Abstract

Purpose

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib undergoes oxidative hepatic metabolism. This study (NCI-6432; NCT00091117) was conducted to evaluate bortezomib pharmacokinetics and safety in patients with varying degrees of hepatic impairment, to inform dosing recommendations in these special populations.

Methods

Patients received bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of 21-day cycles. Patients were assigned to four hepatic function groups based on the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group classification. Those with normal function received bortezomib at the 1.3 mg/m2 standard dose. Patients with severe, moderate, and mild impairment received escalating doses from 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0 mg/m2, respectively, up to a 1.3 mg/m2 maximum. Serial blood samples were collected for 24 hours post-dose on days 1 and 8, cycle 1, for bortezomib plasma concentration measurements.

Results

Sixty-one patients were treated, including 14 with normal hepatic function and 17, 12, and 18 with mild, moderate, and severe impairment, respectively. Mild hepatic impairment did not alter dose-normalized bortezomib exposure (AUC0-tlast) or Cmax compared with patients with normal function. Mean dose-normalized AUC0-tlast was increased by approximately 60% on day 8 in patients with moderate or severe impairment.

Conclusions

Patients with mild hepatic impairment do not require a starting dose adjustment of bortezomib. Patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment should be started at a reduced dose of 0.7 mg/m2.

Keywords: Bortezomib, hepatic impairment, pharmacokinetics, cytochrome P450 enzymes, metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Bortezomib (VELCADE®) is an inhibitor of the 20S proteasome, a multi-catalytic complex of the ubiquitin–proteasome system that is responsible for the degradation of the majority of intracellular proteins (1,2). Proteasome inhibition disrupts multiple cellular signaling pathways, leading to the inhibition of cell-cycle progression, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of angiogenesis and proliferation, and results in anti-tumor activity in a number of tumor types (1-3). Bortezomib is approved for the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma in the United States (US) (4), European Union (5), and other countries worldwide, and also in the US for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least one prior therapy (4).

Bortezomib is oxidatively metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes to pharmacologically inactive deboronated metabolites (6-8). The primary CYP enzymes involved, as determined by in vitro human liver microsomal metabolism studies, are 3A4, 2C19, and 1A2, with 2D6 and 2C9 playing a minor role (4,6-8). Clinical drug-drug interaction studies in cancer patients have shown that bortezomib exposure is increased by approximately 35% upon co-administration with the strong CYP3A inhibitor ketoconazole (9), but is unaffected by co-administration of omeprazole, a potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 (10). The results of the drug-drug interaction study with ketoconazole support the conclusion of a partial contribution of CYP3A-mediated oxidative metabolism to the hepatic clearance of bortezomib, consistent with the results of in vitro metabolic phenotyping studies (8). Based on the results of a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Organ Dysfunction Working Group (ODWG) study, the pharmacokinetics of bortezomib are not altered by varying grades of renal impairment (including patients on dialysis who were administered bortezomib after the dialysis procedure), supporting the lack of a need for dosage adjustments in patients with renal impairment (11). These results are consistent with hepatic metabolism rather than renal clearance being the primary route of clearance of bortezomib.

Thus, as bortezomib undergoes oxidative hepatic metabolism, its pharmacokinetics may be altered in patients with hepatic impairment, making it important to evaluate safety and pharmacokinetics in this population. The recommended dose and schedule of bortezomib is 1.3 mg/m2, delivered by intravenous administration on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of 21-day cycles. Pharmacokinetic studies of bortezomib have been performed at this recommended dose and schedule in patients with multiple myeloma (12). However, they have not, to date, been specifically undertaken in patients with hepatic impairment. Studies of anti-cancer agents in this population are important for characterizing the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of these agents in the setting of hepatic impairment, with the aim of developing scientifically informed dosing guidelines for their appropriate use in patients with liver dysfunction.

This phase 1 study was undertaken by the NCI ODWG, under a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., to evaluate the pharmacokinetics and safety of bortezomib in patients with varying degrees of hepatic impairment and to inform dosing recommendations in these subpopulations. The findings of this study have resulted in an update to the United States Prescribing Information, which now includes guidelines on appropriate dosing in patients with varying grades of hepatic impairment (4).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients

Patients aged ≥18 years with histologically confirmed malignancy for which no standard curative or life-extending therapy exists were eligible. Tumor types could include solid tumors, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma (as evidenced by liver mass, elevated alfa-fetoprotein ≥500 ng/mL, and positive serology for hepatitis). No symptomatic CNS metastases were allowed; brain metastases were permitted in patients who had received prior definitive treatment, had stable disease for ≥4 weeks, and were not currently on enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants and steroids. Other eligibility criteria included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2; life expectancy of ≥12 weeks; absolute neutrophil count ≥1000/mm3 and platelet count ≥100,000/mm3; serum creatinine ≤1.5 mg/dL; and in patients with biliary obstruction for which a stent had been placed, the stent had to have been in place for ≥10 days and the patient was required to have stable liver function (same hepatic function group at two measurements taken ≥2 days apart).

Patients were excluded if they had symptomatic congestive heart failure, unstable angina pectoris, cardiac arrhythmia, or New York Heart Association class III or IV heart disease. Other exclusion criteria included: pre-existing neuropathy of grade ≥2 severity according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 3.0; prior immunotherapy or biologic therapy within 4 weeks, chemotherapy within 3 weeks, nitrosoureas or mitomycin within 6 weeks, radiotherapy within 2 weeks, or surgery within 3 weeks of enrollment; prior radiotherapy to >50% of the bone marrow; or prior use of bortezomib.

Study design

The objectives of this study were to determine the safety, tolerability, and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of bortezomib in patients with varying degrees of liver dysfunction, and to determine the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bortezomib in patients with mild, moderate, or severe hepatic impairment. The aim of these analyses was to inform dosing recommendations for bortezomib in these subpopulations of patients with hepatic dysfunction. This phase 1 multicenter study enrolled patients at 9 sites in the US between September 2004 and January 2010. Patients were assigned to four groups based on hepatic function, defined according to bilirubin and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels relative to the upper limit of normal (ULN) using the classification developed for organ dysfunction studies by the NCI ODWG (13-15). Normal function was defined as bilirubin and AST ≤ULN. Patients with mild hepatic impairment had bilirubin ≤ULN and AST >ULN, or bilirubin >1.0–1.5 x ULN (with any AST). Moderate and severe hepatic impairment were defined as bilirubin >1.5–3 x ULN and >3 x ULN, respectively, with any AST. No distinction was made between liver dysfunction due to metastases or due to other causes. Patients assigned to one group at screening who had a change in liver function prior to being treated were switched to the appropriate group.

Patients received bortezomib on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of 21-day cycles. Patients with normal hepatic function received bortezomib at the standard dose of 1.3 mg/m2 as an intravenous bolus. Dose escalation in patients with severe, moderate, and mild hepatic impairment proceeded from starting doses of 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0 mg/m2, respectively, via a standard 3+3 design, up to a maximum of 1.3 mg/m2. No intra-patient dose escalation was permitted. The MTD was to be defined within each hepatic function group as the dose preceding that at which ≥2 of 3–6 patients experienced dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). DLT was defined as the following AEs occurring in cycle 1 and considered probably or definitely related to bortezomib: grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia lasting at least 7 days, or neutropenic fever with grade 3 or 4 neutropenia; grade ≥3 non-hematologic toxicity; or specific liver toxicity. This comprised, in the mild impairment group, an increase in total bilirubin level with crossing to the severe group lasting >2 weeks; in the moderate impairment group, a 1.5-fold increase from baseline in total bilirubin level with crossing to the severe group, lasting >2 weeks; and in the severe impairment group, a 1.5-fold increase from baseline in total bilirubin level lasting >2 weeks. The definition of DLT also included significant toxicity in the first cycle requiring dose reduction.

Patients were not permitted to receive concurrent immunotherapy, thalidomide, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, other investigational agents, or antiretroviral therapy (in HIV-positive patients). Concurrent epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa for management of cancer-associated anemia was permitted, as were concurrent CYP-interacting agents providing that they were used with caution, and concurrent bisphosphonate therapy was permitted except during cycle 1. Bortezomib treatment was continued until the occurrence of disease progression, intercurrent illness preventing further treatment administration, unacceptable adverse events (AEs), failure to recover from toxicity within 2 weeks, or patient or investigator decision to discontinue treatment.

Review boards at all participating institutions approved the study, which was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent. This study is registered with www.ClinicalTrials.gov, with the identifier NCT00091117.

Assessments

AEs were graded according to NCI CTCAE, version 3.0 and recorded throughout the study and until 30 days after the last dose of bortezomib. Serial blood samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were collected before drug administration and for 24 hours post-dose on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1 for measurement of bortezomib plasma concentrations. Samples were collected at the following time points post-dose: 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes, and 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours. Plasma concentrations of bortezomib were measured using validated liquid–liquid extraction and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) assays at either Tandem Labs, West Trenton, NJ (assay range 0.1–25 ng/mL) or at Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (assay range 0.1–20 ng/mL) (9). Plasma samples with concentrations above the upper limit of quantification were adequately diluted into the assay range. Plasma concentrations below the lower limit of quantification were set to 0 ng/mL for pharmacokinetic calculations.

Individual plasma concentration–time data were utilized for non-compartmental analysis using WinNonlin Professional Version 5.2 (Pharsight Corporation). Maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) was observed directly for each patient on days 1 and 8. The area under the concentration–time curve from time zero to the point of last quantifiable concentration (AUC0-tlast) on days 1 and 8 was estimated by log-linear trapezoidal approximation. Dose-normalized individual Cmax and AUC0-tlast values were calculated.

Whole blood samples for determination of the pharmacodynamic effect of bortezomib were collected on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1 prior to dosing and at 1, 6, and 24 hours after dosing. Pharmacodynamic assays were performed at Millennium and blood 20S proteasome activity was expressed as the ratio of chymotryptic to tryptic activity (16). Patients with measurable disease were assessed for response according to standard criteria – the Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.0) (17) for patients with solid tumors, and the International Working Group criteria (18) for patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Statistical analysis

The safety profile was evaluated in all treated patients overall and by hepatic function group. No formal statistical comparisons of rates of AEs between hepatic function groups or individual dose cohorts within hepatic function groups were conducted due to the small sample sizes and because dose-normalization of AEs is not possible. Pharmacokinetics were evaluated in the pharmacokinetic-evaluable population. This was defined as patients with sufficient dosing information and plasma concentration versus time data over 0–24 hours post-dose to permit calculation of AUC0-tlast using non-compartmental methods. Additionally, to be pharmacokinetic-evaluable on day 8, patients should have received the protocol-specified dose of bortezomib on days 1, 4, and 8 without dose adjustments or interruptions. A minimum of 12 patients were to be treated in each hepatic function group in order to have adequate data on pharmacokinetic parameters. Dose-normalized Cmax and AUC0-tlast were log-transformed and subjected to an analysis of variance. A linear mixed-effects model included fixed effects for day, group, and the day–group interaction. A compound symmetry structure was used to model the covariance (within subject variability). The ratios of geometric least square means and 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for dose-normalized Cmax and AUC0-tlast in each hepatic impairment group in reference to the normal hepatic function group were calculated.

RESULTS

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 63 patients were enrolled to the study. One patient with moderate hepatic impairment was not treated due to complications after the placement of a biliary stent prior to the initiation of treatment. One patient with severe hepatic impairment received a single dose of bortezomib 0.7 mg/m2 before withdrawing due to deteriorating clinical status; no post-baseline information was recorded, and this patient was thus excluded from the safety population for analysis. Among the 61 patients in the safety population, 14 had normal hepatic function, and 17, 12, and 18 had mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, respectively. Patient disposition and baseline characteristics, overall and by hepatic function group, are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 51% of patients were male, the median age was 62 years (range 30–85 years), and 11%, 59%, and 30% of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The most common malignancy was colorectal cancer, which was seen in 39% of patients.

Table 1.

Definition of hepatic function groups, and patient disposition and baseline characteristics overall and by hepatic function group.

| All, N=61 | Hepatic function/impairment group

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal, N=14 | Mild, N=17 | Moderate, N=12 | Severe, N=18 | |||

| Hepatic function group definition | ||||||

| Bilirubin level | – | ≤ULN | ≤ULN | >1.0–1.5 x ULN | >1.5–3 x ULN | >3 x ULN |

| AST level | – | ≤ULN | AST > ULN | Any AST | Any AST | Any AST |

|

| ||||||

| Bortezomib dose group, n (%) | ||||||

| 0.5 mg/m2 | 5 (8) | – | – | – | 5 (28) | |

| 0.7 mg/m2 | 15 (25) | – | – | 9 (75) | 6 (33) | |

| 1.0 mg/m2 | 16(26) | – | 6 (35) | 3 (25) | 7 (39) | |

| 1.3 mg/m2 | 25 (41) | 14 (100) | 11 (65) | – | – | |

| Evaluable for pharmacokinetics, n (%) | 60 (98) | 13 (93) | 17 (100) | 12 (100) | 18 (100) | |

|

| ||||||

| Median age, years (range) | 62 (30–85) | 64 (47–79) | 64 (35–85) | 61.5 (30–75) | 59.5 (35–74) | |

| Male, n (%) | 31 (51) | 8 (57) | 7 (41) | 6 (50) | 10 (56) | |

| White, n (%) | 57 (93) | 14 (100) | 15 (88) | 12 (100) | 16 (89) | |

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||||||

| Colorectal | 24 (39) | 1 (7) | 7 (41) | 5 (42) | 11 (61) | |

| Liver | 7 (11) | 1 (7) | 3 (18) | 2 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| NSCLC and other lung | 6 (10) | 3 (21) | 2 (12) | – | 1 (6) | |

| Breast | 5 (8) | 1 (7) | 1 (6) | 2 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| Pancreas | 4 (7) | – | 1 (6) | 2 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 3 (5) | 3 (21) | – | – | – | |

| Other* | 12 (20) | 5 (36) | 3 (18) | 1 (8) | 3 (17) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 7 (11) | 2 (14) | 2 (12) | 1 (8) | 2 (11) | |

| 1 | 36 (59) | 11 (79) | 9 (53) | 7 (58) | 9 (50) | |

| 2 | 18 (30) | 1 (7) | 6 (35) | 4 (33) | 7 (39) | |

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PS, performance status; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Including 1 cholangiocarcinoma (severe group), 2 gallbladder (both mild group), 2 head and neck (1 normal, 1 severe group), 2 melanoma (1 normal, 1 mild group), 1 other gastrointestinal (normal group), 1 ovarian (normal group), 1 prostate (normal group), and 2 sarcoma (1 moderate, 1 severe group).

Dose escalation and treatment exposure

Dose escalation proceeded to 1.3 mg/m2 in patients with mild hepatic impairment and to 1.0 mg/m2 in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Three patients were reported to have experienced significant toxicity – grade 2 vomiting probably related to treatment in a patient in the normal hepatic function group; grade 3 convulsion possibly related to treatment in a patient in the mild hepatic impairment group treated at 1.3 mg/m2; and grade 2 bilirubin increase in a patient in the moderate hepatic impairment group that evolved to grade 3. However, none of these events met the protocol-defined criteria for DLT. Dose escalation did not proceed to 1.3 mg/m2 in the moderate and severe hepatic impairment groups based upon an interim review of available safety and pharmacokinetic data that indicated an approximately 60% higher bortezomib dose-normalized AUC in patients with moderate and severe hepatic impairment compared to patients with normal hepatic function. It was therefore inferred that dose escalation beyond 1.0 mg/m2 in these hepatic impairment groups could be expected to result in exposures exceeding maximally tolerated exposures in patients with normal hepatic function.

Patients received a median of 1 cycle of treatment (range 1–7) overall, including medians (ranges) of 2 (1–7), 1 (1–4), 1 (1–3), and 1 (1–3) in patients with normal hepatic function and mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, respectively. Only 26 (43%) patients received ≥2 cycles, including 5 (9%) who received ≥3 cycles. The main reason for study discontinuation was disease progression in 37 (61%) patients, including 8 (57%), 11 (65%), 9 (75%), and 9 (50%) patients in the normal function and mild, moderate, and severe impairment groups, respectively. In addition, 7 (11%) patients refused further participation, 4 (7%) discontinued due to AEs, as described below, 4 (7%) had complicating disease, 2 (3%) died during treatment, and 7 (11%) discontinued for other reasons.

Safety

The safety profile of bortezomib and the most common AEs (all grades, and grade ≥3) are summarized in Table 2 by hepatic function group and dose level. Rates of grade ≥3 AEs were 71% in patients with normal hepatic function and 83%, 82%, 78%, 100%, 80%, 83%, and 86% in patients with mild (1.0 and 1.3 mg/m2), moderate (0.7 and 1.0 mg/m2), or severe (0.5, 0.7, and 1.0 mg/m2) impairment, respectively; respective rates of grade ≥4 AEs were 14% and 17%, 45%, 33%, 33%, 40%, 67%, and 57%, and of serious AEs were 29% and 50%, 55%, 56%, 33%, 60%, 67%, 29%. These rates thus appeared numerically somewhat higher in patients with hepatic impairment than in the normal hepatic function group. Similarly, the incidence of commonly reported AEs associated with hepatic function appeared numerically higher in patients with hepatic impairment versus those with normal function. Elevated AST was seen in 7% of patients with normal hepatic function and in 33%, 18%, 33%, 33%, 40%, 17%, and 29% in patients with mild (1.0 and 1.3 mg/m2), moderate (0.7 and 1.0 mg/m2), or severe (0.5, 0.7, and 1.0 mg/m2) impairment, respectively. Respective rates of elevated blood bilirubin were 7% compared with 33%, 18%, 22%, 100%, 20%, 0%, and 43%. Elevations in liver function test parameters were not considered to be drug-related.

Table 2.

Safety profile of bortezomib overall and by hepatic function group and dose level, including most common AEs of any grade (reported in ≥30% of patients) and of grade ≥3 severity (reported in ≥10% of patients).

| AE, n (%) | All, N=61 | Hepatic function/impairment group

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal, N=14 | Mild, N=17 | Moderate, N=12 | Severe, N=18 | ||||||

| 1.0 (n=6) |

1.3 (n=11) |

0.7 (n=9) |

1.0 (n=3) |

0.5 (n=5) |

0.7 (n=6) |

1.0 (n=7) |

|||

| Any AE | 59 (97) | 14 (100) | 6 (100) | 10 (91) | 9 (100) | 3 (100) | 5 (100) | 5 (83) | 7 (100) |

| Fatigue | 31 (51) | 7 (50) | 1 (17) | 7 (64) | 4 (44) | 2 (67) | 4 (80) | 3 (50) | 3 (43) |

| Nausea | 24 (39) | 8 (57) | 1 (17) | 6 (55) | 2 (22) | 2 (67) | 1 (20) | 2 (33) | 2 (29) |

| Anorexia | 19 (31) | 5 (36) | 2 (33) | 3 (27) | 4 (44) | 2 (67) | 0 | 0 | 3 (43) |

| Dyspnea | 19 (31) | 5 (36) | 2 (33) | 4 (36) | 2 (22) | 1 (33) | 1 (20) | 1 (17) | 3 (43) |

| Decreased platelet count | 18 (30) | 6 (43) | 0 | 4 (36) | 3 (33) | 2 (67) | 0 | 1 (17) | 2 (29) |

| Any grade ≥3 AE | 49 (80) | 10 (71) | 5 (83) | 9 (82) | 7 (78) | 3 (100) | 4 (80) | 5 (83) | 6 (86) |

| Fatigue | 9 (15) | 2 (14) | 0 | 2 (18) | 0 | 0 | 2 (40) | 2 (33) | 1 (14) |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 7 (11) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9) | 1 (11) | 3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 (29) |

| Decreased platelet count | 7 (11) | 2 (14) | 0 | 2 (18) | 2 (22) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 |

| Increased AST | 6 (10) | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 3 (33) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (14) |

| Any grade ≥4 AE | 22 (36) | 2 (14) | 1 (17) | 5 (45) | 3 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (40) | 4 (67) | 4 (57) |

| Any drug-related AE | 40 (66) | 13 (93) | 4 (67) | 10 (91) | 4 (44) | 3 (100) | 2 (40) | 2 (33) | 2 (29) |

| Any serious AE | 28 (46) | 4 (29) | 3 (50) | 6 (55) | 5 (56) | 1 (33) | 3 (60) | 4 (67) | 2 (29) |

| Discontinuation due to AE | 4 (7) | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (9) | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) |

| On-study deaths | 15 (25) | 2 (14) | 0 | 4 (36) | 2 (22) | 0 | 2 (40) | 3 (50) | 2 (29) |

Increasing degrees of hepatic impairment did not appear to increase toxicity at the dose levels studied. In the moderate (0.7 mg/m2) and severe (0.7 and 1.0 mg/m2) hepatic impairment cohorts, the incidences of AEs (all grades), grade ≥3 AEs, and discontinuations due to AEs were consistent with the safety profile of the normal hepatic function cohort (1.3 mg/m2). Within each hepatic impairment cohort, there was no apparent dose relationship with the frequency of serious AEs. For the most commonly reported AEs, there were no apparent trends indicating increased overall frequency with increasing degree of hepatic impairment or with increasing dose within each hepatic impairment group.

Four patients discontinued bortezomib due to AEs of grade 4 elevated blood bilirubin in 2 patients, grade 3 hypotension in 1 patient, and a combination of grade 2 decreased platelet count and grade 2 leukopenia in 1 patient. There were 15 deaths during the study; 12 were due to disease progression, and cause of death was recorded as hepatic failure, pneumonia, and sudden death in the remaining three patients.

Pharmacokinetics

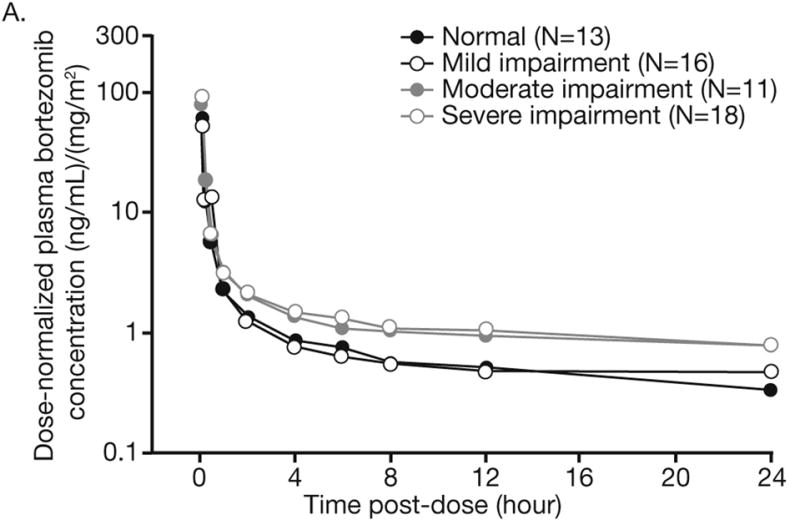

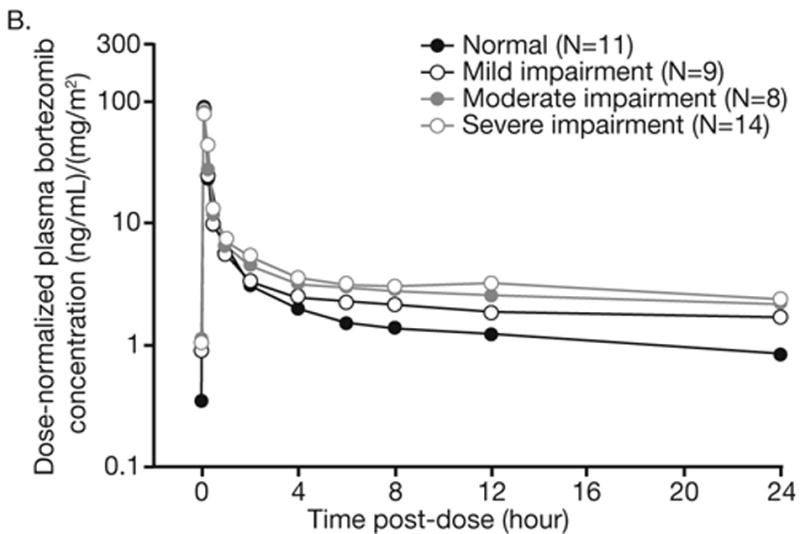

Pharmacokinetic samples and data were available for 60 patients across the hepatic function groups, including 13, 17, 12, and 18 patients with normal hepatic function, and mild, moderate, and severe impairment, respectively. Bortezomib displayed multi-exponential disposition kinetics on days 1 and 8 across the hepatic function groups, with a rapid initial distribution phase followed by a slower decline in plasma concentrations in the terminal phase, based on inspection of mean dose-normalized plasma concentration-time profiles (Figure 1). Across the hepatic function groups, geometric mean dose-normalized AUC0-tlast was greater on day 8 than on day 1 (Table 3). Distribution of dose-normalized bortezomib exposure was comparable in patients with normal hepatic function and mild hepatic impairment, but was higher in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Figure 2). There were no readily apparent consistent effects of hepatic impairment on dose-normalized Cmax of bortezomib (Table 3, Figure 2). Consistently, the results of statistical analysis of pharmacokinetic parameters (Table 4) indicated that mild hepatic impairment did not alter either dose-normalized AUC0-tlast or Cmax although mean dose-normalized AUC0-tlast was increased by approximately 60% on Day 8 in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment.

Figure 1.

Mean dose-normalized plasma concentration–time profiles of bortezomib on days (A) 1 and (B) 8 of cycle 1 by hepatic function group.

Table 3.

Geometric mean (%CV) dose-normalized AUC0-tlast and dose-normalized Cmax on days 1 and 8 in patients by hepatic function.

| Day | Hepatic function group | N | Dose-normalized AUC0-tlast (ng.hr/mL)/(mg/m2) | Dose-normalized Cmax (ng/mL)/(mg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | 13 | 30.2 (27) | 56.7 (43) |

| Mild impairment | 16 | 26.3 (69) | 43.4 (78) | |

| Moderate impairment | 11 | 43.6 (45) | 62.1 (59) | |

| Severe impairment | 18 | 47.8 (37) | 81.8 (54) | |

|

| ||||

| 8 | Normal | 11 | 52.2 (26) | 88.9 (29) |

| Mild impairment | 9 | 51.9 (91) | 79.6 (50) | |

| Moderate impairment | 8 | 85.0 (27) | 73.7 (62) | |

| Severe impairment | 14 | 83.2 (57) | 91.4 (58) | |

Figure 2.

Individual (filled circles) and geometric mean (open squares) values of dose-normalized AUC0-tlast on day 1 (A) and day 8 (B), and dose-normalized Cmax on day 1 (C) and day 8 (D), by hepatic function group.

Table 4.

Geometric least square mean ratios for dose-normalized AUC0-tlast and dose-normalized Cmax between hepatic impairment groups.

| Comparison vs normal | Geometric least square mean ratio (90% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 8 | |

| Dose-normalized AUC0-tlast | ||

| Mild hepatic impairment | 0.902 (0.662-1.228) | 0.952 (0.671-1.352) |

| Moderate hepatic impairment | 1.468 (1.047-2.057) | 1.638 (1.134-2.365) |

| Severe hepatic impairment | 1.581 (1.168-2.140) | 1.524 (1.103-2.105) |

| Average of moderate/severe hepatic impairment | 1.523 (1.152-2.014) | 1.580 (1.172-2.131) |

| Dose-normalized Cmax | ||

| Mild hepatic impairment | 0.779 (0.510-1.188) | 0.863 (0.527-1.412) |

| Moderate hepatic impairment | 1.143 (0.720-1.815) | 0.782 (0.468-1.306) |

| Severe hepatic impairment | 1.441 (0.953-2.177) | 0.962 (0.614-1.505) |

| Average of moderate/severe hepatic impairment | 1.283 (0.876-1.879) | 0.867 (0.572-1.314) |

Of the 60 pharmacokinetic-evaluable patients that contributed to this analysis, a total of four patients (two with mild and one each with moderate and severe hepatic impairment) were receiving concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers. Specifically, these included a patient with mild hepatic impairment receiving the CYP3A inducer oxcarbazepine, another patient with mild hepatic impairment receiving the CYP3A inducer phenytoin and the moderate CYP3A inhibitor verapamil, a patient with moderate hepatic impairment receiving the moderate CYP3A inhibitor diltiazem, and a patient with severe hepatic impairment receiving the CYP3A inducer carbamazepine. The day 1 and day 8 dose-normalized AUC0-tlast values in these patients were generally close to the median values for their respective hepatic function groups, indicating that these concomitant medications are unlikely to have resulted in a meaningful bias in estimation of the effect of hepatic impairment on bortezomib exposure.

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamic data on 20S proteasome inhibition in blood showed that across dose levels and hepatic function groups, the maximum mean percent inhibition of blood 20S proteasome activity occurred at the first post-dose time point of 1 hour, with a partial reversal to baseline observed by 24 hours post dose. In the normal hepatic function group, maximum mean percent inhibition of 20S proteasome activity on days 1 and 8 was approximately 43% and 73%, respectively. At 24 hours post dose, corresponding mean percent inhibition values were approximately 31% and 40%, respectively. Mean pharmacodynamic time course profiles at doses of 1.3 mg/m2 in the mild impairment group and 0.7 and 1.0 mg/m2 in the moderate and severe impairment groups were similar to those in patients with normal hepatic function. The magnitude of percent inhibition of blood 20S proteasome activity following treatment at 0.5 mg/m2 in patients with severe hepatic impairment was lower than that observed at the higher dose levels (data not shown).

Efficacy

One patient in the normal hepatic function group with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (small lymphocytic lymphoma) achieved a minor response, and five patients achieved stable disease, one in the normal function group with head and neck cancer, one in the mild impairment group (1.3 mg/m2) with colorectal cancer, two in the moderate impairment group (both 0.7 mg/m2) with pancreatic cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, and one in the severe impairment group (1.0 mg/m2) with sarcoma. Among the remaining patients, 35 had progressive disease as their best response, and 20 were not assessable for response.

DISCUSSION

This pharmacokinetic study of bortezomib in patients with varying degrees of hepatic impairment has shown that the systemic exposure of bortezomib (dose-normalized AUC) is increased by approximately 60% in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment. By contrast, exposure is not increased in patients with mild hepatic impairment compared with those with normal liver function. The disposition kinetics observed in this study were consistent with those reported in other studies of bortezomib pharmacokinetics in multiple myeloma, with observation of multi-exponential decline in plasma concentrations post-dose and accumulation following twice-weekly repeat dose administration (12,19). It is of interest that moderate and severe hepatic impairment, as defined based upon total bilirubin >1.5–3.0 and >3.0 x ULN, respectively, in this study, resulted in similar magnitudes of increase in dose-normalized bortezomib exposure. As noted previously, CYP3A4 is one of the primary CYP enzymes involved in bortezomib metabolism (4,6-8), with co-administration of the strong CYP3A inhibitor ketoconazole producing, on average, a 35% increase in bortezomib systemic exposure (9). A previous study of CYP3A activity in cancer patients using the erythromycin breath test demonstrated that the activity of this enzyme is characterized by substantial variability, with elevation of liver function tests representing a statistically significant covariate (20). Specifically, moderate and severe hepatic impairment were associated with ∼50% reduction in CYP3A activity (20), although the hepatic impairment categories were not the same as the NCI Organ Dysfunction Working Group framework (13-15) used in the present study. Nevertheless, the observation of increased bortezomib exposure in moderate and severe hepatic impairment is consistent with decreased hepatic metabolism of bortezomib in patients with total bilirubin >1.5 x ULN.

The pharmacokinetic findings from this study support the following recommendations for bortezomib dosing in patients with varying grades of hepatic impairment. Patients with mild hepatic impairment do not require a starting dose adjustment and should be treated with the 1.3 mg/m2 recommended dose of bortezomib. In patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment, a dose of approximately 0.8 mg/m2 would be calculated to provide exposures that match the exposures at 1.3 mg/m2 in patients with normal hepatic function (i.e. calculated as 1.3 mg/m2 divided by the 1.6-fold observed mean increase in dose-normalized AUC relative to the normal hepatic function group). Based on these results, it is recommended that patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment should be started at a reduced dose of 0.7 mg/m2 during the first cycle, and a subsequent dose escalation to 1.0 mg/m2 or further dose reduction to 0.5 mg/m2 may be considered based on patient tolerance.

These data have resulted in an update to the US Prescribing Information, and have produced clear guidance on appropriate dosing of bortezomib in patients with varying grades of hepatic impairment to provide similar exposures to the standard dose in patients with normal liver function. This and other studies (13,14) demonstrate the value of NCI ODWG studies for determining the impact of liver dysfunction on the safety and pharmacokinetics of anti-cancer agents, and for recommending dosing adjustments in this patient population if required to ensure optimal therapeutic use.

Consistent with the pharmacokinetic results, the profile of 20S proteasome inhibition in blood following dosing at 1.3 mg/m2 in patients with mild hepatic impairment was comparable to the corresponding profile in patients with normal hepatic function. In patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment, the magnitude of the pharmacodynamic effect in blood with doses of 0.7 and 1.0 mg/m2 was generally similar to that observed with the 1.3 mg/m2 dose in patients with normal hepatic function.

Our safety findings suggest that the increasing degree of hepatic impairment did not appear to substantially increase toxicity at the dose levels studied in the respective hepatic function groups. The elevated rates of grade ≥3 and grade ≥4 AEs and serious AEs in patients with hepatic impairment, in the context of the rates in those with normal hepatic function, were consistent with the patients with hepatic impairment having associated co-morbidity. Our safety findings support the use of 0.7 mg/m2 as a starting dose in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment, with this dose appearing similarly well tolerated as the standard dose of 1.3 mg/m2 in patients with normal liver function. However, the number of patients within each subgroup was small (n=3–11), limiting the interpretation of the incidence of AEs.

Disease progression was the most common cause of study discontinuation and treatment-emergent death. The patients enrolled in this study predominantly had solid tumors, in which bortezomib has limited activity (21-26). However, in hematologic malignancies, in which bortezomib has substantial activity (27-33), hepatic impairment is rare (34-36). This adversely impacted overall study accrual. Indeed, in general accrual to such organ dysfunction studies may be compromised if the specific organ dysfunction being studied is not a common clinical feature of the disease areas for which a particular agent is indicated or has demonstrated notable activity. Nevertheless, our findings are clinically applicable in multiple myeloma and lymphoma, in which hepatic involvement is seen in some cases, resulting in abnormal function (34-37).

In conclusion, the increased systemic exposure of bortezomib in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment is consistent with hepatic metabolism being the primary clearance mechanism for this drug (5,7-9). The findings of this study have resulted in the development of appropriate guidelines for bortezomib dosing in this patient population (5).

Statement of Translational Relevance.

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib undergoes oxidative hepatic metabolism, and as such, its pharmacokinetics may be altered in patients with hepatic impairment. Although pharmacokinetic studies have been performed in patients with multiple myeloma, studies had not been undertaken specifically in patients with hepatic impairment, which are required for the development of scientifically informed dosing guidelines in these special populations. This study by the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group shows that the systemic exposure of bortezomib is increased by approximately 60% in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment, but not increased in patients with mild impairment, compared with those with normal liver function. These findings support recommendations for a reduced starting dose of bortezomib in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment, and have resulted in an update to the United States Prescribing Information, which now includes guidelines on appropriate dosing in patients with varying grades of hepatic impairment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the patients and their caregivers for their participation in this study. The authors would like to acknowledge Michael Bargfrede for his contributions to co-ordination of bortezomib bioanalyses and bioanalytical data management. The authors would also like to acknowledge the writing assistance of Steve Hill and Sunethra Wimalasundera of FireKite during the development of this publication, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Janssen Global Services.

Grant information:

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants No.s: U01-CA062487 (Karmanos Cancer Institute); U01-CA099168 (University of Pittsburgh); U01-CA70095 (Johns Hopkins University); U01-CA069853 (Cancer Therapy and Research Center at University of Texas Health Science Center); U01-CA062505 (City of Hope); U01-C 062491 (University of Wisconsin Paul P Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center).

Also supported by: the Institute for Drug Development, Cancer Therapy and Research Center at University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio: Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA054174; Johns Hopkins University Cancer Center Core Grant Support P30 CA006973.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

PML is a consultant for Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

KV, RN and D-LE are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

MAR is a consultant for Concordia Pharmaceuticals/Averion International Corp.

CHT is an employee of Johnson & Johnson, Ortho Biotech Oncology R&D.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Adams J, Kauffman M. Development of the proteasome inhibitor Velcade (Bortezomib) Cancer Invest. 2004;22:304–11. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams J. The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:417–21. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boccadoro M, Morgan G, Cavenagh J. Preclinical evaluation of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in cancer therapy. Cancer Cell International. 2005;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc. Prescribing information. Cambridge, MA, USA: 2011. VELCADE® (bortezomib) for Injection. Issued November, Rev 12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen-Cilag International N.V. Summary of Product Characteristics. Beerse, Belgium: 2009. VELCADE® (bortezomib) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labutti J, Parsons I, Huang R, Miwa G, Gan LS, Daniels JS. Oxidative deboronation of the peptide boronic acid proteasome inhibitor bortezomib: contributions from reactive oxygen species in this novel cytochrome P450 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:539–46. doi: 10.1021/tx050313d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pekol T, Daniels JS, Labutti J, Parsons I, Nix D, Baronas E, et al. Human metabolism of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib: identification of circulating metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:771–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uttamsingh V, Lu C, Miwa G, Gan LS. Relative contributions of the five major human cytochromes P450, 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4, to the hepatic metabolism of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1723–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkatakrishnan K, Rader M, Ramanathan RK, Ramalingam S, Chen E, Riordan W, et al. Effect of the CYP3A inhibitor ketoconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors: a prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized, two-way crossover drug-drug interaction study. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2444–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn DI, Nemunaitis J, Fuloria J, Britten CD, Gabrail N, Yee L, et al. Effect of the cytochrome P450 2C19 inhibitor omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumours, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:199–209. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leal TB, Remick SC, Takimoto CH, Ramanathan RK, Davies A, Egorin MJ, et al. Dose-escalating and pharmacological study of bortezomib in adult cancer patients with impaired renal function: a National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group Study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1637-5. e-pub ahead of print, Apr 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reece DE, Sullivan D, Lonial S, Mohrbacher AF, Chatta G, Shustik C, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of two doses of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramalingam SS, Kummar S, Sarantopoulos J, Shibata S, Lorusso P, Yerk M, et al. Phase I study of vorinostat in patients with advanced solid tumors and hepatic dysfunction: a National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4507–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanathan RK, Egorin MJ, Takimoto CH, Remick SC, Doroshow JH, LoRusso PA, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of imatinib mesylate in patients with advanced malignancies and varying degrees of liver dysfunction: a study by the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:563–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Synold TW, Takimoto CH, Doroshow JH, Gandara D, Mani S, Remick SC, et al. Dose-escalating and pharmacologic study of oxaliplatin in adult cancer patients with impaired hepatic function: a National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group study. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3660–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lightcap ES, McCormack TA, Pien CS, Chau V, Adams J, Elliott PJ. Proteasome inhibition measurements: clinical application. Clin Chem. 2000;46:673–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau P, Coiteux V, Hulin C, Leleu X, van d V, Acharya M, et al. Prospective comparison of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2008;93:1908–11. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker SD, van Schaik RH, Rivory LP, Ten Tije AJ, Dinh K, Graveland WJ, et al. Factors affecting cytochrome P-450 3A activity in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8341–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberts SR, Foster NR, Morton RF, Kugler J, Schaefer P, Wiesenfeld M, et al. PS-341 and gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1654–61. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel RH, Brown JA, Von Roenn JH, O'Regan RM, Bergan R, Badve S, et al. A phase II study of single agent bortezomib in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a single institution experience. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:733–7. doi: 10.1080/07357900701506573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanucchi MP, Fossella FV, Belt R, Natale R, Fidias P, Carbone DP, et al. Randomized phase II study of bortezomib alone and bortezomib in combination with docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5025–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegewisch-Becker S, Sterneck M, Schubert U, Rogiers X, Guerciolini R, Pierce JE, et al. Phase I/II trial of bortezomib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4089. (abstract 4089) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lara PN, Jr, Chansky K, Davies AM, Franklin WA, Gumerlock PH, Guaglianone PP, et al. Bortezomib (PS-341) in relapsed or refractory extensive stage small cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group phase II trial (S0327) J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:996–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackay H, Hedley D, Major P, Townsley C, Mackenzie M, Vincent M, et al. A phase II trial with pharmacodynamic endpoints of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5526–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Bella N, Taetle R, Kolibaba K, Boyd T, Raju R, Barrera D, et al. Results of a phase 2 study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115:475–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-233155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, Djulbegovic B, Robertson MJ, de VS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4867–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reece DE, Sanchorawala V, Hegenbart U, Merlini G, Palladini G, Fermand JP, et al. Weekly and twice-weekly bortezomib in patients with systemic AL amyloidosis: results of a phase 1 dose-escalation study. Blood. 2009;114:1489–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2487–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson PG, Mitsiades C, Schlossman R, Ghobrial I, Hideshima T, Munshi N, et al. Bortezomib in the front-line treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:1053–72. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:906–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treon SP, Hunter ZR, Matous J, Joyce RM, Mannion B, Advani R, et al. Multicenter clinical trial of bortezomib in relapsed/refractory Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia: results of WMCTG Trial 03-248. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3320–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhandari MS, Mazumder A, Vesole DH. Liver involvement in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007;7:538–40. doi: 10.3816/clm.2007.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahhal FE, Schade RR, Nayak A, Coleman TA. Hepatic failure caused by plasma cell infiltration in multiple myeloma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2038–40. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomyo H, Kagami Y, Kato H, Kawase T, Ohshiro A, Oyama T, et al. Primary hepatic follicular lymphoma : a case report and discussion of chemotherapy and favorable outcomes. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2007;47:73–7. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.47.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai R, Medeiros LJ. Pathologic diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2000;1:197–206. doi: 10.3816/clm.2000.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]