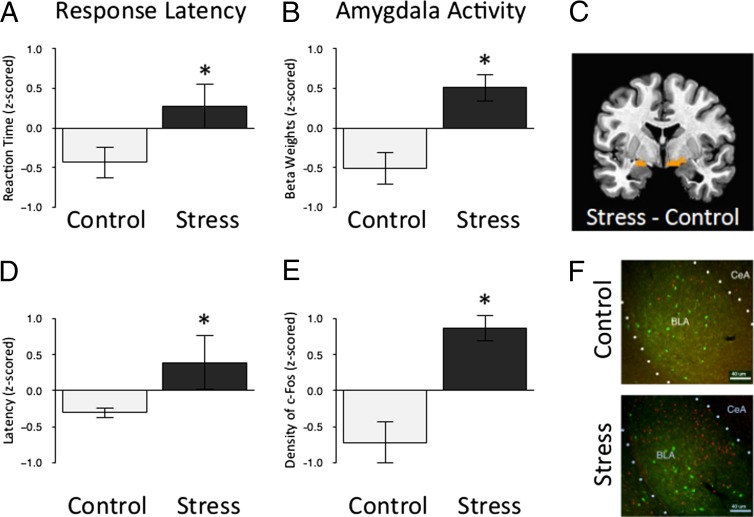

Fig. 3.

Greater amygdala activity in humans and mice following ELS. (A) Stressed preadolescent humans take longer than their standard reared counterparts to detect frequently presented neutral targets embedded among rare threat nontarget cues that they were instructed to ignore (t = 2.08; P < 0.05; nc = 10; nels = 16). Data are z-scored and expressed as means ± SEM. (B) Parameter estimates of amygdala activity in response to the threat cue (i.e., fearful face) were greater in stressed preadolescent humans than their standard-reared counterparts (F = 4.43; P < 0.05; nc = 10; nels = 16). (C) Bilateral region of the amygdala identified as more reactive to threat (i.e., fear face stimuli) in stressed preadolescent humans than their standard reared counterparts. (D) The difference in time that control and stressed preadolescent mice take to approach a cue in a novel cage compared with their home cage (F = 2.06; P < 0.05; nc = 18; nels = 14). Data are z-scored and expressed as means ± SEM. (E) The density of c-Fos protein in the amygdala following exposure to the threatening context (i.e., novel cage) was greater in stressed preadolescent mice than their standard-reared counterparts [t = 4.71; P < 0.001; nc = 6; nels = 5 (10–15 slices per animal)]. Data are z-scored and expressed as means ± SEM. (F) An individual slice cut through the amygdala taken from each mouse was stained for c-Fos (red) and PVA (green) and used for quantification of c-Fos following exposure to the threatening context, clustered by experimental group and at 10x magnification.