficiently to demonstrate an impact. The COMPASS consultants were two expert implementers who also happened to be the developers of the model and were thus very familiar with it. Moreover, both had extensive experience in consulting with the model and, in fact, were authors of the book-length treatment manual (Ruble et al. 2012a). Consistent with this speculation, the range of scores for the variables measuring implementation quality tended toward ceiling effects, exhibiting a restricted range. Thus, we believe the most plausible interpretation of the lack of findings is restricted variability rather than that implementation quality is unimportant.

Finally, it is worth reiterating that a comparison of the relative importance of each of the variables found significant in the separate regression analyses identified two non-traditional predictor variables, IEP quality and child engagement. Together these two factors—IEP quality, which is a function of teacher behavior, and child engagement, which is a function of the child's interaction with the instructional environment, accounted for a half of the variance in child outcomes. Notably, IEP quality accounted for about 50 % more of the variance compared to child engagement.

In addition to our primary focus on predicting variability in educational outcomes, we also examined intercorrelations between the predictor variables, some of which deserve comment. In particular, teacher stress was associated with all three measures of burnout –positively with exhaustion and depersonalization, and negatively with accomplishment and with administrator support. Together with the results discussed above showing that burnout is negatively associated to educational outcome, these results imply that both stress, perhaps via an impact on burnout, and burnout directly, may be important “early warning” variables in intervening with teachers of those with ASD. Another interesting finding was the negative association between child measures of severity (e.g., IQ, language, and adaptive behavior) and teacher satisfaction with the initial consultation and follow up coaching sessions. Teachers whose students were rated as more severe tended to be more satisfied with COMPASS. In other words, the greater the need for help, as indexed by child severity ratings, the higher the ratings of helpfulness of the intervention. This implies that COMPASS may be particularly helpful to teachers of students who present more challenging behaviors/symptoms. However, future research will be needed to verify this result.

Limitations and Future Research

The study suffered from several limitations. Because the sample size was relatively small the study may have been underpowered, resulting in higher than desirable Type II error rates. Similarly, we examined many possible associations and some may have been significant by chance, increasing Type I error rates. Also, the study was limited to young children with autism in a special education setting, and may not generalize to other age groups or settings. Finally, some of the measures were author-generated and have not been fully validated (e.g., engagement measure), thus further research is needed both to validate the measures and to replicate the results.

In summary, the search for predictors of treatment success is critical to providing effective services in the field that can sensitively attend to differences in the child, the teacher, or the intervention. The findings point toward the potential usefulness of an ecological approach that examines multiple influences on child outcomes, including teacher, child, and process variables of intervention and implementation practices. Practically, the most relevant findings point to the potential importance of modifiable factors that impact outcomes. Taken together, the findings from this study provide new directions in the ongoing search for ways to impact outcomes so that all children are responsive to their educational programs and all parents can have confidence that their child receives the best help possible.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Number R34MH073071 and RC1MH089760 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to Nancy Dalrymple, co-developer of the COMPASS framework and to the teachers, families, and children who generously donated their time and effort. We wish to thank special education directors and principals for allowing their teachers to participate. We also appreciate Dr. Michael Toland's input on earlier work and research assistants Rachel Aiello, Jessie Birdwhistell, and Ryan Johnson for assistance with data collection and coding activities.

Appendix

Autism Engagement Scale: Hints for Coding (Ruble, et al., rev. 2005)

Cooperation: Measures child's ability to cooperate with and participate in designated activity/play

-

1

The child pulls away from teacher/parent and/or falls to the ground and refuses participation in an activity. The child may cry and/or tantrum. The child may also appear apathetic or unresponsive to attempts to engage him/her in an activity.

-

1.5

The child's behavior is consistent with the description above, but the child shows limited cooperation and participation. Tantrums may be less severe; however, the child may whine or show dislike before or during cooperating with or participating in an activity.

-

2

The child's overall behavior consists of both resistance to and cooperation with activities. The child may show dislike for the activity, but may still participate. Child does not actively refuse activity.

-

2.5

The child frequently participates in and cooperates with activities. The child may show dislike for an activity and initially resist, but the child does eventually participate in that activity. Minimal refusal to participate is shown.

-

3

During the entire session, the child consistently cooperates with and participates in all activities without resistance.

Functionality: Measures child's ability to use objects in their intended manner

-

1

The child does not use objects in the manner in which they were designed to be used. Use of objects is completely non-functional (e.g., child taps pencil on forehead, mouths toy, etc.).

-

1.5

Child's appropriate use of objects is limited. The child may occasionally demonstrate correct use, such as briefly rolling a ball after mouthing it.

-

2

Child demonstrates both appropriate and inappropriate use of objects during the session. The child increasingly uses objects correctly.

-

2.5

Child frequently uses objects the way they were intended with occasional misuse of objects being demonstrated. On the whole, object use is appropriate and functional.

-

3

Objects are consistently used in the manner in which they were intended. Inappropriate use of objects is absent.

Productivity: Measures child's ability to engage in meaningful work or play behavior

-

1

Play/task does not have a purpose and is not useful. Child does not work toward completing the designated task.

-

1.5

Child makes some limited effort toward task completion. Some behaviors are useful and aid the child in completing the task/playing, although the majority of behaviors are not relevant to the task.

-

2

Child makes some progress toward task completion. Play/task behaviors are somewhat useful and or purposeful.

-

2.5

Child's behavior is mostly goal-oriented and purposeful. Significant progress is made toward task completion

-

3

All behavior is productive and oriented toward task completion. Task completion/play may lead to development of higher-level skills.

Independence: Measures child's ability to follow instructions and work on tasks without prompts

-

1

The child requires constant physical assistance to complete tasks, such as hand-over-hand assistance. Child may also require physical guidance during periods of transition to new activities.

-

1.5

Many physical prompts are needed to complete task. Although verbal/gestural prompts may be given, the child rarely responds to these prompts and they do not assist with task completion.

-

2

Physical prompts are not needed for task completion. Verbal/Gestural prompts are successful in helping the child focus work independently.

-

2.5

Very few verbal/gestural prompts are required to assist child in working independently.

-

3

Child can complete tasks without assistance and/or reminders after initial instruction.

Consistency: Measures how closely teacher's goal directed behavior for the child are aligned with the child' goal directed behavior

-

1

Teacher's goals for the child are inconsistent w/ the child's goal directed behavior. As an example, the child may be completing a puzzle about the alphabet while the teacher is instructing in science; the child may be putting toys in his mouth while the teacher is trying to get he child to play with toys functionally. The child's own goals are inconsistent with the teacher's goals for the child.

-

1.5

Teacher's goals for the child are largely inconsistent with the child's goals.

-

2

Teacher's goals for child are somewhat consistent with the child's goal directed behavior. Child may be working on alphabet puzzle while the teacher is instructing the class in reading.

-

2.5

Child and teacher goals are mostly the same.

-

3

Child and teacher have the same goal directed behaviors, working with consistency on the same lesson. Child's work may be adapted, but the content is the same. As an example, the child may complete a puzzle about the letter “L” while the teacher instructs the class to color a sheet on the letter “L”

Attention: Measures the child's interest in and attention to an activity

-

1

Child appears extremely disinterested in an activity. Child may refuse to look at task and engage in activity. Child may turn away from or ignore activity.

-

1.5

Child occasionally shows some interest in activity. Child may briefly glance at activity before redirecting attention.

-

2

Child both ignores and attends to activity. Task holds child's attention briefly.

-

2.5

Child is very attentive to task. Few periods of distraction/inattention are observed.

-

3

Child demonstrates sustained attention on task and is interested in task.

References

- Baker-Ericzen MJ, Stahmer AC, Burns A. Child demographics associated with outcomes in a community-based pivotal response training program. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9(1):52. doi:10.1177/10983007070090010601. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Itzchak E, Zachor DA. Change in autism classification with early intervention: Predictors and outcomes. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(4):967–976. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.05.001. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Itzchak E, Zachor DA. The effects of intellectual functioning and autism severity on outcome of early behavioral intervention for children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;28(3):287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrow-Woolfolk . OWLS: Oral and Written Language Scales. American Guidance Service, Inc.; Circle Pines, MN: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cytrynbaum S, Ginath Y, Birdwell J, Brandt L. Goal attainment scaling: A critical review. Evaluation Quarterly. 1979;3(1):5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst C, Trivette C. Moderators of the effectiveness of adult learning method practices. Journal of Social Sciences. 2012;8:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Eikeseth S, Eikeseth S. Outcome of comprehensive psycho-educational interventions for young children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30(1):158. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CD. Differential ability scales. Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, The Psychological Corporation; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Goin-Kochel R, Myers B, Hendricks D, Carr S, Wiley S. Ealry responsiveness to intensive behavioral intervention predicts outcomes among preschool children with autism. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2007;54(2):151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Granpeesheh D, Granpeesheh D, Dixon DR, Tarbox J, Kaplan AM, Wilke AE. The effects of age and treatment intensity on behavioral intervention outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(4):1014. [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Abidin RR, Kmetz C. The index of teaching stress: A measure of student-teacher compatibility. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35(3):239–259. [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Beszterczey SK, Katzenstein T, Park K, Goring J. Are students with ADHD more stressful to teach? Patterns of teacher stress in an elementary school sample. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10(2):79–89. doi:10.1177/10634266020100020201. [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Morrier MJ, Heflin L, Ivey ML. Autism treatment survey: Services received by children with autism spectrum disorders in public school classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(5):961–971. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 2004 Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2C.

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr., Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): Manual. consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McEachin JJ, Smith T, Lovaas OI. Long-term outcome for children with autism who received early intensive behavioral treatment. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1993;97(4):359–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrier MJ, Hess KL, Heflin LJ. Teacher training for implementation of teaching strategies for students with autism spectrum disorders [Reports-Research] Teacher Education and Special Education. 2011;34(2):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Educating children with autism. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oren T, Ogletree BT. Program evaluation in classrooms for students with autism: Student outcomes and program processes. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2000;15(3):170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky D, Helge Ronnestad M, Willutzki U. Fifty years of psychotherapy process-outcome research: Continuity and change. In: Lambert M, editor. Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 5th ed. Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 307–390. [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Perry A, Cummings A, Geier JD, Freeman NL, Hughes S, et al. Predictors of outcome for children receiving intensive behavioral intervention in a large, community-based program. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(1):592. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children—second edition (BASC-2) American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rickards AL, Rickards AL, Walstab JE, Wright-Rossi RA, Simpson J, Reddihough DS. A randomized, controlled trial of a home-based intervention program for children with autism and developmental delay. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(4):308. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318032792e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Vismara LA. Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):8–38. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, Robson D. Individual and environmental influences on engagement. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1457–1468. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0222-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, Dalrymple NJ, McGrew JH. The effects of consultation on Individualized Education Program outcomes for young children with autism: The collaborative model for promoting competence and success. Journal of Early Intervention. 2010a;32(4):286–301. doi: 10.1177/1053815110382973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, Dalrymple N, McGrew J. The collaborative model for promoting competence and success for students with ASD. Springer; New York: 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, McDuffie A, King A, Lorenz D. Caregiver responsiveness and social interaction behaviors of young children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2008;28(3):158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble LA, McGrew J, Dalrymple N, Jung LA. Examining the quality of IEPS for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010b;40(12):1459–1470. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1003-1. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, McGrew J, Toland M. Goal attainment scaling as an outcome measure in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012b;42(9):1974–1983. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1446-7. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble L, McGrew J, Toland M, Jung L. A randomized controlled trial of web-based and face-to-face teacher coaching in autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(3):566–572. doi: 10.1037/a0032003. doi:10.1037/a0032003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallows GO, Graupner TD. Intensive behavioral treatment for children with autism: Four-year outcome and predictors. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2005;110(6):417–438. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[417:IBTFCW]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, DeVellis RF, Daly K. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1980;10(1):91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Schreibman L, Stahmer AC, Barlett VC, Dufek S. Brief report: Toward refinement of a predictive behavioral profile for treatment outcome in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(1):163. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer MR, Schreibman L. Individual behavioral profiles and predictors of treatment effectiveness for children with autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):525–538. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Buch GA, Gamby TE. Parent-directed, intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21(4):297–309. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Groen AD, Wynn JW. Randomized trial of intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2004;105(4):269–285. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2000)105<0269:RTOIEI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV. The Vineland adaptive behavior scales. In: Newmark CS, editor. Major psychological assessment instruments. Vol. 2. Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 1995. pp. 199–231. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer AC, Collings NM, Palinkas LA. Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(2):66–79. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200020301. doi:10.1177/10883576050200020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer AC, Schreibman L, Cunningham AB. Toward a technology of treatment individualization for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.043. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoelb M, Stoelb M, Yarnal R, Miles J, Takahashi TN, Farmer JE, et al. Predicting responsiveness to treatment of children with autism: A retrospective study of the importance of physical dysmorphology. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2004;19(2):66. [Google Scholar]

- Sutera S, Pandey J, Esser EL, Rosenthal MA, Wilson LB, Barton M, et al. Predictors of optimal outcome in toddlers diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Szatmari P, Bryson SE, Boyle MH, Streiner DL, Duku E. Predictors of outcome among high functioning children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(4):520. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivette CM, Dunst CJ, Hamby DW, O'Herin CE. Characteristics and consequences of adult learning methods and strategies. Vol. 2. Winterberry Press; Asheville, NC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Turner LM, Stone WL. Variability in outcome for children with an ASD diagnosis at age 2. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(8):793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeargin-Allsopp M, Rice C, Karapurkar T, Doernberg N, Boyle C, Murphy C. Prevalence of autism in a US metropolitan area. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(1):49–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.49. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder P, Yoder P, Stone WL. Randomized comparison of two communication interventions for preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):426. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel RH, Zabel MK. Burnout among special education teachers and perceptions of support [Reports-Research] Journal of Special Education, Leadership. 2002;15(2):67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zachor DA, Ben-Itzchak E, Rabinovich A-L, Lahat E. Change in autism core symptoms with intervention. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2007;1(4):304–317. [Google Scholar]