Abstract

Backgrounds and Aims

Current research in plant science has concentrated on revealing ontogenetic processes of key attributes in plant evolution. One recently discussed model is the ‘transient model’ successful in explaining some types of inflorescence architectures based on two main principles: the decline of the so called ‘vegetativeness’ (veg) factor and the transient nature of apical meristems in developing inflorescences. This study examines whether both principles find a concrete ontogenetic correlate in inflorescence development.

Methods

To test the ontogenetic base of veg decline and the transient character of apical meristems the ontogeny of meristematic size in developing inflorescences was investigated under scanning electron microscopy. Early and late inflorescence meristems were measured and compared during inflorescence development in 13 eudicot species from 11 families.

Key Results

The initial size of the inflorescence meristem in closed inflorescences correlates with the number of nodes in the mature inflorescence. Conjunct compound inflorescences (panicles) show a constant decrease of meristematic size from early to late inflorescence meristems, while disjunct compound inflorescences present an enlargement by merging from early inflorescence meristems to late inflorescence meristems, implying a qualitative change of the apical meristems during ontogeny.

Conclusions

Partial confirmation was found for the transient model for inflorescence architecture in the ontogeny: the initial size of the apical meristem in closed inflorescences is consistent with the postulated veg decline mechanism regulating the size of the inflorescence. However, the observed biphasic kinetics of the development of the apical meristem in compound racemes offers the primary explanation for their disjunct morphology, contrary to the putative exclusive transient mechanism in lateral axes as expected by the model.

Keywords: Transient model, inflorescence, ontogeny, conjunct, disjunct, vegetativeness, terminal flower, raceme, botryoid, panicle, compound raceme, apical meristem

INTRODUCTION

Plant modelling helps understanding how the plant body is constructed (Heisler and Jonsson, 2007; Cieslak et al., 2011; Prusinkiewicz and Runions, 2012). Ontogenetic research may then play a role revealing (or not) the concrete basis of the postulated conjectures. One of the currently discussed models is the unifying inflorescence model proposed by Prusinkiewicz et al. (2007), also known as the ‘transient model’. The model aims to explain types of inflorescence architecture in relation to ontogenetic decisions at the inflorescence meristem based on simplified information of plant genetic control. Does the postulate of this model find a concrete base in ontogeny or does it only represent formal expectations?

The transient model is based on the existence of a factor in the apical meristem (AM) called ‘vegetativeness’ (veg) which declines in each plastochron of the inflorescence development, i.e. time interval between the production of two subsequent lateral meristems, until it reaches a certain threshold at a given time (TA). At this time, the AM transforms into a flower meristem giving rise to a terminal flower. The previously produced lateral meristems also possess a certain veg value and behave in the same way as the main axis, producing further lateral meristems until veg sufficiently declines at time TB, converting the lateral AMs into flowers as well. An even decline of veg in all branches allows all meristems to transform into flowers at the same time (TB = TA; see Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). The last formed lateral meristems (distal in the inflorescence) will have the lowest value of veg and thus convert into flowers immediately, while the first-produced lateral meristems (proximal in the inflorescence) will have enough veg to produce as many nodes as the main axis until floral conversion. The resulting branching system is called a ‘panicle’ and corresponds to a compound inflorescence with pyramidal form, showing a continuous decrease in the branching degree from proximal to distal resulting in a conjunct shape with flowers topping each shoot (Fig. 1A).

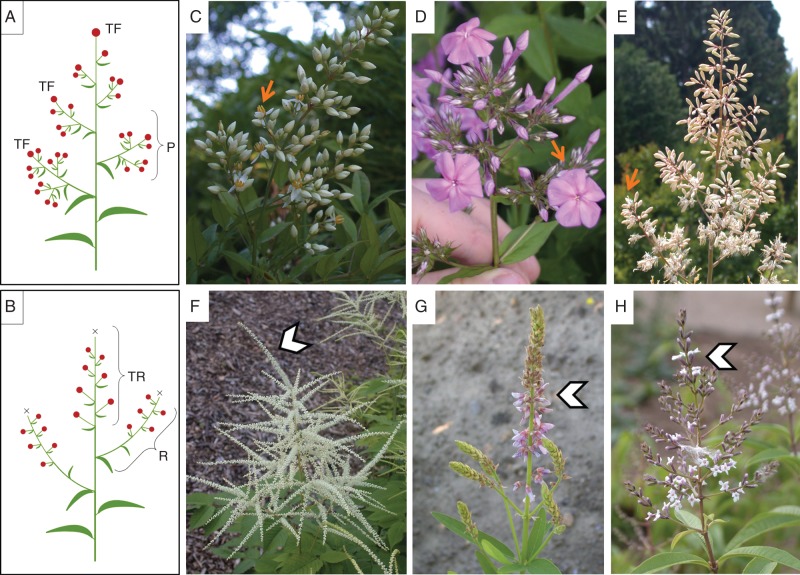

Fig. 1.

Inflorescence types (A, B) and studied species (C–E). (A) Scheme of a panicle characterized by its pyramidal form, showing gradual reduction of lateral partial inflorescences to individual flowers. Terminal flowers terminate every axis (TF). (B) Scheme of a compound raceme. Compound racemes are characterized by their multiple racemes in lateral (R) and terminal (TR) positions and lack of terminal flowers (X). (C–E) Panicles (with arrows indicating early opening terminal flowers) and (F–H) compound racemes (with arrowheads pointing at the terminal racemes): (C) Nandina domestica (Berberidaceae); (D) Phlox drummondii (Polemonaceae); (E) Macleaya odorata (Papaveraceae); (F) Aruncus dioicus (Rosaceae); (G) Desmodium canadense (Fabaceae); (H) Aloysia triphylla (Verbenaceae). Note that the racemes of D. canadense (G) bear two-flowered fascicles instead of single flowers. Abbreviations: TR, terminal raceme; R, lateral raceme; TF, terminal flower; P, partial inflorescence.

When the decline of veg is not homogenous, then TB ≠ TA. When TB < TA, lateral meristems transform into flowers earlier than the main axis does. An extreme of this scenario supposes a minimal presence of veg in newly formed lateral meristems, implying an immediate transformation into flowers. This sequence results in a simple inflorescence called botryoid: a single main axis bearing lateral flowers and topped by a terminal flower (Troll, 1964; Prenner et al., 2009; Endress, 2010). The size of this botryoid would be determined by TA, i.e. the number of plastochrones veg requires for decreasing before the main axis converts into a terminal flower. Considering the interplay of veg in main and lateral meristems, this model is able to explain the genesis of compound and simple inflorescences topped by terminal flowers, otherwise called ‘closed’ inflorescences (Troll, 1964; Weberling, 1981).

Nevertheless, inflorescences lacking terminal flowers also occur, usually referred to as ‘open’ inflorescences (Troll, 1964; Weberling, 1981), which include simple and compound racemes. Racemes are easily explained by the transient model departing from a botryoid whose TA tends to be infinite. An infinite TA implies veg in the AM never declining to the extent by which it is transformed into a terminal flower thus leaving the main axis ‘open’. On the other hand, compound racemes consist of a main axis bearing lateral racemes at the base and one terminal raceme at the top (Fig. 1B). This form of compound inflorescence contrasts with the panicle, showing no gradual diminution of branching from proximal to distal, but rather an abrupt change from lateral racemes to lateral flowers, resulting in a ‘disjunct’ shape. According to the transient model the lateral racemes are the consequence of the ‘transient state’ of the lateral meristems: when the first lateral meristems are produced, the veg value is supposed to be not low enough to convert into flowers, and then the state of the lateral meristem would revert from ‘B’ to ‘A’. This reversion would create ‘new’ main shoots that originate racemes in lateral position (Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007).

Taken together, the transient model works along two main ideas: (1) the decline of veg in the AM capable of determining the number of nodes of an inflorescence; and (2) the transient state of lateral meristems causing the disjunct shape of compound inflorescences.

If the model is appropriate we should expect an expression of these key processes in the ontogeny of inflorescences. We predict that size variation of the meristematic tissue should be a morphometric correlate of both the degree of veg in the AM and of the ontogenetic determination of the disjunct shape in compound racemes.

In the present study we are testing the ontogenetic base of ‘vegetativeness’ and ‘transientness’ of inflorescence meristems through a detailed study of AM size in relevant inflorescence types of different angiosperm families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vegetativeness at the AM

Considering that veg determines the size of closed inflorescences according to its declining rate in the AM, and that the dimension of the AM declines in the course of inflorescence ontogeny (Bull-Hereñu and Claßen-Bockhoff, 2011), initial veg of the AM could be referred to AM size. Thus, we investigated the initial size of the AM and compared it with the dimension of the mature inflorescence. For this purpose, we reanalysed raw data presented elsewhere (Bull-Hereñu and Claßen-Bockhoff, 2011). The data pool included seven species with closed inflorescences from four families (N = 25 buds measured), including Berberis aristata D.C., Mahoberberis × aquisargentii Jensen (Berberidaceae); Capnoides sempervirens (L.) Borkh., Dicentra eximia (Ker-Gawl.) Torr. (Papaveraceae); Agrimonia eupatoria L. var. Alba, Neviusia alabamensis A. Gray (Rosaceae) and Campanula thyrsoides L. (Campanulaceae). Inflorescence size was measured in terms of the number of nodes present in the main inflorescence axis ranging from 5·1 (s.d. = 0·6) to 105 nodes (s.d. = 26·7; Bull-Hereñu and Claßen-Bockhoff, 2011). Plant material was collected at the Botanical Garden of the Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz (Germany) and stored in 70 % EtOH. It followed dehydration in alcohol–acetone series and critical point-drying (BAL-TEC CPD030). The material was mounted and sputter-coated with gold (BAL-TEC SCD005) and observed under a scanning electron microscope (ESEM XL-30 Philips). The size of the inflorescence meristem was expressed relative to its lateral primordium in terms of its insertion angle or ‘leaf arc’ (Rutishauser, 1998). For leaf arc parameters we only considered individuals in early ontogeny (one-third of nodes produced). We regressed the leaf arc parameter of meristems against the mean mature inflorescence size in the respective species.

Transient meristems in compound inflorescences

To distinguish between transient and non-transient meristems in compound inflorescences, we investigated the development of conjunct panicles and disjunct compound racemes. According to the ontogeny-based inflorescence concept (Claßen-Bockhoff and Bull-Hereñu, 2013), we only considered as compound racemes inflorescences composed of several lateral and one single terminal raceme (originally referred as ‘heterothetic compound racemes’; Troll, 1964; Weberling, 1981). We defined two developmental stages in the ontogeny of the compound inflorescences: early and late. Early inflorescence meristem (EIM) was defined as the main inflorescence meristem just after reproductive induction when it produces lateral shoots (or partial inflorescences). Late inflorescence meristem (LIM) was defined as the main inflorescence meristem at the time when it produces just single flowers. In a compound raceme, LIM corresponds to the AM of the terminal raceme, and in a panicle it corresponds to the AM producing few lateral flowers and the terminal flower (Fig. 1 and top sketches of Figs 4 and 5). Hence, the transition from EIM to LIM is the key ontogenetic moment when the disjunct shape of a compound raceme is originated (top sketches in Fig. 5). We therefore compared EIM and LIM in panicles and compound racemes to explore the ontogenetic base of the generation of the disjunct and the conjunct shape in compound inflorescences.

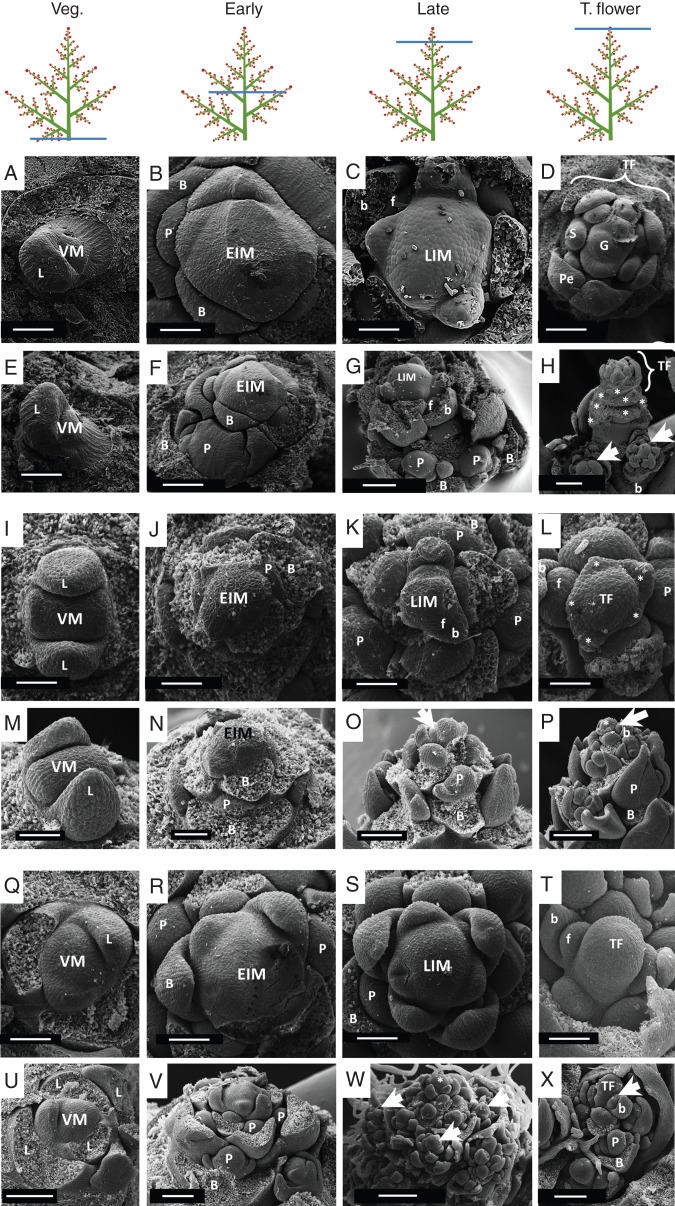

Fig. 4.

SEM images depicting the ontogeny of panicles. Images are organized in columns according to the ontogenetic state: first column, vegetative meristems (VM); second column, early inflorescence meristems (EIM) forming lateral partial inflorescences (P); third column, more advanced developing inflorescences topped by their late meristems (LIM) that produce lateral flowers (f); fourth column, formation of the terminal flower (TF). (A–H) Nandina domestica: (A–D) top views, (E–H) side views of apical meristems; (A, E) vegetative meristem (VM) producing a large leaf primordium (L); (B, F) early inflorescence meristem (EIM) originating few lateral partial inflorescence primordia (P) subtended by bracts (B); (C, G) late inflorescence meristem (LIM) with distal flower primordia (f), proximal partial inflorescence primordia (P) and their respective subtending bracts (labelled B and b) – note that the LIM is smaller than the EIM in (B) and (F); (D, H) young terminal flower (TF) that has developed from the late inflorescence meristem. Stamen (S), petal (Pe) and gynoecium (G) primordia are visible as some lateral young flowers (arrowheads). Asterisks indicate scars of sepals of the TF. (I–P) Phlox drummondii: (I, M) vegetative meristem (VM) with opposite leaf primordia (L) in decussate phyllotaxis; (J, N) EIM showing transition to spiral phyllotaxis, lateral partial inflorescence primordia (P) and subtending bracts (B); (K, O) LIM showing incipient bract (b) and flower primordium (f), partial inflorescence primordia (P) and their respective subtending bracts (B) – note that the LIM in (K) is smaller than the EIM in (J); (L) developing terminal flower (TF) at the top of the main axis with young calyx (asterisk), lateral flower (f), partial inflorescence (P) and their respective subtending bract (b and B) primordia; (P) same sample as in (L) with partial inflorescences at the base (P), developing lateral flower primordium near the top (arrowhead) and a young terminal flower (asterisk). (Q–X) Macleaya odorata: (Q, U) Vegetative meristem (VM) showing large leaf primordia (L); (R, V) early inflorescence meristem (EIM) showing lateral partial inflorescence primordia (P) and their subtending bracts (B); (S, W) late inflorescence meristem (LIM) – note that the late inflorescence meristem is smaller than the early inflorescence meristem (EIM) in (R); (T) young terminal flower (TF) terminating the axis – note its developmental advance in comparison with the lateral flower primordia (f); (X) partial inflorescence showing the terminal flower (TF) at the top of the axis, lateral flower primordia (arrowhead) subtended by bracts (b) near the TF and partial inflorescence primordia (P) subtended by bract (B) near the base. Abbreviations: VM, vegetative meristem; EIM, early inflorescence meristem; LIM, late inflorescence meristem; P, partial inflorescence; B, subtending bract of a partial inflorescence; b, flower subtending bract; S, stamen primordium; Pe, petal; G, gynoecium. Other abbreviations as in Fig. 2. Scale bars: (A–E, I–N, Q–T) = 100 µm; (F, G, O, U, V, X) = 200 µm; (H, P, W) = 400 µm.

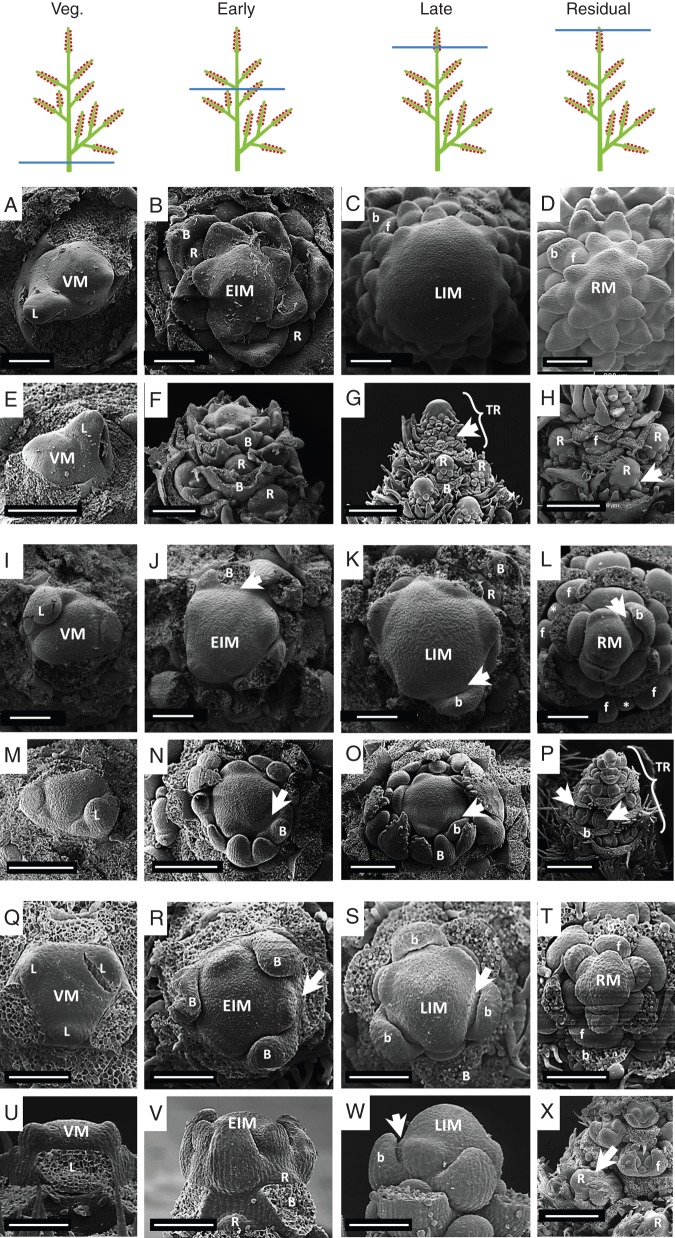

Fig. 5.

SEM images depicting ontogeny of compound racemes. Images are arranged as in Fig. 4. (A–H) Aruncus dioicus: (A, E) vegetative meristem (VM) showing one leaf primordium (L); (B, F) early inflorescence meristem (EIM) showing at its periphery bract (B) and lateral raceme (R) primordia – note the larger size of the leaf primordium (L) in (A) and (E) and the acropetal development of the lateral raceme primordia (R), i.e. from bottom to top; (C, G) late inflorescence meristem (LIM) that produces flower primordia (f and arrowhead) subtended by bracts (b) – note that the late inflorescence meristem (LIM) is larger than the early inflorescence meristem (EIM in B), and also that the terminal raceme (TR) is larger than the many developing lateral racemes (R); (D) residual meristem (RM) of an inflorescence – note that floral primordia (f) and subtending bracts (b) are more advanced than in (C); (H) detail of the compound raceme showing the disjunct transition zone between lateral racemes (R) and lateral flowers (f) – note the dramatic developmental difference between the proximal young flowers of the terminal raceme (f) and the flower primordia at the base of the lateral raceme (arrow). (I–P) Desmodium canadense: (I, M) vegetative meristem (VM) showing leaf primordia (L); (J, N) early inflorescence meristem (EIM) showing the first formed lateral raceme primordia (arrowhead) subtended by trifoliate subtending bracts (B, partly removed); (K, O) late inflorescence meristem (LIM) already producing two flowered fascicles (arrowhead) subtended by a unifoliate bract (b) – also note an older raceme primordium (R) subtended by its respective trifoliate bract (B, partly removed) and that the late inflorescence meristem (LIM) is larger than the early inflorescence meristem (EIM in J); (L, P) residual inflorescence meristem (RM) – note that flower primordia are visible in older nodes separated by a residuum (asterisk) and also younger fascicle primordia (arrowhead) and their respective subtending bracts (b) can be seen adjacent to the rm. (Q–X) Aloysia triphylla: (Q, U) vegetative meristem (VM) obtained from a sprouting shoot with leaf primordia (L) corresponding to the sixth node – note the tricussate phyllotaxis and flat aspect of the vegetative meristem (VM); (R, V) early inflorescence meristem (EIM) with lateral raceme subtending bract (B) – note that the marked whorl corresponds to the eleventh node, the slight curvature of the early inflorescence meristem (EIM) and that the raceme primordia (R) are formed above their subtending bracts (B); (S, W) late inflorescence meristem (LIM) showing flower primordia (arrowhead) and flower-subtending bracts (b) – note that the flower primordia marked correspond to the 18th node and that late and early meristems seem to have a similar extension in width (see R) but a different curvature (see V); (T) residual meristem (RM) reduced in size and flower primordia (f); (X) detail of compound raceme showing the disjunct transition zone between lateral racemes (R) and lateral flowers (f) – note the dramatic developmental difference between the basal-most young flower (f) of the terminal raceme compared with the floral primordia at the base of the lateral raceme (arrow). Abbreviations: R, lateral raceme; TR, terminal raceme. Other abbreviations as in Figs 2 and 3. Scale bars: (A–D, I–L, Q–X) = 100 µm; (E, F, M–O) = 200 µm; (G, H, P) = 400 µm.

Panicles were studied in Nandina domestica Thunb. ex Murray (Berberidaceae), Phlox drummoldii L. (Polemonaceae) and Macleaya odorata (Willd.) R.BR. (Papaveraceae). Compound racemes were studied in Aloysia triphylla (L'her.) Britton (Verbenaceae), Aruncus dioicus (Walter) Fernald (Rosaceae) and Desmodium canadense (L.) DC. (Fabaceae). In this last species, the nodes of each raceme bear two-flowered units (termed ‘fascicles’) instead of single flowers, and therefore is elsewhere referred as a compound ‘pseudoraceme’ (Tucker, 1987). Nevertheless, as each fascicle develops from a common axillary primordium (Tucker, 1987) and the general shape of the inflorescence is disjunct, we assumed Desmodium to be comparable in ontogenetic terms to the resting compound racemes.

The plant material was collected and handled as mentioned above.

RESULTS

Relationship between size of meristem and inflorescence dimension

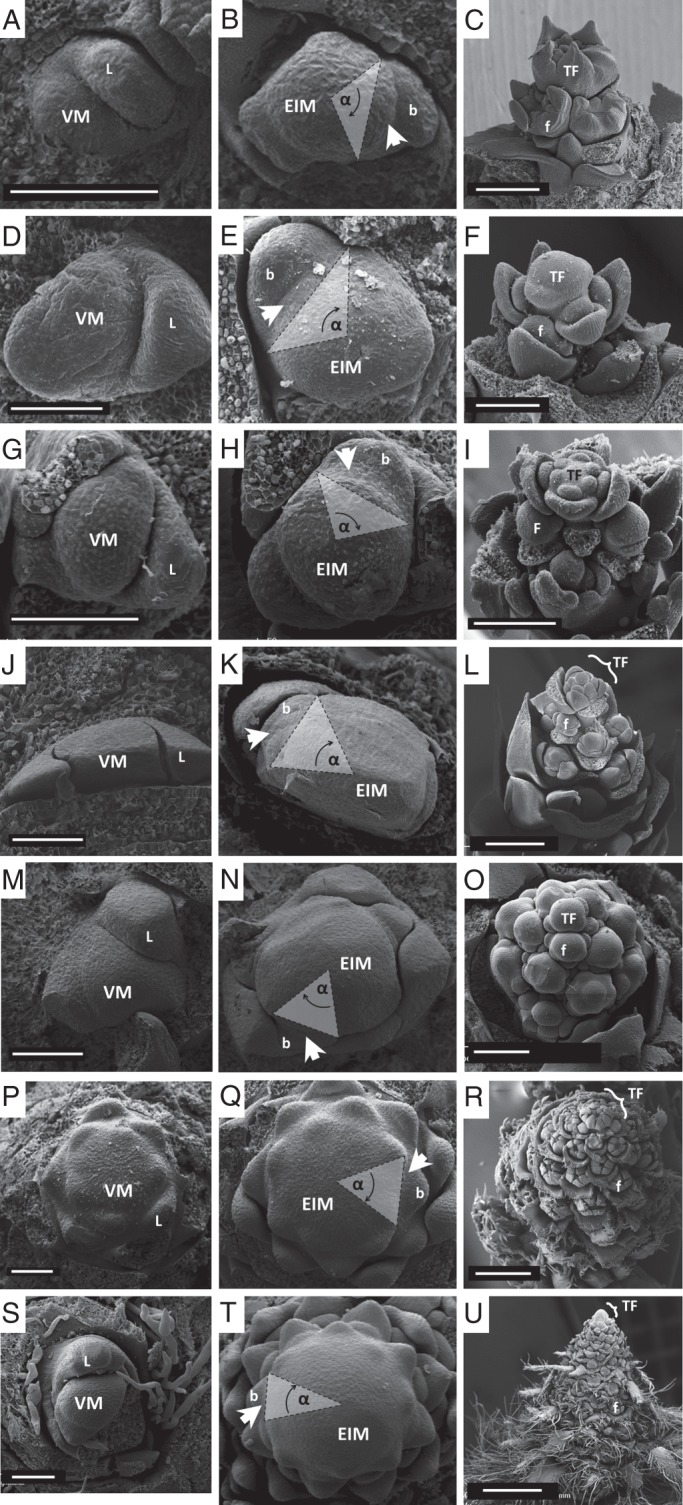

The inflorescence meristems of the closed inflorescences (Fig. 2B, E, H, K, N, Q, T) are larger than their respective vegetative meristems (Fig. 2A, D, G, J, M, P, S), revealing the increase in volume caused by the reproductive stimulus. The insertion angle of lateral primordia (‘leaf arc’, α angle in Fig. 2B, E, H, K, N, Q, T) is larger in inflorescences that produce few flowers (Fig. 2C, F, I) and smaller in inflorescences with many flowers (Fig. 2L, O, R, U).

Fig. 2.

SEM images depicting ontogeny of closed inflorescences. Each row contains images of one species and each column represents one ontogenetic state: first column, vegetative meristem (VM); second column, early inflorescence meristem (EIM; same scale as in first column); third column, the complete inflorescence formed. Species are ordered according to the number of nodes in the mature inflorescence from small (top) to large (bottom) – smaller inflorescences present relatively smaller EIMs (higher α values; where α = insertion angle of the youngest primordium) and larger inflorescences show larger EIMs (smaller α values). Arrowheads denote the youngest lateral primordium. (A–C) Neviusia alabamensis (Rosaceae: 5·1 ± 0·7 nodes); (D–F) Dicentra eximia (Papaveraceae; 5·1 ± 0·6 nodes); (G–I) Capnoides sempervirens (Papaveraceae; 5·5 ± 0·6 nodes); (J–L) Mahoberberis × aquisargentii (Berberidaceae; 12·2 ± 2·0 nodes); (M–O) Berberis aristata (Berberidaceae; 16·2 ± 1·8 nodes); (P–R) Campanula thyrsoides (Campanulaceae; 94·3 ± 25·8 nodes); (S–U) Agrimonia eupatoria (Rosaceae; 105·0 ± 25·7 nodes). Abbreviations: L, leaf primordium; b, subtending bract; f, lateral young flowers; TF, terminal flower. Scale bars: first two columns = 100 µm; (C, F, I, O) = 200 µm; (L) = 500 µm; (R, U) = 1 mm.

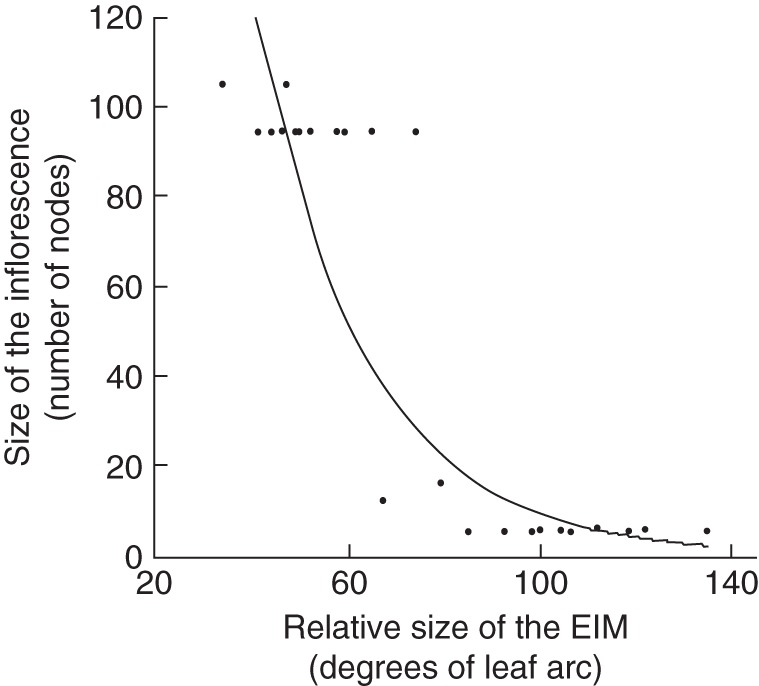

The analysis of the numeric data shows an exponential relationship between the leaf arc of the inflorescence meristem and the number of nodes in the mature inflorescence (significant logarithmic regression R2 = 0,81; Fig. 3). Larger inflorescence meristems (lower leaf arcs) produce inflorescences of many nodes, while smaller inflorescence meristems can produce only short inflorescences (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Logarithmic regression between the relative size of early inflorescence meristems (EIM) of seven species and the size of their respective mature inflorescences. The leaf arc parameter is negatively proportional to the relative size of the meristem thus larger EIMs (left on the x-axis) produce larger inflorescences. The declining curve can be referred to the degree of the putative veg factor present in the inflorescence meristem (Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). Plot clouds arranged in lines correspond to measurements in one species.

Ontogeny of conjunct panicles

Nandina domestica (Figs 1C and 4A–H)

The vegetative meristem of N. domestica (Fig. 4A, E) enlarges to produce an EIM (Fig. 4B, F) with lateral primordia (P). These lateral primordia will give rise to lateral partial inflorescences (Fig. 4F). While producing these lateral primordia, the inflorescence meristem gradually diminishes in size (compare B and C in Fig. 4) to convert into a LIM that produces flowers (Fig. 4C, G). Finally, the LIM transforms into a terminal flower (Fig. 4D, H).

Phlox drummondii (Figs 1D and 4I–P)

In the vegetative state, P. drummondii shows a decussate phyllotaxis (Fig. 4I, M) that changes to a spiral one when the meristem converts to the reproductive phase and EIM is formed (Fig. 4J). This EIM produces lateral primordia (Fig. 4N) which later will give rise to partial inflorescences. While more lateral primordia are produced, the EIM is reduced in size until it converts into an LIM producing lateral flowers instead of partial inflorescences (Fig. 4K, O). Finally the LIM converts into a terminal flower which is more advanced in development than the immediate neighbours (Fig. 4L, P).

Macleaya odorata (Figs 1E and 4Q–X)

The vegetative meristem of Macleaya (Fig. 4Q, U) enlarges when getting into the reproductive phase configuring its EIM (Fig. 4R). The EIM starts producing lateral primordia (Fig. 4V) which will form lateral partial inflorescences. The size of the EIM decreases during the formation of lateral inflorescence primordia merging into the LIM (Fig. 4S). The panicle adopts its ramified pyramidal aspect as the partial inflorescences develop (Fig. 4W). Finally, the main axis forms some lateral flowers before its meristem transforms into a terminal flower. Lateral partial inflorescences develop in the same way (Fig. 4T, X).

Ontogeny of disjunct compound racemes

Aruncus dioicus (Figs 1F and 5A–H)

The reproductive meristem (Fig. 5B) is slightly larger than the vegetative meristem (Fig. 5A, E). This EIM produces lateral racemes (Fig. 5B, F: R). Once the lateral racemes have been formed, the inflorescence apex enlarges and converts into a late inflorescence meristem (LIM) which produces lateral flower primordia (Fig. 5C: f). The LIM gives rise to the terminal raceme which is larger than the many lateral racemes (Fig. 5G) and advanced in development (Fig. 5H). Towards the end of the ontogeny the LIM is almost completely used up leaving a sterile residual meristem (RM) (Fig. 5D).

Desmodium canadense (Figs 1G and 5I–P)

Similar to Aruncus dioicus, the initial ontogeny in this papilionoid legume is characterized by a slight enlargement of the vegetative AM giving rise to the EIM (Fig. 5I: VM, J: EIM). The EIM gives rise to several lateral raceme primordia (arrowhead) which are subtended by trifoliate bracts (Fig. 2J, N: b). Shortly after this, the EIM enlarges a second time to give rise to the LIM which will produce the terminal raceme with two-flowered unit primordia subtended by unifoliate bracts (Fig. 5K, O: b). After producing many of these units the LIM decreases in size leaving a sterile tip (RM) (Fig. 5L). The terminal raceme is evident at this point (Fig. 5P: TR).

Aloysia triphylla (Figs 1H and 5Q–X)

The flat vegetative meristem (Fig. 5Q, U) slightly enlarges in its diameter (Fig. 5R) and vertical curvature (Fig. 5V) when merging into the reproductive stage. This EIM produces lateral racemes (Fig. 5V: R). After the formation of lateral racemes, the EIM increases its vertical curvature even more (Fig. 5W) enlarging its volume. The so configured LIM produces flower primordia in the species-characteristic tricussate pattern (Fig. 5S, W). When all flowers are formed a small sterile tip can be seen at the top of the terminal raceme (Fig. 5T: RM). The terminal raceme is ontogenetically more advanced in comparison with the lateral racemes (Fig. 5X).

DISCUSSION

The veg factor is consistent with meristem size in closed inflorescences

The significant relation between the size of young inflorescence meristems and the dimension of closed inflorescences allows us to relate the veg factor to the AM size at a given time. Thus the size of the AM predetermines the number of nodes it can produce before it transforms into a terminal flower. Actually, through inflorescence ontogeny, the AM decreases in size until it reaches a geometric configuration proper for the production of a terminal flower (Bull-Hereñu and Claßen-Bockhoff, 2011). This is comparable to the proposed declining dynamics of the veg factor prior to the formation of a terminal flower (Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). The model associates the veg factor with the TERMINAL FLOWER LOCUS 1 (TFL1) gene product (Shannon and Meekswagner, 1991; Alvarez et al., 1992), because studies have shown that the presence of TFL1 in the AM prevents the formation of a terminal flower (Szczesny et al., 2009). Closed inflorescences demand that the TFL1 product disappears from the AM allowing the formation of a terminal flower. If we assume a decline of TFL1 (veg factor) in closed inflorescences, then the decrease in size of the AM could be an indicator for this process.

Transient model in compound inflorescences

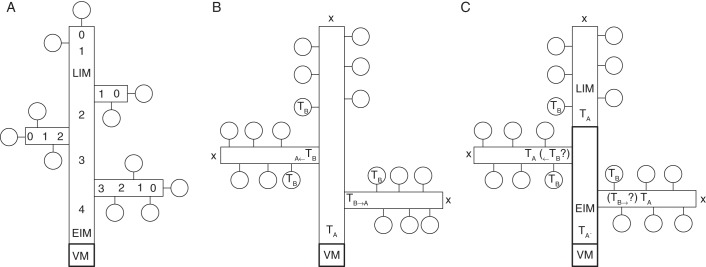

The decrease of meristem size can also be seen in the development of panicles. Here the AM enlarges only once at the reproductive transition from VM to EIM (producing partial inflorescences) and then continuously diminishes in size until it transforms into the LIM, producing lateral and terminal flowers. In the three case studies, the EIM is always larger than the LIM and no visible transition of the meristematic tissue between the two developmental stages can be detected. Accordingly, lateral primordia diminish their branching potential along the main axis originating partial inflorescences first, and single flowers at the end. This ontogenetic observation is compatible with the proposed evenly veg decline in all shoots of the closed compound inflorescence (Fig. 6A). A gradual diminution of the inflorescence meristem after one single enlargement can also be seen in the conjunct inflorescences of Gundelia (Claßen-Bockhoff et al., 1989), Panicum (Reinheimer et al., 2005), Ixora (Chen et al., 2003), Hydrangea (Uemachi et al., 2006; Collet, 2011), Cornus (Feng et al., 2011) and Chenopodium (Gifford and Tepper, 1961).

Fig. 6.

Schematic qualitative diagrams of the ontogeny of the compound inflorescences studied here. (A) Schematic diagram of the development of conjunct inflorescences (panicles and derivate). There is a single transition from the vegetative (VM) to the early inflorescence meristem (EIM). Numbers represent the plastochrones before the shoot apical meristem merges into a terminal flower. Since the diminution is correlated with a gradual decrease in size of the meristem (see Figs 2–4), no discrete morphological distinction can be made between EIM and the flower-producing LIM. (B) Schematic diagram of the development of compound racemes according to the transient model (Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). The model considers a main axis (TA) that produces lateral shoots (TB) which either directly convert into lateral flowers (distal part) or revert to the state of the main axis (TB → TA; proximal part) giving rise to ramification in the inflorescence. Crosses symbolize the absence of terminal flowers. (C) Schematic diagram of the development of disjunct inflorescences (compound racemes and derivatives). The shoot apical meristem experiences the reproductive transition from VM to the EIM which is then characterized with the TA' state. After a second enlargement the EIM gives rise to the LIM, characterized by the state TA and capable of producing lateral flowers (state TB). Hence this second enlargement originates the terminal raceme. Correspondingly, further lateral products of the EIM in TA' state result in shoots in TA state (equivalent to LIM) thus forming lateral racemes. In contrast to the transient model depicted in (B), the relevant transition occurs in the main axis itself. How far at the same time in the lateral shoots a ‘regressive’ transition (TB → TA) occurs, as proposed by the transient model, remains unexplored. Because of the occurrence of two enlargements of the shoot apical meristem, a morphological distinction between EIM and LIM is possible, differing from conjunct inflorescences (A). Circles, Flowers; vertical rectangle, main axis; horizontal rectangles, lateral axes; crosses, absence of terminal flowers.

On the other hand, the ontogeny of compound racemes differs from the former in one relevant point: in all cases studied the EIM is smaller than the LIM. This means that in compound racemes the AM enlarges twice during inflorescence ontogeny: first, by the reproductive stimulus, and then by merging from EIM to LIM. Thus, the AM that produces lateral racemes (EIM) differs from the meristem which produces lateral flowers (LIM), which adequately explains the disjunct morphology of the inflorescence. Contrary to this, the transient model postulates a constant and homogenous main axis in ‘A’ state that produces transient lateral meristems that revert from ‘B’ to ‘A’ state in proximal lateral primordia (Fig. 6B; Prusinkiewicz et al., 2007). However, we found ontogenetic evidence for a transient state of the main axis when transforming from EIM to LIM. Here we have called these states A' and A (Fig. 6C). While the A state of the main axis corresponds to the terminal raceme, the A′ state corresponds to the main axis giving rise to racemes in lateral and terminal position (Fig. 6C). From this viewpoint, the disjunct morphology of compound racemes is primarily based on the existence of two qualitative states of the AM of the main axis during inflorescence development. How far lateral meristems would also behave in a transient manner in disjunct inflorescences reverting from a putative ‘B’ to ‘A’ state (Fig. 6C) would demand further observation.

The finding that the meristematic size increases two times during inflorescence ontogeny is rarely shown and so far it was never explicitly described. The main reason may be that not many disjunct compound inflorescences have been studied in detail. However, these events can be also observed in the disjunct compound inflorescences of Zea (Sundberg et al., 1995; Sundberg and Orr, 1996; Kieffer et al., 1998) and in the compound raceme of Brassica (Kieffer et al., 1998).

Morphological consequences

Interestingly, the interplay of the two key ontogenetic processes, the intensity and the timing of AM size variation, explain the genesis of the four basic inflorescence patterns, i.e. simple and compound racemes, botryoids and panicles (Claßen-Bockhoff and Bull-Hereñu, 2013).

The finding that panicles and compound racemes differ in their development from the beginning and throughout their genesis has consequences for the interpretation of inflorescence evolution. In the traditional inflorescence literature, compound racemes and panicles are meant to be evolutionarily related and can be transformed into each other by some structural changes. The transition from panicles to compound racemes would for instance include ‘truncation’ (loss of the terminal flower), ‘homogenization’ (acquisition of disjunct morphology) and ‘racemization’ (uniformity in flowering direction; Sell, 1981; Kusnetzova, 1988; Claßen-Bockhoff, 2001). These steps, formally conceived by comparing the phenotype of the mature inflorescence types, are thought to act independently in evolution. However, we have shown that the ontogeny of panicles and compound racemes differs profoundly, and that probably all the differences between these two types arise simultaneously as consequences of different ontogenies.

Concluding remarks

We have shown that principles of the transient model for inflorescence architecture find partial support in ontogeny, being the veg factor related to the size of the meristem in closed inflorescences. However, we further found evidence that a biphasic kinetics of the development of the AM would be the departing explanatory evidence for the disjunct morphology of compound racemes. The mechanisms behind this double enlargement of the AM during inflorescence ontogeny remain to be addressed by future works.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful for the comments of two anonymous reviewers and the helpful advice of the Handling Editor, which improved the clarity of this manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alvarez J, Guli CL, Yu XH, Smyth DR. Terminal flower: a gene affecting inflorescence development in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 1992;2:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bull-Hereñu K, Claßen-Bockhoff R. Ontogenetic course and spatial constraints in the appearance and disappearance of the terminal flower in inflorescences. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2011;172:471–498. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak M, Seleznyova AN, Prusinkiewicz P, Hanan J. Towards aspect-oriented functional–structural plant modelling. Annals of Botany. 2011;108:1025–1041. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claßen-Bockhoff R. Plant morphology: the historic concepts of Wilhelm Troll, Walter Zimmermann and Agnes Arber. Annals of Botany. 2001;88:1153–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Claßen-Bockhoff R, Bull-Hereñu K. Towards an ontogenetic understanding of inflorescence diversity. Annals of Botany. 2013;112:1523–1542. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claßen-Bockhoff R, Froebe HA, Langerbeins D. The inflorescence of Gundelia tournefortii L. (Asteraceae) Flora. 1989;182:463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Chu CY, Huang MC. Inflorescence and flower development in Chinese Ixora. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 2003;128:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Collet T. Architektur und Entwicklung floral-differenzierter Blütenstände in der Familie der Hydrangeaceae. Diploma thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität. 2011 Mainz, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK. Disentangling confusions in inflorescence morphology: patterns and diversity of reproductive shoot ramification in angiosperms. Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 2010;48:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Feng C-M, Xiang Q-Y, Franks RG. Phylogeny-based developmental analyses illuminate evolution of inflorescence architectures in dogwoods (Cornus s.l., Cornaceae) New Phytologist. 2011;191:850–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EM, Tepper HB. Ontogeny of the inflorescence in Chenopodium album. American Journal of Botany. 1961;48:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler MG, Jonsson H. Modelling meristem development in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2007;10:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer M, Fuller MP, Jellings AJ. Explaining curd and spear geometry in broccoli, cauliflower and ‘romanesco’: quantitative variation in activity of primary meristems. Planta. 1998;206:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kusnetzova TV. Angiosperm inflorescences and different types of their structural organization. Flora. 1988;181:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Prenner G, Vergara-Silva F, Rudall PJ. The key role of morphology in modelling inflorescence architecture. Trends in Plant Science. 2009;14:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Runions A. Computational models of plant development and form. New Phytologist. 2012;193:549–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Erasmus Y, Lane B, Harder LD, Coen E. Evolution and development of inflorescence architectures. Science. 2007;316:1452–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.1140429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheimer R, Pozner R, Vegetti AC. Inflorescence, spikelet, and floral development in Panicum maximum and Urochloa plantaginea (Poaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2005;92:565–575. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser R. Plastochrone ratio and leaf arc as parameters of a quantitative phyllotaxis analysis in vascular plants. In: Jean RV, Barabé D, editors. Symmetry in plants. Singapore: World Scientific; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sell Y. Die komplexen racemösen Infloreszenzstrukturen bei einigen Myrtalen. Beiträge zur Biologie der niederen Pflanzen. 1981;56:381–414. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S, Meekswagner DR. A mutation in the Arabidopsis TFL1 gene affects inflorescence meristem development. The Plant Cell. 1991;3:877–892. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.9.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg MD, Orr AR. Early inflorescence and floral development in Zea mays land race Chapalote (Poaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1996;83:1255–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg MD, Lafargue C, Orr AR. Inflorescence development in the standard exotic maize, argentine popcorn (Poaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1995;82:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Szczesny T, Routier-Kierzkowska AL, Kwiatkowska D. Influence of clavata3-2 mutation on early flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana: quantitative analysis of changing geometry. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:679–695. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troll W. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1964. Die Infloreszensen. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SC. Pseudoracemes in papilionoid legumes: their nature, development, and variation. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1987;95:181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Uemachi T, Kurokawa M, Nishio T. Comparison of inflorescence composition and development in the lacecap and its sport, hortensia Hydrangea macrophylla (Thunb.) Ser. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science. 2006;75:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Weberling F. Stuttgart: Ulmer; 1981. Morphologie der Blüten und Blütenstände. [Google Scholar]