Inflammation and dyslipidaemia play crucial, synergistic roles in the deterioration that occurs during the progression of atherosclerosis [1,2]. However, the exact mechanisms of atherosclerosis have not been completely elucidated. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase that plays important roles in regulating cellular homeostasis and metabolism. The mTOR protein nucleates at least two distinct multi-protein complexes, namely mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) [3]. The mTORC1 integrates stimulating signals and then phosphorylates p70 S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1). This activity results in cell growth, activation of translation, and ribosome biosynthesis [4–6]. Rapamycin and its analogues only inhibit the activity of mTORC1 [3]. mTORC2 primarily modulates cell survival, cell polarity, cytoskeletal organisation, and activity of the aldosterone-sensitive sodium channel [7]. Our previous studies demonstrated that inflammation disrupts the feedback regulation of the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLr) and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) to increase intracellular cholesterol uptake and biosynthesis, which results in intracellular lipid accumulation and foam cell formation. However, these effects were blocked by rapamycin treatment through the inhibition of SREBP-2 expression and a decrease in SCAP/SREBP-2 complex translocation from the ER to the Golgi [1,8]. These findings suggest that the mTOR pathway may be involved in the disruption of cholesterol homeostasis that occurs in response to inflammatory stress. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to investigate the role of the mTOR pathway in the progression of atherosclerosis in both apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE KO) mice and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) under inflammatory stress.

To induce inflammation, we used subcutaneous injection of 10% casein in male ApoE KO mice and lipopolysaccharide stimulation in rat VSMCs. ApoE KO mice with a C57BL/6 genetic background were studied under protocols approved by the Ethical Committee of Southeast University and followed the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Eight-week-old ApoE KO mice were randomly assigned to daily subcutaneous injections of 0.5 ml PBS (control), 8 mg/kg/q.o.d rapamycin (Rapa), 10% casein (casein), or rapamycin plus casein (casein plus Rapa). The mice were fed the Western diet containing 21% fat and 0.15% cholesterol for 8 weeks.

Results showed that inflammation increased lipid accumulation in aortas of ApoE KO mice and in VSMCs (Fig. 1A and B), which were correlated with increased expressions of LDLr, sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), and SREBP-2 as well as with enhanced translocation of SCAP/SREBP-2 complex from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to Golgi. Furthermore, inflammation increased both the percentage of cells in the S phase of cell cycle and protein expressions of the phosphorylated forms of retinoblastoma tumour suppressor protein (Rb), mTOR, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1), and P70 S6 kinase. After treatment with rapamycin or mTOR siRNA, the activity of mTOR pathway was blocked. Interestingly, the expression levels of LDLr, SCAP, and SREBP-2 and the translocation of SCAP/SREBP-2 complex from the ER to the Golgi in treated VSMCs were decreased even in the presence of inflammatory stress (Fig. 2A–D).

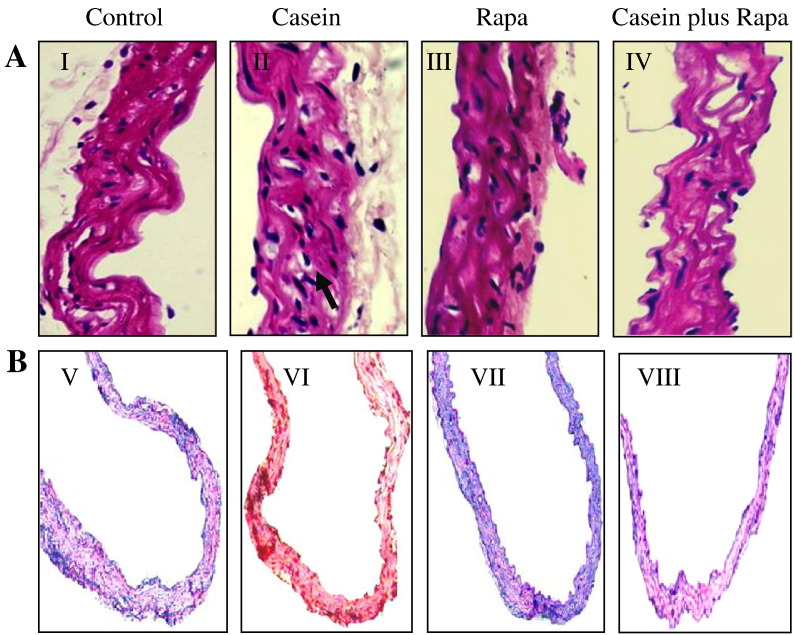

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the mTOR pathway decreased the lipid accumulation induced by inflammation in vivo and in vitro. ApoE KO mice were fed the Western diet for eight weeks and received either no treatment (Control, I and V) or were treated by injection with 10% casein (Casein, II and VI), 8 mg/kg/q.o.d rapamycin (Rapa, III and VII) or rapamycin plus casein (Rapa plus Casein, IV and VIII). (A) The lipid accumulation in the aorta in ApoE KO mice was examined by staining with H&E (I–IV, 400 × magnification) and (B) Oil Red O (V–VIII, 400 × magnification). An area populated with foam cells is indicated by an arrow in II.

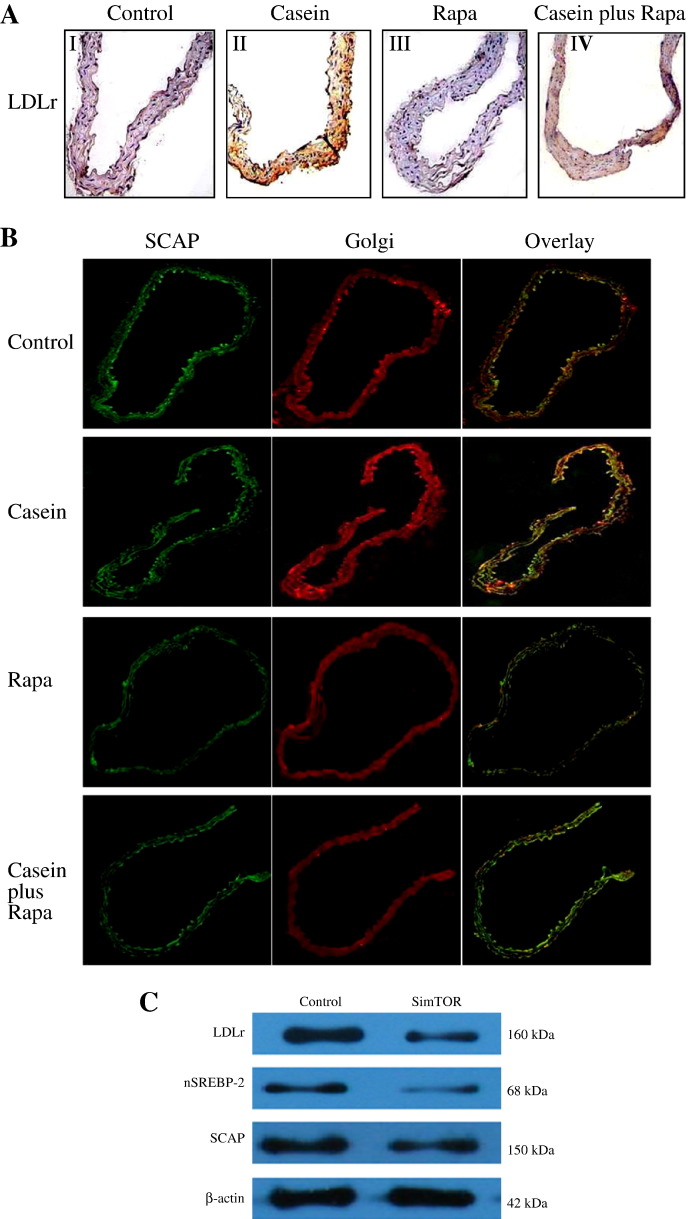

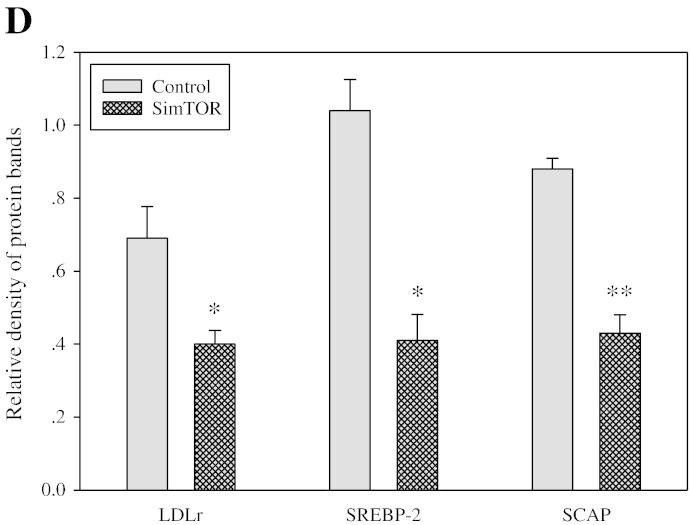

Fig. 2.

mTOR inhibition downregulated the expression of the LDLr pathway induced by inflammation in vivo and in vitro. ApoE KO mice were fed the Western diet for eight weeks and received either no treatment (Control, I) or were treated by injection with 10% casein (Casein, II), 8 mg/kg/q.o.d rapamycin (Rapa, III) or rapamycin plus casein (Rapa plus Casein, IV). (A) The protein expression level of LDLr in ApoE KO mice was examined by immunostaining of cross-sections of the aorta. Brown staining indicates areas of LDLr expression (200 × magnification). (B) The translocation of SCAP escorting SREBP-2 from the ER to the Golgi was checked by immunofluorescent staining using cross-sections of the aorta. The immunofluorescent signals were detected by confocal microscopy. (C & D) VSMCs were incubated for 24 h either in serum-free medium (Control) or serum-free medium containing 25 μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) alone, 10 ng/ml of rapamycin alone (Rapa) or 25 μg/ml of LPS plus 10 ng/ml of rapamycin (LPS plus Rapa). The protein expression of LDLr, nuclear SREBP-2 (nSREBP-2), and SCAP were determined by Western blotting. The histogram shows the means ± SD of the densitometric scans of the LDLr, SREBP-2 and SCAP protein bands from three experiments following normalisation by comparison with β-actin. *p < 0.05 vs. Control; **p < 0.001 vs. Control.

Our findings demonstrate for the first time that inflammation disrupts LDLr feedback regulation through the activation of mTOR pathway. Increased mTORC1 activity was found to upregulate SREBP-2-mediated cholesterol uptake through Rb phosphorylation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Yaxi Chen from Chong Qing University for providing us big support in the experiments. This work was supported by grants 81170792, 81070571, and 81130010 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Ma K.L., Ruan X.Z., Powis S.H., Moorhead J.F., Varghese Z. Anti-atherosclerotic effects of sirolimus on human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6):H2721–H2728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01174.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruan X.Z., Moorhead J.F., Tao J.L. Mechanisms of Dysregulation of Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Expression in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Inflammatory Cytokines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(5):1150–1155. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000217957.93135.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M.N. TOR signalling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124(3):471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay N., Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18(16):1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D.H., Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110(2):163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M., Kim D.H. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieberthal W., Levine J.S. Mammalian target of rapamycin and the kidney. I. The signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303(1):F1–F10. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00014.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma K.L., Varghese Z., Ku Y. Sirolimus inhibits endogenous cholesterol synthesis induced by inflammatory stress in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(6):H1646–H1651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00492.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]