Background: Chaperonins like the GroEL-GroES complex facilitate protein folding in the cell.

Results: Substrate proteins are captured by the open, trans ring of the GroEL-ATP-GroES complex and are partially unfolded.

Conclusion: Maximally efficient folding requires repeated cycles of substrate protein unfolding by the GroEL-GroES complex.

Significance: Establishing how substrate proteins are processed by chaperonins is essential for understanding how proteins fold inside cells.

Keywords: Chaperone Chaperonin, Molecular Chaperone, Protein Dynamics, Protein Folding, Protein Misfolding, GroEL, Hsp60

Abstract

A key constraint on the growth of most organisms is the slow and inefficient folding of many essential proteins. To deal with this problem, several diverse families of protein folding machines, known collectively as molecular chaperones, developed early in evolutionary history. The functional role and operational steps of these remarkably complex nanomachines remain subjects of active debate. Here we present evidence that, for the GroEL-GroES chaperonin system, the non-native substrate protein enters the folding cycle on the trans ring of the double-ring GroEL-ATP-GroES complex rather than the ADP-bound complex. The properties of this ATP complex are designed to ensure that non-native substrate protein binds first, followed by ATP and finally GroES. This binding order ensures efficient occupancy of the open GroEL ring and allows for disruption of misfolded structures through two phases of multiaxis unfolding. In this model, repeated cycles of partial unfolding, followed by confinement within the GroEL-GroES chamber, provide the most effective overall mechanism for facilitating the folding of the most stringently dependent GroEL substrate proteins.

Introduction

Molecular chaperones assist in the folding of proteins that, on their own, have little chance of achieving their native conformation (1, 2). One of the most studied molecular chaperone systems is the GroEL-GroES chaperonin system of Escherichia coli (3–5). GroEL is a tetradecamer of 57-kDa subunits, arranged as two stacked, seven-membered rings, with each ring containing a large, open, solvent-filled cavity (6). The cavity-facing surface of the uppermost domain of each subunit (the apical domain) is lined with hydrophobic amino acids that tightly bind substrate proteins that are neither folded nor random coil (so called “non-native” proteins) (7). Efficient folding of many proteins requires that they then be enclosed within a cavity formed by GroEL and the smaller, ring-shaped co-chaperonin GroES (8–11). Binding of GroES to a GroEL ring with a captured substrate protein seals the GroEL cavity and results in the release of the substrate protein into an enlarged GroEL-GroES chamber (a cis complex). Folding is initiated upon release of the substrate protein into the GroEL-GroES cavity and continues within this protected space for a brief period, until the cavity is disassembled and the protein, folded or not, is ejected back into free solution (9–13). In general, highly GroEL-dependent substrate proteins must go through repeated rounds of assisted folding, because only a small fraction of the molecules fully commit to their native conformation during any single round (12–14).

To function as a folding machine, GroEL must execute a dynamic cycle of substrate protein binding and release, which is ultimately driven by ATP hydrolysis (3–5). In the currently accepted model of the GroEL reaction cycle, non-native substrate proteins only enter the cycle on the trans ring of a GroEL-GroES complex containing ADP in the cis ring (an ADP bullet; Fig. 1a). Subsequent binding of ATP and GroES to the substrate protein-occupied trans ring then encapsulates the bound substrate protein (forming an ATP bullet), while at the same time driving disassembly of the folding cavity left over from the previous reaction cycle. GroEL thus acts as a dynamic two-stroke protein folding machine, with both rings participating in a highly coordinated process of ligand binding and release (8, 15, 16).

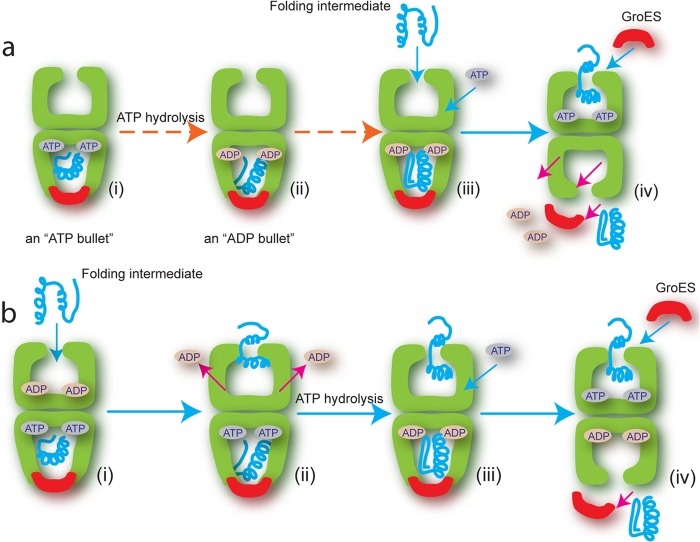

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of conventional and revised reaction sequence for protein entry into the GroEL folding reaction. a, in the conventional model, the reaction begins with the product of the previous cycle: the asymmetric GroEL (green)-ATP-GroES (red) complex (an ATP bullet) contains substrate protein (blue) within the cis cavity (i). ATP hydrolysis results in the GroEL-ADP-GroES substrate-bound complex (an ADP bullet) (ii), which now captures the next non-native substrate protein (Folding intermediate) on the open, nucleotide-free trans ring (iii) (15). ATP binding to the trans ring is required for the next round of GroES binding, substrate encapsulation and folding. Although the order in which ATP and substrate protein bind is unclear, both must bind the trans ring to trigger release of GroES and substrate protein from the cis ring (iv). b, in the revised model, the reaction begins with the asymmetric ATP bullet complex, but with ADP tightly bound to the trans ring (i) (18, 19). Binding of the non-native protein drives ADP off the trans ring (ii). ATP binds the trans ring only after ATP hydrolysis on the cis ring has generated an ADP bullet (iii), a reaction that is inhibited by ADP bound to the trans ring (29). GroES then encapsulates the substrate protein to initiate folding and simultaneously trigger release of GroES and substrate protein from the cis ring (iv).

Many essential aspects of the GroEL reaction mechanism remain poorly defined or controversial. For example, recent work has suggested that non-native substrate protein can bind to the trans ring of an ATP bullet complex, an observation that conflicts with a central assumption of the standard reaction model (17). Other recent work has suggested that ADP release plays a central role in the reaction cycle (18, 19), whereas still other studies have suggested that ATP binds to an open GroEL ring before non-native substrate protein (20). None of these observations are easily reconciled with the standard model of the GroEL reaction cycle. Additionally, how GroEL ultimately stimulates folding of a substrate protein remains a subject of active debate. A variety of mechanisms have been proposed, ranging from the exclusive and passive suppression of protein aggregation to more active models involving the unfolding of misfolded states or the conformational editing of the substrate protein's free energy landscape through spatial confinement within the GroEL-GroES cavity (3–5).

Here we employ a combination of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS),2 FRET, and enzymatic assays to re-examine substrate protein entry into the GroEL reaction cycle. Our results demonstrate that GroEL enforces a specific ligand binding order that ensures efficient assembly of a GroEL-GroES folding chamber containing a non-native protein. The key to this ordered assembly process is the binding of non-native substrate proteins to the trans ring of the ATP bullet (Fig. 1b). Further, we show that this binding sequence ensures that a kinetically trapped folding intermediate of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (RuBisCO) is subjected to two phases of unfolding as it is processed by the GroEL machine: first, capture of the RuBisCO monomer on an open GroEL ring results in binding-induced unfolding, followed by a round of forced unfolding as ATP binds to the RuBisCO-occupied GroEL ring. Both unfolding events occur over multiple spatial axes and, more importantly, appear to enhance the folding efficiency of the cycling chaperonin system beyond what is achievable by simple confinement within the GroEL-GroES cavity alone.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins

Wild-type E. coli GroEL and variants (Cys0 GroEL, D398A GroEL, and SR1) were expressed and purified using previously described methods (21). Wild-type E. coli GroES, wild-type Rhodospirillum rubrum RuBisCO, and the various RuBisCO Cys mutants were expressed and purified as previously described (8, 15, 21, 22).

Refolding and Enzymatic Assays

The refolding of RuBisCO by wild-type GroEL and SR1 was assayed essentially as previously described, with minor modifications (8, 21, 22). RuBisCO was first denatured in acid urea buffer (25 mm glycine-phosphate, pH 2.0, 8 m urea; 5 μm final concentration) and then diluted 50-fold into refolding buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 5 mm KOAc, 10 mm Mg(OAC)2, and 2 mm DTT) containing either GroEL or SR1. Folding was initiated (t = 0) by the addition of GroES and ATP, and the samples were then maintained at indicated temperatures using a high precision temperature block (Boekel Scientific TropiCooler 260014). For wild-type GroEL, 50-μl samples were removed at 10–12 discrete time points over the course of 30 min and quenched with hexokinase and glucose to halt the GroEL reaction and stop folding. The samples were then assayed for RuBisCO activity, as previously described (8, 22). For SR1 refolding assays, 50-μl samples were removed at 10–12 discrete time points over the course of 30 min and placed into prechilled tubes at 4 °C containing 12.5 mm EDTA. Incubation at low temperature in the presence of EDTA causes rapid dissociation of the SR1-ADP-GroES complex and release of the RuBisCO monomer, halting the folding reaction (8, 23, 24) (see Fig. 5). Following a 10-min incubation at 4 °C, the samples were returned to 23 °C, supplemented with 50 mm Mg(OAc)2, and assayed for RuBisCO activity as previously described (8). For all refolding experiments, assays were replicated three to five times at each temperature. The observed folding rate constant for each replicate was determined by fitting the experimental data to a single exponential rate law using either Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR) or Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Rate constants for all replicates at a given temperature were then averaged to yield a final, average folding rate constant and associated experimental errors.

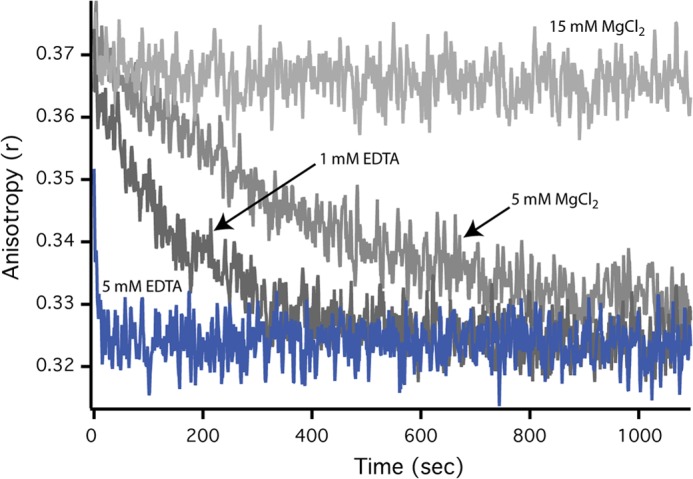

FIGURE 5.

Disassembly of SR1-GroES complex and release of substrate protein is fast at 4 °C with EDTA. The dissociation rate of the SR1-GroES complex under different conditions was examined by following the rate of release of an encapsulated substrate protein. First, acid-denatured GFP (500 nm) was bound to SR1 (2.5 μm). The complex was then mixed with ATP (2 mm) and GroES (10 μm), followed by incubation of the sample at 25 °C for 5 min. SR1-GroES complexes containing folded and fluorescent GFP were purified away from free GFP using gel filtration chromatography as previously described (8). Samples of the purified SR1-GroES-GFP complex were then incubated at 4 °C in the presence or absence of EDTA and MgCl2 to determine the rate of complex disassembly and substrate protein release from an artificially disrupted SR-GroES complex. GFP release into free solution was observed as a decrease in steady state fluorescence anisotropy (15).

ATPase rates were determined with a coupled enzyme assay (18). Each reaction contained 1 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 10 units/ml pyruvate kinase, 0.2 mm NADH, and 10 units/ml l-lactate dehydrogenase. GroEL and GroES were diluted to 250 and 500 nm oligomer, respectively, in reaction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT) that was preincubated at the indicated temperature. Reactions were initiated by addition of ATP to 2 mm. Changes in absorption at 340 nm were monitored for 5 min immediately after the addition of ATP in a thermally jacketed spectrophotometer. The observed ATP hydrolysis rates were corrected for small changes in base-line signal at the different assay temperatures, when observed.

Labeling of RuBisCO with Fluorescent Dyes

Various RuBisCO Cys mutants, as well as GroEL315C and GroES98C, were labeled as previously described (15, 21, 22). The thiol-reactive dyes used in this study were: 5-iodoacetamidofluorescein (F) and 5-(2-acetamidoethyl) aminonaphthalene-1-sulfonate (ED). All reactive dyes were obtained from Invitrogen and were prepared fresh from dry powder in anhydrous dimethyl formamide immediately prior to use. The extent and specificity of dye conjugation was confirmed as previously described (21–22, 25).

Complex Formation between RuBisCO and GroEL-GroES Bullet trans Rings

The binding of RuBisCO to the trans ring of a GroEL-GroES complex was conducted by first creating two asymmetric chaperonin complexes: GroEL-ADP-GroES and ELD398A-ATP-GroES complex (21). Samples of GroEL or ELD398A (7 μm), GroES (8.4 μm), and ATP (250 μm) were mixed in 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 5 mm KOAc, 10 mm Mg(OAc)2, 2 mm DTT and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The asymmetric complex was then diluted to the desired concentration and supplemented with fluorescent, acid-urea-denatured RuBisCO (58F), and the sample was incubated for 10 min at 25 °C to allow trans ring binding. The symmetric ELD398A-ATP-GroES2 “football” complex was formed following the same basic procedure, using a 2-fold increase in the GroES concentration (16.8 μm). The resulting symmetric complex was then diluted and incubated with acid-urea-denatured RuBisCO in the same manner outlined above, to examine substrate protein binding efficiency to this complex. The samples were loaded onto a Superose 6 gel filtration column, and the elution profile followed with an in-line fluorescence detector. The column running buffer was the same as the incubation buffer used for complex formation but contained 10 μm ADP. The binding efficiency was determined from the integral of the fluorescence RuBisCO that co-migrated at the GroEL peak.

Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy

FCS was used to monitor the folding kinetics of non-native, fluorescently labeled Rubisco (58F) in the presence of cycling GroEL, GroES, and ATP over the course of 20 min. A cycling mixture of GroEL (100 nm), GroES (200 nm), and ATP (1 mm) was prepared in refolding buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 5 mm KOAc, 10 mm Mg(OAC)2, and 2 mm DTT) and incubated for 5 min at 25 °C to allow the system to achieve a steady state. Samples of unlabeled RuBisCO and fluorescein-labeled RuBisCO were first denatured for 30 min in 8 m acid-urea buffer and then mixed together at a ratio of 19:1 (unlabeled:labeled) to create a denatured RuBisCO stock containing 5% Rub58F. Denatured RuBisCO was then rapidly diluted 100-fold into the cycling GroEL-GroES mixture to a final concentration of 100 nm RuBisCO monomer (95 nm unlabeled plus 5 nm labeled final concentration). A 10-μl drop of the final mixed sample was then placed on a BSA-blocked coverslip attached to the microscope objective of a custom-built confocal microscope (26) and covered with a humidified chamber to prevent evaporation. The typical dead time to the first observation was less than 10 s. Autocorrelation curves were collected every 30 s for 20 min, and the full experiment was repeated five times. Autocorrelation curves were normalized in mean amplitude between 1 × 10−5 and 1 × 10−4 s for purposes of co-adding data. As a calibration standard, the autocorrelation curve for RuBisCO fully bound to the trans ring of a GroEL-ADP-GroES complex was determined by mixing denatured RuBisCO with an excess of the ADP bullet complex. The instrument response of the microscope was characterized by measurements of freely diffusing tetramethylrhodamine in aqueous buffer and indicated that the beam waist diameter was 0.4 microns with a lateral to axial ratio of 1:3.

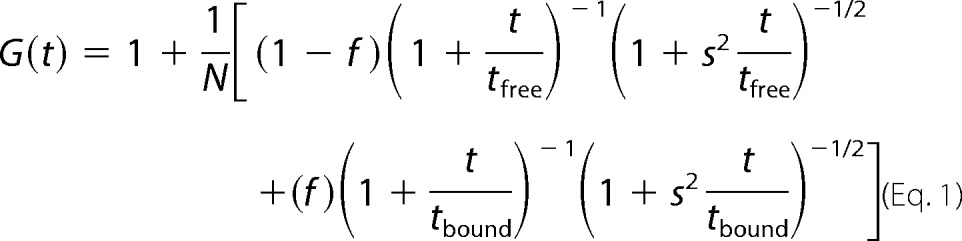

The fluorescence autocorrelation function corresponding to two mixed species where the fraction bound was represented by f can be expressed as follows:

|

Here, N is the overall particle number in the excitation volume, tfree and tbound represent the diffusion time through the excitation spot for the free and bound species, and s is a beam structure factor defined as the excitation spot waist along the optical axis divided by the waist size in the lateral plane (assumed circularly symmetric about the optical axis). A single component fit of the autocorrelation data from the calibration dye (tetramethylrhodamine) determined this structure factor to have the value 3.

The rate of native RuBisCO dimerization was observed to be slow under the conditions of the FCS assay (not shown), so that the product of the folding reaction at any time point was likely to be a mixture of uncommitted monomer, committed monomer, and dimer. Although there was no evidence to indicate that the standard two-component model curves were invalid, because the cycling RuBisCO system would not be formally well described by a two-component model, we compared two independent analysis methods to determine the fraction of RuBisCO bound as a function of time: the standard two-component fit analysis and a “half-amplitude” analysis that was less reliant on a autocorrelation model fit. The results of both techniques were statistically consistent. In the half-amplitude method, we used the same normalized autocorrelation data as was used in the two-component fit except that the time of half-amplitude crossing time was found without imposing a model fit. For a standard single component autocorrelation curve, this time roughly corresponded to the mean diffusion time of a particle through the excitation beam.

Kinetic Simulation of Steady State GroEL-GroES Reaction Cycle

We modeled the cycling GroEL-GroES system in two ways: 1) a classical cycle dominated by asymmetric complexes (15, 27) and 2) an updated cycle explicitly incorporating symmetric football complexes and the role played by ADP dissociation in trans ring (18, 19, 28–30). In all cases, values of the rate constant for each transition were taken from the literature. The Monte Carlo-based, stochastic simulation package CKS (IBM) was employed for the simulation.

Stopped Flow Fluorescence and Data Analysis

Stopped flow experiments were performed essentially as previously described (22) using an SFM-400 rapid mixing unit (BioLogic; Claix, France) equipped with a custom designed, two-channel fluorescence detection system. For intramolecular FRET measurements with labeled RuBisCO, the time-dependent change in donor side FRET efficiency of the labeled RuBisCO monomer was extracted from matched sets of donor-only and donor-acceptor stopped flow experiments as previously described (22). The lifetime of the GroEL-GroES complex at different temperatures was determined from the time-dependent change in donor side FRET efficiency following the rapid addition of a large excess of unlabeled GroES to a sample containing donor-labeled GroEL complexed with acceptor labeled GroES. Labeled GroEL 315ED (donor) and GroES 98F (acceptor), both at 300 nm oligomer, were mixed with 5 mm ATP and an ATP regeneration system consisting of 5 mm creatine phosphate, and 30 units/ml creatine kinase. Following thermal equilibration of the sample in a stopped flow sample syringe, the cycling GroEL-GroES mixture was then rapidly mixed (1:1) with a 6 μm unlabeled wild-type GroES. For all stopped flow experiments, the refolding buffer described above was used, but the KOAc concentration increased to 100 mm. Matched sets of donor-only and donor-acceptor stopped flow experiments were employed as previously described (15, 25). Fitting of experimental data were accomplished with either Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR) or Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

RESULTS

We have reproduced the basic observation that non-native substrate protein can bind to the trans ring of an ATP bullet created from the hydrolysis deficient GroEL mutant D398A (EL398A), first noted by the Taguchi group (17). When the GroES:EL398A ratio is 1:1, non-native R. rubrum RuBisCO binds as well to the ATP-bullet trans ring as to the ADP-bullet trans ring (Fig. 2a). Because the exposed trans ring of the ATP bullet is the first point in the GroEL reaction cycle where an open ring is exposed (Fig. 1), these results imply that that non-native substrate most likely enters the GroEL reaction cycle on the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex under standard, steady state cycling conditions.

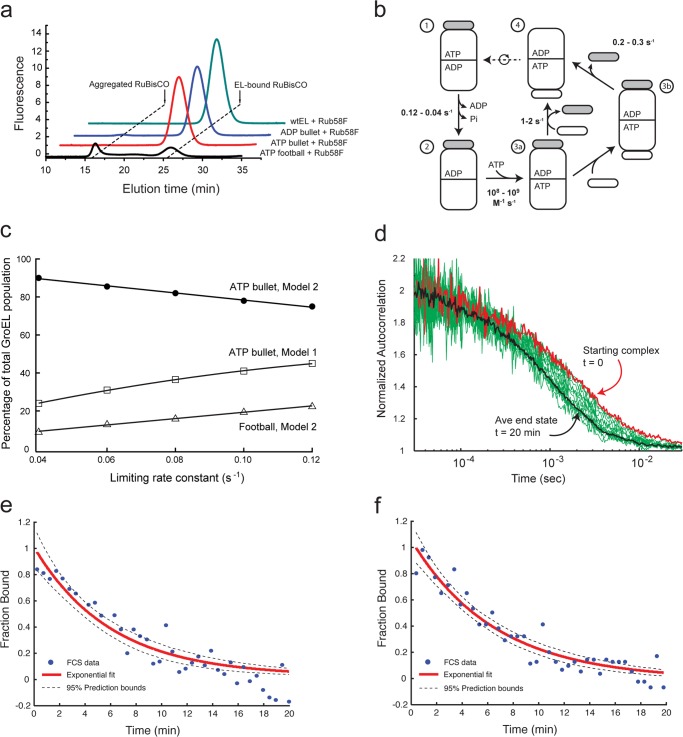

FIGURE 2.

Capture of non-native RuBisCO on the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex. a, non-native RuBisCO binds efficiently to the trans ring of an ATP bullet complex made with the hydrolysis-deficient GroEL mutant D398A. A fluorescent variant of RuBisCO (58F) was denatured and mixed with different complexes made from wild-type (wt) GroEL or D398A. Shown is binding of non-native RuBisCO to the trans ring of a wild-type ADP bullet complex (ADP bullet) and the trans ring of a D398A ATP bullet complex (ATP bullet). RuBisCO binding to the D398A in the presence of ATP and excess GroES, conditions where this mutant efficiently forms symmetric D398A-ATP-ES2 complexes (ATP football) (17), is also shown. Stable binding was monitored by HPLC gel filtration chromatography and in-line fluorescence detection. b, an updated steady state GroEL reaction cycle in the presence of excess GroES and absence of non-native substrate protein. The kinetically dominant steps of the cycle, along with their associated rate constants, are shown. The transition from steps 1 to 2 involves both ADP release from the trans ring and ATP hydrolysis in the cis ring. The intrinsic rate of ATP hydrolysis in the cis ring occurs at a maximal rate of 0.12 s−1 (27), but this turnover is restricted by the rate of ADP release from the trans ring, an event that proceeds at an average rate of 0.04 s−1 in the absence of non-native substrate protein (18, 19, 28, 29). The subsequent binding of ATP to the open trans ring is approximately diffusion-limited (steps 2 to 3a) (15, 21). The transition to a new ATP bullet complex can progress along either of two paths. In steps 3a to 4, release of the previously bound GroES (gray) occurs at essentially the same rate that a new GroES binds to the ATP-bound ring (15). Alternately, release of the prior GroES can be slower than the rate of new GroES binding, resulting in a symmetric football intermediate, which subsequently decays to an asymmetric complex (30). c, kinetic simulation of the GroEL reaction cycle, showing the fractional population ATP bullets under conditions of steady state ATP turnover across a range of values of the rate-limiting step. The simulation was carried out for two reaction schemes: 1) a classical cycle dominated by asymmetric complexes (ATP bullet, Model 1) (15, 27) and 2) the updated cycle illustrated in b (ATP bullet, Model 2). The fraction of symmetric football complexes derived from the updated cycle in b is also shown (Football, Model 2). d, the extent of RuBisCO binding to wild-type GroEL during a fully active reaction cycle was examined by FCS. Wild-type GroEL and GroES were mixed at a ratio of 1:2, supplemented with excess ATP (1 mm) and incubated for 1–2 min. Non-native, fluorescent RuBisCO (58Alexa488) was added rapidly, and the extent of RuBisCO binding was examined as a function of time by FCS. Twenty minutes of autocorrelation data (five repeats) were collected and fit to a two-component model defined by the GroEL-bound and the final unbound state of RuBisCO after 20 min. Only if 100% of the RuBisCO is bound to a GroEL bullet complex would the measured fraction bound reach a value of 1; similarly, only after all RuBisCO remained unbound would the measured fraction bound reach a value of zero. Experimental autocorrelation curves are shown (green), with the autocorrelation curve of a stable reference complex between an ADP bullet and RuBisCO (red). At ∼20 min, there was no change detected in the autocorrelation curve: an average of three curves from 20 to 30 min represents the end point (black). e, the observable decrease of the average fraction bound is well fit by a single exponential decay model with a half-time of 5.5 min (95% bounds of 4.7 and 6.7 min; black dashed line). Extrapolation of the average fraction bound to the start of the folding reaction implies all or nearly all RuBisCO monomers are efficiently captured upon addition of the non-native protein. f, the mean diffusion time of RuBisCO at various time points was extracted from the half-amplitude of the experimental autocorrelation curves. The mean diffusion time, as a function of folding time, is shown. The observed decrease in observed diffusion time, indicative of the productive folding and release of RuBisCO monomers into free solution, is well fit by a single exponential decay model with a half-time of 4.6 min (95% bounds of 4.0 and 5.3 min; black dashed line). Extrapolation of the mean diffusion time to the start of the folding reaction indicates that the RuBisCO monomers were efficiently captured upon addition of the non-native protein.

RuBisCO Enters the GroEL Reaction Cycle on the ATP Bullet trans Ring

Although suggestive, experiments that show RuBisCO binding to the trans ring of a D398A ATP bullet suffer from a significant weakness: these experiments assume that the trans ring of the EL398A-GroES-ATP complex behaves like a wild-type GroEL ring. However, because EL398A quantitatively forms symmetric football complexes at concentrations of ATP and GroES where wild-type GroEL does not (17), it remains possible that non-native RuBisCO binding to the trans ring of D398A is an artifact of the altered allostery that also leads to efficient football formation. To test this possibility, we developed an alternate approach to measuring the binding of non-native RuBisCO to GroEL, in the presence of GroES and under the more physiologically realistic conditions of cycling, steady state ATP hydrolysis. Under these conditions, the GroEL tetradecamer population is dominated by asymmetric, bullet-shaped GroEL-GroES complexes (15, 31, 32). To examine the distribution of ATP versus ADP bullets in greater detail, we conducted a series of kinetic simulations using established values of the limiting transitions of the GroEL reaction cycle (Fig. 2, b and c). When the cycle is modeled using classical descriptions (Model 1) (15, 27), ∼25–50% of the GroEL tetradecamers are present as ATP bullets. However, when a more accurate model of the reaction cycle is employed (Model 2) (Fig. 2b), the GroEL population is dominated (80–90%) by ATP bullet complexes, with the ADP bullet population representing less than 10% of the total population. Notably, this updated reaction scheme predicts that 10–20% of the GroEL complexes should be found as symmetric football complexes, consistent with cryoEM observations of the cycling GroEL-GroES system (32).

The kinetic simulations allow a set of specific predictions to be made about how much non-native RuBisCO could initially be captured by a cycling GroEL-GroES reaction. With the updated cycle shown in Fig. 2b, and assuming RuBisCO exclusively enters the GroEL reaction cycle on the trans ring of an ADP bullet, a cycling mixture of GroEL and GroES could initially bind only 10–20% of the non-native RuBisCO. Alternately, exclusive entry of non-native protein on the trans ring of the ADP bullet using the classical reaction cycle predicts that at most 50–75% of the RuBisCO could be initially bound. However, if non-native RuBisCO can also bind the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex, the cycling GroEL-GroES sample should capture the entire RuBisCO monomer population within seconds of mixing.

To measure the fraction of non-native RuBisCO initially bound by the cycling GroEL-GroES system, we developed a kinetic assay based on FCS. Because the average diffusion time of a RuBisCO monomer bound to a GroEL-GroES complex is much longer than that of the free monomer, FCS provides an ideal method for examining the fraction of non-native RuBisCO bound by cycling GroEL-GroES (Fig. 2, d–f). Fluorescently labeled, non-native RuBisCO momomers were generated as previously described (15, 22, 25). When a cycling sample of GroEL, GroES, and ATP is mixed with non-native, fluorescent RuBisCO at a stoichiometry of 1:1 (GroEL:RuBisCO), we observe a substantial shift in the FCS curve of the RuBisCO monomer (Fig. 2d, red followed by green). With time, the curve moves to shorter average correlation times, indicative of productive folding and release of the committed RuBisCO into free solution. Within ∼20 min, little additional shift in the average correlation time of the fluorescent RuBisCO is detectable (Fig. 2d, black line). Direct fitting of the observed FCS curve to a two-component model (Fig. 2e) allowed extraction of the relative fractions of bound and free RuBisCO, as well as an apparent half-time (t½) for the folding commitment of the RuBisCO monomer of ∼5 min, in excellent agreement with previous measurements of GroEL-mediated RuBisCO folding (8, 22, 23, 33). An independent analysis of the observed FCS curves based on measurement of the apparent mean diffusion times yielded identical results (Fig. 2f). Importantly, in both cases, extrapolation of the bound RuBisCO fraction to zero time shows that the entire RuBisCO population was captured at the beginning of the reaction (Fig. 2, e and f). These observations strongly suggest that: 1) non-native RuBisCO can enter the GroEL reaction cycle on the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex and 2) the trans ring of a EL398A-GroES-ATP complex is, in fact, a good proxy for the trans ring of a wild-type GroEL-GroES ATP bullet.

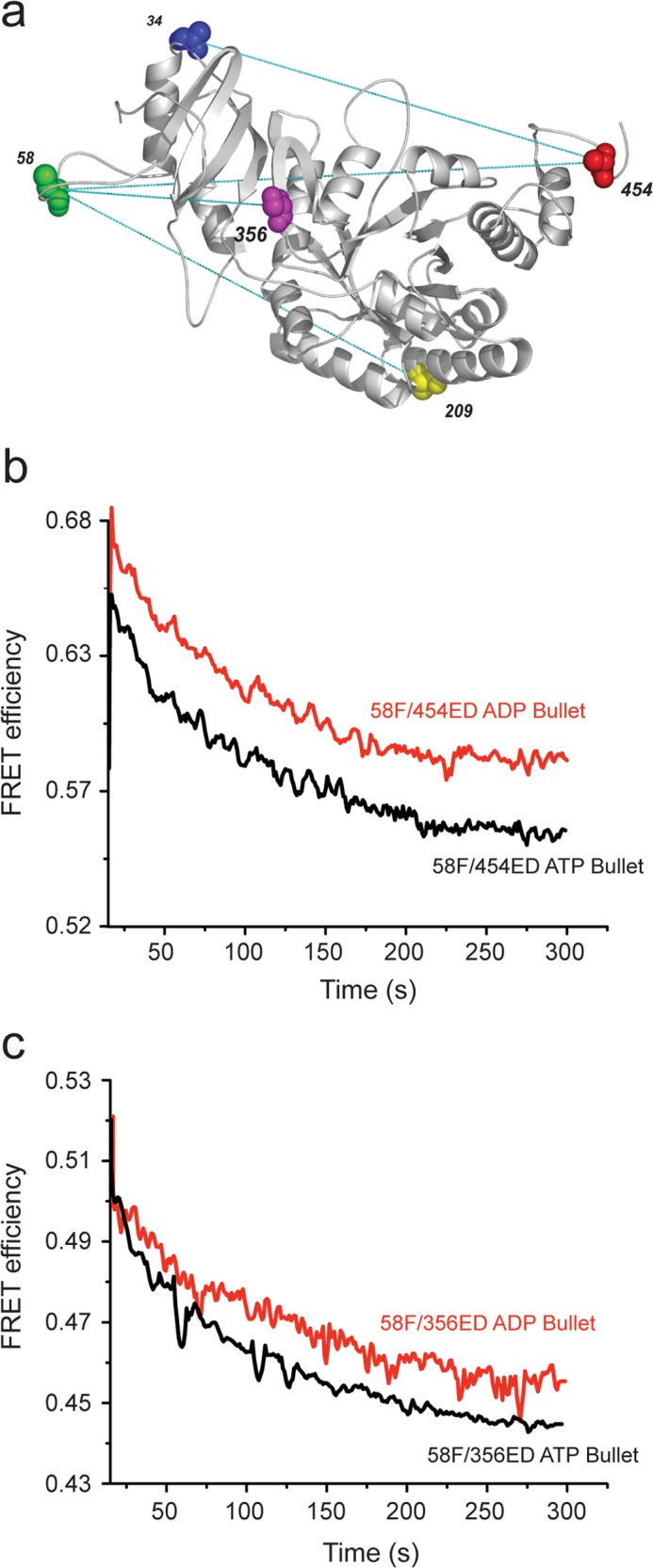

Multiaxis Unfolding of RuBisCO by the GroEL trans Ring

We next examined whether binding of a non-native protein to the trans ring of an ATP bullet induces the same structural alterations in the substrate protein that occur upon binding to an ADP bullet trans ring. Previous studies have demonstrated that when denatured RuBisCO is diluted from either GdmHCl, acid, or acid-urea, the protein rapidly collapses to a misfolded, monomeric state that is highly aggregation prone at 25 °C in the absence of GroEL (12, 22, 33, 34). Additionally, we have shown that this collapsed, non-native RuBisCO monomer is partially unfolded following capture by the trans ring of the ADP bullet complex (21). These conclusions were based in part upon an intramolecular FRET assay that employed homogeneous and site-specific modification of two surface-exposed Cys residues in RuBisCO (amino acid positions 58 and 454) with small, exogenous fluorescent probes (fluorescein iodoacetamide (F) and 5-(2-acetamidoethyl)aminonaphthalene-1-sulfonate (ED); Fig. 3a).

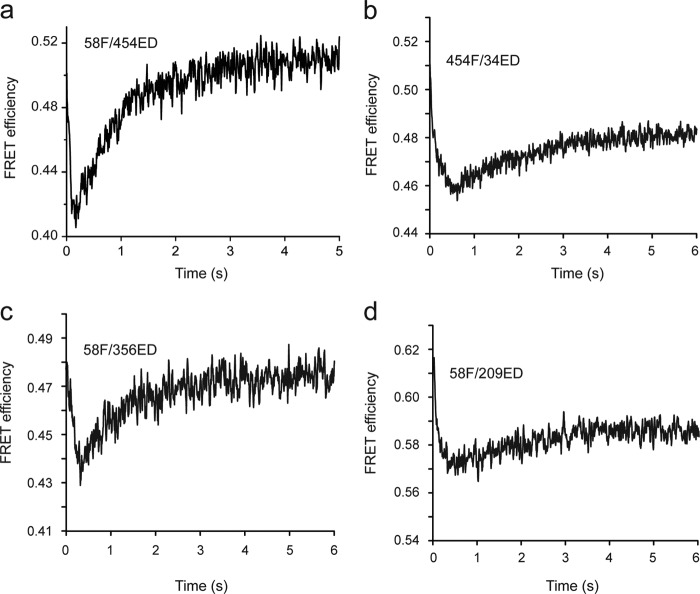

FIGURE 3.

Interaction with the trans ring of an ATP bullet results in binding-induced unfolding of the RuBisCO intermediate across multiple spatial axes. a, design of a multiple-site FRET network for examining the conformation of RuBisCO during a GroEL-dependent folding cycle. The structure of one monomer of the native RuBisCO dimer (Protein Data Bank code 9RUB) is shown. Only one of the endogenous cysteine residues is exposed on the surface of native RuBisCO (C58). Four additional, surface-exposed positions were selected as dye attachment sites using a structure-based design strategy (25). The endogenous amino acids at each site were changed to Cys, both individually and in combination. The reactivity of each engineered Cys residue toward thiol-alkylating dyes was measured, and the different sites were matched so that double-Cys variants could be uniquely and selectively labeled with either a donor or acceptor dye at a specific position (22). Sites successfully paired in this fashion, and where all single and double dye-labeled variants cause no detectable perturbation to the stability or folding of the RuBisCO protein, are shown with connecting lines between the paired sites. b and c, the conformation of the non-native RuBisCO monomer upon binding to a GroEL-GroES complex was monitored by intramolecular FRET. RuBisCO variants labeled at two positions, with the donor dye (ED) and the acceptor dye (F), were denatured and rapidly mixed (to 50 nm final concentration) with 100 nm samples of either ADP bullets made from wild-type GroEL or ATP bullets made from D398A GroEL. Upon binding to the trans rings of either the ADP bullet or the ATP bullet, the magnitude of intramolecular FRET decreased, indicative of structural expansion of the RuBisCO monomer. For FRET pairs 58F/454ED (a) and 58F/356ED (b), the extent and rate of binding-induced unfolding of the RuBisCO monomer was essentially the same. Note that under these experimental conditions, initial binding was complete within ∼5 s (15), so that the conformational expansion reported by the decrease in FRET efficiency was a result of structural rearrangement of the captured RuBisCO monomer on the GroEL ring. Because the kinetics of binding-induced unfolding observed with the other FRET pairs, 58F/209ED and 454F/34ED, were very similar to the 58F/454ED and 58F/356ED pairs, the transients for these sites are not shown. However, see Table 1 for details of the observed FRET efficiencies and average separation distance of the dyes for each pair of sites both before and after RuBisCO monomer binding to a GroEL ring.

We find that when 58F/454ED RuBisCO is mixed with an ATP bullet complex, both the extent and rate of conformational expansion of the folding intermediate on the ATP bullet trans ring are very similar to what is observed following binding to the trans ring of an ADP bullet (Fig. 3b). We have now expanded our set of FRET-based structural probes to three additional pairs of sites (58F/356ED, 58F/209ED, and 454F/36ED; Fig. 3a). In every case, we observe a binding-induced expansion of the non-native RuBisCO folding intermediate upon capture by the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex (Fig. 3c and Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Intramolecular FRET distances for RuBisCO bound to GroEL

| RuBisCO variant | State | Distancea |

FRET efficiencyb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steady state | Time resolved | Steady state | Time resolved | ||

| Å | |||||

| 58Fc356EDd (Cα-to-Cα = 38)e | Intermediatef | 40 | 37 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| Apog | >70 | >70 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| transh | 50 | 49 | 0.43 | 0.47 | |

| 58F209ED (Cα-to-Cα = 66) | Intermediate | 40 | 42 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| Apo | 52 | 51 | 0.40 | 0.41 | |

| trans | 42 | 45 | 0.72 | 0.62 | |

| 454F34ED (Cα-to-Cα = 64) | Intermediate | 35 | 36 | 0.72 | 0.69 |

| Apo | 57 | 56 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |

| trans | 41 | 42 | 0.56 | 0.51 | |

| 58F454ED (Cα-to-Cα = 81) | Intermediate | 39 | 37 | 0.67 | 0.73 |

| Apo | 68 | >70 | 0.08 | N/A | |

| trans | 43 | 44 | 0.58 | 0.56 | |

a Distances for all samples were calculated by both steady state and time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy.

b Steady state FRET efficiencies were calculated from an average of at least three experimental replicates of the indicated complex. Time-resolved efficiencies were calculated from the observed fluorescence decay lifetimes as outlined under “Experimental Procedures.” In all cases, the observed experimental variation between replicates and lifetime fitting error was no more than ±5%.

c RuBisCO monomer labeled with fluorescein at amino acid 58.

d RuBisCO monomer labeled with 5-(2-acetamidoethyl) aminonaphthalene-1-sulfonate at amino acid 356.

e Distance (in Å) between α carbons of labeled positions, based on the structure of native R. rubrum RuBisCO (Protein Data Bank code 9RUB).

f RuBisCO monomer stalled in kinetically trapped, non-native intermediate state at 4 °C.

g RuBisCO monomer bound to the ring of otherwise unliganded, tetradecamer GroEL.

h RuBisCO monomer bound to the trans ring of ATP bullet (D398A-GroES-ATP) complex.

The multiaxis expansion of RuBisCO on the trans ring of an ATP bullet supports the idea that structural disruption of kinetically trapped folding intermediates is an important way that GroEL stimulates productive folding (21, 35, 36). However, binding-induced unfolding of RuBisCO on either the ATP or ADP bullet trans ring (Fig. 4) is slow compared with the cycle period of the GroEL-GroES machine under the same conditions (∼10–25 s at 25 °C, depending on the non-native substrate protein load (15, 27)). The detailed nature of these structural rearrangements and the reason for their slow progression are unknown. It is likely that the process resembles the surface denaturation of a protein at a hydrophilic-hydrophobic interface (37–40). Indeed, the structure of the apical domains of the GroEL ring in the substrate protein acceptor state resemble such an interface in many respects (6).

FIGURE 4.

Forced unfolding of the bound RuBisCO intermediate is caused by ATP binding to the GroEL trans ring. Changes in the conformation of the non-native RuBisCO monomer were reported by four different intramolecular FRET pairs: 58F/454ED (a), 454F/34ED (b), 58F/356ED (c), and 58F/209ED (d). Labeled RuBisCO variants were denatured and bound to the trans ring of ADP bullets made from wild-type GroEL (see “Experimental Procedures”). The complex (50 nm) was mixed in a stopped flow with ATP (1 mm), and changes in donor and acceptor fluorescence were monitored as a function of time. The data shown in a for the 58F/454ED pair are drawn from a previous study (21) and are displayed here for reference. In good agreement with these previous measurements, all three additional FRET pairs show a very rapid (t½ = 100–200 ms), ATP-induced forced expansion of the GroEL-bound RuBisCO monomer, followed by a slower (t½ = 1–1.5 s), GroES-induced compaction.

Given the slow rate of binding-induced unfolding compared with the cycle period of GroEL, at best 30–50% of the structural disruption achievable through binding-induced unfolding is likely to occur in the window of time a folding intermediate spends bound to a GroEL-GroES trans ring (Fig. 3). Our previous observations, however, also demonstrated that ATP binding to the RuBisCO-occupied trans ring results in the forced expansion of the RuBisCO monomer as the apical domains move into position to accept GroES (21). This conclusion was based on a single FRET pair (58F/454ED), leaving open the question of how extensively forced unfolding alters the structure of the RuBisCO monomer. We have now re-examined this question, employing our expanded set of FRET pairs in rapid mixing experiments designed to follow the effect of ATP binding to a RuBisCO-occupied trans ring (Fig. 4). In all cases, we observe two phases of change in the average FRET efficiency over the first few seconds of the experiment, with a very rapid drop (∼100–200 ms), followed by a slower rise (1–2 s) in the transfer efficiency. These changes are very similar to the phases of forced unfolding, followed by GroES binding and compaction, which we previously described with the 58F/454ED pair. Thus, as with binding-induced unfolding, forced expansion of the RuBisCO monomer upon ATP binding to a substrate-occupied trans ring is very likely to be distributed over much of the RuBisCO folding intermediate structure.

Repetitive Unfolding of RuBisCO by GroEL Enhances Productive Folding

Although GroEL is capable of disrupting the conformation of a collapsed RuBisCO folding intermediate, the question remains: what is the linkage between this phenomena and enhanced folding? Does the multiaxis expansion of the RuBisCO monomer lead to substantially enhanced folding? Or is it simply an epiphenomenon of substrate binding to, and release from, the multivalent GroEL ring? Our previous observations with RuBisCO and the single-ring GroEL variant SR1 strongly suggested that this structural disruption is, in fact, directly linked to enhanced folding (21). However, these observations were based on an artificially modified GroEL cycle (see Fig. 6a). Because the SR1 variant lacks a second ring, once a protein is encapsulated within the SR1-GroES complex, the intracavity folding window becomes arbitrarily long. In this system, the amount of time allowed for intracavity folding is controlled by treatment of the SR1-GroES complex with mild disrupting conditions (EDTA combined with low temperature), which results in very rapid and efficient release of GroES and the encapsulated protein (Fig. 5) (8, 23, 24). By contrast, with a cycling GroEL-GroES system, the lifetime of the intracavity folding window is limited by the rate of turnover (15). Because this window is much shorter than the rate of folding commitment by the RuBisCO monomer, and because each turn of the GroEL cycle ejects all non-native RuBisCO back into free solution where it cannot fold, the cycling GroEL-GroES system effectively creates a “pulsing” folding cavity, with periods of active folding followed by periods of no folding as uncommitted protein monomers are rebound and re-encapsulated (Fig. 6a).

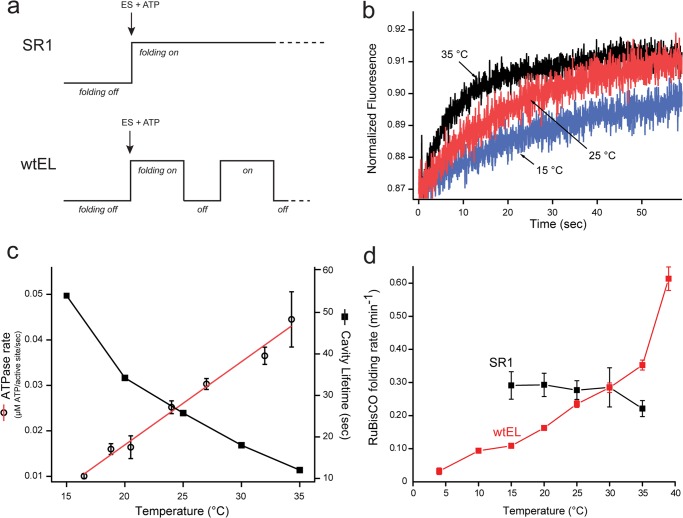

FIGURE 6.

The cycling, wild-type GroEL-GroES system folds RuBisCO at a rate that exceeds the maximum folding rate possible from confinement within the static SR1-GroES cavity. a, schematic summarizing a key difference between assisted protein folding with the single ring GroEL mutant and the wild-type GroEL system. Although a productive SR1-GroES folding cavity can be maintained for an arbitrary duration, wild-type GroEL-GroES cycles, ejecting substrate protein with each cycle (12, 13). At 25 °C, the cycle period is ∼25–30 s when substrate protein is limiting (15, 27). b, the lifetime of the GroEL-GroES complex under conditions of steady state ATP hydrolysis was measured over a range of temperatures, using a previously described FRET assay (15). In the absence of substrate protein, the extent of energy transfer between a donor-labeled GroEL variant (150 nm) and an acceptor-labeled GroES variant (150 nm) in the presence of ATP (2.5 mm) was monitored as a function of time, following addition of excess unlabeled GroES (3 μm). c, lifetime measurements (closed squares) from experiments such as those in b are plotted along with the observed steady state rate of ATP turnover (open circles) by GroEL-GroES in the absence of substrate protein, as a function of temperature. Error bars show the S.D. of n = 3 replicates. d, temperature dependence of RuBisCO folding within the SR1-GroES cavity and in the presence of a fully cycling wild-type GroEL-GroES system. Non-native RuBisCO (100 nm) was bound to either excess SR1 (400 nm) or excess wtEL (400 nm). Samples were then equilibrated at the indicated temperature, and folding was initiated by the addition of a 2-fold molar excess of GroES (800 nm), plus ATP (1 mm). The extent of RuBisCO folding was sampled over the course of 30 min at the indicated temperature. In all cases, the observed refolding kinetics were well described by a single exponential rate law. The rate constant for RuBisCO folding, with either wild-type GroEL or SR1, is displayed. Error bars show the S.D. for n = 3–5 replicates. The SR1 reaction could not be reliably examined over the full temperature range, because of thermally induced disassembly of the SR1-GroES complex (based on gel filtration; data not show), which results in artificially low refolding rates.

The difference in persistence time of intracavity folding between the SR1 and cycling GroEL systems makes a specific prediction: if enhanced folding by GroEL is fundamentally limited only by the amount of time a non-native folding intermediate spends within the GroEL-GroES cavity, then the folding rate observed via SR1-mediated folding should represent the maximum rate achievable. If true, a cycling GroEL-GroES system should be slower than SR1 at low cycle rates and might approach, but could never exceed, the speed limit set by SR1 as the cycling rate increased. Because the GroEL-GroES cycling rate is ultimately limited by the rate of ATP hydrolysis, a simple way to control the cycling rate of the GroEL-GroES system is with temperature. As expected, when the temperature of a steady state cycling GroEL-GroES system is increased, the rate of ATP hydrolysis rises, whereas the lifetime of the GroEL-GroES cavity decreases (Fig. 6, b and c). When RuBisCO folding by SR1 is examined across this temperature range, the rate of intracavity folding is remarkably constant and insensitive to temperature, consistent with previous observations (Fig. 6d) (23). Folding by the cycling GroEL-GroES system, however, displays a strong dependence on temperature, as would be expected for a system constrained by the rate of productive cavity assembly and disassembly. Strikingly, whereas the rate of RuBisCO folding at low temperatures is slower than that of the SR1-GroES system, as the temperature reaches and exceeds 25 °C, the cycling GroEL-GroES system is capable of driving RuBisCO folding at rates that substantially exceed the rate achievable by SR1 (Fig. 6d).

It is worth noting that non-native substrate proteins also accelerate the GroEL-GroES reaction cycle, increasing the rate of ATP hydrolysis and decreasing the average cavity lifetime (15). To have a measurable impact, however, the non-native substrate protein must saturate the GroEL-GroES system. Because the conditions we employ are far below saturation, the presence of non-native RuBisCO would negligibly affect the ATPase rate or cavity lifetime of the cycling GroEL-GroES system in the experiments reported here. However, the concentration of non-native substrate protein in vivo is very likely to saturate the GroEL-GroES system under most conditions. In combination with the elevated temperatures typical for optimal growth by E. coli (35–37 °C), the GroEL-GroES system likely operates at a steady state rate within a living cell that results in a minimal cavity lifetime.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the trans ring of an ATP bullet complex can capture non-native RuBisCO during an active GroEL-GroES reaction cycle. Non-native RuBisCO can also bind directly to the trans ring of an ADP bullet (Fig. 2a) (21). However, the observation of direct capture of a folding intermediate by the ADP bullet trans ring is an artifact of the experimental conditions employed, in particular the subsaturating concentrations of the non-native substrate protein. The ADP bullet trans ring is expected to also possess high affinity for the substrate protein, because this complex is the next step in the GroEL reaction sequence (Fig. 1). More importantly, the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex is the first point in the reaction cycle where an open GroEL ring is exposed. The asymmetry of the GroEL cycle ensures this, because assembly of each new, ATP-bound cis cavity on a GroEL ring is directly linked to disassembly of the ADP-bound folding cavity on the other ring: the one left over from the previous round of folding (8, 15). In the presence of saturating substrate protein, conditions that would prevail in vivo, the first binding-capable state of the trans ring exposed, the ATP bullet trans ring, would then bind the incoming substrate protein. Our observations therefore suggest that the standard model of substrate protein entry into the GroEL reaction cycle requires revision (Fig. 1b).

Binding of substrate proteins to the ATP bullet trans ring explains how GroEL enforces a reliable ligand-binding sequence. Previous observations have shown that the release of non-native substrate protein and GroES from a spent cis folding cavity (the post-hydrolysis, ADP-bound complex; Fig. 1b) is fast, following ATP binding to the trans ring of the ADP bullet (11, 13, 15, 18). However, ADP release from the same decaying cis complex is slow (18, 19). In addition, it has been shown that the binding of non-native substrate proteins to an ADP-bound GroEL ring catalyzes ADP release (18, 19). In combination, these observations suggest a coherent picture of how a specific and ordered ligand-binding sequence is achieved on an open GroEL ring during a steady state cycle. The trans ring of the ATP bullet can bind non-native substrate, but not GroES or ATP (Fig. 1b). Because the trans ring nucleotide-binding sites tend to remain filled with ADP until the ring captures a non-native folding intermediate, premature ATP binding is inhibited (41). Additionally, ADP occupancy of the trans ring acts as a potent noncompetitive inhibitor of ATP hydrolysis on the other ring (29). Thus, ADP in the trans ring of an ATP bullet complex expands the lifetime of the complex to 20–30 s at 25 °C, maximizing the opportunity for non-native substrate protein capture on the trans ring. At the same time, even if the trans ring ADP is prematurely released, negative cooperativity of ATP binding between the GroEL rings serves as an additional inhibitor of premature ATP binding to the trans ring (27, 42, 43).

Non-native substrate protein capture on the trans ring of the ATP bullet serves as the trigger for cycle progression. Because substrate protein binding appears to be linked to ADP release, and ADP release from the trans ring initiates ATP turnover in the cis ring, substrate protein binding to the trans ring effectively signals correct loading of a GroEL ring that is ready to begin the next folding cycle. Once substrate protein is loaded, the trans ring ADP is released, and the cis ring ATP can be hydrolyzed to create a new ADP bullet with the newly captured non-native substrate on the trans ring (Fig. 1b). Subsequent binding of ATP to this occupied trans ring then initiates a new round of GroES binding and encapsulation. Notably, this model predicts that entry of non-native substrate protein into the GroEL reaction cycle should stimulate both GroES release and ATP hydrolysis. Both effects have been observed (15, 28, 44).

The ordered binding sequence of substrate protein, followed by ATP and then GroES binding, maximizes the probability of productive substrate protein encapsulation on a GroEL ring while minimizing nonproductive cis complex formation. Recently, an alternate model of substrate loading was proposed that postulated that ATP binding to a GroEL ring always occurs before non-native substrate protein (20). This model was formulated from the kinetics of non-native substrate and ATP binding to the trans ring of an ADP bullet complex. However, this model creates an apparent paradox, given the observation that ATP binding to a GroEL ring substantially weakens the binding affinity of the non-native protein for the ring (45, 46), an effect that should cause premature substrate protein escape prior to GroES binding. As demonstrated here, however, the ADP bullet is not the most likely acceptor state of the non-native substrate protein during a cycling GroEL-GroES reaction. Substrate loading on the trans ring of the ATP bullet complex resolves this apparent paradox. Other recent work suggests that saturating levels of non-native substrate protein may shift the GroEL cycle from a reaction sequence centered on the alternating asymmetric complexes of ADP and ATP bullets to one involving symmetric complexes (so-called footballs) (30, 47). Because our experiments were conducted at subsaturating levels of non-native substrate protein, the observations presented here do not address the role of symmetric complexes. However, our conclusion that non-native protein enters the GroEL reaction cycle on the trans ring of the ATP bullet is consistent with this dual-cycle model.

The ligand-binding sequence described here also has important implications for understanding how GroEL stimulates productive protein folding through unfolding. The entry of a substrate protein on the trans ring of the ATP bullet provides the widest possible time window for binding-induced unfolding to progress. At the same time, by ensuring that the substrate protein binds prior to ATP, the GroEL ring has a second chance to disrupt the structure of a misfolded, non-native protein through forced expansion. For RuBisCO, both binding-induced unfolding, as well as forced unfolding, appears to occur across multiple spatial axes of the non-native monomer. The observation that the cycling GroEL-GroES system can drive RuBisCO folding at rates that exceed the limiting intracavity rate strongly suggests that substrate protein unfolding by GroEL is directly coupled to enhanced protein folding. As shown in Fig. 6, the more rapidly the GroEL-GroES system cycles, the better it folds RuBisCO, even though the intracavity folding rate is little changed. In combination with our previous observations with SR1 (21), these results strongly suggest that the more frequently the non-native RuBisCO monomer is subjected to binding-induced and forced expansion, the more effective is the overall process of folding.

Despite our observations of enhanced folding of RuBisCO through unfolding, a fundamentally unresolved question is the extent to which unfolding is employed across the wide range of substrate proteins upon which GroEL works. Unfolding of substrate proteins by GroEL appears to be varied, with some proteins showing evidence for GroEL-mediated unfolding, whereas others display little or none (21, 48–55). It seems likely this variability stems from the wide range of substrate proteins upon which GroEL operates. Three to four classes of GroEL substrate proteins have been identified in E. coli, ranging in their folding dependence on GroEL from very little to indispensable (56, 57). Proteins for which unfolding is likely a significant mechanism are those that populate meta-stable, kinetically trapped, misfolded states with little spontaneous access to the native state. Previous studies have demonstrated that RuBisCO is an example of this highly stringent type of substrate protein (33, 58, 59). Proteins that do not form kinetically trapped and misfolded intermediates, but instead populate long-lived, on-pathway intermediate states that are simply aggregation prone, probably gain little if any benefit from structural disruption by GroEL. Substrate proteins of this type are likely to derive their greatest benefit from either the simple, passive prevention of aggregation provided by sequestration within the GroEL-GroES cavity or from a less well understood stimulation provided by spatial constriction of the folding intermediate within the GroEL-GroES chamber. The relative extent to which these different mechanisms are employed by GroEL as it interacts with and folds different substrate proteins remains to be established.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Chavela Carr for helpful discussions and editorial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM065421 (to H. S. R.). This work was also supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31370743 (to Z. L.) and Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation Grant LR12C05001 (to Z. L.).

- FCS

- fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

- RuBisCO

- ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hartl F. U., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M. (2011) Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen B., Retzlaff M., Roos T., Frydman J. (2011) Cellular strategies of protein quality control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a004374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horwich A. L., Fenton W. A. (2009) Chaperonin-mediated protein folding. Using a central cavity to kinetically assist polypeptide chain folding. Q. Rev. Biophys. 42, 83–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin Z., Rye H. (2006) GroEL-mediated protein folding. Making the impossible, possible. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 211–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jewett A. I., Shea J.-E. (2010) Reconciling theories of chaperonin accelerated folding with experimental evidence. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 67, 255–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braig K., Otwinowski Z., Hegde R., Boisvert D. C., Joachimiak A., Horwich A. L., Sigler P. B. (1994) The crystal structure of the bacterial chaperonin GroEL at 2.8 A. Nature 371, 578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fenton W. A., Kashi Y., Furtak K., Horwich A. L. (1994) Residues in chaperonin GroEL required for polypeptide binding and release. Nature 371, 614–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rye H. S., Burston S. G., Fenton W. A., Beechem J. M., Xu Z., Sigler P. B., Horwich A. L. (1997) Distinct actions of cis and trans ATP within the double ring of the chaperonin GroEL. Nature 388, 792–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weissman J. S., Rye H. S., Fenton W. A., Beechem J. M., Horwich A. L. (1996) Characterization of the active intermediate of a GroEL-GroES-mediated protein folding reaction. Cell 84, 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mayhew M., da Silva A. C., Martin J., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Hartl F. U. (1996) Protein folding in the central cavity of the GroEL-GroES chaperonin complex. Nature 379, 420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weissman J. S., Hohl C. M., Kovalenko O., Kashi Y., Chen S., Braig K., Saibil H. R., Fenton W. A., Horwich A. L. (1995) Mechanism of GroEL action. Productive release of polypeptide from a sequestered position under GroES. Cell 83, 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Todd M. J., Viitanen P. V., Lorimer G. H. (1994) Dynamics of the chaperonin ATPase cycle. Implications for facilitated protein folding. Science 265, 659–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weissman J. S., Kashi Y., Fenton W. A., Horwich A. L. (1994) GroEL-mediated protein folding proceeds by multiple rounds of binding and release of nonnative forms. Cell 78, 693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ranson N. A., Dunster N. J., Burston S. G., Clarke A. R. (1995) Chaperonins can catalyse the reversal of early aggregation steps when a protein misfolds. J. Mol. Biol. 250, 581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rye H. S., Roseman A. M., Chen S., Furtak K., Fenton W. A., Saibil H. R., Horwich A. L. (1999) GroEL-GroES cycling. ATP and nonnative polypeptide direct alternation of folding-active rings. Cell 97, 325–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lorimer G. (1997) Protein folding. Folding with a two-stroke motor. Nature 388, 720–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koike-Takeshita A., Yoshida M., Taguchi H. (2008) Revisiting the GroEL-GroES reaction cycle via the symmetric intermediate implied by novel aspects of the GroEL(D398A) mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23774–23781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Madan D., Lin Z., Rye H. S. (2008) Triggering protein folding within the GroEL-GroES complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32003–32013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grason J. P., Gresham J. S., Widjaja L., Wehri S. C., Lorimer G. H. (2008) Setting the chaperonin timer. A two-stroke, two-speed, protein machine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17334–17338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tyagi N. K., Fenton W. A., Horwich A. L. (2009) GroEL/GroES cycling. ATP binds to an open ring before substrate protein favoring protein binding and production of the native state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20264–20269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin Z., Madan D., Rye H. S. (2008) GroEL stimulates protein folding through forced unfolding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 303–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin Z., Rye H. S. (2004) Expansion and compression of a protein folding intermediate by GroEL. Mol. Cell 16, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brinker A., Pfeifer G., Kerner M. J., Naylor D. J., Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2001) Dual function of protein confinement in chaperonin-assisted protein folding. Cell 107, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang Y. C., Chang H. C., Roeben A., Wischnewski D., Wischnewski N., Kerner M. J., Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2006) Structural features of the GroEL-GroES nano-cage required for rapid folding of encapsulated protein. Cell 125, 903–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rye H. (2001) Application of fluorescence resonance energy transfer to the GroEL-GroES chaperonin reaction. Methods 24, 278–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Puchalla J., Krantz K., Austin R., Rye H. (2008) Burst analysis spectroscopy. A versatile single-particle approach for studying distributions of protein aggregates and fluorescent assemblies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14400–14405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burston S. G., Ranson N. A., Clarke A. R. (1995) The origins and consequences of asymmetry in the chaperonin reaction cycle. J. Mol. Biol. 249, 138–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grason J. P., Gresham J. S., Widjaja L., Wehri S. C., Lorimer G. H., (2008) Setting the chaperonin timer. The effects of K+ and substrate protein on ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17334–17338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kad N. M., Ranson N. A., Cliff M. J., Clarke A. R. (1998) Asymmetry, commitment and inhibition in the GroE ATPase cycle impose alternating functions on the two GroEL rings. J. Mol. Biol. 278, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sameshima T., Iizuka R., Ueno T., Wada J., Aoki M., Shimamoto N., Ohdomari I., Tanii T., Funatsu T. (2010) Single-molecule study on the decay process of the football-shaped GroEL-GroES complex using zero-mode waveguides. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23159–23164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sparrer H., Buchner J. (1997) How GroES regulates binding of nonnative protein to GroEL. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 14080–14086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saibil H. R., Zheng D., Roseman A. M., Hunter A. S., Watson G. M., Chen S., Auf Der Mauer A., O'Hara B. P., Wood S. P., Mann N. H., Barnett L. K., Ellis R. J. (1993) ATP induces large quaternary rearrangements in a cage-like chaperonin structure. Curr. Biol. 3, 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goloubinoff P., Christeller J. T., Gatenby A. A., Lorimer G. H. (1989) Reconstitution of active dimeric ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase from an unfolded state depends on two chaperonin proteins and Mg-ATP. Nature 342, 884–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van der Vies S. M., Viitanen P. V., Gatenby A. A., Lorimer G. H., Jaenicke R. (1992) Conformational states of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase and their interaction with chaperonin 60. Biochemistry 31, 3635–3644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Todd M. J., Lorimer G. H., Thirumalai D. (1996) Chaperonin-facilitated protein folding. Optimization of rate and yield by an iterative annealing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4030–4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Csermely P. (1999) Chaperone-percolator model. A possible molecular mechanism of Anfinsen-cage-type chaperones. Bioessays 21, 959–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Edwards R. A., Huber R. E. (1992) Surface denaturation of proteins. The thermal inactivation of β-galactosidase (Escherichia coli) on wall-liquid surfaces. Biochem. Cell Biol. 70, 63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Graham D. E., Phillips M. C. (1979) Proteins at liquid interfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 70, 403–414 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bull H. B., Neurath H. (1937) The denaturation and hydration of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 118, 163–175 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sen P., Yamaguchi S., Tahara T. (2008) New insight into the surface denaturation of proteins. Electronic sum frequency generation study of cytochrome c at water interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 13473–13475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sameshima T., Ueno T., Iizuka R., Ishii N., Terada N., Okabe K., Funatsu T. (2008) Football- and bullet-shaped GroEL-GroES complexes coexist during the reaction cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23765–23773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yifrach O., Horovitz A. (1995) Nested cooperativity in the ATPase activity of the oligomeric chaperonin GroEL. Biochemistry 34, 5303–5308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yifrach O., Horovitz A. (1994) Two lines of allosteric communication in the oligomeric chaperonin GroEL are revealed by the single mutation Arg196→Ala. J. Mol. Biol. 243, 397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Staniforth R. A., Burston S. G., Atkinson T., Clarke A. R. (1994) Affinity of chaperonin-60 for a protein substrate and its modulation by nucleotides and chaperonin-10. Biochem. J. 300, 651–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Badcoe I. G., Smith C. J., Wood S., Halsall D. J., Holbrook J. J., Lund P., Clarke A. R. (1991) Binding of a chaperonin to the folding intermediates of lactate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 30, 9195–9200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Martin J., Langer T., Boteva R., Schramel A., Horwich A. L., Hartl F. U. (1991) Chaperonin-mediated protein folding at the surface of groEL through a “molten globule-” like intermediate. Nature 352, 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sameshima T., Iizuka R., Ueno T., Funatsu T. (2010) Denatured proteins facilitate the formation of the football-shaped GroEL-(GroES)2 complex. Biochem. J. 427, 247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Horst R., Fenton W. A., Englander S. W., Wüthrich K., Horwich A. L. (2007) Folding trajectories of human dihydrofolate reductase inside the GroEL GroES chaperonin cavity and free in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20788–20792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sharma S., Chakraborty K., Müller B. K., Astola N., Tang Y.-C., Lamb D. C., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U. (2008) Monitoring protein conformation along the pathway of chaperonin-assisted folding. Cell 133, 142–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zahn R., Perrett S., Stenberg G., Fersht A. (1996) Catalysis of amide proton exchange by the molecular chaperones GroEL and SecB. Science 271, 642–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen J., Walter S., Horwich A. L., Smith D. L. (2001) Folding of malate dehydrogenase inside the GroEL-GroES cavity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim S. Y., Miller E. J., Frydman J., Moerner W. E. (2010) Action of the chaperonin GroEL/ES on a non-native substrate observed with single-molecule FRET. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hofmann H., Hillger F., Pfeil S. H., Hoffmann A., Streich D., Haenni D., Nettels D., Lipman E. A., Schuler B. (2010) Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein folding in a chaperonin cage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11793–11798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hammarstrom P. (2001) Protein compactness measured by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Human carbonic anhydrase II is considerably expanded by the interaction of GroEL. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21765–21775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hammarström P., Persson M., Owenius R., Lindgren M., Carlsson U. (2000) Protein substrate binding induces conformational changes in the chaperonin GroEL. A suggested mechanism for unfoldase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22832–22838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kerner M. J., Naylor D. J., Ishihama Y., Maier T., Chang H. C., Stines A. P., Georgopoulos C., Frishman D., Hayer-Hartl M., Mann M., Hartl F. U. (2005) Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell 122, 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fujiwara K., Ishihama Y., Nakahigashi K., Soga T., Taguchi H. (2010) A systematic survey of in vivo obligate chaperonin-dependent substrates. EMBO J. 29, 1552–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goloubinoff P., Gatenby A. A., Lorimer G. H. (1989) GroE heat-shock proteins promote assembly of foreign prokaryotic ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase oligomers in Escherichia coli. Nature 337, 44–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schmidt M., Buchner J., Todd M. J., Lorimer G. H., Viitanen P. V. (1994) On the role of groES in the chaperonin-assisted folding reaction. Three case studies. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 10304–10311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]